Reply To: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment › Reply To: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment

Ahead of the Q&A on Sunday, and opportunity to reflect on the discussion so far.

It appears to me that for many school librarians there is a paradigm shift that needs to precede the paradigm shift that Barbara refers to in her chapter, which is to recognize that the school library has a clearly defined pedagogical programme, and that the impact, and therefore value, of the school library is directly linked to the quality of this programme. This pedagogical programme is outlined in Chapter 5 of the IFLA School Library Guidelines, which draws on over 60 years of international research into the effectiveness of school libraries. For reference, the 5 core instructional activities of the professional school librarian are: (1) Literacy and reading promotion; (2) Media and information literacy instruction, which may be within an (3) Inquiry-based learning model; (4) Technology integration; (5) Professional development for teachers.

As a consequence of the school library’s pedagogical programme and the school librarian’s core instructional activities, the school librarian is a teacher, regardless of whether they recognize it or not, which is part of this first paradigm shift.

The question is, a teacher of what?

This question gives rise to the second paradigm shift.

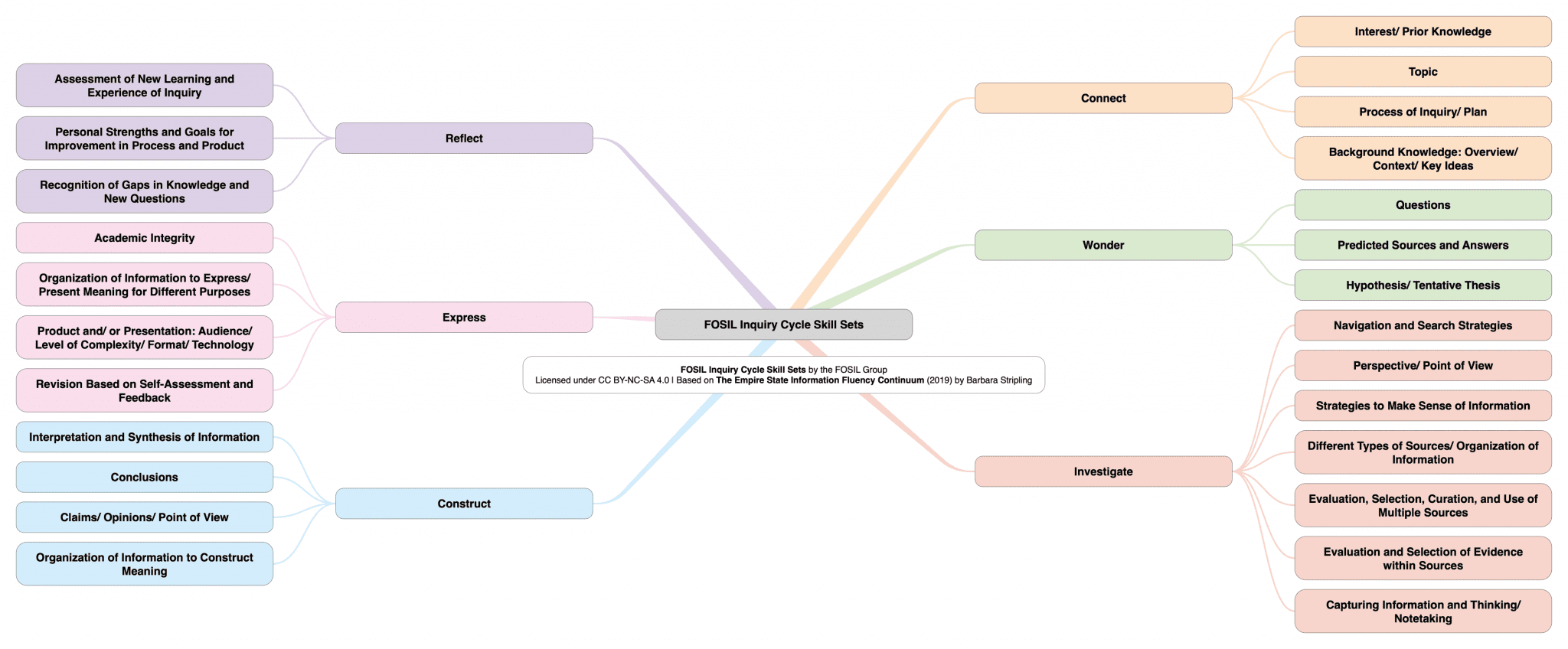

In E&L Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry, Barbara makes the point that John “Dewey’s recognition of the need for both content and skills provided solid justification for the role of a school librarian as a teacher of sense-making skills”. This contours the second paradigm shift for me, which is a shift from a narrow concern with sources of information – mainly the information search, evaluation and retrieval aspects of Investigate, and the academic integrity aspect of Express (see Figure 1 below) – to a broad concern with the full process of learning from information in the context of subject area teaching. This process of learning – building knowledge and understanding/ making sense – from information is the school librarian’s subject specialism, and the basis for collaboration with classroom teachers/ colleagues.

This takes time, and is more or less difficult depending on our particular circumstances, but take courage – I have been wrestling with this on some level since becoming a school librarian in 2003, and Barbara for far longer, yet here we all are. It is worth reiterating Barbara’s point above that she has learned the most about the skills she needs to teach students by engaging in inquiry as a learner herself and reflecting on the process, and my point above that the tag line for FOSIL, reflecting my insight into this process, is Learning by finding out for yourself (not by yourself, which suggests minimal or no guidance and/ or interventions).

To understand why this paradigm shift matters, recall our expanded definition of inquiry, which is “a stance of being open to wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community“. Evidence of our collective failure to effectively educate to this end is overwhelming, hence the urgent necessity for this second paradigm shift, which, as Barbara points out in her chapter, is still underway. Furthermore, a paradigm shift is always traumatic, but the second one will be doubly so for those colleagues who have not yet recognized the signs of the first one.

While our primary concern is with inquiry learning in the context of subject area teaching, the IB document Ideal libraries: A guide for schools that I referred to above reminds us that “libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin” (p. 9). This means that the nature of the library as a learning space, which is different to the classroom as a learning space, will provide opportunities for both formal and informal interventions in student inquiry that the classroom does not – which is why, “ideally, the librarian is trained in many ways of creating conditions for inquiry within and beyond the classroom” (p. 9) – but always in our role as teachers of sense-making skills.

Then, we get to what I think is a third paradigm shift, which is the shift from a predominantly print to a predominantly digital environment. Marshall McLuhan’s insight that the medium is the message – or massage, in that the medium works us over completely (1996, p. 26) – is helpful, because while our concern remains understanding what is said, the digital medium through which it is said problematizes understanding in a paradigmatically different way. This means that we are needing to simultaneously deal with two problems: the age-old problem of building knowledge and understanding from information, mainly though reading (see Reading for Inquiry Learning, particularly from this post onward); the new problem of the digital medium, which McLuhan, quoting A. N. Whitehead (pp. 6-7), warns is a major advance in civilization, and that “the major advances in civilization are processes which all but wreck the societies in which they occur” (consider, for example the 25 March 2021 US congressional hearing into the role of social media in promoting extremism and misinformation, with specific reference to the 6 January 2021 insurrection at the Capitol – Google, Facebook Twitter grilled in US on fake news).

This – and for other excellent reasons raised in this discussion, particularly related to the physiology of reading – means that at times we will need to critically embrace the digital medium, while at other times we will need to actively resist it.

This also overlaps with the discussion about CRAAP (or other) testing.

Inquiry, as we have said, is a stance, or attitude, of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic learning process. This dynamic inquiry learning process proceeds through distinct but interrelated stages, each of which is enabled by concrete skills that need to be developed systematically and progressively, and between the library and the classroom, over the course of a student’s time at school.

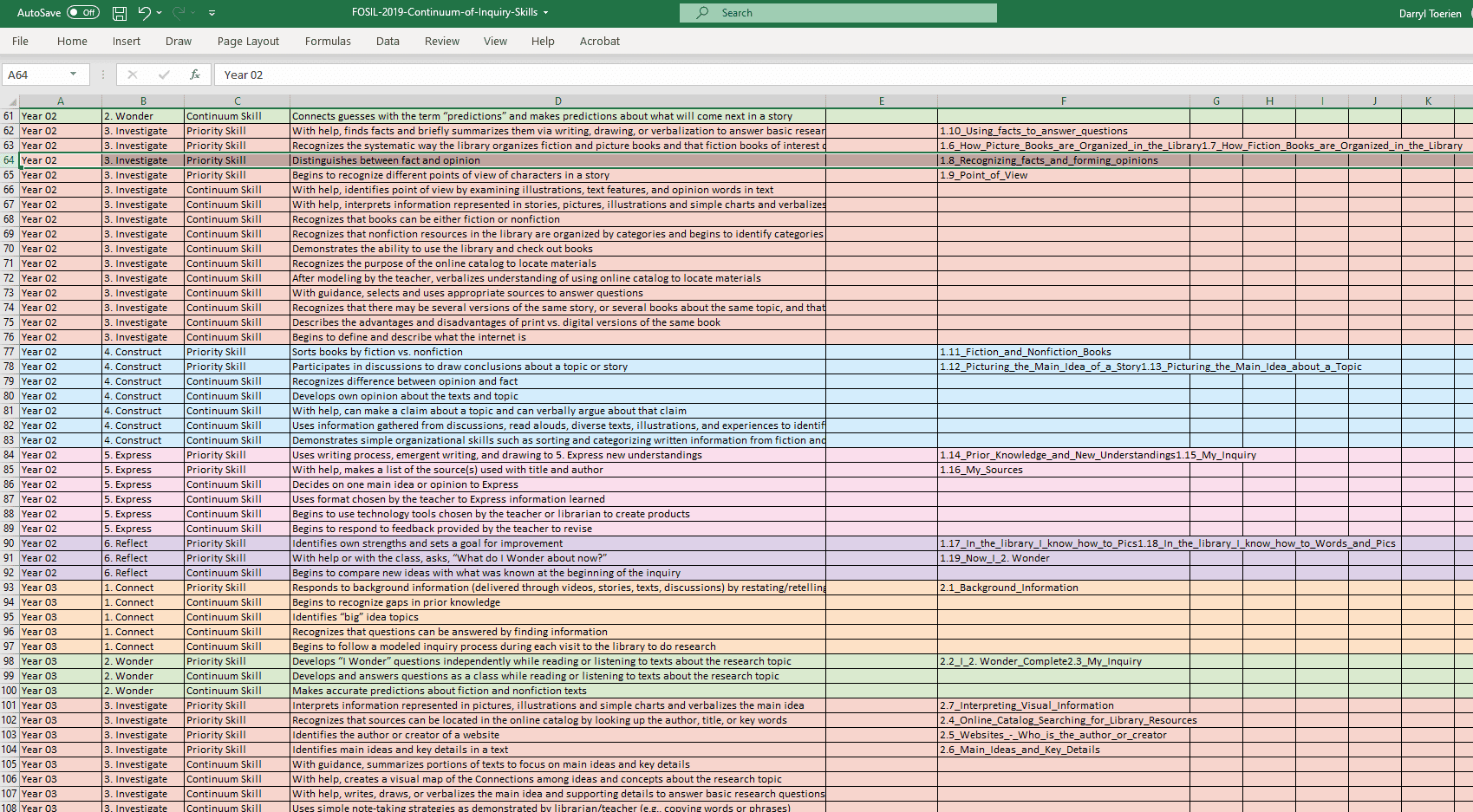

(It is worth reminding ourselves that FOSIL, based as it is on the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, is all of these things – a robust framework/ model of the inquiry process, a highly coherent PK-12 (Reception-Year 13) framework/ continuum of concrete inquiry learning skills, and a growing collection of specialized graphic organizers that can be adopted/ adapted for instructional and/ or formative assessment purposes – and more – the FOSIL Group is a growing international community of inquiry that has grown up around FOSIL, but is not limited to FOSIL, and one that benefits from active collaboration with Barbara.)

Even at the Skill Set level, or what the ESIFC terms Indicators, a concern with “bullshit and the art of crap-detection” (Postman, 1967) is evident, particularly in the Investigate and Connect stages (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: FOSIL Cycle Skill Sets

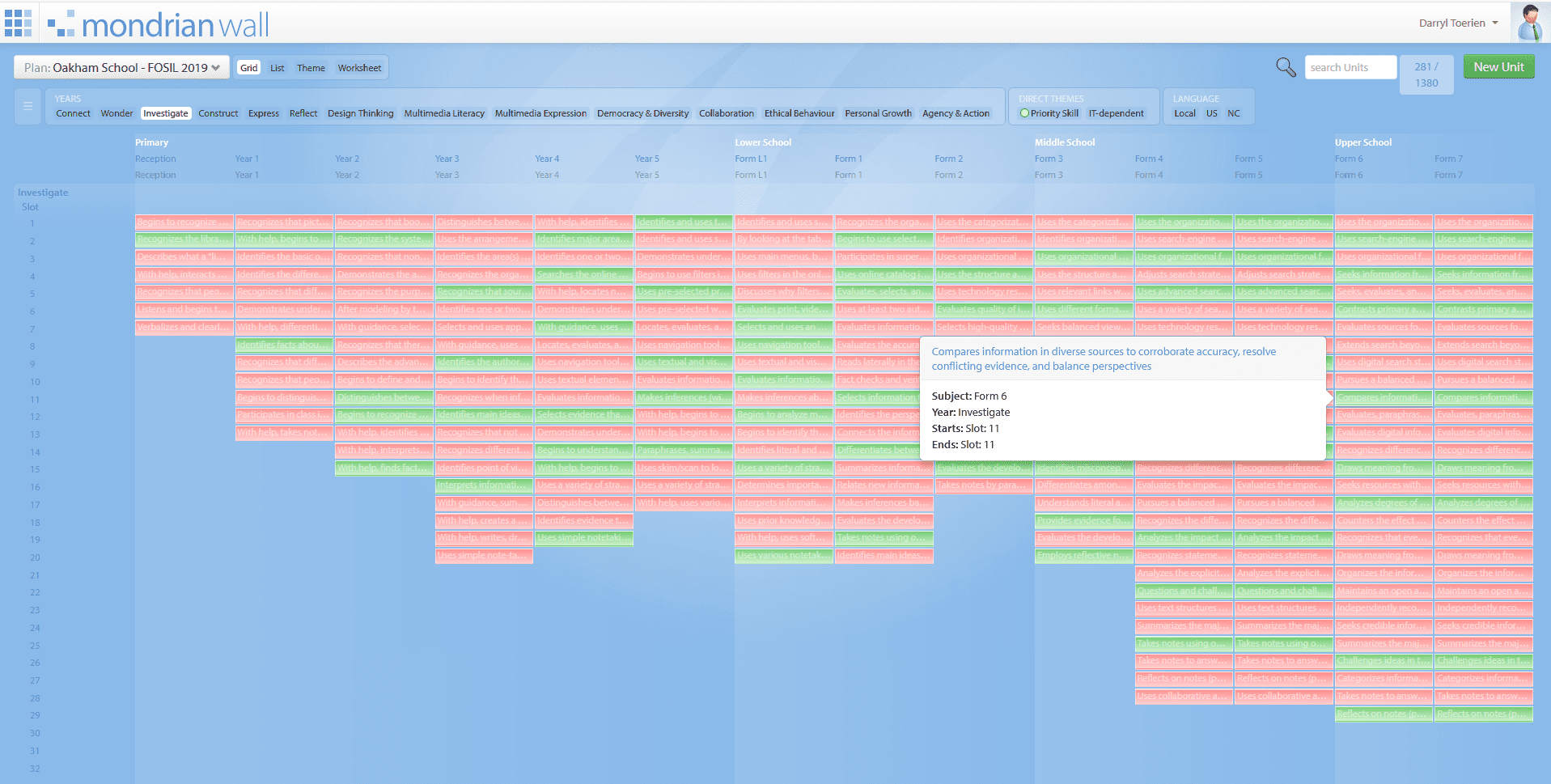

At the Skill level, this stance, or attitude, towards “bullshit” gives rise to a developmental continuum of concrete skills that enable increasingly sophisticated “crap-detection” (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 below, for example).

At the Skill level, this stance, or attitude, towards “bullshit” gives rise to a developmental continuum of concrete skills that enable increasingly sophisticated “crap-detection” (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 below, for example).

Figure 2: Priority Skills (Green) and Continuum Skills (Red) in the Investigate Stage

Figure 3: Snapshot of Priority and Continuum Skills for All Years and Stages

It is important to point out that, like with the CRAAP test, this is not a crushing list of skills to teach, but rather a developmental description of the skill sets that children need if they are to be be effectively equipped for the lifelong task of learning for themselves – hence the identification of priority skills, and even those are up for thoughtful debate in our local contexts.

This is what I find is missing from most discussions about the inability of students to discern misinformation, disinformation and malinformation, especially from the perspective of university, which is the recognition that our system of schooling is perfectly designed to achieve the results that it is getting – without a systematic and progressive approach to developing the skills that enable the process of effectively learning from information within the context of content area teaching, we bear responsibility for their inability to do so outside of or beyond school. This, then, is much more than the failure of a tool, or even a failure in our approach to using that tool.

Thanks, Helen, for the encouragement and also looking forward to Sunday.

References

- IBO. (2018). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organisation.

- McLuhan, M., Fiore, Q., & Agel, J. (1996). The medium is the massage. London: Penguin Books.

- Postman, N. (1969, November 28). Bullshit and the Art of Crap-Detection. Retrieved from Escaping from Bullshit: http://ditext.com/wordpress/2018/10/08/neil-postman-bullshit-and-the-art-of-crap-detection/