Reply To: Year 6 (Grade 5) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College

Home › Forums › Inquiry and resource design › Year 6 (Grade 5) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College › Reply To: Year 6 (Grade 5) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College

Reflections on the Science lessons (Darryl has already linked to the Cool Water Experimental Journal in a previous post).

When I have done this experiment before (also as part of the CREST award, way back when I was a Science teacher), I have found it can become a bit chaotic with students being unsure what to do and finding it very challenging to plan genuinely fair and meaningful experiments. In the past, after a few lessons of playing around with the equipment, they will all have gathered some data, but for some groups it can be debatable how useful this data is. They will often have some idea of what fair testing means, but find it hard to achieve in practice. Particularly with time constraints. Indeed, with my Science technician hat on, I had to conduct quite a number of different trials with lots of different kit to come up with a procedure and set of apparatus that would produce reasonably different results with a range of different insulators over a fairly short time period (in this case, around a 16C temperature drop over about 10 minutes from a starting temperature of around 80C). The students would never have had the time to do this before starting their experiments.*

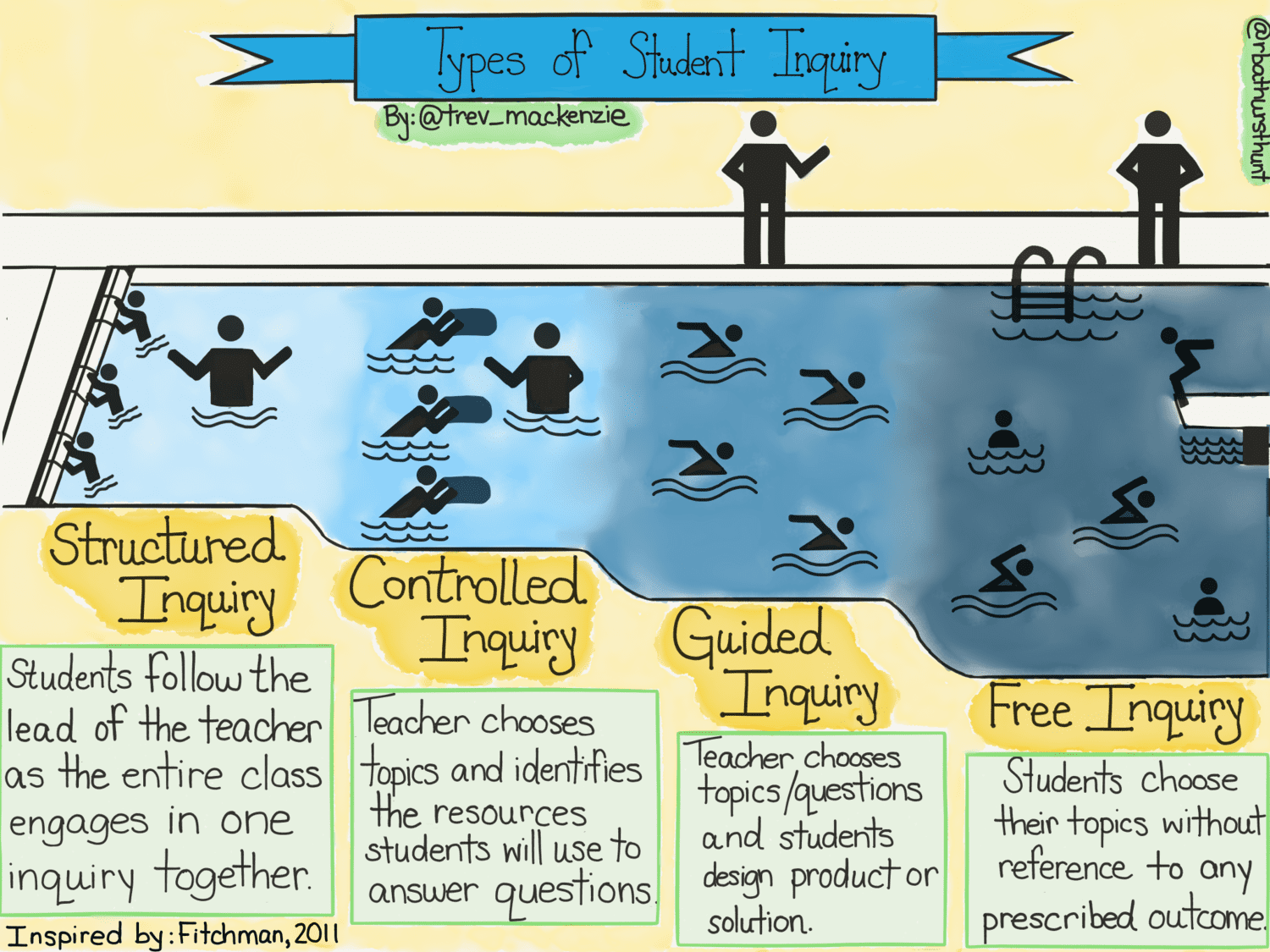

Like any form of inquiry, Scientific inquiry skills need to be purposefully taught and practised. If practical work is usually ‘recipe style’ and opportunities for genuine inquiry or even some level of decision making are rare (as is often the case), then you cannot just expect students to intuitively know how to do it. We decided to focus on the idea of fair testing, and stepped students through a controlled inquiry to determine which insulators were the most effective. The group talked together about how to make the experiments fair, and how to make sure that they were all doing them the same way so that they could pool their results at the end. Although the method was quite tightly controlled, the emphasis was on students understanding why it was important to conduct the experiment in this way.

In the back of my mind I have Daniel Callison’s book on ‘Controlled, guided, modelled and free’ inquiry and Trev MacKenzie and Rebecca Bathurst-Hunt’s sketch on types of student inquiry. Inquiries can be conducted at many different levels and we need to choose a level appropriate to the skills and experience of the particular students – with the aim that we start off heavily scaffolded and that scaffolding gently drops away with age and experience.

A key component of this part of the inquiry was time. Because I was teaching some of the heat transfer theory through the English lessons, and graphs would be plotted in Maths and ICT, this freed up the Science teacher to really focus on the practical. He commented afterwards how valuable it was to spend four lessons (around 1 hour each) on the same experiment because this is not something they would normally be able to do, and how much the students’ experimental technique and understanding improved as they had the opportunity to learn from their mistakes. The students were excited by the experiments (and the tie-in with the water bottle covers that they were going to make) and enjoyed being able to return to the same apparatus over a number of weeks and improve their technique.

The downside of this slightly more controlled approach is that it does reduce student autonomy somewhat, so in order to meet the CREST criteria on decision-making and planning I felt we needed to add another strand to the inquiry – over the next few weeks the class will be planning a campaign to reduce the use of single-use plastics in the school (linked to making their reusable water bottles more attractive to use by making the covers). They will have the opportunity to drive and plan this themselves (with some guidance, of course!), which will help them to meet these criteria for the CREST award.

[*If you want to know, a 100ml plastic measuring cylinder filled with 100ml of freshly boiled water and a thermometer clamped and pushed through (at about the 20C mark) a disposable cup lid just touching the top of the cylinder works really well. If you also prewarm the apparatus you can get perfectly reproducible results – as evidenced by that fact that several groups in one class managed to get identical results. They were so excited to feel like real scientists! You can then precut equally sized rectangles of different materials to wrap around the whole height of the cylinder and secure at top and bottom with rubber bands. In my trials I found that the small plastic cups, and even glass beakers, which are commonly used for this experiment instead of the cylinders were too affected by heat loss through their bottoms and didn’t have enough surface area covered by the insulating material to be particularly discriminating between different materials.]