A theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › A theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience

- This topic has 12 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 3 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

6th November 2020 at 8:05 pm #27713

A blog post for CILIP SLG’s Talking Books (5 November 2020).

—

I write this as I approach the end of my second spell on the National Committee of SLG. My first started shortly after I became a school librarian, by chance rather than design (or at least through no design of my own). This means that serving on the National Committee of SLG has framed pretty much the first 20 years of my work in and for school libraries, and that a measure of reflection is, therefore, appropriate.

An even earlier and profoundly formative experience was stumbling across Jesse Shera’s The Foundations of Education for Librarianship (1972) in a charity shop in Caversham. In this remarkable book, Shera articulated what I instinctively knew about librarianship in general, and school librarianship in particular. This may seem a little odd, given that he was writing partly about academic librarianship in the US in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Not so odd when you consider Blanche Woolls’ observation that the only difference between a school librarian and an academic librarian is, or ought to be, the length of time between a student leaving school and starting university, and that the fundamental issues confronting Shera then and there confront us still here and now. One passage in particular illustrates this, and set the course of my professional development (p. 177, emphasis added):

Increasingly, research as a method of instruction and an environment for formalized learning is being introduced into undergraduate as well as graduate programs.* This undergraduate research, or more properly, inquiry, has its own characteristic information needs, though academic librarians generally have given these requirements slight attention, while the faculty has tended to ignore them almost entirely. This neglect may doubtless be attributed to the fact that the instructors themselves were not properly encouraged in the use of the library in their own undergraduate years. The textbook and the reserve collection, which in the final analysis is only a kind of multiple text, have too long dominated undergraduate, and even graduate, instruction. The teacher’s own mimeographed reading lists and bibliographies have been imposed between the student and the total library collection, largely because the typical faculty member does not trust either the bibliographic mechanisms of the library or the competence of the librarians, while the librarians, for their part, have never developed a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience. This neglect has been intensified by the absence of any real communication between teacher and librarian, both have paid lip service to the library as a ‘learning center,’ and having said that satisfied their sense of obligation with a short course or a few lectures on ‘How to Use the Library.’

I have been wrestling with a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience ever since. Shera led me to Patricia Knapp (1966), who led me to Helen Sheehan (1969), who led me to Norman Beswick (1967), who posited that “it is not the library that ‘supports’ the classroom . . . but the classroom that leads (or should lead) inevitably and essentially to the library” (p. 201). It seemed to me then, as it does to me now, that a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience needs to compellingly account for why the classroom leads (or should lead) inevitably and essentially to the library, as well as how. Shera provided 2 clues – “inquiry” and the “library as a learning center” – in this passage. Daniel Callison (2006) linked them explicitly, stating that “the school library only exists as a learning centre because of inquiry” (p. 601). Inquiry, then, frames learning, and it is unsurprising, therefore, that the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015) define the school library in terms of inquiry (p. 16) – “a school’s physical and digital learning space where reading, inquiry, research, thinking, imagination, and creativity are central to students’ information-to-knowledge journey and to their personal, social, and cultural growth” – and include inquiry as one of the core instructional activities that make up the school library’s pedagogical program (pp. 41 – 44). This brings me to the present.

I was recently interviewed by Barbara Stripling for School Library Connection (a publication of Libraries Unlimited/ ABC-CLIO) about The Process and Stance of Inquiry in a Digital World. The title of the interview, and the starting point of our discussion, comes from the Galileo Educational Network’s definition of inquiry as a dynamic process and stance that is essential to the way in which knowledge is created. Inquiry is, therefore, an epistemological concern – a concern with what we know and how we come to know it – the “information-to-knowledge” part of the IFLA definition of a school library. As such, inquiry is a fundamental human activity, and the library is, or ought to be, essential to this activity. This, however, demands something of us as librarians, and of our libraries. Moreover, this process and stance is both facilitated by the digital world, and hindered by it, and Barbara was interested in my thoughts on this from the perspective of FOSIL, which is based on the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (2019) that she led the development of.

Somewhat paradoxically, the very characteristics of the digital environment that facilitate inquiry also hinder inquiry. The question of equality of access as aside for now, although it remains a pressing concern, these characteristics broadly relate to the quantity of information, discernment of its quality and motivation. At a certain point the relentless increase in the quantity of information brings about a qualitative change – scarcity of information becomes an abundance of information, which becomes a superabundance of information. The problem then shifts from finding enough information to dealing with too much information, which is both a different and a new problem. David Foster Wallace’s Total Noise captures this qualitative change perfectly – the growing “tsunami of available fact, context and perspective” (2007!). Then, to this tsunami must be added the growing maelstrom of mis-information, dis-information and mal-information created, manipulated and distributed to devastating effect. And to make matters worse, the difficulties of building knowledge and understanding from information in these conditions is made more challenging still by the fact that the digital environment is both overwhelming and endlessly distracting, and this brings us full circle – inquiry is both an epistemological process and stance, and being able to carry out the process is no guarantee that we will care enough, one way or another, to make the effort to do so.

Huw Davies (2019) issues the following stark warning:

No digital literacy programme is ever likely to work unless it produces reflexive critical thinkers, motivated to challenge their own thinking and positionality: people know and care when they are being sold a biased or racist view of history, pseudo-science or when they are being manipulated.

This highlights the importance of inquiry as stance, which, I think, must now become our focus and most urgent task. In this we draw on 60 years’ worth of work in and through the school library on inquiry as process, which, in the words of the IFLA School Library Guidelines unites us with our classroom colleagues in the aim of “influencing, orienting, and motivating the pursuit of learning using a process of discovery that encourages curiosity and a love of learning” (p. 43).

—

*This extends to schools. As Daniel Callison (2015) points out, “the progression to student-centered, inquiry-based learning through school library programs was clearly underway more than forty years ago” (p. 3), at least in the US, and can be traced back to 1960 (p. 213). More broadly, though, Callison lists the International Baccalaureate (IB) Program as an early adopter of inquiry (p. 214). The IB was founded in 1968, although the philosophy, structure, content and pedagogy of the IB Diploma Programme, which was the first IB Programme, were developed in 1962 (IBO, 2017). The Diploma Programme was followed by the Middle Years Programme, the Primary Years Programme and the Career-related Programme, with “inquiry, as a curriculum stance, pervading all Programmes” (Tilke, 2011, p. 5).

—

Bibliography

Beswick, N. W. (1967). The ‘Library-College’ – the ‘True University’? The Library Association Record, 198-202.

Callison, D. (2015). The Evolution of Inquiry: Controlled, Guided, Modeled, and Free. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Davies, H. (2019, June 14). Digital literacy vs the anti-human machine: A proxy debate for our times. Retrieved from Medium: https://medium.com/@huwcdavies/digital-literacy-vs-the-anti-human-machine-b2884a0f075c

IBO. (2017). The history of the IB. Retrieved from International Baccalaureate: https://www.ibo.org/globalassets/digital-toolkit/presentations/1711-presentation-history-of-the-ib-en.pdf

IFLA School Libraries Section Standing Committee. (2015). IFLA School Library Guidelines. Retrieved from IFLA School Libraries: https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/9512?og=52

Knapp, P. B. (1966). The Monteith College Library Experiment. New York: The Scarecrow Press.

Sheehan, H. (1969). The Library-College Idea: Trend of the Future? Library Trends, 18(1), 93-102.

Shera, Jesse. (1972). Foundations of Education for Librarianship. New York : Wiley-Becker and Hayes.

Stripling, B. K. (2020). The Process and Stance of Inquiry in a Digital World [15: 6] [Video]. School Library Connection.

Tilke, A. (2011). The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program and the School Library: Inquiry-Based Education. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Wallace, D. F. (Ed.). (2007). The Best American Essays. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

27th November 2021 at 12:19 pm #78502This remains my overriding concern.

I was invited to write a feature series for The School Librarian, which is the Quarterly Journal of the School Library Association.

My starting point, which is clear from the title of the series (see below), is where I left off here, and I will, initially, pick up where I left off from the perspective of this series.I do so now in anticipation of the Great School Libraries campaign webinar on 9 December at 7.30 pm GMT, which will see, amongst other things, the introduction of an inquiry-based learning toolkit – more to follow.

—

Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process

—

The School Librarian, Volume 69, Number 1, Spring 2021

The IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto proclaims that the school library is integral to the educational process. The fact that it is not says much about the educational process, or at least the prevailing one, but It also says something about the school library. For the school library to become integral to the educational process – without which it cannot fulfil its educational purpose, and upon which its moral purpose depends – we urgently need to deepen our understanding of both the educational process and the school library. This is imperative, and not for our sake, but for the sake of our children.

This series takes its title from Norman Beswick’s profound insight that the library does not support the classroom – rather, the classroom leads (or should lead) inevitably and essentially to the library. This is less about the classroom or the library than it is about the sustained collaborative effort of both to equip our children with the kind of knowledge that they most need, which is knowledge that will help them to get more knowledge for themselves. This is desirable, because the principal lesson that school teaches should not be, as Illich charged, the need to be taught. This is also necessary, because the failure of school to help children learn how to distinguish useful talk from bullshit, as Neil Postman puts it, leaves them vulnerable to those who would take advantage of them, especially online.

This brings me to the point of this series, which is to reflect on how the school library becomes integral to the educational process. For this I draw on the collective insight of the IFLA School Library Guidelines, which translate the principles of the Manifesto into practical terms. The Guidelines frame learning through the process of inquiry, which reflects an evolution towards inquiry in and through the school library that can be traced back to 1960, and inquiry, I have come to believe, is the only way for the school library to become integral to the educational process. The reason for this is that inquiry is an educational process – a countervailing one that centres education in the learning process, rather than in the teaching process, encourages initiative and independence on the part of the student, and brings the student to grips with original thought as expressed in books and other media. This, in turn, requires a model of the inquiry process, which is also the means for collaboratively structuring teaching around a framework of skills that students must develop at each stage in the inquiry process over their time in school and in the context of subject area learning.

FOSIL is such a model and framework of skills, and the perspective from which I will write this series. For a brief history of FOSIL and the FOSIL Group, see here: https://fosil.org.uk/history/.

The FOSIL Group is an international community of educators who frame learning through inquiry, which is a process and stance aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society.

The School Librarian, Volume 69, Number 2, Summer 2021

If the school library is to become integral to the educational process, we need to account for why the classroom does not lead inevitably and essentially to the library. This is a complex problem, aspects of which we have no direct control over. Jesse Shera, in The Foundations of Education for Librarianship, charged that “librarians have never developed a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience [in response to the] characteristic information needs of inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalized learning”. While this alone will not solve our problem, developing such a theory is under our direct control, without which we remain peripheral to the educational process at best.

Depending on how globally-minded we are, more or less progress has been made towards such a theory. As Daniel Callison notes, the evolution towards inquiry has been underway since 1960, which is reflected in the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015), which frame learning through inquiry; this evolution is also gathering pace, so much so that inquiry is the subject of an upcoming IFLA publication provisionally titled Global Action on School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (2022). In further observing that the school library exists as a learning centre because of inquiry, Callison makes the logic of our emerging theory explicit – inquiry is an educational process that has characteristic information needs that the library is fundamentally suited to meeting, provided that the librarian understands their role in meeting these needs, which is not limited to resources and/ or information literacy.

Arming ourselves with this emerging theory is not, again, enough on its own, mainly because the prevailing educational process, at least in this country, is not based on inquiry, at least not yet. We do not, however, have the luxury of waiting for this to change, because being peripheral to the educational process is but one step away from being unnecessary. Rather, we must “be the change we want to see happen” (popularly misattributed to Gandhi). In doing so, we will find allies, whether individual teachers, entire departments, or even whole schools. We will, however, inevitably also meet with more or less resistance, which is why we need to be increasingly well-grounded in theory-informed practice.

In this, FOSIL serves us well. I have written about FOSIL’s past – https://fosil.org.uk/history/ – but more relevant here is its future, which, in close collaboration with Barbara Stripling and the growing FOSIL Group community, is the subject of a chapter in Global Action on School Libraries: Models of Inquiry.

More than ever, Gil Scott-Heron’s words strike a powerful chord – the revolution will not be televised.

The School Librarian, Volume 69, Number 3, Autumn 2021

In preparing for my presentation with Barbara Stripling at #SLALeaders 2021, I uncovered Norman Beswick’s extraordinary article for Library Review titled, ‘The Past as Prologue: Two Decades of Missed Chances’. He writes:

It is heartbreaking to recall that in 1970 it was possible to be very hopeful that a great new age of British school librarianship was about to dawn. It did not happen: and this despite the best activities of some school librarians and some local education authorities; and despite some positive statements by professional associations, and some research projects and official reports. It could be important to ask what went wrong. Although the circumstances may not recur, asking the right questions might give us helpful answers for when the campaign for school libraries starts again, tomorrow morning.

I wondered whether, writing today, the article might need to be titled, ‘The Past As Prologue as Past as Prologue: Five Decades of Missed Chances‘. While it remains important, and increasingly urgent, to investigate in detail what went wrong, now is not the time to do so. However, it is opportune to frame our inquiry.

Harold Howe, United States commissioner of education during the Johnson administration and senior lecturer emeritus at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, incisively observed that “what a school thinks of its library is a measure of how it feels about education”.

Howe’s observation demands a response. Given the generally poor condition that we find ourselves in, it is understandable why our response might be to demand that the school thinks more highly of its library, and to redouble our efforts to focus attention on the library. This, however, misses Howe’s profound point, which is that what a school thinks of its library is a consequence of what it feels about education. Therefore, to change what the school thinks of its library, we, if necessary, must change how it feels about education. This, in turn, requires a preoccupation with being integral to the educational process, or, where necessary, agitating for an educational process that the library is integral to, which, as we have argued, is an inquiry learning process.

Given that we are dealing with the reality of five decades of missed chances, most beyond our direct control, we have our work cut out for us. To keep us focused, as Dallas Willard reminds us, the true measure of success is how well we deal with reality.

The revolution will not be televised.

The School Librarian, Volume 69, Number 4, Winter 2021

Imminent.

14th January 2022 at 8:01 am #78557The School Librarian, Volume 69, Number 4, Winter 2021

My appointment as Head of Inquiry-Based Learning at Blanchelande College has allowed me to reflect more deeply on the development of a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience (Shera) and personal growth, which is necessary if we are to change the way our colleagues think of the school library by changing how they feel about education (Howe).

Our starting point is Shera’s assertion that the fundamental philosophical question that we address is, “What is a book that man may know it, and a man that he may know a book?” It is clear from Shera’s writing that he understood book as “record, in the widest McLuhan-like sense” (Beswick). The question then becomes, “What is a record that a person may know it, and a person that they may know a record?”

From the perspective of the development of a theory of the role of the library in the student’s educational experience, our concern, then, is with how a person comes to know a record, or, more specifically in our context, how a student comes to know and understand the world and themselves in it through the record of human knowledge. This, as we have argued, is a learning process, and specifically an inquiry learning process, which is largely dependent on thoughtful reading, both nonfiction and fiction. And this, as we have further argued, is the fundamental purpose of the school library, which closely aligns it with the fundamental purpose of the school. In this way, the library actually becomes integral to the educational process.

From the perspective of FOSIL, this deepening insight into an emerging theory of the role of the library in the student’s educational experience coincides with two important events.

Firstly, the imminent publication of IFLA’s Global Action on School Libraries: Models of Inquiry. This includes a chapter on the evolving nature of inquiry (co-authored with Barbara Stripling), Barbara’s chapter on Stripling’s Model/ESIFC, my chapter on FOSIL (which is based on Stripling’s Model/ESIFC), and a chapter on FOSIL in A-Level Politics at Oakham School by Joe Sanders and Jenny Toerien.

The second is the upcoming IFLA School Libraries Section midyear meeting in April, which we are hosting at Blanchelande College, a focus of which is inquiry-based learning.

These events reaffirm the centrality of inquiry to the library’s instructional program, and the value of the library’s instructional program to the fundamental purpose of the school.

The revolution will not be televised.

14th January 2022 at 9:47 am #78558Darryl as always your insight is fascinating and brilliant timing! I am about to register for a talk/session at the TLConference in Leeds in June and was trying to find an angle that would encourage any Headteachers or SLT into my talk. I think I have just found my answer. I will write the title and abstract using your information above and maybe we can find time to discuss it before I submit it.

Thinking of this as a Title to start with

Catch 22 – What you don’t know until someone tells you. The school library; an integral component of the education process.

13th March 2022 at 1:53 pm #78704Sorry, Elizabeth, I missed this post in the the build up to the house move, although, as it turns out, we ended discussing your talk/ session anyway.

How did it go?

The School Librarian, Volume 70, Number 1, Spring 2022

I write this from the perspective of a new year in a new country (Guernsey), new school (Blanchelande College) and a new role (Head of Inquiry-Based Learning), so an added measure of reflection is to be expected.

I am particularly mindful of Octavia Butler’s warning in the Parable of the Talents (1988):

When vision fails/ Direction is lost.

When direction is lost/ Purpose may be forgotten.

When purpose is forgotten/ Emotion rules alone.

When emotion rules alone,/ Destruction… destruction.

Why?

Inquiry, as an instructional approach to curriculum content, to which the library is integral, provokes an emotional response. This is good, insofar as emotion serves a purpose, and in the case of education, a “transcendent and honorable purpose” (Postman, 1996).

This is important for two reasons.

Firstly, purpose gives shape to resolve. I have long held that the fundamental purpose of the school library is to enable students to come to know and understand the world and themselves in it through reading, both nonfiction and fiction. This process of coming to know and understand is a learning process, and specifically an inquiry learning process. This purpose, in turn, aligns the school library with the fundamental purpose of school – knowledge and understanding – regardless of whether the school, or the broader educational system in which the school operates, favours an inquiry-based approach to teaching and learning or not. In the service of this purpose, the school library expresses its essential nature, and finds allies in those colleagues who view the educational process in the same way. The particular shape that my resolve takes, then, and which is enacted through the library programme, is to enable reading for knowledge and understanding within an inquiry-based model of the learning process, and this within the curricular constraints of UK GCSE and A-Level qualifications. Having clear shape to my resolve helps me to balance impossible demands on my time, which goes a long way towards ensuring a balanced library programme.

Secondly, purpose strengthens resolve. In choosing to work in a school library, I am choosing to serve a “transcendent and honorable purpose”. This lifts my eyes above the struggles of today to the hope of a better tomorrow – one that I strive towards with likeminded colleagues, both near and far. In doing so, I am preparing myself, my colleagues, and my students for a future that will make demands of us that the school library uniquely equips us to meet.

The revolution will not be televised.

12th June 2022 at 9:06 am #78989The School Librarian, Volume 70, Number 2, Summer 2022

Writing this while looking ahead to the IFLA School Libraries Section Midyear Meeting at Blanchelande College on 21-22 April 2022 brings into focus diverging historical trajectories for school libraries – one leading to a future in which it is integral to the educational process, the other continuing to a future in which it is not.

Now, as I have argued, the school library is integral to the educational process, but only if it is understood in a certain way. Understanding this is vital, if not to our success, then to our survival. The reason for this is that our concern, as librarians, lies first and foremost with this educational process, and then with our role in this process. Ruth Davies expresses this idea powerfully:

Today’s school library is a source and a force for educational excellence, and today’s school librarian “is a teacher whose subject is learning itself” (quoting Douglas Knight).

This idea no longer animates us.

However, writing this while looking back on 85 years of the School Library Association reminds us that history is the consequence of ideas.

Richard Colebourn, in his personal survey of the first 50 years of the SLA, makes the point that from the outset “the Association…was clearly envisioned as an organisation of, and for, educationalists”. Cecil Stott, joint honorary secretary, underscored this view in his report for the inaugural meeting in January 1937, that while efficiency and technique were important, they were only so “as a preliminary to the far more important use of the library as an instrument of education”. It is worth noting that the “educational use” and “educational function” of the school library remain Association priorities, at least in Colebourn’s survey, into the 1970s.

Yet, by 1986, Norman Beswick, who Colebourn references in the highest regard, laments the passing of this idea – that the school library is a source and a force for educational excellence because the school librarian is a teacher whose subject is learning itself. And yet, this idea remains at the heart of the revised Manifesto (2022), which, in turn, revitalises the School Library Guidelines (2015) and is reflected in Global Action on School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (2022).

Perhaps heightened reflection on 85 years of service to our local profession combined with greater engagement with our global profession will help us to recover an idea from our past that will prove vital to our future?

The revolution will not be televised.

18th September 2022 at 5:12 pm #79121The School Librarian, Volume 70, Number 3, Autumn 2022

This series addresses Jesse Shera’s charge that “academic librarians have never developed a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience,” specifically in response to the “characteristic information needs of inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalized learning.” Should we be tempted to shift responsibility for this to someone else, namely academic librarians, Blanche Woolls reminds us that, eventually, the only difference between an academic librarian and a school librarian is the time between a student leaving school and starting university. And, according to Kachel and Lance, this abiding ‘disconnect’ is likely a major contributor to the ongoing losses of school librarians, which are commonly justified on financial grounds.

Now, as Ruth Davies reminds us, when there is no ‘disconnect’ between the school library program and the school’s educational program – when the school library is integral to the educational process – then the school library program becomes an instructional source and force for excellence. Again, should we be tempted to shift responsibility for this to someone else, namely the school, she points out that “perspective in viewing the function and role of the school library…program begins logically by building a historical understanding of education itself.” This brings our situation, and task, into sharp focus.

To develop a theory of the school library in the student’s intellectual experience, necessary if the school library is to be(come) integral to the educational process, thereby strengthening us against financially justified cutbacks, we need to start by building our understanding of the educational process and then defining our role in it. This immediately pitches us into battle, because there are competing views on the educational process – which I have addressed in this series and elsewhere – and we must align ourselves, however the odds seem stacked, for us, or against us.

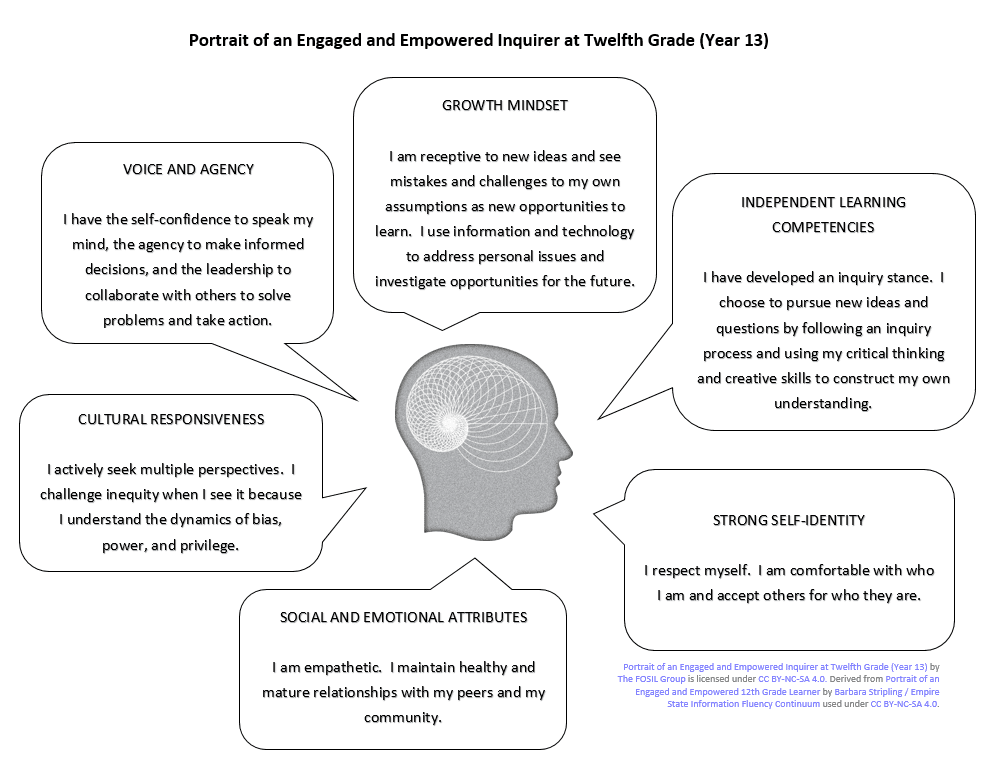

As it turns out, school librarians have made considerable progress on countering Shera’s charge. This work – underway since the 1960s, culminating in the most robust of the models of the inquiry-based learning process in the early 2000s, and ongoing – is reflected in the Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Twelfth Grade (2022, see below). This portrait, developed by Barbara Stripling and Digital Lead Librarians in New York City, is a profound statement on the educational process from the perspective of a school library integral to that process – inquiry has this as its end and is the systematic and progressive means to this end – see FOSIL Group discussion https://bit.ly/3HMj8fA for more detail.

The revolution will not be televised.

10th December 2022 at 10:10 am #79376

10th December 2022 at 10:10 am #79376The School Librarian, Volume 70, Number 4, Winter 2022

The IFLA 2022 World Library and Information Congress (WLIC) saw the launch of the latest book in the IFLA Global Action for School Libraries series, Models of Inquiry (2022), which reaffirms the centrality of inquiry to achieving the school library’s educational and moral purpose, and which included two chapters on FOSIL. These chapters afforded us the opportunity to reflect deeply on a journey that began in earnest in 2011 and resulted in an invitation to contribute a chapter to an upcoming IFLA book on digital literacy, to be launched during the IFLA 2023 WLIC. This chapter afforded me the opportunity to reflect deeply on where this journey is taking us.

In wrestling with this chapter, I gained greater insight into the importance and urgency of our calling as school librarians. In reality, we are pitched into battle on the frontline of the assault on what Jonathan Rauch (2021) terms the Constitution of Knowledge, which is the epistemological operating system of our democracy. This view may seem somewhat extreme from the relative comfort of our school libraries, but evidence continues to mount. Having just observed Banned Books Week – with PEN America, for example, reporting 1,648 unique book titles banned in schools between July 2021 and June 2022, with the rate increasing – we might be tempted to view this assault solely in terms of the books themselves. This, however, misses the real threat, which is an assault on the underlying knowledge-building, or inquiry, process.

As school librarians, then, we serve the Constitution of Knowledge in two vital ways. Firstly, we secure physical access to the growing body of knowledge of reality – as uncovered by the academic disciplines/ subjects and – held in our collections. Secondly, we educate our students in the inquiry process that grows this body of knowledge, so that they become knowledge-able – able, that is, to intellectually access this body of knowledge, and utilise it – thereby strengthening the “reality-based community of error-seeking inquirers” (Rauch) that upholds and is upheld by the Constitution of Knowledge. Failure to do so, as Dallas Willard (1999) warns, leaves us vulnerable to “desire and will/ brute force…as social processes come to be managed by people who simply know how to get their way among a mass of those who no longer believe that they can, with the aid of their culture’s texts and the traditional disciplines, determine how things are…regardless of how anyone wishes them to be or how people with social authority present them”.

The revolution will not be televised.

2nd April 2023 at 6:42 am #80051I continue (and collate) my series – Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process – for The School Librarian, the Quarterly Journal of the School Library Association.

—

The School Librarian, Volume 71, Number 1, Spring 2023

“The greatest events – they are not noisiest but our stillest hours. The world revolves, not around the inventors of new noises, but around the inventors of new values; it revolves inaudibly.” Thus spoke Nietzsche in Zarathustra.

What values, then, are we inventing, around which, in the fullness of time, the worlds of our schools will come to revolve?

About Reading for Pleasure (RfP) we are noisiest, but about why and how the school library is integral to the educational process, less inaudible than silent, and this noisy silence testifies against us.

On the one hand, RfP, while absolutely necessary for a vital school library instructional program,* is not sufficient in and of itself to warrant a school library, and evidence of this continues to mount. Keith Curry Lance – who knows a thing or two about the actual value that a “high quality library program” adds to the educational process in terms of student achievement – and Debra Kachel, in lamenting the mounting losses of school librarians, attribute those losses in large part to a “disconnect” between school librarianship and the larger education community. This disconnect, somewhat perversely, is in part a consequence of a preoccupation with RfP within the school library program. The reasons for this are many and varied, which we will return to.

Therefore, and on the other hand, whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent (with apologies to Wittgenstein). For if, as Ruth Ann Davies points out, perspective in viewing the function and role of the school library program begins logically by building a historical understanding of education itself, then our lack of historical understanding of education silences us on matters of our educational value. Can we, for example, tell Dewey (John) from Dewey (Melvil)? And are we, for example, as intimately conversant with Bruner, Piaget/ Papert and Vygotsky, as we are with Bramachari, Pichon, and Veronica Roth? If not, then those who have and still would testify most eloquently to our value necessarily stand mute.

The revolution will not be televised.

*Essentially: literacy and reading promotion (includes appreciation of literature and culture); inquiry-based teaching and learning (includes media and information literacy); technology integration; professional development for teachers. Of course, this is a big ask, possibly impossibly so, given our currently dire state of affairs, but that is precisely the point – we are (re)valuing a vital library program that is appropriately funded and suitably staffed.

—

The FOSIL Group is an international community of educators who frame learning through inquiry, which is a process and stance aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society.

28th September 2023 at 10:39 am #81375I continue (and collate) my series – Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process – for The School Librarian, the Quarterly Journal of the School Library Association.

—

The School Librarian, Volume 71, Number 2, Summer 2023

The purpose of this series is to address Jesse Shera’s charge that academic librarians, and by extension school librarians, had never developed a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience, which is not the same as a list of things that a librarian does. This theory, from my perspective, is taking firm shape, and is discernible in the case that I have been making here.

I pause now to reflect on three significant developments that bring this theory into sharper focus.

Firstly, following the IFLA School Libraries midyear meeting at Blanchelande College in April 2022, I was invited to write a chapter for an upcoming IFLA book on digital literacy.* Having already argued at the UK SLA conference in June 2021 that inquiry was an imperative for the library if we are to become integral to the educational process in school, this chapter enabled me to argue that inquiry is an imperative for school if we are to adequately strengthen the reality-based community of error seeking inquirers who uphold the Constitution of Knowledge upon which liberal democracy depends (Jonathan Rauch).

Secondly, this emphatically reaffirms Neil Postman’s assertion that of all the survival strategies that education has to offer, none is more potent than inquiry, provided that we resist the tendencies that rob inquiry of its potency. We will explore this in detail and at length during an extended workshop at the IASL conference in Rome in July 2023.

Thirdly, growing interest in and adoption of FOSIL in Australia, including by students on the M.Ed. (Teacher Librarianship) program at Charles Sturt University, brings with it a wealth of theoretical knowledge and practical experience, especially as a number of these colleagues are moving from well-established Guided Inquiry Design programs to FOSIL.

The revolution will not be televised.

*My chapter – Digital Literacy: Necessary but Not Sufficient for Life-wide and Life-long Learning – prompted me to revisit my presentation at LILAC in April 2019 – Information Literacy: Necessary but Not Sufficient for 21st Century Learning – which coincided with the launch of the FOSIL Group. The formation of the FOSIL Group, in turn, was the unintended but inevitable outworking of my presentation at the CILIP SLG conference in April 2018 – Information Literacy Framework(s): The Next Step(s) – which identified an urgent and growing need to support colleagues who were beginning to develop information literacy skills systematically and progressively within an inquiry-based learning process.

—

The FOSIL Group is an international community of educators who frame learning through inquiry, which is a stance and process aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society.

28th September 2023 at 10:45 am #81376I continue (and collate) my series – Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process – for The School Librarian, the Quarterly Journal of the School Library Association.

—

The School Librarian, Volume 71, Number 3, Autumn 2023

In September 2021, I was appointed at Blanchelande College as Head of Inquiry-Based Learning and am the first Librarian in the College’s long history. In May 2023, Blanchelande was shortlisted for the SLA Enterprise of the Year Award. The Award is an opportunity to demonstrate this column’s thesis, which is that the library becomes integral to the educational process through the purposeful implementation of its inquiry-centred instructional programme as outlined in the IFLA School Library Guidelines, even within a GCSE and A-Level educational pathway.

The library becoming integral to the educational process at Blanchelande was not inevitable.

As the Principal, Rob O’Brien, explains: Although the creation of a well-proportioned library space and a suitable budget was a highly significant and symbolic statement of intent, this material and financial aspect proved to be comparatively simple to achieve. Our vision was for a library that facilitates liberal education in the truest sense – students capable of independently inquiring into subjects and learning to question perceptively and think deeply. However, it took the appointment of a librarian with deep insight into the inquiry process and the subsequent creation of an Inquiry-Based Learning department for us to begin using this vital resource to effectively equip students (and their teachers) with the knowledge that enables them to get more knowledge for themselves.

This powerfully illustrates Harold Howe’s profound observation that what a school thinks of its library is a measure of how it feels about education. On the one hand, the College’s view of education allowed for a library that was integral to the educational process. On the other hand, this required a librarian who could describe what such a library looks like and does, and explain how it becomes so. For this the Guidelines were necessary but not sufficient. While the Guidelines translate the principles of the IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto into practical terms, it falls to us, individually and as a profession, to wrestle these principles into actual practice. Without realising it at the time, this is what I had been doing since becoming a school librarian in 2003, a struggle that led to FOSIL in 2011 and the FOSIL Group in 2019, and that leads still further on.*

The revolution will not be televised.

*This personal journey, upon reflection, mirrors the evolution of the library’s instructional focus from information literacy in the first edition of the Guidelines (2002) to information literacy within an inquiry process in the second edition of the Guidelines (2015).

—

The FOSIL Group is an international community of educators who frame learning through inquiry, which is a stance and process aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society.

18th December 2023 at 3:34 pm #82164I continue (and collate) my series – Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process – for The School Librarian, the Quarterly Journal of the School Library Association.

—

The School Librarian, Volume 71, Number 4, Winter 2023

Following the SLA Enterprise of the Year Award <tinyurl.com/4v9vpxyj>, we travelled to the IASL Annual Conference in Rome. This provided a further opportunity to demonstrate theoretically and practically how the school library/ian becomes integral to the educational process through its inquiry-centred instructional program as outlined in the IFLA School Library Guidelines, which included demonstrating how inquiry, and specifically ESIFC/FOSIL-based inquiry, counters all four debilitating tendencies that rob inquiry of its educational potency <tinyurl.com/yc23e5yt>. I then presented my chapter – Digital Literacy: Necessary but Not Sufficient for Life-Wide and Life-Long Learning – for an upcoming IFLA book at the World Library and Information Congress in Rotterdam. This provided an opportunity to argue further that a library/ian-centred educational process in school makes school integral to broader efforts to strengthen the “reality-based community” of “error-seeking inquirers” (Rauch, 2021) on which liberal democracy depends <tinyurl.com/u4m47m3j>. This – a school library/ian integral to the educational process, and an educational process integral to strengthening the fabric of democratic society – requires the school library/ian to understand themself as “a teacher whose subject is learning itself” (Knight, 1968).

This, by and large, is not who we currently are as a profession, although it could be who we aspire to be, given suitable inspiration. This makes the recent SLA publication of Making School Libraries Integral to the Educational Process: An Introduction to the IFLA School Library Guidelines especially timely, given (1) the inspirational and aspirational force of the Guidelines, which derives from more than 50 years of international research into the effectiveness of school libraries, and (2) a widespread and growing concern with the instructional identity of a school librarian, or lack thereof, which the Guidelines treat as of fundamental importance.

Lance and Kachel (2021) recently lamented mounting school librarian job losses, often motivated on financial grounds but more broadly driven by a disconnect between school librarianship and education. Davies (1979), perhaps more prophetically than she intended, warned:

Because [of the] persistent downgrading of education, the profession itself must make a value judgment as to which criticisms from without the profession and which criticisms from within it are justified. Having identified the legitimate criticisms, the profession must then painstakingly set about to correct what is wrong, to strengthen what is weak, and to safeguard what is excellent. “The whole aim is to lift the critique from a set of complaints to a set of purposes” (Barzun, 1978). Only then can a plan for action be formulated and disaster, always lurking in the wings, be forestalled.

The revolution will not be televised.

—

The FOSIL Group is an international community of educators who frame learning through inquiry, which is a stance and process aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society.

23rd October 2024 at 8:31 am #84775Volume 71, Number 4, Winter 2023 above was the last in this series of Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process for The School Librarian, the Quarterly Journal of the School Library Association.

However, starting with Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process 2.1 below, I continue this series for the School Library Association Blog.

—

Between the Library and the Classroom: Becoming Integral to the Educational Process 2.1

“Of all the ‘survival strategies’ education has to offer, none is more potent or in greater need of explication than the ‘inquiry environment'” (Postman & Weingartner, 1969, p. 36).

An educational inquiry environment is potent because and to the extent that it develops engaged and empowered inquirers. This is because inquiry is how we, individually and collectively, acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to deal successfully with reality, which, in the final analysis, is the only true measure of human success.

Our collective failure to deal successfully with reality is painfully and alarmingly evident, as even a glance at any day’s news headlines will confirm, which is a consequence of our failure to establish an effectual inquiry environment in school.

However, the school library is by its very nature an inquiry environment, and it is, therefore, both a vital enabler and driver of inquiry within school. This makes the school library integral to the education process of school, properly understood. This also, then, positions the school librarian(s) on the frontline of the struggle to shape the answer to, as John Dewey (1956) puts it, the “fundamental … question of what anything whatsoever must be to be worthy of the name of education” (p. 17).

The future of school libraries, and that of our children, hinges on the shape of the answer to this question.

Now, the potency of any given school library will depend on the extent to which it is true to its nature, which is not solely and/ or fully under the control of its librarian(s). This is because any given school will itself only ever be a more or less vital and enabling inquiry environment. This is a complex situation that exists between the library and the classroom, and one that requires explication, still. And this brings us to the purpose of this series of blog posts, which is an online continuation of my defunct TSL column of the same name (plus 2.n), the articles of which have been collated in the FOSIL Group forum, A theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience.

I will continue this work of explication every 2 months, with the next post developing the argument outlined here more practically. However, as the eventual shape of the answer to the question of what is worthy of the name of education and its outworking for our profession will emerge out of professional conversation, I will in the meantime, as time permits, join in the conversation here.

The revolution will not be televised.

References

- Dewey, J. (1956). Experience and Education: Selections. In Great Issues in Education (Vol. II, pp. 3-17). Chicago, IL: The Great Books Foundation.

- Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York, NY: Delacorte Press.

—

The FOSIL Group is an international community of library- and classroom-based educators committed to building an effectual inquiry environment in primary-secondary / PK-12 education.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.