E&L Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry

Barbara Stripling | November 8, 2020

UncategorisedSeymour Papert led the Epistemology and Learning Group, later the Future of Learning Group, in the MIT Media Lab, during which time he authored the Epistemology & Learning Memos – deliberations on how children learn to know and understand. The FOSIL Group Epistemology & Learning Memos honour this service to children and are offered in this spirit.

—

E&L Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry by Barbara Stripling

Introduction by Darryl Toerien (8 November 2020)

Seymour Papert (1993) argued that the kind of knowledge children most need is knowledge that will help them get more knowledge. This epistemological concern – a concern with what knowledge is and how we get knowledge – is the starting point for our deliberations on how children learn to know, because what we think about learning, and therefore education (especially in schools), depends on what we think about knowledge.

The Galileo Educational Network describes inquiry as “a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world, and as such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created”. Inquiry, then, is a fundamental human activity out of which libraries were born, in initially as storehouses of knowledge. Although school libraries are a recent development by comparison (Wiegand & Davis, 1994, p. 564), as Daniel Callison (2015) points out, “the progression to student-centered, inquiry-based learning through school library programs was clearly underway more than forty years ago” (p. 3), at least in the US, and can be traced back to 1960 (p. 213). More broadly, though, Callison lists the International Baccalaureate (IB) Programme as an early adopter of inquiry (p. 214), with the philosophy, structure, content and pedagogy of the IB Diploma Programme being developed in 1962 (IBO, 2017). This means that inquiry as a dynamic process that unfolds in and through the school library is increasingly well understood, if not equally well supported. Consequently, a number of highly successful instructional models of the inquiry process have been developed, such as Carol Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process / Guided Inquiry Design and Barbara Stripling’s Model of Inquiry / Empire State Information Fluency Continuum. Of particular interest to us here, is the model developed by Barbara Stripling, because this is the model that FOSIL is based on (see here for a history of FOSIL updated 18 September 2020).

A model of the inquiry process is necessary if we are to effectively equip our children with the kind of knowledge that will enable them to get more knowledge for themselves, but it is not sufficient. As Barbara points out, we then need “to structure teaching around a framework of the literacy, inquiry, critical thinking, and technology skills that students must develop at each phase of inquiry over their years of school and in the context of content area learning” (2017, p. 52, emphasis added). In doing so, librarians and teachers are united in the task of “influencing, orienting, and motivating the pursuit of learning using a process of discovery that encourages curiosity and a love of learning” (IFLA School Library Guidelines, 2015, p. 43). And this, in turn, would take us some way towards providing schooling with the transcendent & honourable purpose necessary for becoming “the central institution through which the young may find reasons for continuing to educate themselves” (Postman, 1996, pp. x-xi).

Given that Barbara’s work on learning to know and understand through inquiry stretches back further even than the publication in 1988 of the ground-breaking Brainstorm and Blueprints: Teaching Library Research as a Thinking Process (Stripling & Pitts), her collaboration on the ongoing development of FOSIL through the FOSIL Group brings with it a professional lifetime’s worth of insight borne of thoughtful experience.

Bibliography

- Callison, D. (2015). The Evolution of Inquiry: Controlled, Guided, Modeled, and Free. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

- IBO. (2017). The history of the IB. Retrieved from International Baccalaureate: https://www.ibo.org/globalassets/digital-toolkit/presentations/1711-presentation-history-of-the-ib-en.pdf

- Papert, S. (1993). The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. New York: Basic Books.

- Postman, N. (1996). The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. New York: Vintage Books.

- Stripling, B. (2017). Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment. In S. W. Alman (Ed.), School librarianship: past, present, and future (pp. 51-63). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Stripling, B. K., & Pitts, J. M. (1988). Brainstorm and Blueprints: Teaching Library Research as a Thinking Process. Englewood: Libraries Unlimited.

- Wiegand, W. A., & Davis, D. G. (Eds.). (1994). Encyclopedia of Library History. New York: Garland Publishing.

—

Barbara Stripling

My path to inquiry started early in my career as a librarian. I had been an English teacher in middle school and high school, but I realized when I became a librarian that I had never thought about the skills and process that underlay the learning of content. As a classroom teacher, I had expected my students to probe for deep meaning in the literature we tackled, but I had never taught them the critical thinking skills they needed to find that meaning. I had been generating all of the questions to be asked, not empowering the students to ask their own questions. I had been figuring out the deep meaning of each piece and then expecting my students to write essays and responses about why my deep meanings were true.

With that epiphany about my own practice and the realization that I needed to teach students how to learn and build their own knowledge, not just to find information or parrot knowledge created by someone else, I was propelled to explore and make sense of how people learn. As I reflect on my own path of discovery, I recognize that I engaged in a years-long inquiry process myself as I pursued different lines of inquiry in a messy and recursive process. For each line of inquiry below, I have tried to capture what I learned and how I translated that knowledge into practice by developing an application or model.

Educational Philosophy: John Dewey

The foundation of my approach to inquiry and learning can be traced to John Dewey and the educational philosophy presented in Experience & Education (Dewey, 1938). My copy is covered with post-it notes and highlighting, because I have continued to go back to this ground-breaking presentation of education as experience. Although Dewey has certainly not been the only influence on my own educational philosophy, I can see the roots of my thinking and my inquiry model in his treatise.

I connected with Dewey at a fundamental level when he defined the purpose of education. Dewey said, “The main purpose or objective is to prepare the young for future responsibilities and for success in life” (p. 18). I translated that broad purpose into my vision as a school librarian: the goal of school librarians is to empower students to be independent learners for life. That vision has guided most of my professional work.

I found that Dewey’s thinking helped guide decisions I have made about my professional practice. Dewey focused on education as experience, but he defined the parameters of experiences that lead to “genuine education.” Experiences must include both “acquisition of the organized bodies of information” and “prepared forms of skill which comprehend the material of instruction” (p. 18). Dewey’s recognition of the need for both content and skills provided solid justification for the role of a school librarian as a teacher of sense-making skills. I recognized that skills must be integrated into the teaching of content to enable learners to comprehend information and build knowledge.

Dewey also focused on the importance of continuity of experience: “. . .every experience both takes up something from those which have gone before and modifies in some way the quality of those which come after” (p. 35). In other words, students’ prior knowledge and experiences provide a basis for current learning, which then must lead to future experiences and further learning. I explicitly incorporated that understanding about the continuity (and authenticity) of learning when I developed the Stripling Model of Inquiry by envisioning it as a cycle that begins with connecting to prior knowledge and results in reflecting and asking further questions to propel the next inquiry.

Dewey’s philosophy supports a student-centered, rather than teacher-centered, approach. He stated that teachers have a responsibility for setting objectives based on “. . .understanding the needs and capacities of the individuals who are learning at a given time” (p. 45). My translation of that approach has been to develop and publish a PK-12 continuum of inquiry, literacy, and information literacy skills in order to provide a path for continued development of information fluency.

Finally, I see the roots of my focus on inquiry learning that engages students in authentic inquiry and active construction of new understandings in Dewey’s description of the educator’s responsibility: “First, that the problem grows out of the conditions of the experience being had in the present, and that it is within the range of the capacity of students; and, secondly, that it is such that it arouses in the learner an active quest for information and for production of new ideas” (p. 79).

Critical Thinking

As soon as I became a school librarian and recognized my mandate to teach the process and thinking skills of independent learning, I realized that I did not actually know much about critical thinking. Certainly, I knew Bloom’s Taxonomy, but I needed a much deeper dive into identifying specific skills and understanding the process the mind goes through to perform each skill. I, personally, knew how to make inferences, but if I were attempting to teach a young learner who did not know how to infer, I needed to identify the mental steps required to make an inference. A logical step in my learning journey, then, was to investigate the literature and research about critical thinking.

I discovered numerous authors and thinkers who offered rationales for teaching students to think and embedding a thinking curriculum into schools. Arthur Costa edited a compendium of short articles (Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking) that explored the whole realm of teaching thinking, with chapters written by leading experts in the field (Costa, 1991). Those overview articles defined the concepts of critical and creative thinking, explored alternatives for integrating thinking into the curriculum, and offered guidance for teaching thinking effectively. I was influenced by Shelley Berman’s contribution about open-mindedness, characterized by collaborative thinking, focusing on questioning rather than finding answers, thinking about systems and the interconnectedness of ideas, and adopting multiple perspectives (Berman, 1991).

Richard Paul provided a primer on essential thinking skills by enumerating specific cognitive and affective strategies (Paul, 1991). His article provoked me to start thinking about the intellectual dispositions that should be fostered concomitantly with thinking skills, including intellectual curiosity, courage, humility, empathy, integrity, perseverance, and fair-mindedness.

Carol Booth Olson contributed an article that prompted me draw on my English-teacher experiences in teaching writing (Olson, 1991). . For example, I taught my students reflective, two-column notetaking, a strategy that I learned from professional workshops on teaching writing.

One of the more valuable aspects of Developing Minds for the development of my own thinking was the mention of graphic organizers. Early in my exploration of thinking skills, I recognized the importance of teaching the underlying, step-by-step process of every thinking skill to enable students to master the skill. I began developing graphic organizers to help students demonstrate their ability to perform each step of the process. The added benefit of graphic organizers is their usefulness as authentic, formative assessment tools – students are able to demonstrate their ability to perform a skill and develop knowledge and understanding. I have continued to develop graphic organizers over the years, culminating in over 200 created for the latest edition of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (Stripling, 2019).

I read widely in the area of critical thinking and absorbed the insights of many respected educators, including Jay McTighe, Art Costa, Robert Ennis, Barry Beyer, and Richard Paul. I found Tactics for Thinking by Robert J. Marzano and Daisy E. Arredondo to be especially useful in teaching the step-by-step process of a number of thinking skills, including concept development, pattern recognition, synthesizing, evaluation of evidence, and decision making (Marzano and Arredondo, 1986).

Recently, I have found Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DOK) (first published in 1997) to be a valuable framework about the levels and complexity of thinking demanded of our students in all content areas. In 2002, Webb laid out four levels for acquisition of deep knowledge as they could be applied to reading, writing, mathematics, science, and social studies: Level 1 – Knowledge Acquisition; Level 2 – Knowledge Application; Level 3 – Knowledge Analysis; and Level 4 – Knowledge Augmentation (Webb, 2002). Although many educators use the graphic DOK wheel (origin unknown) as a simple guide to integrating DOK into their instruction, experts have explained that the wheel is limited and that educators must design instruction to push students beyond the verbs of the wheel to analyze and augment their knowledge and reach deeper understanding (see Francis, 2017). Webb’s approach strengthens my own philosophy of school librarianship – that we must integrate thinking skills with content in all subject areas, that we must push students to think more deeply and critically than simple knowledge acquisition, that we can help students reach deeper understanding when we help them connect their learning to authentic and original applications, and that we must motivate students to extend their learning beyond one experience.

Research as a Thinking Process

When I became a school librarian, I recognized that the teachers were focused entirely on delivering the content of their curricula to their students. Most of the students dutifully scooped in the content and spouted it back on tests and other assignments. Students were rarely given an opportunity to gather or make sense of information on their own. If they were given any time to research, it was often a one-day, fact-grab situation. My fellow librarian, Judy Pitts, and I to guide both teachers and students through ten steps of asking questions, gathering credible information, establishing conclusions, and presenting a final product. We embedded instruction in thinking skills throughout the process and, through collaboration with classroom teachers, integrated our instruction into classroom units across the curriculum (of course, we did not convince every teacher).

The research process we wrote about in our book, Brainstorms and Blueprints: Teaching Library Research as a Thinking Process, was linear, replete with examples of library instruction in thinking skills, and focused on empowering students to do the thinking (Stripling and Pitts, 1988).

Authentic Instruction and Assessment

At the same time that Judy Pitts and I were developing our research process, I began investigating authentic learning and assessment. Prominent educators were writing about alternative forms of assessment, such as exhibitions and portfolios, that had the potential to lift students’ learning from repetition of approved knowledge to demonstrations by the students that they were able to apply that knowledge in their own way.

I was committed to collaborating with teachers to lift the assignments that involved research to a new level. I hoped to figure out ways of demonstrating learning that could not be simply copied and that were engaging and interesting for both teachers and students.

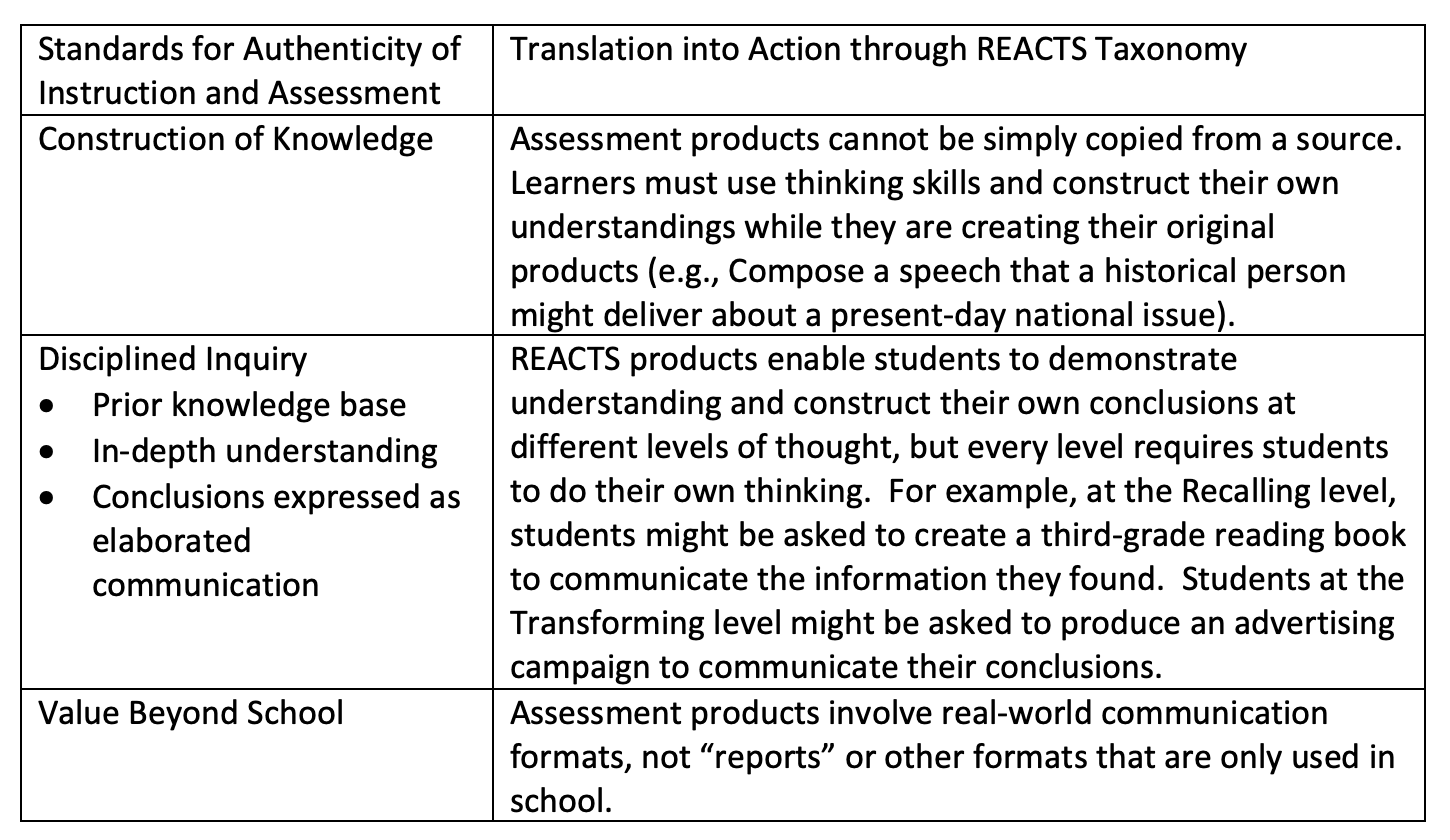

I started researching authentic learning and assessment, a concept that I knew little about, but one that seemed to hold promise for making assessment part of the learning process and not just a rote recitation of facts or ideas that were soon forgotten. The most influential book that I read in my investigation was A Guide to Authentic Instruction and Assessment: Vision, Standards and Scoring by Fred M. Newmann, Walter G. Secada, and Gary G. Wehlage (1995). The authors proposed three standards for authentic academic achievement – construction of knowledge, disciplined inquiry, and value beyond school. I translated those ideas into my own language so that I could see how they might apply to my own situation in the library.

Our library response to “construction of knowledge” was to collaborate with classroom teachers to design experiences that required students to engage actively to build their knowledge by using thinking skills like evaluation, analysis, and synthesis. Furthermore, the students should be expected to construct their own understanding by producing original expressions of their knowledge. I recognized that “disciplined inquiry” in the library could be implemented through a well-structured research process that started with what students already knew and culminated with their original products and their reflections on what they had learned.

The “value beyond school” aspect of authenticity was the most intriguing new idea that this area of exploration brought to my work. Judy Pitts and I began to envision student assessment products that were authentic ways that people communicate in the real world. We developed a Taxonomy of Research Reactions, called REACTS (Recalling, Explaining, Analyzing, Challenging, Transforming, and Synthesizing). The REACTS Taxonomy suggested example research products at six levels of complexity that resembled Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain (Note: We flipped the two highest levels of the original Bloom’s Taxonomy because we felt that synthesis was a higher level of thinking than evaluation. The Anderson and Krathwohl revision in 2001 of Bloom’s made the same switch.).

The chart below captures some of our thinking as we translated the standards for authenticity from Newmann et al. into our REACTS Taxonomy.

The REACTS levels were described in detail in Brainstorms and Blueprints and have been expanded and updated to include digital skills and products over the years (see Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, 2019, https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc).

The incorporation of the principles of authentic learning and assessment into my practice as a school librarian and school library administrator profoundly influenced my effectiveness as a teacher and a collaborator. Fellow librarians, classroom teachers, and students actively embraced authentic learning experiences that involved opportunities for students to think on their own and feel confident in the conclusions they drew, to use their own imaginations to create and share interesting products and show a deep understanding of the subject, and to connect learning in school with the outside world of information and communication.

Designing Instruction to Teach for Understanding

Once I had developed some degree of confidence in the application of critical thinking skills and authentic learning and assessment to a thought-provoking research process, I began to consider the larger concept of instructional design. I needed to shift my perspective from library-centric to teacher-centric in order to collaborate effectively and have an impact on the instructional culture of the school. The model of instructional design proposed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in Understanding by Design moved my thinking about designing instructional units from the linear approach that was my comfort zone (Step 1, Step 2. . .) to a backwards design process (Wiggins and McTighe, 1998).

Subconsciously, I had probably been leaning that way (e.g., focusing on authentic assessment products as the outcome of research projects), but shifting explicitly to the Wiggins/McTighe backwards design process changed my collaborative conversations with teachers, my commitment to students’ development of understanding rather than simple acquisition of knowledge, and even my lesson planning.

Wiggins and McTighe helped me define what I meant by “understanding” when they identified six facets of understanding: explanation, interpretation, application, perspective, empathy, and self-knowledge. I know that my work to create a full picture of the skills and attitudes of an information-fluent learner was influenced by this multi-faceted description of understanding. My collaborative conversations with teachers shifted substantially when I changed the initial question from teacher-focused (“What are your objectives?”) to student-focused (“What would you like your students to understand as a result of this unit?”). That question opened the door to collaborative design of units to help students probe larger concepts and draw their own conclusions. By focusing on the goal of understanding, the teachers and I found it easier to choose authentic summative assessment products, to integrate the teaching of critical information skills, and to design instructional units that gave students time to think.

As I reflect now, I believe that the concepts of backward design and teaching for understanding were important building blocks in my shift from a teacher-driven, linear research process to a student-driven, cyclical inquiry-process model.

Constructivism and Social Constructivism

Although constructivism as an educational philosophy can be traced back to Jean Piaget, I did not encounter the scholarship around it until halfway through my career. Constructivism essentially defines learning as an active process by learners to construct knowledge out of experiences. Social constructivism expands the individualistic aspects of constructivist learning to recognize the collaborative and social dimensions of learning.

Probably the most influential book that I read on constructivism was The Case for Constructivist Classrooms by Jacqueline Grennon Brooks and Martin G. Brooks (1993). I discovered that the basic description of constructivist teaching was very much in line with my own ideas that learners must construct new understandings from the information they gather and their own experiences. Brooks and Brooks pose some guiding principles of constructivist teaching, all of which made intellectual sense to me (Brooks and Brooks, 1993, p. 33):

- Posing problems of emerging relevance to students

- Structuring learning around primary concepts: The quest of essence

- Seeking and valuing students’ points of view

- Adapting curriculum to address students’ suppositions

- Assessing student learning in the context of teaching

Brooks and Brooks provide guidance and numerous examples for teaching in a constructivist way that incorporates their guiding principles. After studying constructivism, I became convinced that this educational theory had great implications for my practice.

Logically, I then decided to implement constructivism in my own teaching. I still remember the first day I tried. I spent five minutes with a class of around 30 students who were starting to gather information for their research projects. I provided the learning goal and context, then I turned them loose to discover on their own how to evaluate and select credible information sources. I watched as they scattered throughout the library (a large and L-shaped facility). I lasted for about 5 minutes until I became overwhelmed by my own insecurity. What if they did not discover the principles of evaluation that I thought they needed to learn? What if they applied wrong principles or just grabbed anything they could find? That day, I called them back together and told them the evaluation principles I wanted them to learn. It took a lot of practice before I trusted constructivism beyond my intellectual agreement and changed my teaching accordingly.

I had a similar, although less grueling, experience in trying to implement social constructivist ideas. My main connection to social constructivism was the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) of Lev Vygotsky. It made sense to me that learners have a zone in which they can develop new ideas based on where they are starting with their knowledge and understanding. When they acquire new knowledge, their whole zone of development moves up. To me, this model represented the ideas that every learner can grow in understanding and that the process of learning is continuous as the learner builds knowledge and expertise.

What I loved the most about the ZPD, though, was the idea that learners cannot reach the highest level of their zone without support and provocation from others (thus the social aspect of constructivism). The idea that learners needed both support and provocation was an epiphany for me. I had always regarded my role as a librarian to be unequivocal support. I did not give idle compliments, but I found a way to support every decision that the students made. I congratulated them for finding a resource, even though I knew that the student could have found much more relevant and credible resources. After my ZPD insight, I started offering both supportive and challenging feedback. I started asking tough questions designed to challenge the students to think harder. I invited students to push beyond their safe boundaries and assured them I would provide support when needed. In other words, Lev Vygotsky provoked me into changing my practice and moving my own zone of development to a higher plane. The students benefited tremendously.

One of the principles of constructivism particularly intrigued me in my role as an instructional leader in the school: “Structuring learning around primary concepts: The quest of essence.” I began to develop and deliver professional development for fellow librarians and teachers on concept-based teaching. This represented a total rethinking in most curricula because it would require reorganization around larger themes. I understood the deep understanding that students would gain from that approach, but I must admit that convincing others was a hard sell.

I still remember one school-wide professional development session on concept-based teaching when some grade level groups immediately started identifying essential concepts and redesigning their curriculums, but the first-grade group did not have a clue. I went to their table to get them started and asked, “What is the first think you teach every year?” “We teach fall.” “What do you want your students to learn about fall?” “Well, you know, we do fall things like color leaves and make applesauce.” “But what do you want them to learn about fall?” Silence. Then one of the teachers burst out, “Oh, change. We want them to learn about change – how animals have to change to adapt to colder weather, and leaves change color, and the weather changes. We want them to learn about why and how things in nature change in the fall.” All of a sudden, every teacher in the room was energized and enthusiastic about identifying larger concepts to frame their curriculum.

Constructivist teaching is largely implemented by putting the learner in charge of his own learning and thinking, but I have learned that it is only successful when the experience is carefully framed by the teacher.

Inquiry Model and Stance

Gradually, I began to rethink my approach to teaching research. My former research-process model no longer matched my philosophy of teaching and learning. I needed to develop a model that synthesized the research I had read and the teaching experiences I had had.

The model that I developed, not so cleverly called the Stripling Model of Inquiry, has six recursive phases of thought and action (Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express, Reflect). Although at this point, I cannot trace all of the contributory ideas behind each phase, some connections are immediately apparent:

- Connect – Connect to self and previous knowledge; gain background and context (Dewey, authentic learning, constructivism)

- Wonder – Develop questions; make predictions, hypotheses (authentic learning, critical thinking)

- Investigate – Find and evaluate information to answer questions, test hypotheses; think about information to illuminate new questions and hypotheses (critical thinking skills, teaching for understanding, constructivism, social constructivism)

- Construct – Construct new understandings connected to previous knowledge; draw conclusions about questions and hypotheses (critical thinking skills, teaching for understanding, constructivism, social constructivism, authentic assessment)

- Express – Apply understandings to a new context, new situation; express new ideas to share learning with others (critical thinking skills, social constructivism, authentic assessment)

- Reflect – Reflect on own learning; ask new questions (critical thinking skills, authentic learning)

I first published my model of inquiry in 2003, in Curriculum Connections Through the Library, a volume that I co-edited with Sandra Hughes-Hassell (Stripling and Hughes-Hassell, 2003). In the first chapter in that edited volume, I tried to capture my thinking about inquiry-based learning. At the time, I was most interested in exploring two aspects of inquiry: 1) differentiating inquiry from information problem-solving and 2) correlating the inquiry skills and strategies with the literacy skills and strategies and the teaching strategies most appropriate for each phase of inquiry.

I have continued to probe the concept of inquiry, both as a framework for learning and as a continuum of skills that must be taught explicitly to all students. Changes in the world of information and technology, the increasing diversity of our students, and the imperative to empower students to be critical consumers and creators of information have influenced the evolution of my ideas. The online publication of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (ESIFC) in 2019 (https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc) reflects my vision of the information fluency standards and skills that will “empower students to develop confidence and agency to pursue their own paths to personal and academic success.”

The four standards of the ESIFC encompass a broad and comprehensive approach to preK-12 learning that is framed by an inquiry stance and student empowerment.

- Standard 1: Inquiry and Design Thinking: Use Inquiry and Design Thinking to Build Understanding and Create New Knowledge

- Standard 2: Multiple Literacies: Use Multiple Literacies to Explore, Learn, and Express Ideas

- Standard 3: Social and Civic Responsibility: Demonstrate Civic Responsibility, Respect for Diverse Perspectives, Collaboration, and Digital Citizenship

- Standard 4: Personal Growth and Agency: Engage in Personal Exploration, social and Emotional Growth, Independent Reading and Learning, and Personal Agency

The 2019 ESIFC represents a culminating (although not final) synthesis of many of the key concepts about teaching and learning that I have developed during my career as a school library professional. A close examination of the continuum of skills will reveal the roots of my educational practice in Dewey, critical thinking, authentic learning and assessment, teaching for understanding, constructivism, and social constructivism. The ESIFC also incorporates skills required by new and developing trends in education, including design thinking, multiple literacies, personalization, digital literacy, social media, social responsibility, social and emotional skills and attitudes, and student voice and agency. All of these areas deserve continued and thorough exploration in terms of their impact on student learning and library instruction.

Literacy and Inquiry in the Digital Environment

Over the last number of years, I have increasingly focused on the inquiry and literacy skills required for students to access and make sense of information in the digital environment. I realized that, although many of the sense-making skills that worked for print materials still applied, characteristics of the digital environment made the teaching of new thinking skills necessary.

The research that I conducted for my doctoral thesis in 2010-2011 identified a number of positive attributes of the digital environment, including wider distribution of knowledge, increased access to information, interactivity, and increased opportunity for students to share their voices beyond school. As I thought about those positive characteristics and opportunities, I realized that the challenge would be in helping students develop new skills to take advantage of those characteristics. For example, wide distribution of knowledge means that students must be able to authenticate, evaluate, and select the most relevant and credible information from the overwhelming pool of information that varies widely in its authoritativeness, quality, level of bias, and purpose.

I decided to probe deeply into the literacy and inquiry skills required by the digital environment. Several authors and researchers were important to the development of my thinking in this area, including Sam Wineburg and the Stanford History Education Group (historical inquiry), J. K. Lee (evaluating digital resources), and van Drie and van Boxtel (historical reasoning). Some of the new or newly essential digital literacy and inquiry skills that I discovered included:

- Constructing effective search strategies (limiting the search to essential and relevant resources, but also broadening the search to include multiple perspectives and alternative viewpoints)

- Contextualization of information (making sense of the information in the context of broad concepts, overview, time, place, point of view)

- Maintaining focus (pursuing a line of inquiry without succumbing to distractions)

- Sourcing (evaluating the authority and credibility of sources)

- Evaluating quality of information (using evaluation criteria appropriate for both fact-based and opinion-based information and being able to differentiate between fact and opinion)

- Lateral reading and corroboration (validating information by comparing it to other sources)

- Deep reading (pursuing in-depth information rather than several sources of surface information)

- Visual literacy (selecting, gathering information from, and interpreting visuals while avoiding “graphic seduction”)

- Media literacy (evaluating and interpreting media messages based on their accuracy, purpose, and bias)

The final area in the realm of digital inquiry that I have been exploring is social responsibility, which includes the complexities and responsibilities inherent in social media, civic responsibility, and digital citizenship. The burgeoning use of social media makes this aspect of digital inquiry especially troublesome. Adults and students alike struggle to resist virality, misinformation, cyberbullying, and intentional misinformation. Social media have empowered students to produce and publish information and opinions, but the skills needed for responsible interactivity must be identified and explicitly taught. Social interactivity/responsibility is probably the area of digital inquiry that is most connected to students’ lives outside of school and least connected to the skills that are actually taught in school.

Dispositions, Social-Emotional Growth, Empathy, Agency and Voice

At the same time that I have been exploring digital literacy and inquiry, I have been investigating the social and emotional aspects of learning. I recognize the importance of motivation, attitudes, and emotions in the learning process. I also realize that I have been neglecting those aspects of learning in my focus on cognitive development.

The first time I seriously considered the emotional aspects of research or inquiry was in 2004 when I read Seeking Meaning: A Process Approach to Library and Information Services by Carol Kuhlthau. In Seeking Meaning, Kuhlthau presented her research process model, the Information Search Process (ISP). I had already developed my inquiry model at that point and I recognized many similarities and a couple of significant differences in our models. But what was ground-breaking for me was that Kuhlthau provoked my thinking about the affective aspects of student research by identifying the feelings that students experienced as they were conducting research.

In 2006-2008, I had the privilege of serving on the American Association of School Librarians (AASL) Learning Standards Task Force. We developed a set of standards for the 21st-century learner and a standards-in-action publication (Standards for the 21st-Century Learner in Action) that identified essential skills, but also broadened the scope to include dispositions, responsibilities, and self-assessment strategies (AASL, 2009). The dispositions were aligned with each of the four standards and included attitudes like initiative, confidence, persistence, emotional resilience, flexibility, critical stance, leadership, social responsibility, curiosity, motivation, and openness to new ideas. Through that work, I expanded my own understanding of the dispositions that librarians could foster and assess while their students were engaged in library experiences.

My next deep foray into the social and emotional aspects of learning occurred in 2010-2011 when I focused my doctoral research on primary sources and the development of empathy. I found that empathy requires contextualization and is fostered by paying attention to multiple perspectives.

I recognized that the teaching of empathy and perspective-taking was ever more important given the ready access to primary-source information about global events and limited access to unbiased contextualization. I began integrating attitudes into the continuum of information fluency skills that my colleagues and I were developing in New York City (the first version of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum published in 2009).

The imperative that librarians take responsibility for fostering social and emotional skills and attitudes came into critical focus for me during the Arab Spring protests in 2010 when I realized that I and others were making assumptions and judgments based on emotional tweets and biased information. The increasing level of interactions on social media that are emotional rather than rational have propelled me to dive more deeply into the social and emotional aspects of learning.

The most valuable model of social/emotional learning for me is the SEL Framework developed by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). All five areas of competence in the SEL Framework (self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making) are applicable to the development of information fluency. In the 2019 ESIFC, I identified skills in each of these areas of competence that librarians could incorporate into their instructional curriculum. For example, pre-kindergartners are expected to identify their own feelings and share them with others when appropriate [self-awareness]. Grade 4 students are expected to identify and respect cultural differences and diverse opinions [social awareness]. A benchmark skill for grade 6 is “Builds trusting relationship with diverse peers and adults through collaboration and communication [relationship skills].” Students in high school are expected to demonstrate self-management through this competence: “Demonstrates commitment and perseverance by pursuing academic and personal learning until a goal is attained.”

The final aspect of my current exploration of social and emotional learning concerns agency and voice. This focus represents a shift in my thinking about the goal of school library instruction. My goal has always been to empower young people to be independent learners and thinkers. Now, I have a higher goal – to enable young people to develop the agency and voice to express their ideas and thoughts with confidence and competence. I have researched the concept of agency and have started to articulate how students (and librarians) can develop their own agency through the competencies delineated in the information fluency continuum (ESIFC). I will continue to explore the concept of agency and its implications for taking social action within and beyond the boundaries of the school.

The Journey Continues

The beauty of an epistemology about learning and inquiry is that the very nature of inquiry demands continuous learning. I will never have inquiry all figured out, but I am grateful to Darryl Toerien and the FOSIL Group for inviting me to continue the conversation. Every new understanding that we gain is a building block for future learning and more effective teaching and learning through the school library.

References

- AASL. (2009). Standards for the 21st-Century Learner in Action. Chicago: AASL.

- Berman, S. (1991). Thinking in context: Teaching for openmindedness and critical understanding. In Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking, Revised Edition, Vol. 1, A. L. Costa (ed.), 10-16. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Brooks, J. G., and M. G. Brooks. (1993). The Case for Constructivist Classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Costa, A. L., ed. (1991). Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking, Revised Edition, Vol. 1. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Education. NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Francis, E. (May 9, 2017). What Is Depth of Knowledge? ASCD Inservice. https://inservice.ascd.org/what-exactly-is-depth-of-knowledge-hint-its-not-a-wheel/.

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (2004). Seeking Meaning: A Process Approach to Library and Information Services, 2nd Edition. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Marzano, R. J., and D. E. Arredondo. (1986). Tactics for Thinking: Teacher’s Manual. Aurora, CO: Mid-continent Regional Educational Laboratory.

- Newmann, F. M., W. G. Secada, and G. G. Wehlage. (1995). A Guide to Authentic Instruction and Assessment: Vision, Standards and Scoring. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

- Olson, C. B. (1991). The thinking/writing connection. In Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking, Revised Edition, Vol. 1, A. L. Costa (ed.), 147-152. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Paul, R. W. (1991). Teaching critical thinking in the strong sense. In Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking, Revised Edition, Vol. 1, A. L. Costa (ed.), 77-84. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Stripling, B. K., and J. M. Pitts. (1988). Brainstorms and Blueprints: Teaching Library Research as a Thinking Process. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

- Stripling, B. K. (2003). Inquiry-based learning. In Curriculum Connections Through the Library, B. K. Stripling and S. Hughes-Hassell (eds.), 3-39. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Stripling, B. K. (2019). Empire State Information Fluency Continuum. https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc.

- Webb, N. (2002). Depth of Knowledge Levels for Four Content Areas. http://ossucurr.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/49691156/Norm%20web%20dok%20by%20subject%20area.pdf.

- Wiggins, G., and J. McTighe. (1998). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Login | Register or fill out the form below to comment as a guest