E&L Memo 0 | Developing inquiring minds: a journey from information through knowledge to understanding

Darryl Toerien | April 11, 2019

UncategorisedThis article was originally published in School Libraries in View (Issue 44) and is meant to serve as an introduction to and overview of the FOSIL Cycle.

(Re)Purposing the School Library

Dallas Willard (2014), long-time Professor of Philosophy at The University of Southern California in Los Angeles, claimed that there are four fundamental questions that all human beings ultimately have to answer, of which the answers to the first two concern us here:

- What is reality? Reality is what you have to deal with.

- What is success? Success is how well you deal with reality.

Now, it is an educational reality that, as Seymour Papert[1] is widely reported to have put it, you can’t teach people everything they need to know, so the best you can do is position them where they can find what they need to know when they need to know it. It is, furthermore, an educational reality that many schools seem unwilling or unable to deal with, and this has grave implications for not only the students.

Our efforts to deal with this educational reality resulted in FOSIL (Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning).

FOSIL grew out of our deeply held conviction, expressed so simply and so powerfully by Danny Hillis (2004), that we ought to be able to learn anything by finding out for ourselves. Now Danny Hillis is one of the smartest people on the planet, so he knows a thing or two about learning for oneself. In making this claim, he was addressing one of the four conditions necessary for this to happen – information, and specifically the right information in a building maelstrom of information. The other three conditions are the desire, or at least the willingness, to learn for ourselves, an understanding of the processes by which we learn for ourselves, and growing mastery of the skills that enable these processes.

These conditions, or more precisely these conditions in combination, do not occur naturally in school, and if they occur at all, it is by design. FOSIL, then, is learning to learn anything for ourselves by design.

FOSIL and the desire to learn by finding out for ourselves.

This goes to the heart of the matter, because what we truly value is revealed by what we make time for. It takes time to learn to learn for ourselves, and it is difficult. As a consequence, the condition in which the expectation that we learn for ourselves gives rise to the willingness to learn for ourselves, which in turn gives rise to the desire to learn for ourselves, does not exist in many schools. Once it does, an understanding of the processes by which we learn for ourselves becomes necessary.

FOSIL and the processes by which we learn for ourselves.

On one level, FOSIL is a model of the inquiry process that is simple to understand and apply. As is often the case, some of our simplest tools are also our most powerful, and this is the case with FOSIL: Year 6 students used it to carry out a closed inquiry into reasons for the ‘greatness’ of Alfred the Great, while, at the same time, a student in Year 12 was using it to carry out an open inquiry into the causes of the underrepresentation of women in computer science, for which she won Best Research Project in the 2018 TeenTech Awards.

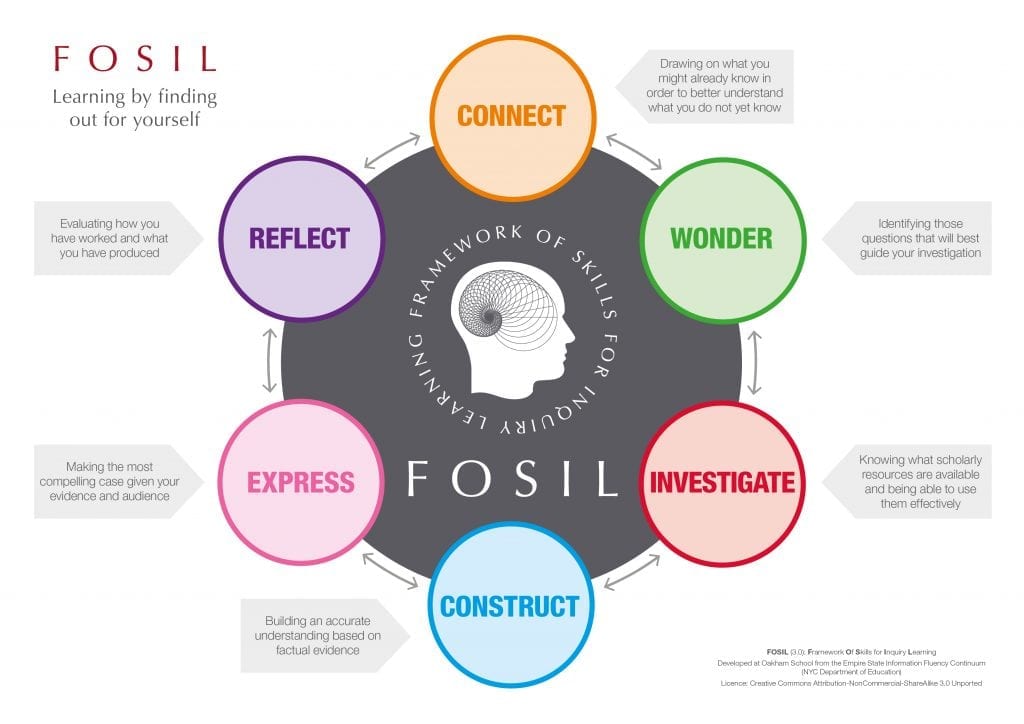

Stages in the FOSIL Inquiry Cycle.

The simplicity, and power, of FOSIL lies in the logical way the stages in the inquiry process interrelate.

Figure 1: The FOSIL Cycle (3.0)

- Connect: Knowledge builds on knowledge, so pausing to take stock of what you already know reveals more clearly what you do not yet know.

- Wonder: Gaps in what you know give rise to questions, some more fruitful than others.

- Investigate: These questions guide your investigation, which is aimed at sourcing reliable information that you can work with.

- Construct: This is the point of learning by finding out for yourself – building knowledge and understanding from information in response to the questions that you have.

- Express: Once you know what you are talking about, you need to be able to share it appropriately, effectively and ethically.

- Reflect: Doug Engelbart said it best when he said that the better we get at getting better, the faster we will get better(Computer History Museum, 2018).

FOSIL and mastering the skills that enable the processes by which we learn for ourselves.

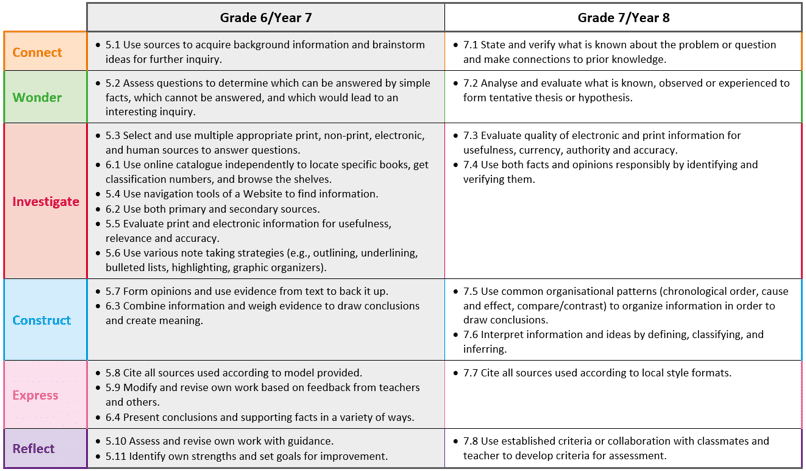

On another level, FOSIL is also the specific and measurable skills that enable each of the stages in the Cycle, and these skills develop over the time that a student is at school. For example, the ability to create a list of all the sources used in a bibliography becomes the ability to cite and reference each of the sources used.

Figure 2 The FOSIL Framework of Priority Benchmark Skills for Years 7 & 8 (the framework covers Year 1 – Year 13)

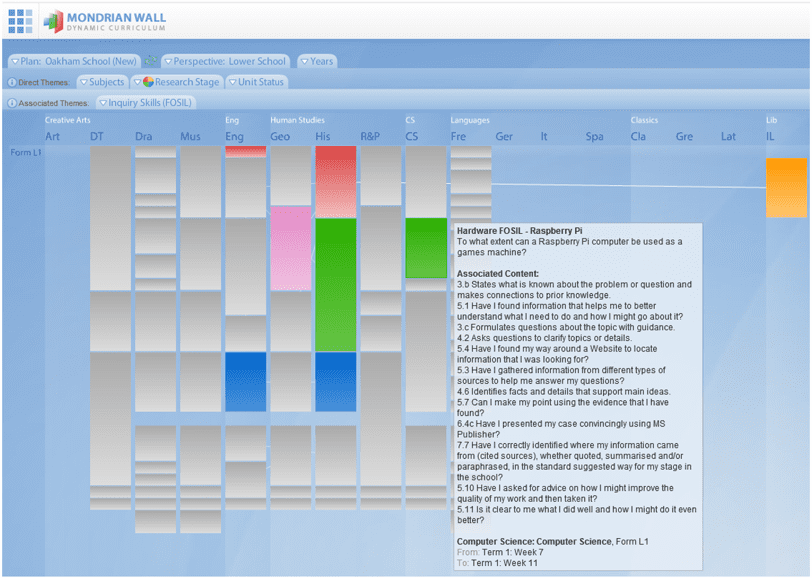

These skills need to be taught and practised in and across all academic disciplines if they are to be mastered, and this cannot be left to chance. Consequently, we have invested in Mondrian Wall, which is a powerful technology that enables us to map the progression of these skills against the taught curriculum.

Figure 3 Mondrian Wall software showing units with associated FOSIL skills in Year 6

FOSIL and the information needed to construct knowledge and build understanding for ourselves.

The problem with sourcing reliable information used to be that it was difficult to find because information was scarce. This was primarily a problem of access. Sourcing reliable information is still difficult, but this is because information is overwhelmingly abundant. This is primarily a problem of discernment. FOSIL addresses this problem in two ways. Firstly, it directs students towards a rich collection of age-appropriate scholarly resources, both print and online, which allows them, initially, to focus on developing their mastery of the processes and skills of inquiry. Secondly, the skills that enable Investigate and Construct include, for example, the effective use of internet search engines to find information and the critical use of web-based information.

The role of the Library

Creating and maintaining the combination of conditions outlined above is a complex task. In countries with a long history of learning through inquiry, librarians and teachers work together as an instructional team. It soon becomes obvious why. Teachers, clearly, are specialists in their academic discipline, who ought to have up-to-date knowledge of developments within their discipline. Librarians are information specialists, who ought to have a concern with how information becomes a coherent body of interdisciplinary knowledge, which is reflected in the library’s collection. Because learning to learn for ourselves needs to be taught, and supported, the focus of collaboration between teachers and librarians is threefold:

- Designing a good inquiry, which requires an understanding of the type of inquiry that is appropriate – closed, guided or open.

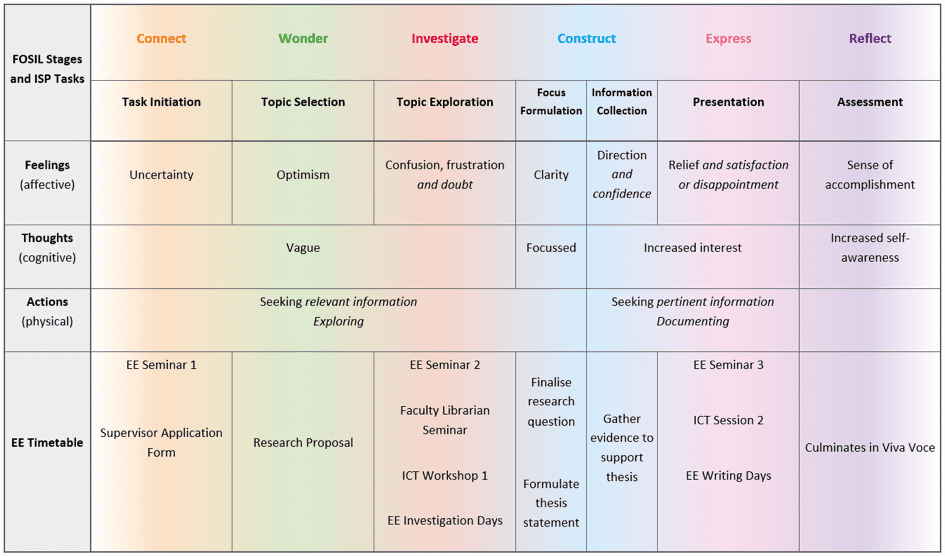

- Supporting the inquiry, which requires an understanding of the stages involved in inquiry – including the affective, cognitive and physical demands that inquiry makes of students.

- Resourcing the inquiry, which goes beyond age-appropriate information to include time and resources to help students manage the inquiry process.

Knowledge or skills?

This is a false dichotomy that arises out of a poor understanding of learning through inquiry and/or a poor experience of learning through inquiry. In both cases, this is almost certainly due to a combination of a poorly designed and supported inquiry combined with students who have not have been equipped for inquiry. In countries with a long history of learning through inquiry, a properly designed and supported inquiry is a powerful way to gain knowledge.

Where does FOSIL come from?

FOSIL is based on the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (New York State Education Department, 2014), developed by the New York City School Library System under the direction of Barbara Stripling. The New York City school district is the largest in the United States, with more than 1.1 million students in over 1,800 schools. Barbara Stripling, now Senior Associate Dean of the iSchool at Syracuse University, is one of the pioneers of learning through inquiry. Another major influence on the development of FOSIL is Carol Kuhlthau, now Distinguished Professor Emerita of Library and Information Science at Rutgers University, whose ground-breaking work on describing the affective, cognitive and physical demands that inquiry makes of students adds a vital dimension to FOSIL.

Figure 4 Our first attempt to combine insights from Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process (Kuhlthau, 2004, p. 82) with FOSIL to inform our Extended Essay Timetable

What is in a name?

FOSIL stands for Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning. The fact that it sounds like FOSSIL is deliberate. Firstly, the discipline of archaeology is a helpful way to think about inquiry. Secondly, it serves as a warning against complacency, because a framework, or progression, of inquiry skills must evolve in response to changes in the environment if it is to remain vital.

The Evolution of FOSIL

FOSIL is evolving in two ways. Firstly, we are building a deep understanding of learning through inquiry, so while we have already come a long way on our journey, we still have a way to go. This means that FOSIL is a collaborative work in progress. Secondly, and following on from the first, FOSIL is at the centre of a growing community of schools who are on a similar journey. To this end, we are in the process of establishing a FOSIL Group, the purpose of which is to provide a forum for active collaboration on developing a culture and practice of learning though inquiry that is focused on but not limited to FOSIL.

Postscript or Epitaph

To return to the grave consequences of a collective failure to effectively position students where they can find what they need to know when they need to know it, whether through inaction or inability, brings me to the title of this article.

Since changing my profession from teaching to school librarianship in 2003, two questions have haunted me:

- Why is the school library, and particularly the secondary school library[2], peripheral to teaching and learning, if it features at all, even in schools with relatively well-resourced libraries?

- How, then, does one justify the existence of the school library, and particularly the secondary school library?

Fifteen years later, while preparing for a presentation on learning through inquiry at the 2018 SLG National Conference, I was directed by two unrelated sources to Simon Sinek’s contention that people do not buy into what you do (your mission), but why you do it (your purpose), and that while most purpose-driven leaders can articulate their mission, many mission-driven leaders cannot articulate their purpose (2009). This finally provided the impetus and opportunity for me to articulate as clearly as possible the purpose and mission of the library that I had been entrusted with, which required me to satisfactorily answer the two questions that had been haunting me.

The purpose of the Smallbone Library, which is the reason why it exists, is to enable our students to say with assurance, “the world belongs to me because I understand it” (Honoré de Balzac in the words of Saul Bellow (1987, p. 15)).

Our mission is to do this by, first and foremost, developing capacity for informational reading, by which we mean primarily reading for FOSIL-based inquiry learning, and then recreational reading, by which we mean primarily our Reading Journey.

Observations on this purpose and mission:

- This purpose of the library is, I would argue, the same as the fundamental purpose of the school (Oakham School, 2018), which ought to be obvious, but surprisingly isn’t. This, in turn, positions us to explain our unique and crucial contribution to this shared purpose.

- Positively, this means that the world and the fullness of its possibilities are open to me to the extent that I understand how it works. Negatively, this means that I am at the mercy of those who would take advantage of me to the extent that I don’t understand how the world works – if I am lucky, I may lose some money; if not, then I stand to lose a great deal more.

- Our unique and crucial contribution to this shared purpose is developing capacity for reading. However, I am increasingly convinced that, for the secondary school library at least, developing capacity for informational reading[3] takes precedence over recreational reading[4]. At the risk of oversimplifying, the reason for this is twofold:

- As students progress through school, the amount of informational reading that they are required to do increases even as the amount of timetabled time that they have available for recreational reading decreases. This seems like a natural progression to me, and for us, FOSIL has become the primary tool for developing capacity for informational reading.

- I am beginning to suspect that much of the formative development with regard to recreational reading has already taken place before our students get to us, shaped by primary school and, more significantly, home[5]. While we need to nurture what we get, we also need to be realistic about what we can achieve with the time that we have, which is primarily those timetabled lessons that make up our Reading Journey for Years 6–9[6].

- I would argue, then, that interdisciplinary informational reading[7] (nonfiction for simplicity’s sake) and recreational reading (fiction for simplicity’s sake) together provide the fullest understanding of our world and the way that it works. While this repurposed approach to reading does not guarantee the existence of the library, explicitly tying the purpose of the library to that of the school and then clearly articulating the library’s unique and crucial contribution to that shared purpose in these terms, has resulted in a library that is no longer peripheral to teaching and learning, but integral.

As I said at the outset, FOSIL is our evolving response – almost a decade in the making – to an educational reality that increasingly requires students to be able to learn for themselves. This, in turn, required us to confront our lack of clarity about why what we do actually matters, as well as exactly what it is that we then do. Time will ultimately determine how successfully we have dealt with reality, but in the meantime, we’re getting better at better equipping our students to deal with theirs.

[1] Seymour Papert, Professor Emeritus at the MIT Media Lab, is not the only, or first, or even the last person to describe this educational reality, but he was uniquely positioned to do so – L. Rafael Reif, President of MIT, said of Seymour Papert following his death in 2016 that he “helped revolutionize at least 3 fields, from the study of how children make sense of the world, to the development of artificial intelligence, to the unique intersection of technology and learning” (MIT Media Lab, 2016).

[2] The secondary school library has been my particular concern simply because I have always worked in a secondary school library.

[3] “Informational text is a type of nonfiction…the primary purpose [of which] is to convey information about the natural or social world” (Duke & Bennett-Armistead, 2003, p. 16).

[4] We have chosen to refer to reading that is not informational as recreational reading rather than reading for pleasure. The main reason for this is simply that not all students find reading pleasurable, and many, despite our best efforts, never will; however, we can provide opportunities for recreational reading, if by recreational we mean for purposes other than work, some of which may be pleasurable.

[5] My suspicion may be incorrect, and this is an aspect of our work that we need to investigate with some urgency.

[6] This equates to one 50-minute lesson every week for Years 6 and 7, and one 50-minute lesson every two weeks for Years 8 and 9.

[7] Clearly, if we are trying to make sense of the world through informational reading, then we need to view subjects, or disciplines, as perspectives on the world, or ways of understanding how it works. Furthermore, these perspectives must contribute to a coherent body of knowledge, which, for us in the library, must be reflected in our collection, both print and online, which, in turn, must be accessible to students at each stage in their journey through the school.

Bibliography

Bellow, S. (1987). Foreword. In A. Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (pp. 11-18). New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Computer History Museum. (2018). Hall of Fellows: Douglas C. Engelbart. 2005 Fellow. Retrieved from Computer History Museum: http://www.computerhistory.org/fellowawards/hall/douglas-c-engelbart/

Duke, N., & Bennett-Armistead, V. (2003). Reading and Writing Informational Text in the Primary Grades: Research Based Practices. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Hillis, W. D. (2004, June 5). “Aristotle” (the Knowledge Web). Retrieved from Egde: https://www.edge.org/conversation/w_daniel_hillis-aristotle-the-knowledge-web

Kuhlthau, C. C. (2004). Seeking Meaning: A Process Approach to Library and Information Services (2nd ed.). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

MIT Media Lab. (2016, August 1). Professor Emeritus Seymour Papert, Pioneer of Constructionist Learning, Dies at 88. Retrieved from MIT CSAIL: https://www.csail.mit.edu/news/professor-emeritus-seymour-papert-pioneer-constructionist-learning-dies-88

New York State Education Department. (2014, July 11). Empire State Information Fluency Continuum. Retrieved from EngageNY: https://www.engageny.org/resource/empire-state-information-fluency-continuum

Oakham School. (2018). Learning at Oakham. Retrieved from Oakham School: https://www.oakham.rutland.sch.uk/Learning-at-Oakham

Sinek, S. (2009, September). How Great Leaders Inspire Action. Retrieved from TED: https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action

Willard, D. (2014). The Divine Conspiracy. London: William Collins.

Login | Register or fill out the form below to comment as a guest