Reply To: Reading for Inquiry Learning

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Reading for Inquiry Learning › Reply To: Reading for Inquiry Learning

I recognize the importance of teaching deep reading skills as a part of inquiry, but I also know the power of enabling the development of deep reading whenever and whatever our students are reading – from stories to websites to personal explorations to inquiry. As a part my work in 2018 to develop a PK-12 information fluency continuum (adopted throughout New York State and called the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum – ESIFC) (https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc), I created a large body of graphic organizers to guide students’ independent practice for each of the priority skills in the continuum. I have selected a few that I thought would be particularly relevant to the teaching of deep reading skills. Excerpts of those graphic organizers are below, but the full, Word versions can be downloaded free from the above site. I have included the identifying numbers of the graphic organizers for your convenience.

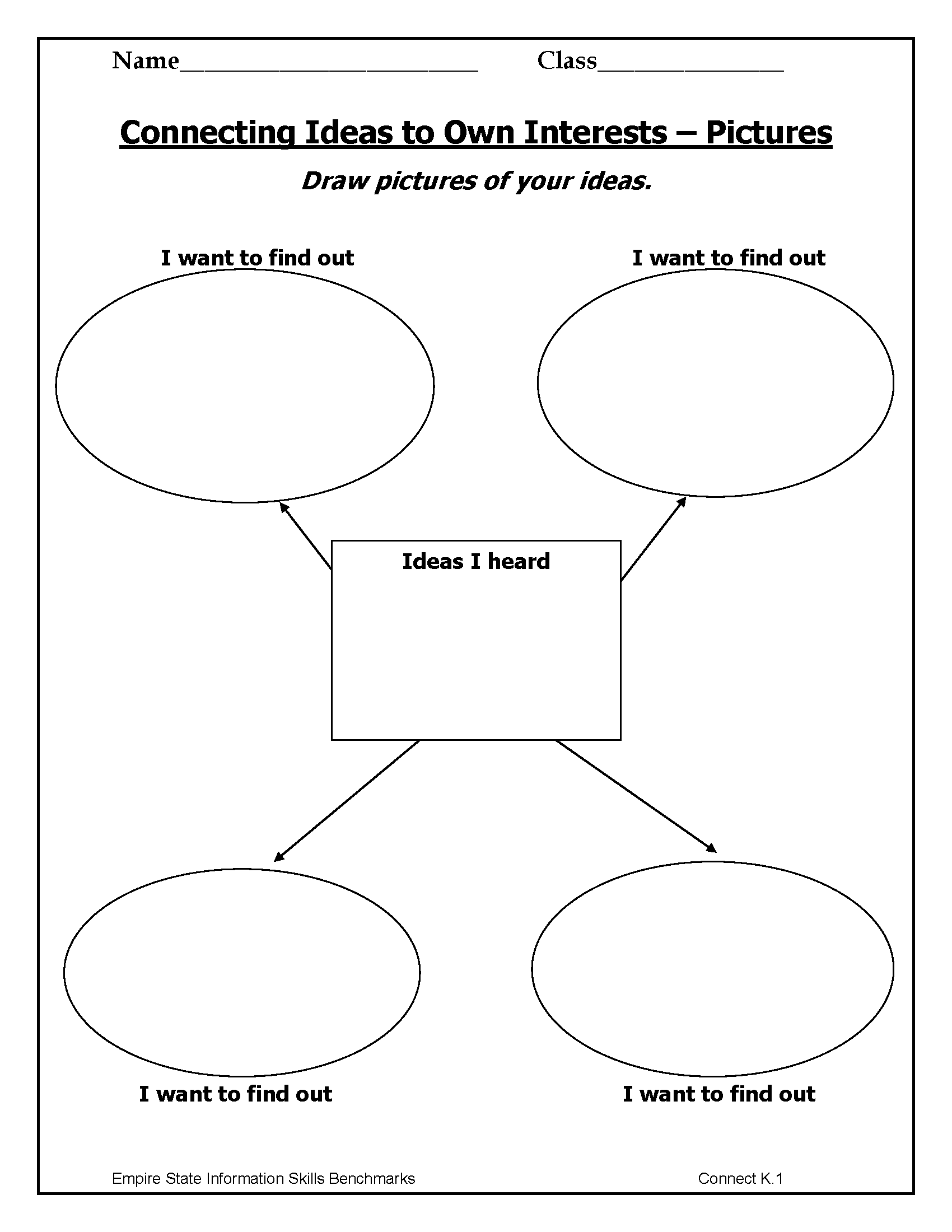

Connect. A foundation of deep reading is the reader’s ability to make connections between the text and his own interests, prior knowledge, and questions. We can start with early elementary children by enabling them to connect ideas to their own interests (K.1).

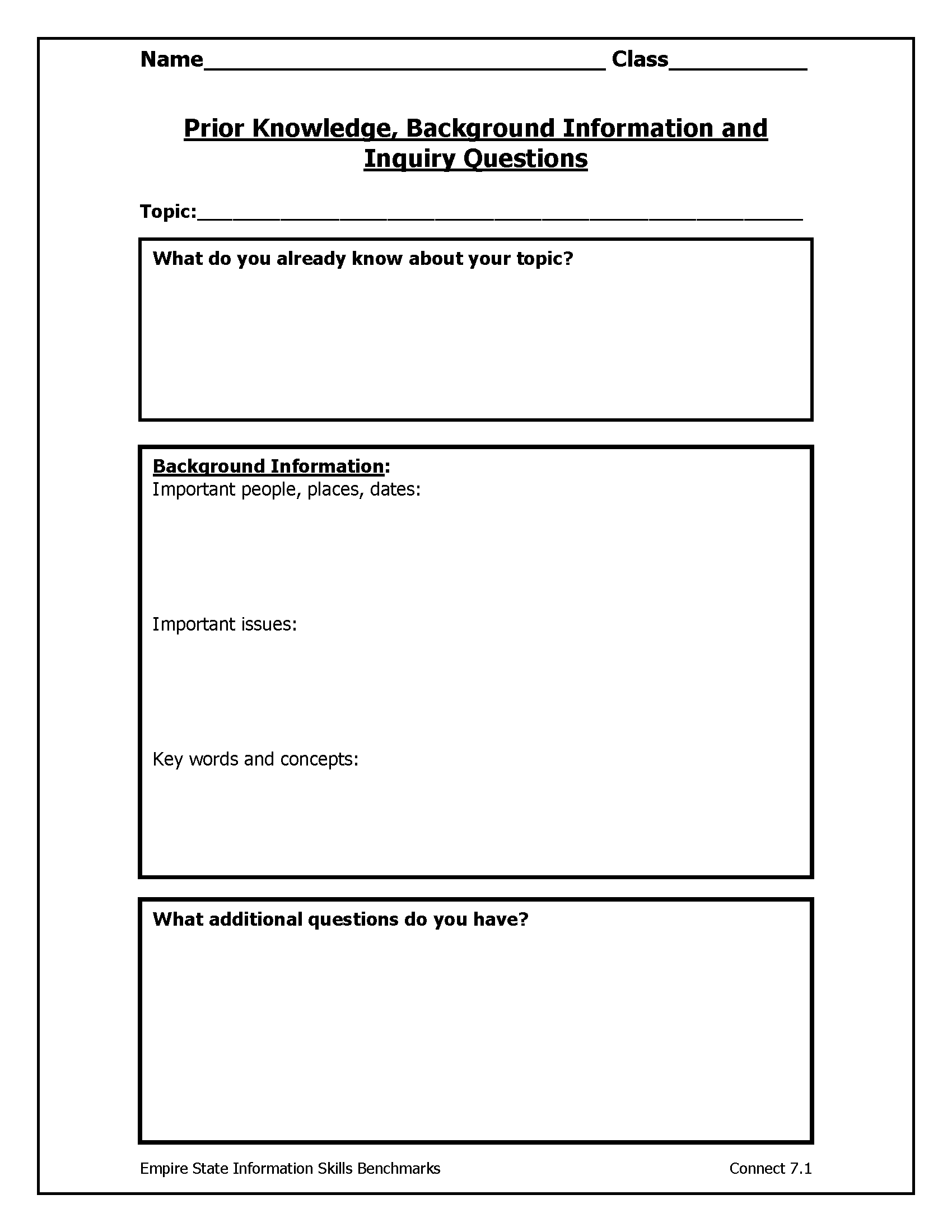

By the time students are in middle school, we can teach students to use their own prior knowledge and the background information they have gained to start asking inquiry questions (7.1).

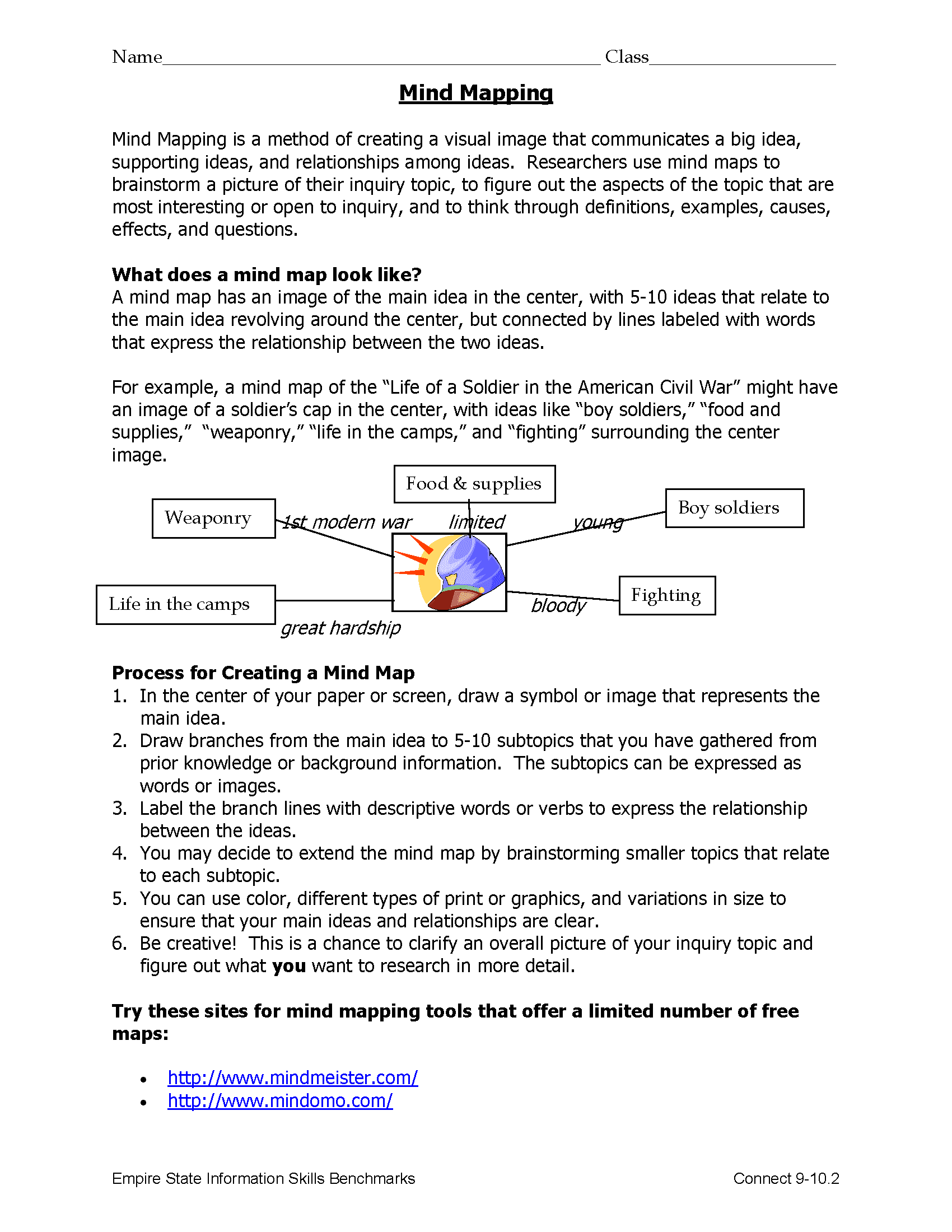

One of the important aspects of the Connect phase is for students to gain an overview picture of the whole idea, so that they can keep that context in mind when they select their focused topic for research. Librarians can develop a mind map with the whole class, with students contributing the ideas they have gained through their own reading or prior experience and the class deciding how the ideas fit together into a larger picture. Older adolescents can be taught to perform the complex reading skill of concept mapping independently (9-10.2).

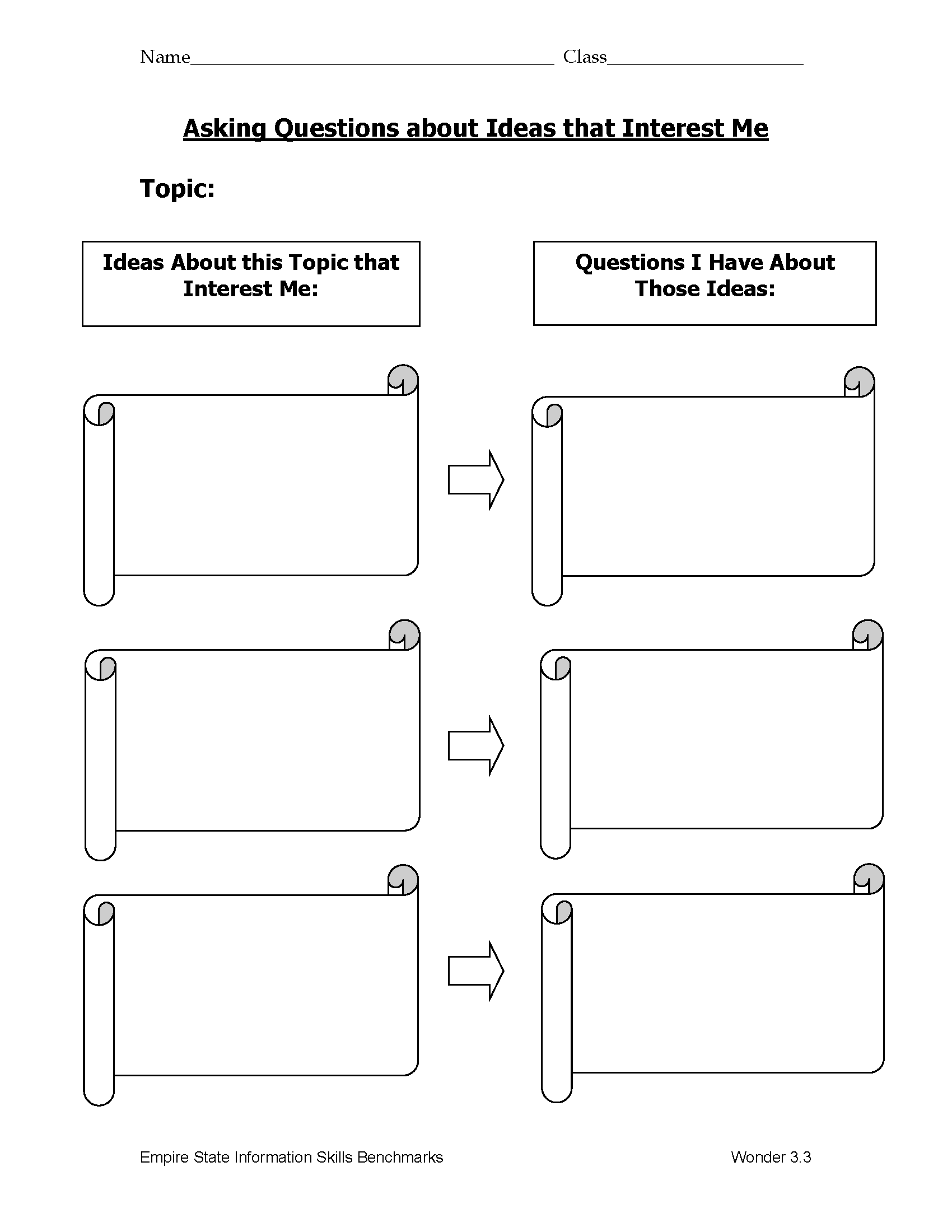

Wonder. Two of the deep reading strategies that enable students to develop Wonder questions that they are motivated to pursue are 1) to make sure that their questions emerge from a personal area of interest (3.3)

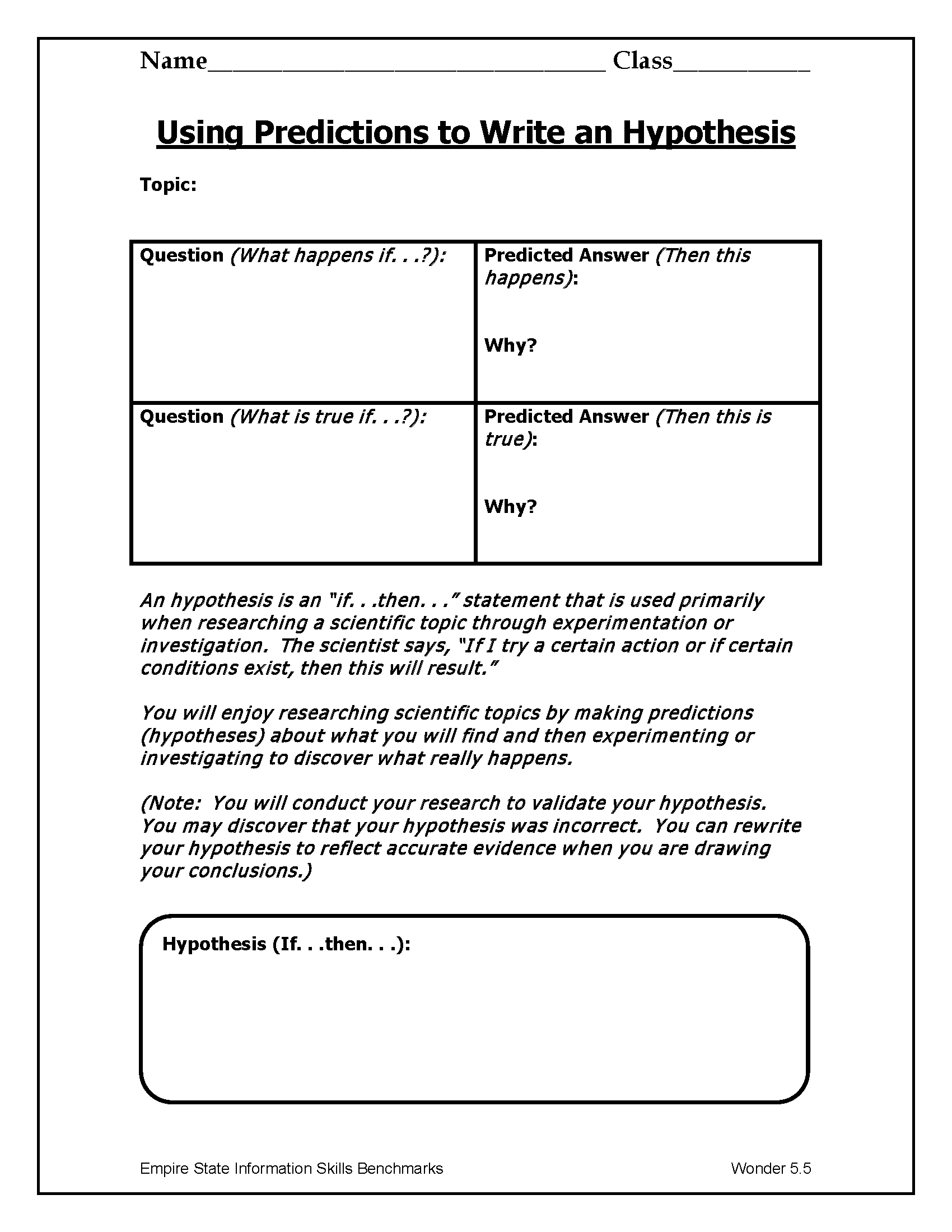

and 2) to guide them in predicting the answers they might find (and even to form an hypothesis based on their predictions) (5.5).

Reading experts have shared that, when students are personally invested and looking for answers to their questions as they read, they are more likely to read for meaning beyond simple comprehension of the text.

Investigate. Reading plays a prominent role during Investigate in any inquiry experience. The challenge for librarians is to teach students to interact with the text (in any format), to draw meaning that goes deeper than simply copying information, and to question, evaluate, and challenge the evidence they discover. The number of deep reading skills and strategies to be used during Investigate is quite large, but I have selected four skills that may not be as familiar to many librarians.

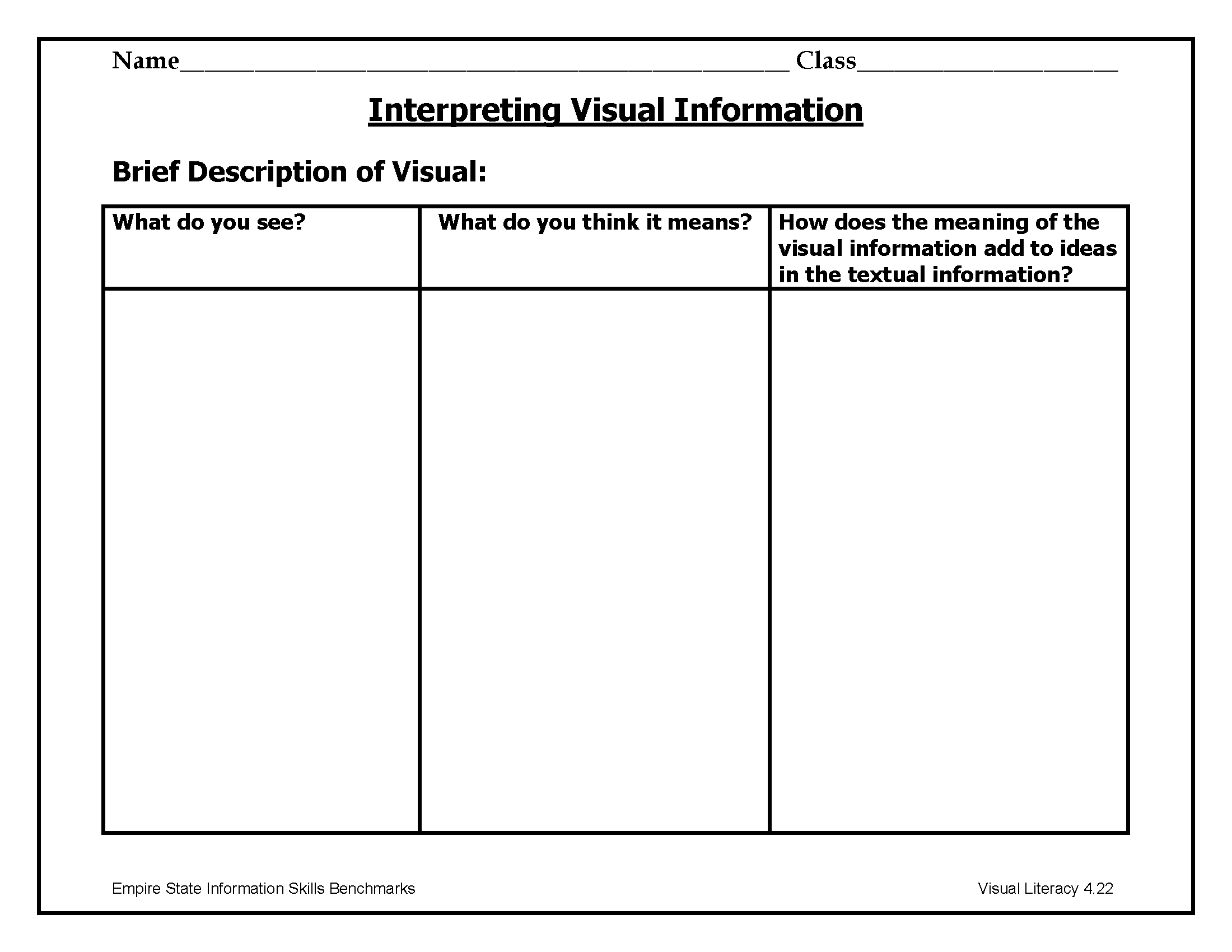

Much valuable information and alternative perspectives are offered through visualizations, including graphics, photos, art, political cartoons, and all forms of media. Students do not necessarily respond thoughtfully to visuals. Teaching that skill can start in early elementary (by drawing meaning from story book illustrations, for example) and can build in sophistication over the grades. The following graphic organizer could be to teach elementary students to interpret visual information (4.22).

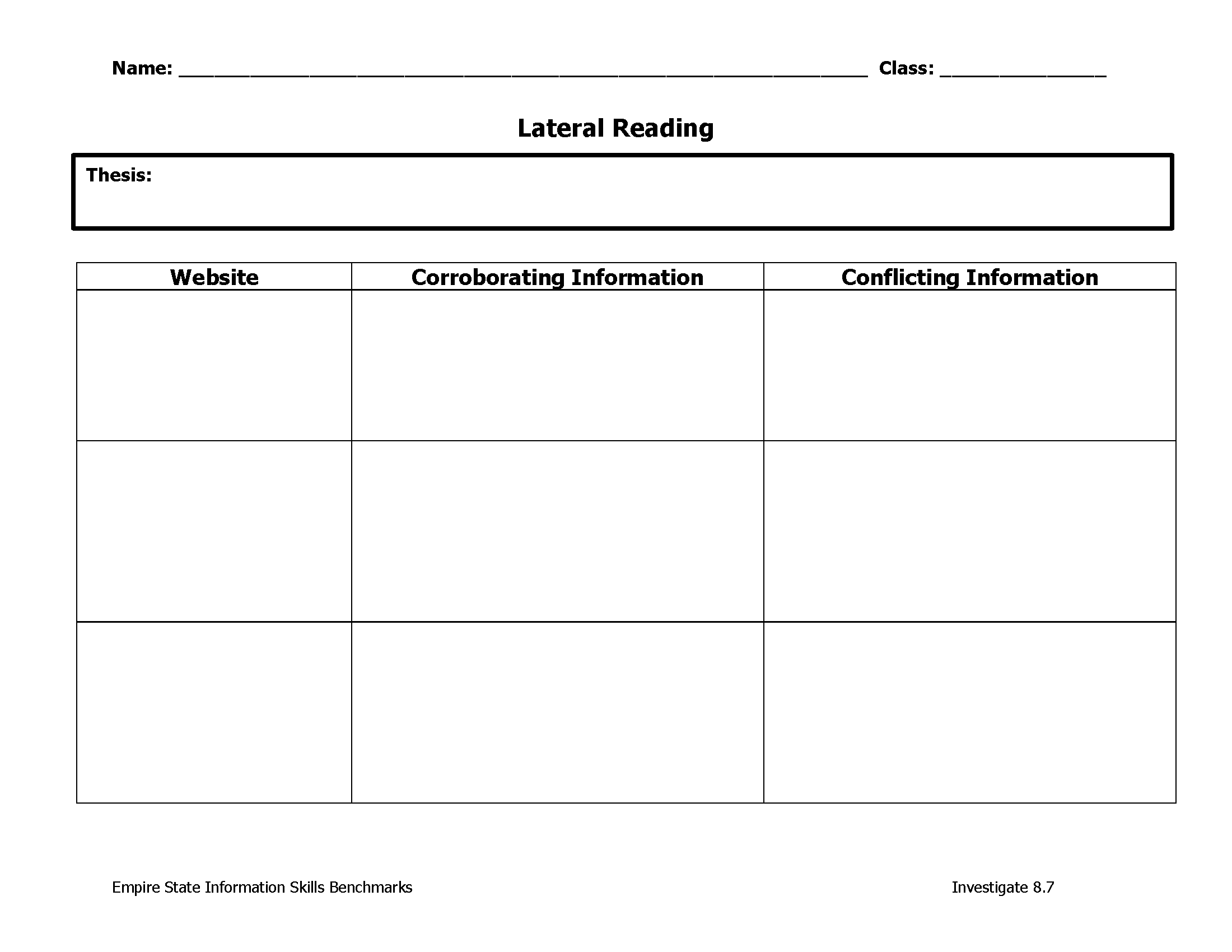

By the time students are in middle school, they should be expected to check their own inquiry process by making sure that they have been open to corroborating and conflicting information, rather than simply finding only information that confirmed their prior assumptions or their favored point of view. Teaching the strategies of lateral reading will strengthen and deepen their investigations (8.7).

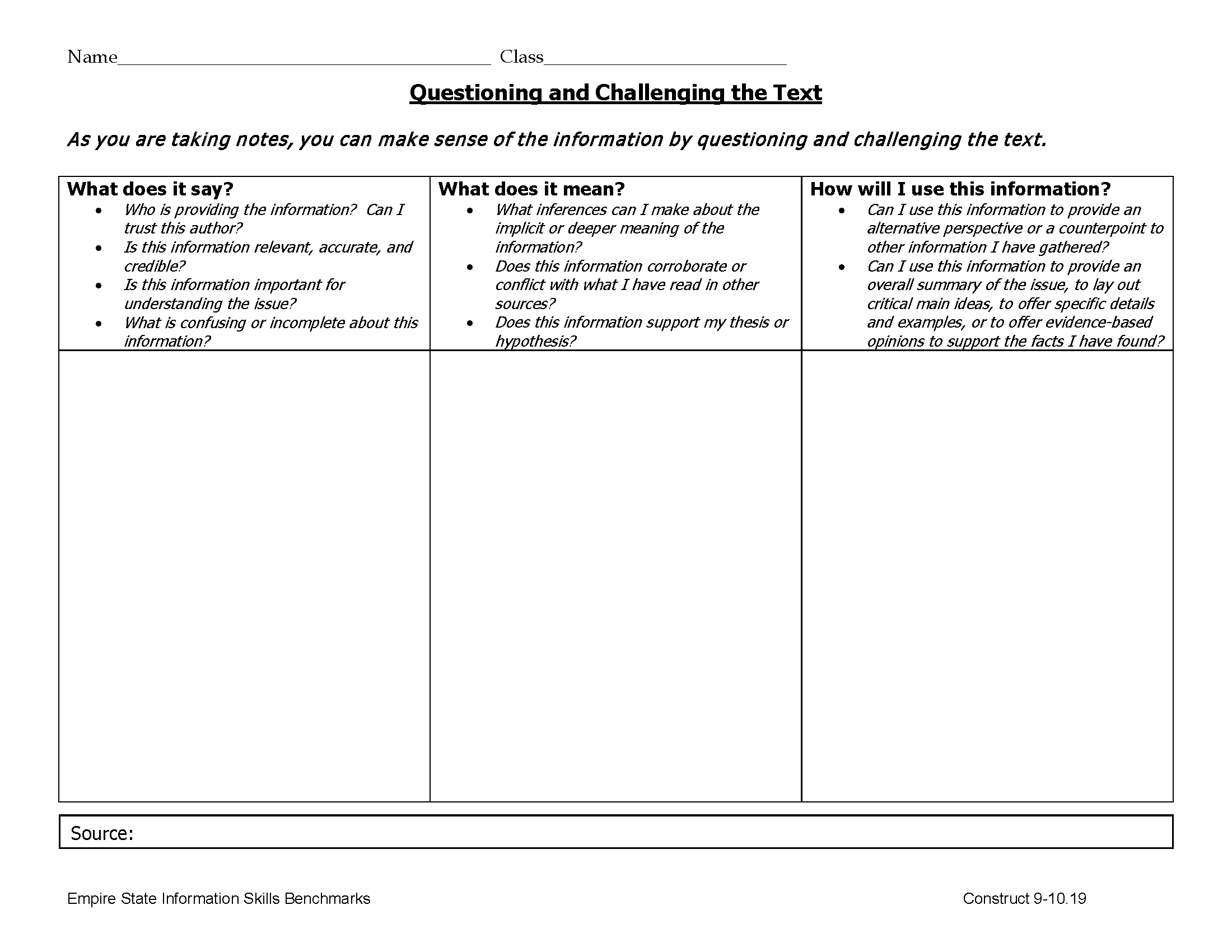

An important deep reading skill, to question and challenge the text, is honestly one of the most difficult to make a permanent habit of mind, for adults as well as young people. Often the time pressures of assignment due dates will lead to cursory reading and quick fact accumulation. Expecting students to take notes in a graphic-organizer format that is designed to generate reflection and questioning is an effective way to build deep reading and thoughtfulness into investigations. The graphic organizer below is one example that librarians might use (9-10.19).

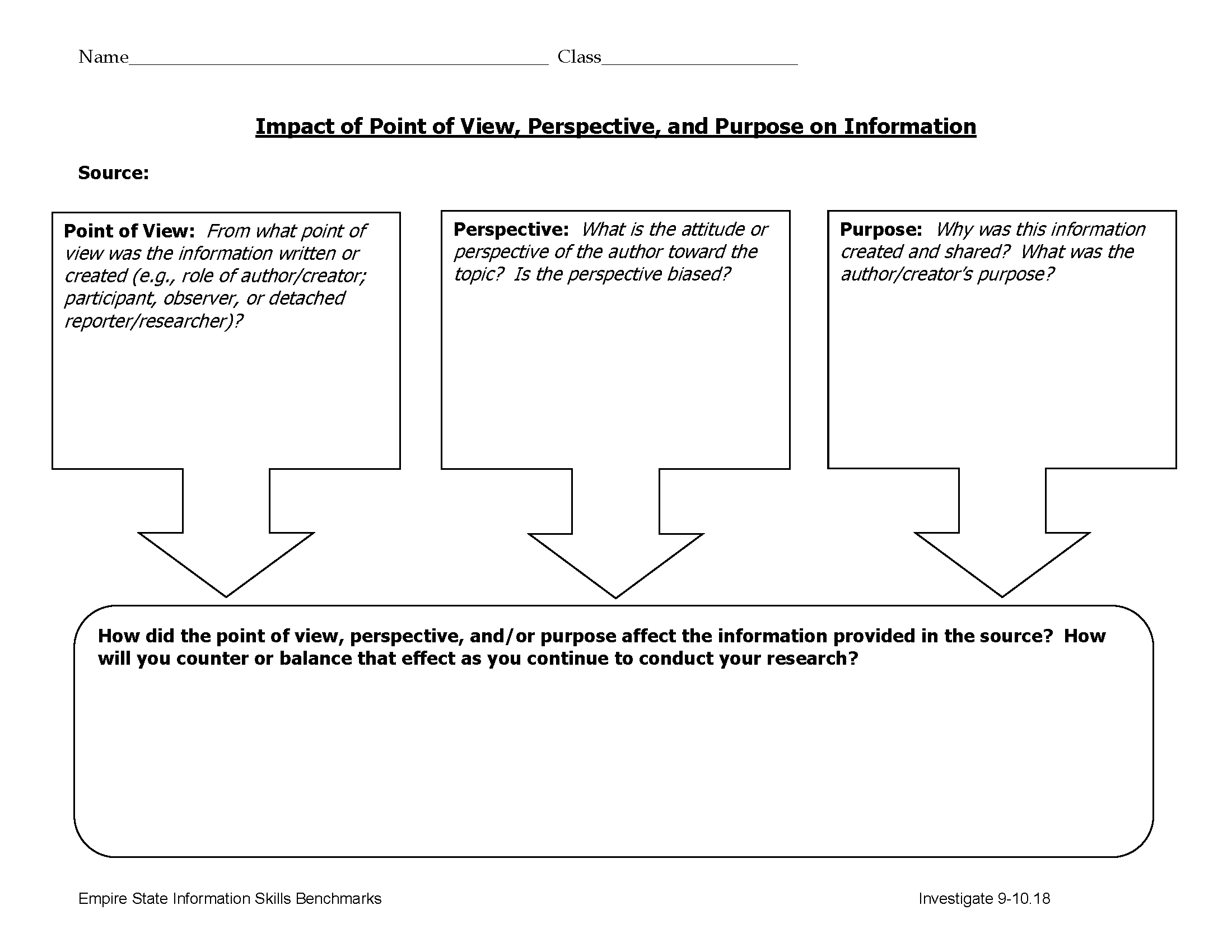

From the earliest moments in school, young people need to start identifying point of view in text that they read (or have read to them). Elementary students might start by looking at the point of view of characters in a story. These students must learn to transfer that skill to nonfiction texts during their inquiry investigations. By the time that students are in secondary school, they can be taught to assess the impact of point of view, perspective, and purpose on the information itself (9-10.18).

Construct. Although students may not be reading any new texts during the Construct phase when they are developing their own opinions and conclusions, they are re-reading their notes and perhaps sections of the sources they found most critical to their investigations. Reflective reading at this stage involves synthesizing the evidence they have discovered with the thoughts, opinions, feelings, and meanings that they have formed in response to the evidence.

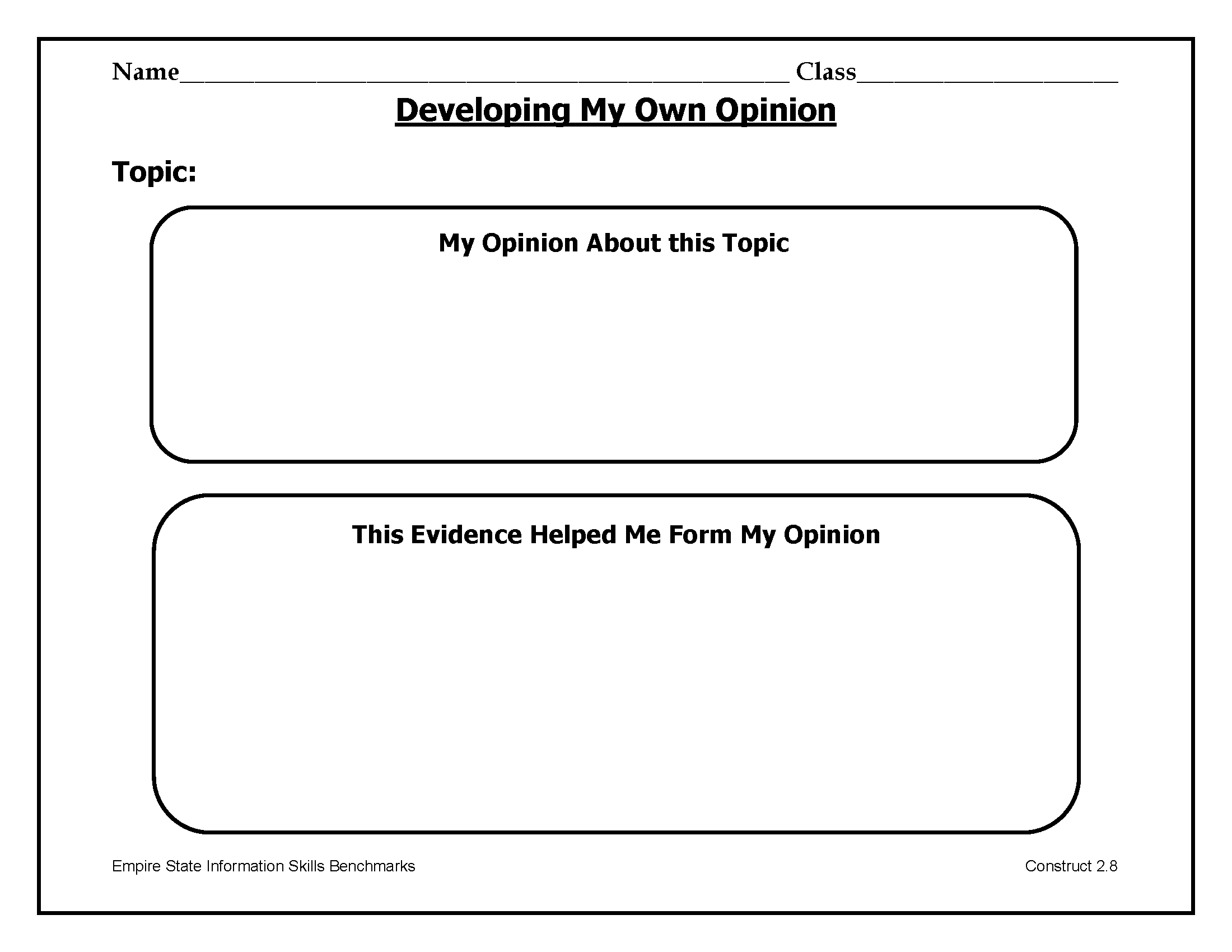

When I first started focusing on inquiry, both as a stance and as a process for learning, I remember simply telling my students to draw their own conclusions after they had found the information they needed. When I saw my students struggling, I realized that the deep reading and inquiry skills of Construct must be taught explicitly. Students may be able to form opinions naturally, but those are not opinions based on careful assessment of the evidence. I had to teach students how to construct their own ideas and understandings based on their investigations and their careful analysis.

Young students can be taught to form their own opinions in early elementary. The essential piece is that they must tie their opinions to the evidence they have heard or discovered (2.8).

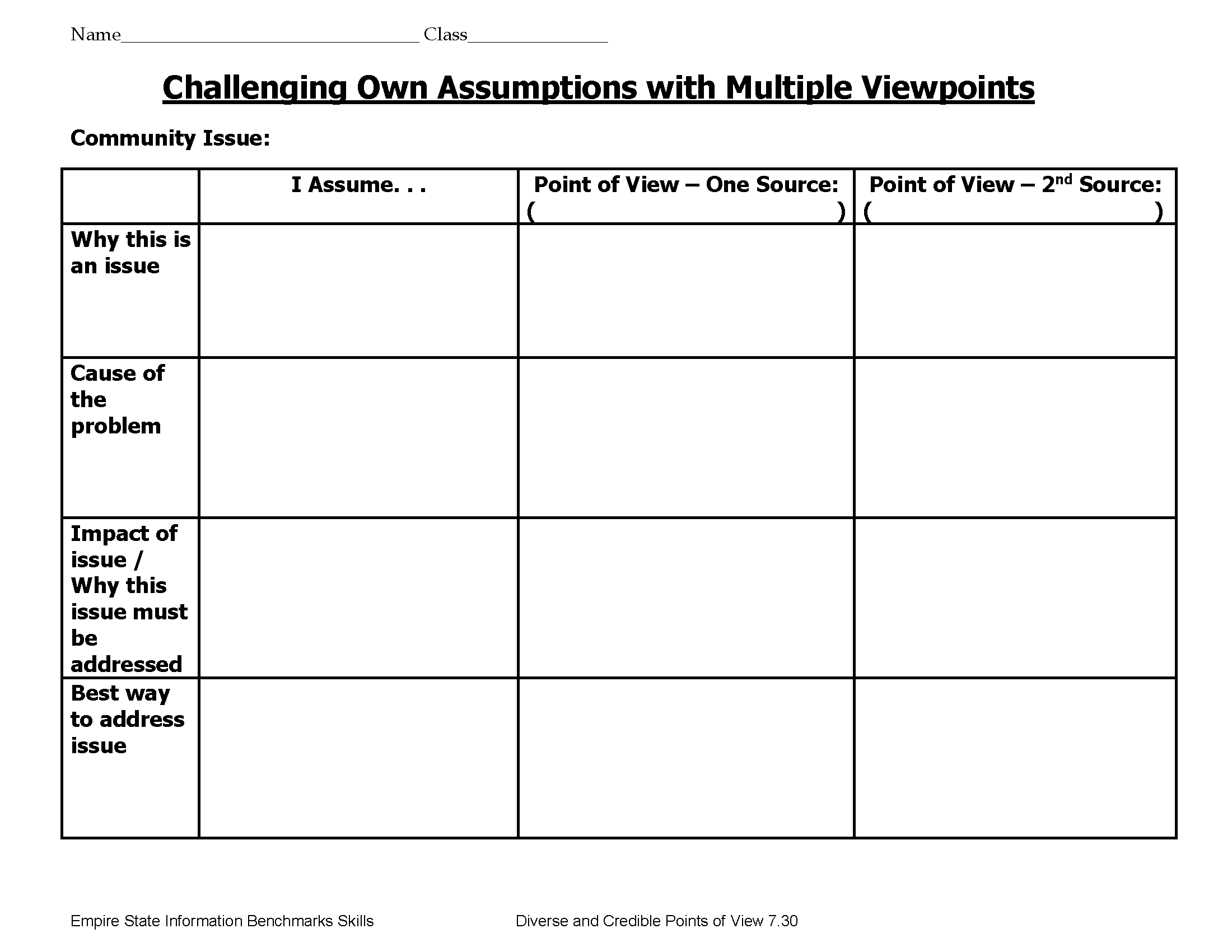

By the time students are in middle school, they should be expected to identify their own assumptions and challenge them by considering multiple viewpoints (7.30). Direct instruction on how to identify the viewpoint or perspective of a text, plus graphic organizers to guide them through the analysis process, will enable students to construct their own understandings based on evidence.

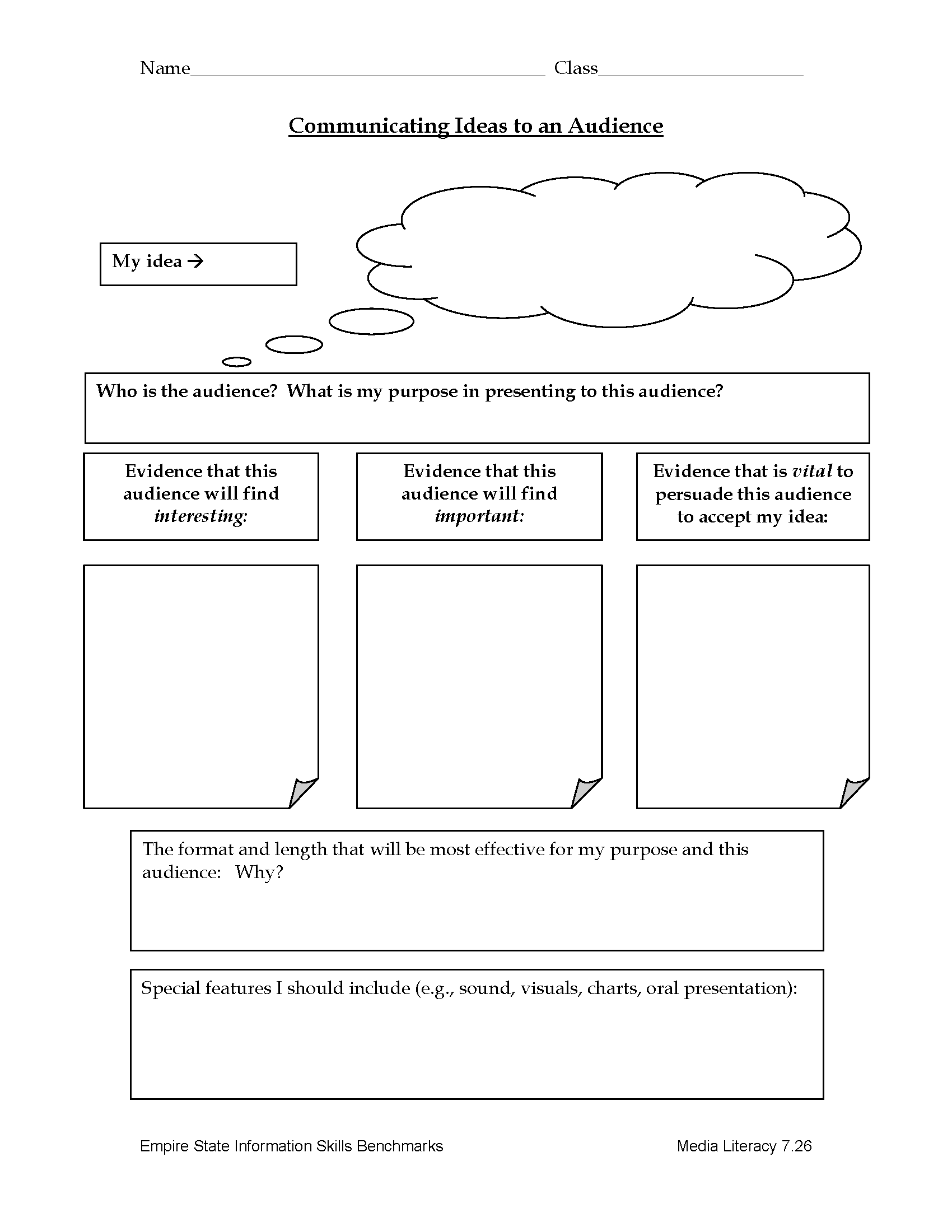

Express. A broad interpretation of deep reading skills at the Express phase includes teaching students to use language and other communication tools to create and share expressions of their new understandings. As leaders of inquiry for the whole school, librarians are in an excellent position to assume responsibility for teaching students the creation and presentation skills that will be relevant whenever they have the opportunity to share their learning. One communication skill that is rarely taught is “reading” an audience and tailoring a presentation to appeal to that audience (7.26).

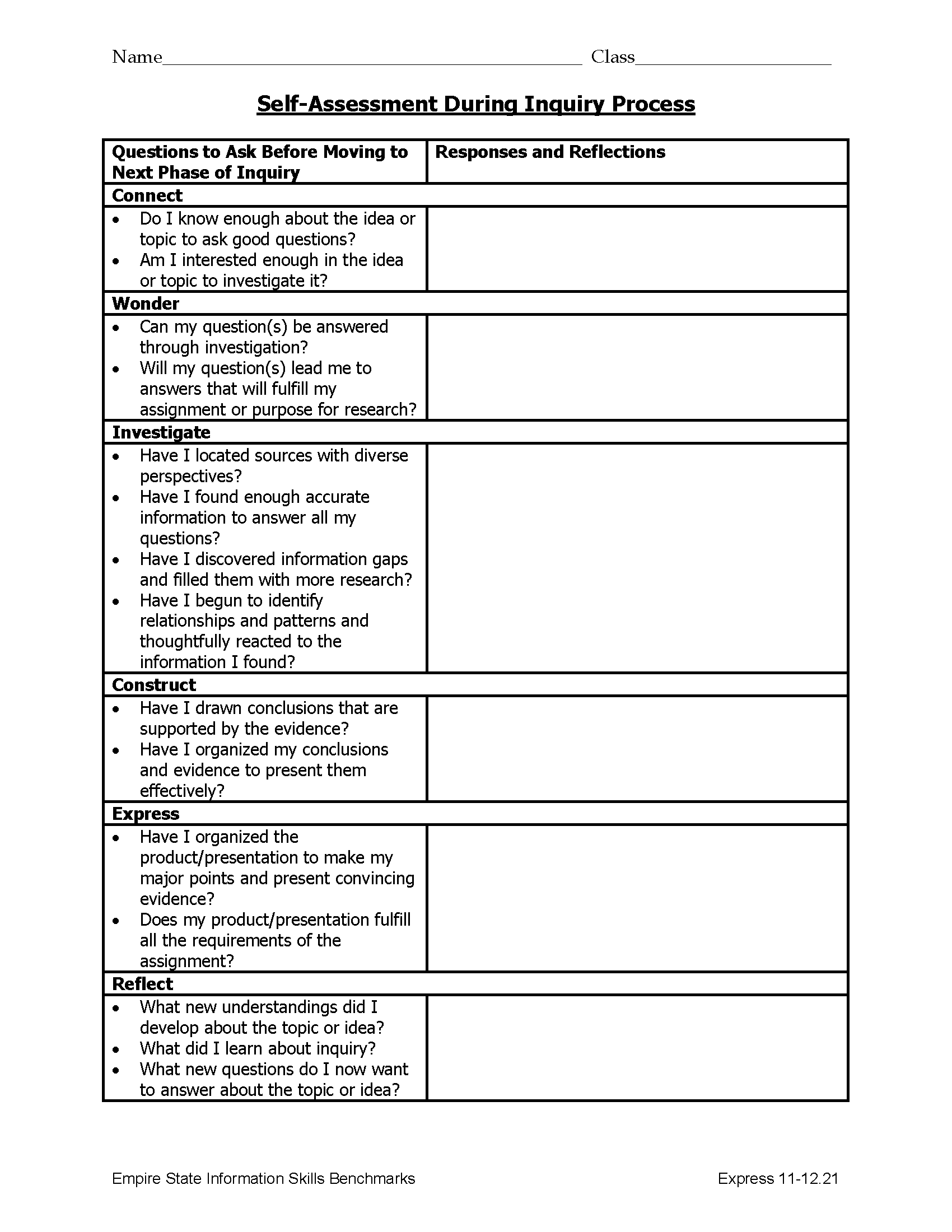

Reflect. Although reflection is built in to every phase of the inquiry process, the value in reflecting on the entire process and product at the conclusion of the inquiry experience is that it enables the learner to move from a look at one experience of inquiry to a broader perspective on inquiry as a process and a stance on learning. The concluding reflection allows the learner to self-assess and to be in charge of setting personal goals for improvement. The first template below offers questions for the learner to ask himself throughout the process of inquiry (11-12.21).

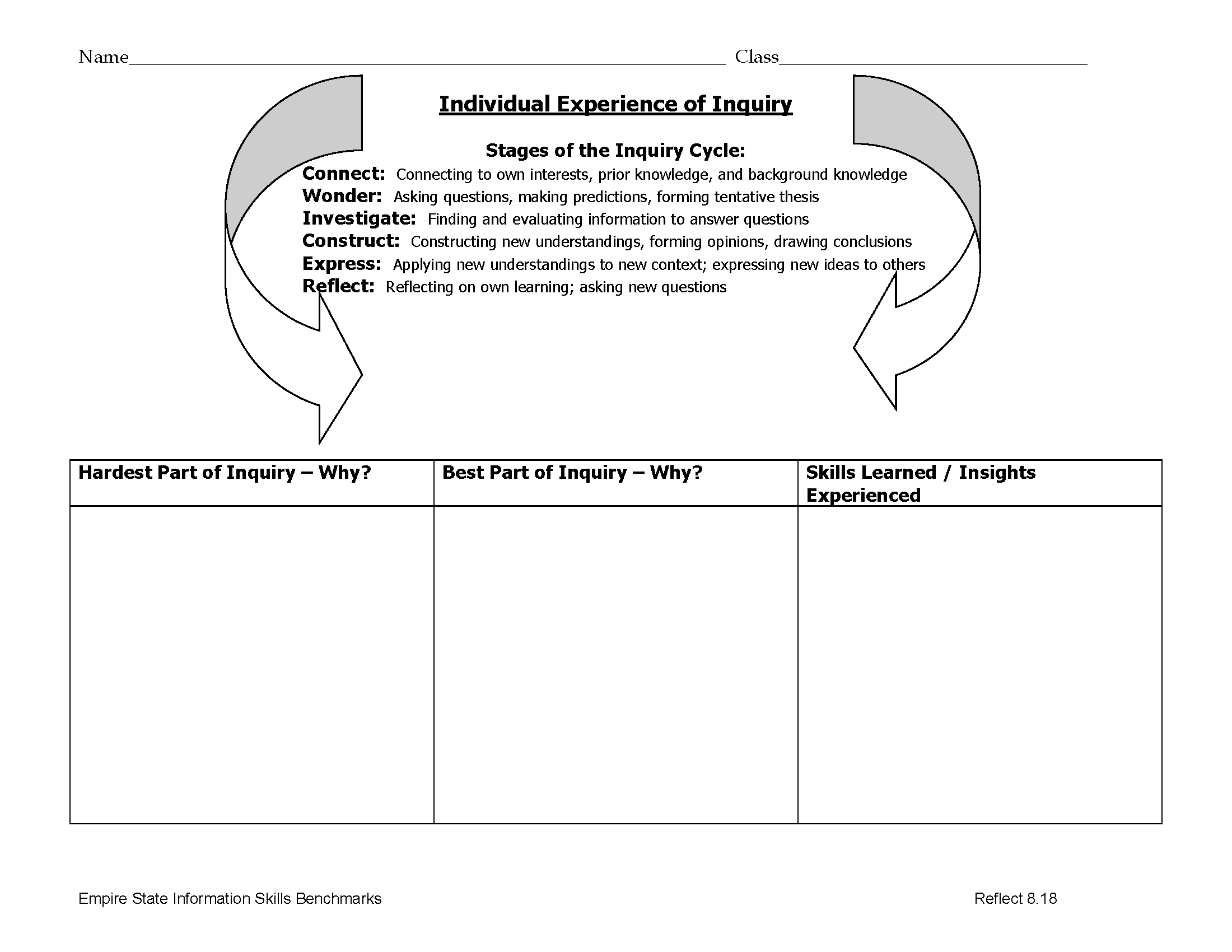

Students at every grade level can be asked to think about their individual experience of inquiry. The graphic organizer below can be adapted for any grade level (8.18).

Half of the fun of using graphic organizers in order to guide students during their independent practice is designing organizers that enable students to be transparent in their thinking while they are performing a skill. Librarians can use these formative assessments to discover when students are struggling and perhaps even where their confusions lie. Students have a sense of completion and success when they have been able to successfully follow the thinking process inherent in the deep reading and inquiry skills we are teaching.