An Extraordinary Journey: FOSIL (Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning)

Home › Forums › FOSIL Presentations › An Extraordinary Journey: FOSIL (Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning)

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 5 years, 5 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

28th August 2020 at 4:20 pm #14380

Although not a conventional presentation, this interview with Darryl Toerien, originally published by Elizabeth Hutchinson on her website, provided a sustained opportunity to reflect on the development of FOSIL over the last 10 years.

—

I was lucky to meet Darryl Toerien way back in 2011 when I was beginning to understand the importance of information literacy within the curriculum. He was the first person I spoke to who had the same excitement about this topic that I had. I listened to him speak and I got excited by his deep passion for school libraries and the difference they can make to a student’s education.

However, we are like chalk and cheese, he is a really deep thinker and does not throw words away unnecessarily whereas I am completely the opposite. I enjoy the quick game and get little pleasure in taking years over an idea. If I have an idea I want to do something now, very often trying to work it out as I go along which sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. We work well together as he pushes me to be my best self by being more thoughtful, and I hope that what I bring is the exposure and simpler voice that his ideas deserve.

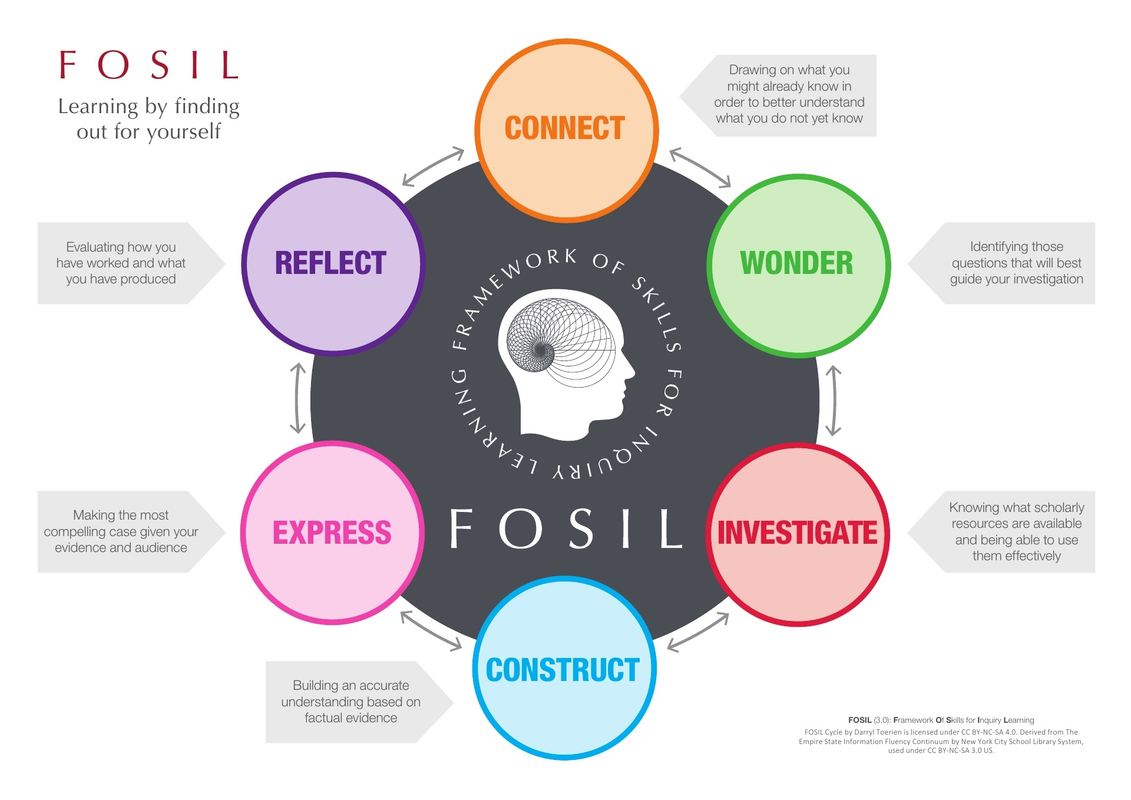

I first heard that he had broadened his thinking beyond Information Literacy in around 2013 when he contacted me to ask if I was interested in looking at FOSIL which at the time was Framework for Oakham School Information Literacy, which in his words made the school library and librarian integral to the curriculum and gave students the opportunity to find out about and make sense of the world by finding out for themselves; with appropriate help of course. I renamed it as CWICER, Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express and Reflect. This framework allowed school librarians to demonstrate to teachers where their skill set fits into the curriculum and for school librarians to recognise where information literacy fits within that too.

In 2015, he renamed FOSIL to Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning which meant that anyone could use FOSIL exactly as it was created. Having now worked with FOSIL for over five years and can honestly say that I am still enjoying learning how school librarians and teachers can work with it. It is not about a rule book but an open opportunity to help school librarians and teachers move forward together in a way that supports their students and within their own environment.

The biggest thing for me is that I now feel that I have something that is solid and of value to give to school librarians. Something that is being recognised beyond The FOSIL Group, the website he set up to share best practice, as far away as Australia and America. He is totally committed and the amount of time he has put into this is astronomical and for no financial gain. He truly believes in giving and sharing to make our society better. Darryl has spent years getting this right and it is still evolving and I wanted to give him the opportunity to talk about this journey in his own words.

—

Let me start by thanking you for this opportunity to pull my thoughts together, and not just about FOSIL, because FOSIL, it turns out, is what I think about school libraries, schools and education.

Question 1: What is the background to FOSIL?

FOSIL is the result of trying to solve two specific problems within the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Programme (DP) relating to the Extended Essay (EE), a mandatory independent, self-directed piece of research, finishing with a 4,000-word paper.

Firstly, how to effectively prepare our students for the demands of the EE, specifically how to accurately cite and reference according to a standard style, when, for the majority of them, their education at school up to that point would not have required work of this nature. This led me to what I thought was a framework of information literacy skills, but, serendipitously, turned out to be a framework/ continuum of inquiry skills and accompanying framework/ model of the inquiry process (the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, or ESIFC, which was developed by the School Library Systems Association of New York State under the leadership of Barbara Stripling), which led directly to FOSIL and is what FOSIL is based on. According to the ESIFC, which was then in use in schools throughout New York City, citing and referencing was a priority benchmark skill in Grade 5/ Year 6 (Cites all sources used according to model provided by teacher), Grade 7/ Year 8 (Cites all sources used according to local style formats, which I took to mean a house style) and Grade 10/ Year 11 (Cites all sources used according to standard style formats). The immediate consequence of this was deciding on APA as our standard style format as well as our house style, which we teach from Year 6 through to Year 13.

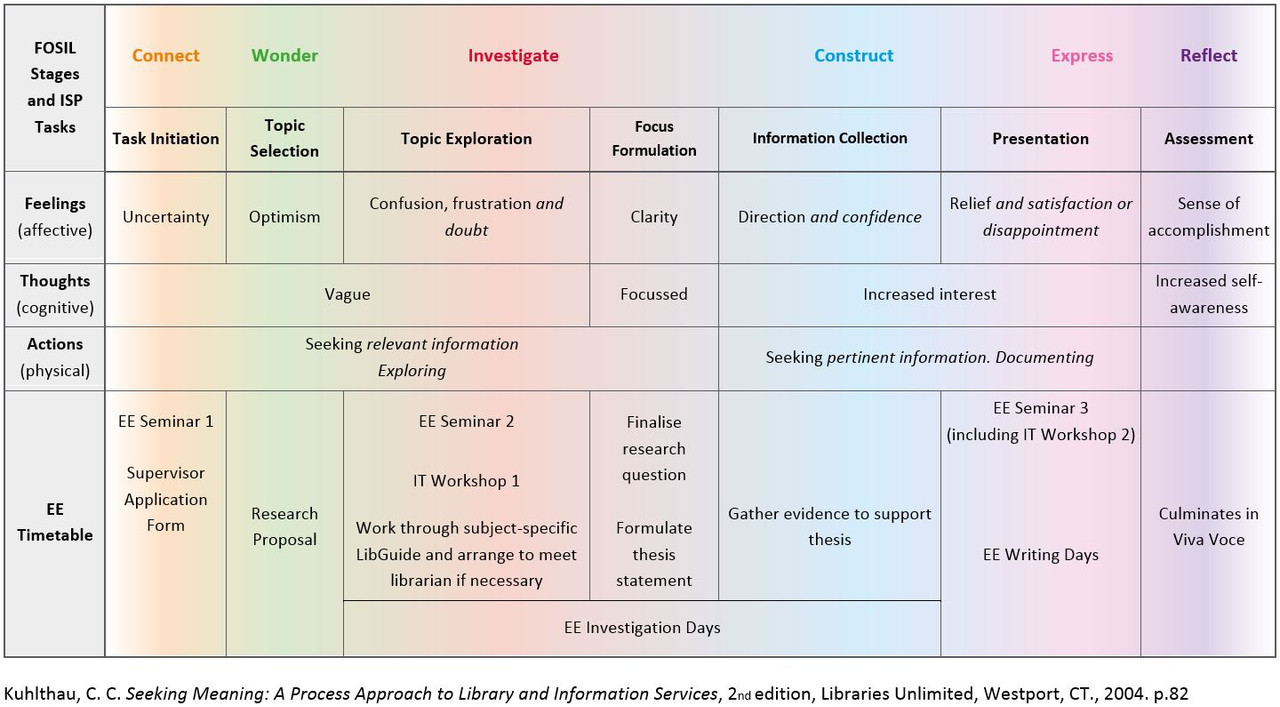

Secondly, how to more effectively support the EE out of a deeper understanding of the inquiry process. This was motivated by a sense that our EE timetable, which in many respects was exemplary, worked against the inquiry process at certain key points because it driven primarily by administrative concerns. The clearest example of this was the requirement for a research question to start the process rather than allowing the research question to emerge from the process. This led me to Carol Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process (ISP), which not only added an affective, cognitive and physical dimension to our understanding of the inquiry process, which not only allowed us to realign our EE timetable to reinforce the inquiry process, but also identified points of optimal intervention in support of the EE process (see below, which also reflects our current alignment of our EE timetable with our growing understanding of Kuhlthau’s ISP and the ESIFC/ FOSIL).

It must be noted that we are not combining the ESIFC/ FOSIL with Kuhlthau’s ISP, only that we are trying to respectfully combine insights that we are gaining into the inquiry process from two highly regarded bodies of work, for which we are very grateful.

Question 2: Why did you decide that an Information Literacy Framework was not enough for your own needs?

As I touched on in my answer to your first question, I started out by looking for a concrete progression of what I considered to be information literacy skills, specifically citing and referencing. After all, if we were expecting Year 12 students doing the IB Diploma Programme to cite and reference according to a standard style, such as APA or MLA, and they couldn’t do so confidently and competently, and we couldn’t in good conscience say that we had taught them how to do so and given them meaningful opportunities to practice doing so in all of their subjects in their years leading up to this point, then this was profoundly unfair to them and the fault lay with us. What further troubled me was that many of my colleagues in other academic departments at the time considered citing and referencing to be a technical skill that students would be taught at university, even though we were already requiring them to do so for the Extended Essay. Now while there is a technical element to citing and referencing, this seemed to me to be an academic skill – we cite and reference because we are working with other people’s ideas as expressed through their work – and that this academic skill needed to be practiced in all academic disciplines and in increasingly sophisticated ways if it was to be mastered.

This was a crucial moment for me, even though I did not fully recognize it at the time.

Firstly, and although I instinctively knew it, I realized that my real concern was not how to teach citing and referencing, or information literacy skills more broadly, but how to collaborate with my teaching colleagues from other academic disciplines on creating meaningful opportunities for students to learn how to cite and reference in the process of learning about the content, or subject matter, of those disciplines. What this amounts to is finding ways to work with subject teachers to teach their subject in a way that requires students to learn in a way that requires them to learn something about the subject for themselves, with appropriate help, and in the process acknowledge the sources of information that they learn from. So, my focus is not citing and referencing, or information literacy more broadly, but learning, and specifically the process of learning from information. This process of learning from information would turn out to be inquiry.

Secondly, and again instinctively, this process of learning for oneself from information seemed to both require independent learning and develop independent learning, which was a topical concern at that time. My reading into independent learning confirmed two things: (1) independent learning is a complex process that makes cognitive, metacognitive and affective demands on students, and; (2) students do not become effective independent learners without being taught the skills required to become effective independent learners, and without being given opportunities to practice and develop those skills, with appropriate interventions, progressively and systematically within the curriculum. The literature on independent learning revealed an interesting and fruitful overlap with Kuhlthau’s work on the ISP – which would eventually develop into Guided Inquiry Design – in terms of the affective, cognitive and physical dimensions of learning from information, and inquiry more broadly (see the image in my answer to your first question).

Therefore, having set out to find a framework information literacy skills, and having stumbled into a framework/ model of the inquiry process along with a framework/ continuum of inquiry and related skills, I found myself increasingly turning my attention to the inquiry process as an approach to learning, and teaching for learning.

Barbara Stripling (2017) accurately describes the situation that I found myself in: “Providing a framework of the inquiry process is only the first step in empowering students to pursue inquiry on their own. The next step is to structure teaching around a framework of the literacy, inquiry, critical thinking, and technology skills that students must develop at each phase of inquiry over their years of school and in the context of content area learning” (p. 52).

Interestingly, having been a teacher, and being scholarly by nature, I realized that I had always approached learning, and teaching for learning, through the process of inquiry even though I lacked a model of the inquiry process and associated vocabulary. The reason for this became clear to me when I came across the following description of inquiry on the Galileo Educational Network website: “Inquiry is a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world, and as such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created.” Understood in this way, inquiry is a natural way to learn, and this can be more or less actively encouraged and effectively supported by teachers. Furthermore, as a child, and later as a student and then a teacher, the library was my intellectual and academic home. Later, having found myself as a school librarian, I came to understand that the spirit of inquiry gave birth to the library and that the library is home to the spirit of inquiry even if it is not always welcome in the library, and especially in the school library. Yet, as Daniel Callison (2006) points out, “the school library only exists as a learning centre because of inquiry” (p. 601), and this is what I had been striving towards in the library without fully realizing it since serendipitously finding my way into school librarianship in 2003.

Question 3: Explain why you chose to focus on something evolving in America – the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (ESIFC) – and not something closer to home?

As you well know, a professional qualification, even a CILIP-accredited one, in this country does not teach you anything specific about school librarianship. I still need to investigate the reasons for this, but this is in stark contrast to many other countries where it is possible to specialize in school librarianship. In these countries – countries that recognize that the most critical condition for an effective pedagogical program, without which the school library is not able to fulfil its educational purpose, is a “[professionally] qualified school librarian with formal education in school librarianship and classroom teaching” (IFLA School Libraries Section, 2015, pp. 17-18) – inquiry has long been considered to be a core activity of the library’s pedagogical program if the library is actually to be “essential to the educational process” as expressed in the IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto (1999), and reaffirmed in the IFLA/UNESCO School Library Guidelines (2002) and the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015). Many of these countries have, over many years, “worked out very successful models for designing instruction that develops media and information literacy skills within the context of inquiry” (IFLA School Libraries Section, 2015, p. 41). Two of the most influential of these models are Kuhlthau’s ISP/ Guided Inquiry Design and Stripling’s Cycle of Inquiry/ ESIFC/ FOSIL. It is unsurprising, then, that a search for an information literacy skills framework should lead to the work of Kuhlthau and Stripling.

The three main reasons for choosing Stripling’s Cycle of Inquiry/ ESIFC were:

- The highly detailed and clearly thought out framework of the “literacy, inquiry, critical thinking, and technology skills that students must develop at each phase of inquiry over their years of school and in the context of content area learning” that enables the inquiry process (see here for the 2009 FOSIL continuum – I am still in the process of updating this to reflect the reimagined 2019 ESIFC continuum, although the 2019 ESIFC continuum of skills can be found here).

- The six phases, or stages, of Stripling’s Cycle of Inquiry – Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express, Reflect – make logical sense and are therefore easy to remember.

- Both the Cycle of Inquiry and the underlying continuum of skills as expressed in the ESIFC are available under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license, without which it would not have been possible for us to develop and share FOSIL, which is on ongoing effort to respectfully transplant the ESIFC in foreign soil. I am delighted to say that this effort, which stretches back to 2012, has received an original maker’s mark, with FOSIL being reciprocally endorsed by the School Library Systems Association of New York State in April 2020 and Barbara Stripling commending the FOSIL Group website, which was formed in April 2019 to support ongoing development and increasingly widespread use of FOSIL, for its “clear and elegant presentation of inquiry.”

However, having found in Kuhlthau’s ISP a powerful tool for solving a different set of problems it would have made no sense to abandon the ISP, which is where our work on respectfully combining the insights of the ISP with FOSIL began. I am now at point where I feel confident enough to reach out to Carol Kuhlthau to thank her in person for her work leading to the ISP, and for the value that this has added to our work on FOSIL.

To address your question more directly, I clearly remember that at the outset of my journey that would eventually lead to FOSIL that I looked with great hope to promising developments closer to home in both Scotland and Wales. Unfortunately work on the National Information Literacy Framework [for] Scotland, which began in October of 2004, was suspended in 2013, and it is practically impossible to figure out what eventually happened to the Information Literacy Framework for Wales, which was published in 2011 and initiated in 2009. By contrast, both Kuhlthau’s ISP leading to Guided Inquiry Design and Stripling’s REACTS Taxonomy leading to the Cycle of Inquiry/ ESIFC stretch back to 1988, and are still as vital and influential today as they were when they were first being developed.

Question 4: Why did you choose to create FOSIL instead of using Barbara Stripling’s model of inquiry, which the ESIFC is based on?

FOSIL started out as a relatively modest undertaking, which was simply as a Framework for Oakham School Information Literacy – that is, a framework of information literacy skills, and the ESIFC’s Creative Commons licence allowed us to do that. However, it soon became clear that a growing number of colleagues at other schools – librarians, teachers, senior leaders – were on a similar journey, and that interest in FOSIL was far more widespread than Oakham School. This interest in FOSIL beyond Oakham School, combined with the fact that what we were actually developing was a framework of the inquiry process and associated skills rather than a framework of information literacy skills, afforded us the opportunity to more accurately reflect what FOSIL was in its name, and, happily, Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning turned out to be exactly what FOSIL had been all along!

This had the added benefit that colleagues elsewhere could adopt/ adapt FOSIL without needing to rename it. The history of FOSIL in Guernsey is a case in point, when you successfully transplanted it in 2013 as CWICER – Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express, Reflect – following our serendipitous meeting in 2011. A similar thing happened in 2015 with Alison Tarrant, now Chief Executive of the School Library Association but then Librarian at Cambourne Village College, where FOSIL ‘became’ Stripling’s Model. While you and Alison, and you are just two examples, had done exactly what I had done, it became clear to me very quickly, then, that we actually needed to be constructing a shared vocabulary around inquiry, because, as Deborah Levitov (2016, p. 30) warns, standardisation of inquiry language is an important step if all educators are to share a common understanding, and without which effective collaboration between librarians and teachers is simply not possible. Oakham School’s extraordinarily far-sighted decision to rename FOSIL, as well as its significant and substantial contribution to the formation of the FOSIL Group, must be noted in the historical record, because without these the rapid expansion of FOSIL beyond Oakham School, as reflected in the FOSIL Group, would not have been possible, and this, in my opinion, is an act of visionary and selfless leadership. Subsequent developments in Guernsey serve to illustrate this, with your bold and equally far-sighted decision to then rename CWICER as FOSIL, and the extent to which this then both enabled more effective collaboration between librarians and teachers in Guernsey, while also broadening that collaboration through the FOSIL Group to include librarians and teachers from beyond Guernsey.

Question 5: Why do you think it is important for school librarians to have a framework? Do they really need one?

The IFLA School Library Guidelines (IFLA School Libraries Section, 2015), drawing on almost 60 years of international research, make it clear that without a pedagogical program – a planned, comprehensive offering of teaching and learning activities – even a professionally qualified librarian with a school library specialization will not be able fulfil the library’s educational purpose. Now while the library’s moral purpose – making a difference in the lives of young people – is equally important, it is the library’s educational purpose that forms the frontline of the battle for the continued existence of school libraries. Of the 5 instructional activities that the Guidelines list – literacy and reading promotion; media and information literacy [MIL] instruction; inquiry-based teaching and learning, which includes MIL instruction; technology integration; professional development for teachers – inquiry-based teaching and learning will become ever more critical to the success of the library’s pedagogical program, on which the library’s future depends. As should be clear from my answers to your previous questions, without a shared framework of the inquiry process, which is actually a learning/ educational process, and underlying framework of inquiry and related skills, librarians will lack the means to collaborate effectively with teachers, which is necessary if they are to make the library essential to the educational process, and so fulfil the library’s educational purpose.

So yes, I am firmly convinced that they need one.

Question 6: There are several other frameworks currently out there. If a school librarian is using something else can they still join in this conversation about inquiry learning?

Absolutely.

As I have said before, inquiry is an approach to learning. Having said that, inquiry is also a complex process. As Daniel Callison (2015, p. vii) points out, there has been an evolution towards inquiry as well as of inquiry learning since the 1960s and many talented colleagues have contributed to this ongoing evolution in both of these senses. Over this time, some frameworks/ models have disappeared into the historical record, while others have grown in their influence at building level and/ or district level and/ or national, and even international, level. None of these frameworks exists, or was developed, in isolation, though, and FOSIL is a case in point. While it is based on the ESIFC/ Stripling’s Cycle of Inquiry, it is also influenced by Kuhlthau’s ISP/ Guided Inquiry Design, and countless other sources. The reason for this is that there is an underlying logic to the inquiry process, and it this logic that concerns us. So, up to a point the choice of how to frame the process is a matter of preference based on any number of considerations. However, beyond a certain point, the IFLA Guidelines (IFLA School Libraries Section, 2015, pp. 41-43) include the following caution:

Creating models for inquiry-based learning involves years of research, development, and practical experimentation. Schools without a model recommended by their education authority should select a model that aligns most closely with the goals and learning outcomes of their curricula, rather than attempting to develop their own models. … Where there is no locally or nationally developed model for inquiry-based teaching and learning, a school librarian should work with the classroom teachers and school leaders to select a model. As the teachers and students apply the model they may wish to adapt the model to serve school goals and local needs. However, caution should be exercised in adapting any model. Without a deep understanding of the theoretical foundations of the model, adaptations may eliminate the power of the model.

Provided, then, that the chosen framework is theoretically sound, it doesn’t matter which framework someone is using for joining this discussion to be mutually beneficial. And even if the framework in question is not theoretically sound, joining this conversation might be an important step towards that, which will be of immense value to teaching colleagues and students.

Question 7: How important is the collaboration between teachers and school librarians in this framework? Can it be used without one or the other?

Because inquiry is an approach to learning, or a learning process, and FOSIL frames this process in terms of stages and skills, FOSIL would be useful to any teacher who approached learning, and teaching, through inquiry. This is the same for librarians, although more so, because I do not think that is possible to separate the school library from learning, and specifically learning through inquiry, whether formal or informal. Therefore, FOSIL, or an equivalent, is necessary if librarians are to contribute more fully to learning and teaching in the school.

However, as I hope has become increasingly clear, inquiry is a complex process that requires purposeful instruction and effective support over all of their years and across all of their subjects if our children are to emerge from school well equipped for learning for themselves beyond school. This is not possible for teachers or librarians to do on their own, because teachers and librarians are both specialists and each contributes specialist knowledge and expertise that the other does not have. So FOSIL, in framing the inquiry process and skills, both facilitates this collaboration between teachers and librarians, but also encourages, and ultimately necessitates, it. And this, again, is the purpose and growing value of the FOSIL Group, which is to facilitate, encourage and extend this collaboration as widely as possible for the benefit of our children.

Question 8: Why did you decide to make FOSIL freely available?

Two reasons.

Firstly, the Creative Commons licence that the EFIFC is made available under stipulates that:

- You are free to:

- Share— copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt— remix, transform, and build upon the material

- Under the following terms:

- Attribution— You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- NonCommercial— You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

- ShareAlike— If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.

Secondly, and more importantly to me, is the fact that I spent many years, mostly alone, on a brutally steep learning curve, and while this no doubt ultimately contributed to a deeper understanding of what I was/ am doing, it also cost me time, energy and vital earlier opportunities to make the library essential to the educational process. Consequently, I will do anything that is in my power to do that might help colleagues cover the same ground more quickly, because the hour for school libraries is late.

Question 9: Where do you see FOSIL in the future of school librarianship?

FOSIL started simply as an attempt to help students with their Extended Essay. However, the Extended Essay is also an approach to learning, specifically through inquiry, that runs through the entire IB continuum of education – Primary Years Programme, Middle Years Programme, Diploma Programme and Career-related Programme. Inquiry, as an approach to learning, is also fundamental to the educational process at a national level in a number of countries. So, what started out with a very narrow educational focus very quickly broadened out into a concern with the educational process as a whole, and one that is absolutely not limited to the IB continuum. It also became clear very quickly that this broader concern was shared by a growing number of colleagues from within and beyond Oakham School. I was aware, therefore, almost from the outset, that FOSIL had value well beyond Oakham School.

Given that FOSIL took recognizable shape in 2012, at around the same time as the National Information Literacy Framework [for] Scotland and the Information Literacy Framework for Wales, and given that FOSIL was rooted in Stripling’s ESIFC and Kuhlthau’s ISP, it occurred to me that FOSIL might serve to bootstrap a national framework for England. This was the question that I eventually posed at the SLG National Conference in April of 2018, before going to form the FOSIL Group in April of 2019 – with the support of Oakham School and the blessing of CILIP SLG, CILIP ILG and SLA – in order to more effectively support the growing number of colleagues in other schools who were adopting FOSIL. Noteworthy FOSIL-related achievements since then include:

- Being shortlisted for the CILIP ILG Information Literacy Award in 2019 and the Digital Award for Information Literacy 2020

- Being shortlisted for the Strategic Educational Initiative of the Year Award in the Times Educational Supplement Independent School Awards 2020

- Being endorsed by the Great School Libraries campaign as its recommended model of the inquiry process in 2020

- The reciprocal endorsement by the School Library Systems Administration of New York State in 2020

- Featuring in my keynote address at the International Association of School Librarianship Conference in Dubrovnik in 2019

- Featuring in my paper – (Re)Discovering Inquiry In and Through the School Library: the FOSIL Model – at the IFLA Mid-year Conference in Rome in 2020 (pending imminent publication)

- Featuring in my article – (Re)Purposing the School Library – for Mediadoc, the professional Journal of A.P.D.E.N., the National Federation of French professeurs documentalistes (pending imminent publication)

Whether FOSIL or not, I am firmly convinced that a national framework of the inquiry process, along with a framework of “the literacy, inquiry, critical thinking, and technology skills that students must develop at each phase of inquiry over their years of school and in the context of content area learning,” is necessary for librarians to position their libraries as essential to the educational process, and in so doing fulfil the school library’s educational purpose.

If FOSIL proves to have been a helpful step in this direction, that will be enough.

Question 10: If you were able to start again from scratch, what might you do differently?

I have often thought about this, so the answer to this question is easy.

Firstly, I would not have wasted time and money on a professional qualification at a university in the UK, because I learned nothing of specific relevance to school librarianship. How we came to find ourselves in this debilitating situation deserves investigation, because, as I mentioned earlier, a professionally qualified school librarian with formal education in school librarianship and classroom teaching is the most critical condition for an effective pedagogical program, without which the school library is not able to fulfil its educational purpose (IFLA School Libraries Section, 2015, pp. 17-18). How we go about achieving this is a huge and daunting task, and one that will take many people working together over a number of generations, and the only thing that will sustain us is that our children, and their children, and their children’s children are worth it.

Secondly, and related to the first, I would have fully embraced my ignorance and contacted Barbara Stripling and Carol Kuhlthau immediately and directly, and then enrolled for a professional qualification with a school library specialization at either Syracuse University, which was where Barbara Stripling was, or Rutgers University, which was where Carol Kuhlthau was. This may have been more costly in the short term, but would have been immeasurably more valuable in the long term, and not only because I would have learned something of specific relevance to school librarianship – it would have drawn me into the community of colleagues who are bound for the same educational destination that I am, and this, as I have come to realise, and have attempted to achieve through the FOSIL Group, is at least valuable, if not more so.

Bibliography

Callison, D. (2015). The evolution of inquiry : controlled, guided, modeled, and free. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Callison, D., & Preddy, L. (2006). The blue book on information age inquiry, instruction and literacy. Westport: Libraries Unlimited.

IFLA School Libraries and Resource Centres Section. (1999). IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto. Retrieved from IFLA School Libraries Section: https://www.ifla.org/publications/ifla-unesco-school-library-manifesto-1999?og=52

IFLA School Libraries and Resource Centres Section. (2002). The IFLA/UNESCO School Library Guidelines. The Hague: IFLA.

IFLA School Libraries Section. (2015). IFLA School Library Guidelines. The Hague: IFLA.

Levitov, D. (2016). School Libraries, Librarians, and Inquiry Learning. Teacher Librarian, 28-35.

Stripling, B. (2017). Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment. In S. W. Alman (Ed.), School librarianship: past, present, and future (pp. 51-63). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.