Article | School Libraries in View

Tags: ArticleFebruary 1, 2023

FOSIL Group member Darryl Toerien contributed an article to School Libraries in View (Issue 47, January 2023), the annual Journal of the CILIP School Libraries Group.

—

IFLA and Global Action for School Libraries

“Do not block the way of inquiry.” (Charles Sanders Peirce, 1955)

Darryl Toerien, Head Inquiry-Based Learning at Blanchelande College

—

I was delighted to receive an invitation from Caroline Roche to contribute an article on IFLA and school libraries to this issue of SLIV, for the last year has seen the culmination of two significant and far-reaching developments in this regard.

The first development is the revised IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto (2021), which revitalises the principles upholding the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015). After extensive and widespread international consultation, the revised Manifesto – as jointly agreed by the Chair on behalf of the IFLA School Libraries Section (IFLA SLS) and the President on behalf of the International Association of School Librarianship (IASL) – has been submitted by IFLA to UNESCO for endorsement, and we eagerly look forward to being able to reference this document in its final form. It is worth noting that the Guidelines were also reviewed, and it was agreed that they are not yet due for revision.

The second development is the publication of the latest book in the IFLA/De Gruyter Global Action for School Libraries series, Models of Inquiry (Schultz-Jones & Oberg, 2022), which reaffirms the centrality of inquiry to achieving the school library’s educational and moral purpose. This book was launched jointly at the IASL 2022 Conference and Research Forum and the IFLA SLS Satellite Meeting ahead of the IFLA 2022 World Library and Information Congress. Although I was not able to attend the IASL book launch, I was able to present my chapter on FOSIL – FOSIL: Developing and Extending the Stripling Model of Inquiry – at the IFLA SLS Satellite Meeting, and Jenny Toerien was able to present her chapter – FOSIL: Deep Collaboration by Teacher and Librarian to Develop an Inquiry Mindset – that she co-authored with Joe Sanders from Oakham School. Both presentations can be downloaded from here on the FOSIL Group website (Jenny and Joe jointly delivered an inspiring presentation on their chapter at the IFLA SLS 2022 Midyear Meeting, which can be viewed here on YouTube).

I include the book overview from the publisher’s website below for reasons that I will return to later:

This book focuses on inquiry-based teaching, one of the five vital aspects of the instructional work of school librarians identified in the second edition of the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015). Effective implementation of inquiry-based teaching and learning requires a consistent instructional approach, based on a model of inquiry that is built upon foundations of research and best practice.

The book explains the importance and significance of inquiry as a process of learning; outlines the research underpinning this process of learning; describes ways in which models of inquiry have been developed; provides recommendations for implementing the use of such models; and demonstrates how the other core instructional activities of school librarians, such as literacy and reading promotion, media and information literacy instruction, technology integration and professional development of teachers, can be integrated into inquiry.

Inquiry-based learning is part of “learning to be a learner,” a lifelong pursuit involving finding and using information. Inquiry develops the skills and understandings that learners need in new information environments, whether that be as students in post-secondary institutions, as producers and creators in workplaces, or as citizens in communities.

Through inquiry-based teaching, school librarians help students to build the essential skills and understandings needed for dealing with complex learning challenges, including analysis, critical thinking, and problem solving. In this book, special attention is given to the development of students’ metacognitive abilities, which are essential to their becoming life-long and life-wide learners.

Following our presentations, I was invited to submit a chapter on FOSIL for an upcoming IFLA/De Gruyter book titled, Libraries Empowering Society through Digital Literacy. As Matthew Syed (2015) observes, insight is the endpoint of a long term, iterative process, and in wrestling with this chapter I reached great insight into the importance and urgency of our calling as school librarians. Because exploring this in any detail is beyond the scope of this article, I share the abstract below, which will bring me back to Models of Inquiry:

Digital Literacy: Necessary but Not Sufficient for Lifelong Learning

This chapter argues that the problem that digital literacy addresses is an epistemological problem, a problem of knowing and coming to know, and so is bigger than digital literacy skills even though knowing and coming to know are increasingly dependent on digital literacy skills. The rupture between knowledge and reality as uncovered by the academic disciplines – reflected in Jean-Francois Lyotard’s, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1984) – has resulted in a more widespread breakdown of the knowledge-building process, which is an inquiry process. Because action conforms to knowledge, or ought to, this epistemological crisis lays the groundwork for an existential crisis, mounting evidence of which is all too obvious. To avert this existential crisis, it is necessary, therefore, to resolve the underlying epistemological crisis, which means developing engaged and empowered inquirers. The most effective way to do this is to make better use of the many years of formal education that school provides. In this, schools can draw on more than 60 years of international research-informed development of inquiry as a highly effective pedagogical strategy for learning disciplinary content in a school setting, which requires collaboration between classroom-based teachers and library-based teachers. Central to this pedagogical strategy is a sound instructional model of the inquiry process and underlying framework of developmentally appropriate inquiry skills, which, crucially, include digital literacy skills. FOSIL, which is based on the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, is such a model and underlying framework of inquiry skills.

My concern here is not with FOSIL, for FOSIL is but one – two if you count the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum – of the five inquiry models in Models of Inquiry, which is not exhaustive. Rather, my concern here is with school as the vital means of producing the reality-based community of error-seeking inquirers that are responsible for and responsible to the Constitution of Knowledge, which is the epistemological operating system of liberal democracy (Rauch, 2021). For, as Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner (1971) point out, “school, after all, is the one institution in our society that is inflicted on everybody, and what happens in school makes a difference – for good or ill” (p. 12). They then go on to argue that “of all the ’survival strategies’ education has to offer, none is more potent or in greater need of explication than the ‘inquiry environment’” (p. 36). Now, I am in no doubt of the potency of the inquiry environment as a survival strategy. However, I am also in no doubt that the inquiry environment remains in great need of explication, despite the best efforts of colleagues around the world over the last 60 years. For this reason, the publication of Models of Inquiry is a welcome theoretical and practical contribution to the growing body of work explicating the inquiry environment. This, somewhat perplexingly, is in stark contrast to Understanding the impact of inquiry learning: Literature review, which is included in the Great School Libraries Campaign End of Phase 1 Report (2021), and which I feel I must address here for the record.

I say perplexing, because the review is clearly a review of the international literature, and yet contains glaring omissions that weaken the case for inquiry to the extent that I did not feel able to share the Report for the time that it would take to compensate for them. As I do not want this article to become negative, or detract from the laudable achievements of the GSL campaign as reflected in the Report, I will provide a single example that may serve to encourage other colleagues who may have been similarly disappointed.

A simple web search (I used Bing) for “inquiry-based learning literature review” lead immediately to Inquiry-Based Learning: A Review of the Research Literature (Friesen & Scott, 2013), which “draws on theory and research in the field to provide insight into the efficacy of particular approaches to inquiry in terms of their impact on student learning, achievement, and engagement” (from the website summary).

While this particular review is now a little dated, it is more recent than the majority of refences in the GSL review. Not only does this review provide a sound contextual framework for inquiry-based learning, it also, and more importantly, includes Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching, by Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark (2006), which the GSL review includes, as well as the robust response by Hmelo-Silver, Duncan, and Chinn (2006), Scaffolding and Achievement in Problem-Based and Inquiry Learning: A Response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark, which the GSL review does not include. Nothing that I have read by Kirschner, Sweller and/ or Clark since then convinces me that they are actually addressing what we understand inquiry-based learning and teaching to be, including Sweller’s recent Why Inquiry-based Approaches Harm Students’ Learning (2021). Although focused on STEM, but clearly not limited to it, for a balanced and helpful discussion of the main issues involved in this particular debate, see Inquiry vs direct teaching for interdisciplinary STEM (Tytler, 2019), especially the concluding paragraph:

Direct teaching advocates the gradual ceding of control to students after they have been taught techniques, and monitoring of their work, rather than our staged process of exploration, invention, evaluation and revision. The payoff, we argue, is that students come to know the disciplinary ideas in richer ways. We have found, however, that the approach requires of teachers both significant knowledge of the science and mathematics, and command of a pedagogy involving negotiation and refinement of student ideas, compared to ‘telling’. It also takes more time. However, if we are serious about developing STEM skills for interdisciplinary problem solving, we argue there are no shortcuts.

More broadly, the McKinsey report, How to improve student educational outcomes: New insights from data analytics (Mourshed, Krawitz, & Dorn, 2017), includes the finding that “students who receive a blend of teacher-directed and inquiry-based instruction have the best outcomes,” which comes as no surprise to us.

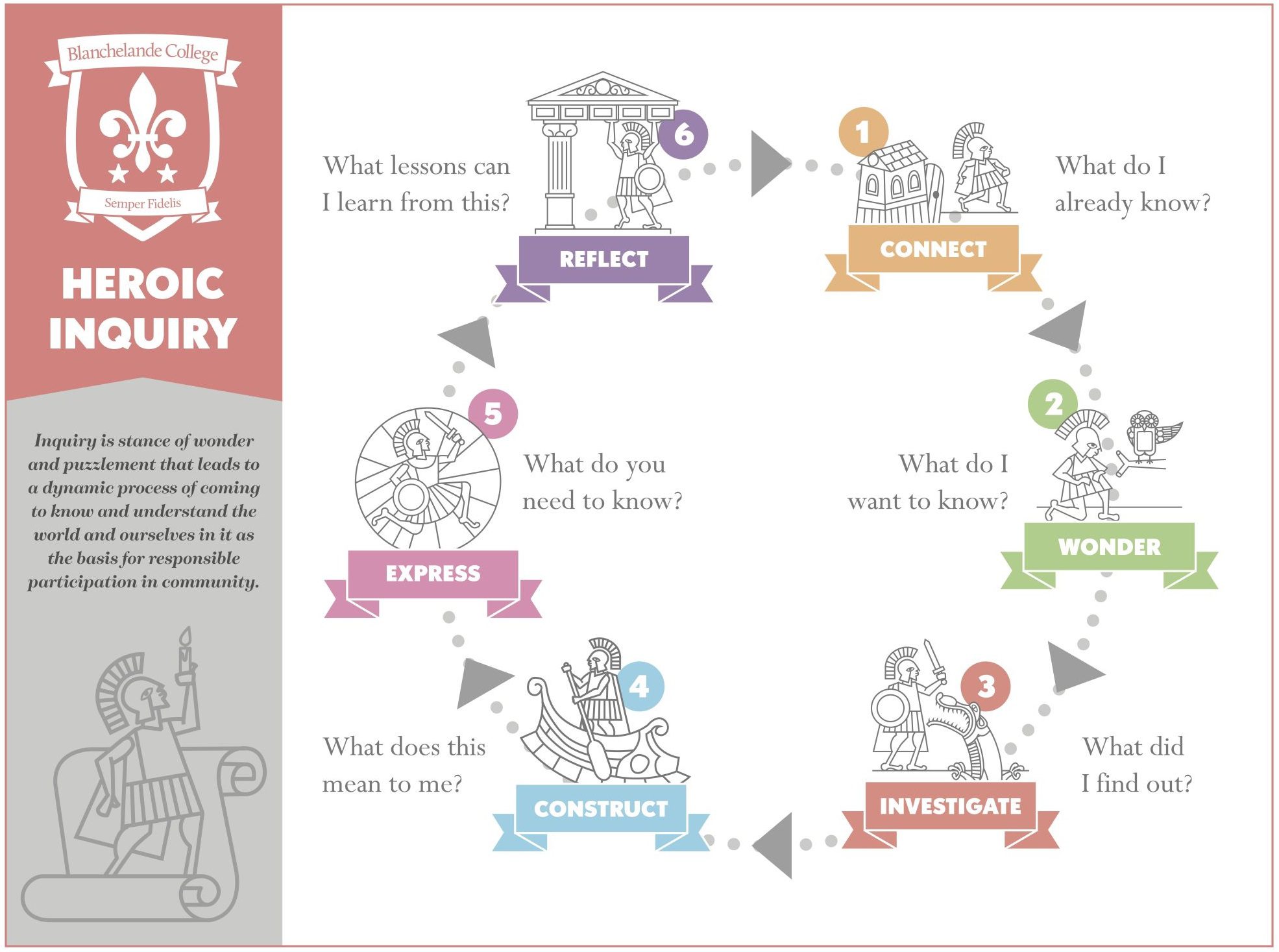

The point that I hope to make here, is that against the relentless attack on the Constitution of Knowledge, upon which our democracy depends, inquiry remains the most potent survival strategy that education can offer society, and which school librarians are, or can be, integral to. However, conditions in schools will always only be more or less favourable to inquiry, and librarians, hence the great and abiding need for explication of the inquiry environment. By way of encouragement, though, I share the following, which now appears in every teaching and learning space in our school, from reception to Year 13, and which offers only GCSEs and A-levels:

In no way does this mean that the need here for explication is over, and I doubt that it ever will be. However, it is a first and vital expression of Charles Sanders Peirce’s corollary upon the first rule of reason (p. 54, emphasis added):

Upon this first, and in one sense this sole, rule of reason – that in order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so desiring not be satisfied with what you already incline to think – there follows one corollary which itself deserves to be inscribed upon every wall of the city of philosophy: Do not block the way of inquiry.

—

Bibliography

- Friesen, S., & Scott, D. (2013). Inquiry-Based Learning: A Review of the Research Literature. Retrieved from Galileo Educational Network: https://galileo.org/focus-on-inquiry-lit-review.pdf

- Great School Libraries. (2021). The Great School Libraries campaign End of Phase 1 Report. Retrieved from Great School Libraries: https://www.greatschoollibraries.org.uk/_files/ugd/8d6dfb_cb4852201e564cf7b555deb009402e56.pdf

- Hmelo-Silver, C., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. (2006). Scaffolding and Achievement in Problem-Based and Inquiry Learning: A Response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark. Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 99-107.

- IFLA School Libraries Section Standing Committee et al. (2015). IFLA School Library Guidelines, 2nd revised edition. The Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Retrieved from Available at https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/58

- Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

- Mourshed, M., Krawitz, M., & Dorn, E. (2017, September 22). How to improve student educational outcomes: New insights from data analytics. Retrieved from McKinsey & Company: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/how-to-improve-student-educational-outcomes-new-insights-from-data-analytics

- Peirce, C. S. (1955). The Scientific Attitude and Fallibilism. In J. Buchler (Ed.), Philosophical Writings of Peirce(pp. 42-59). New York, NY: Dover Publications.

- Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. (1971). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Rauch, J. (2021). The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defence of Truth. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Schultz-Jones, B. A., & Oberg, D. (Eds.). (2022). Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

- Sweller, J. (2021). Why Inquiry Based Approaches Harm Students’ Learning. Sydney: The Centre for Independent Studies.

- Syed, M. (2015, November 14). Viewpoint: How creativity is helped by failure. Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-34775411?CMP=%3FSThisFB

- Tytler, R. (2019, August 9). Inquiry vs direct teaching for interdisciplinary STEM. Retrieved from STEME: Science Technology Engineering Mathematics and Environmental Education Research Group: https://deakinsteme.org/blog/inquiry-vs-direct-teaching-for-interdisciplinary-stem/

Login | Register or fill out the form below to comment as a guest