Session 1a: Elizabeth Hutchinson & Darryl Toerien (Welcome)

Home › Forums › FOSIL Presentations › 2025 FOSIL Symposium › Session 1a: Elizabeth Hutchinson & Darryl Toerien (Welcome)

- This topic has 1 reply, 2 voices, and was last updated 1 year ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

11th February 2025 at 7:44 am #85503

Post here for comments and questions relating to the session:

08:45 – 09:00 | Welcome | Elizabeth Hutchinson, School Library Specialist

Link to YouTube recording.

11th February 2025 at 8:05 am #85511Because of the structure of the day and time constraints, I did not share my full introductory remarks, which are, in fact, a welcome. I have, therefore, included them here in full, both for context and the record.

—

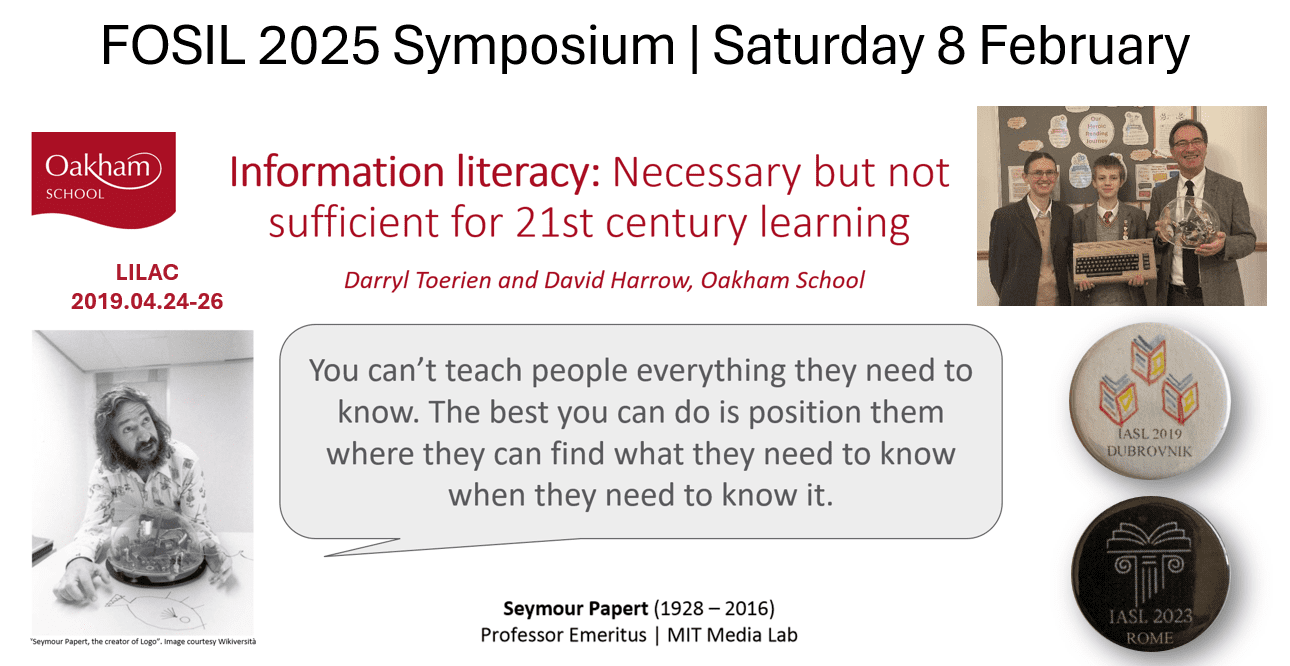

I have longed for this day since announcing the FOSIL Group in a presentation at LILAC 2019 and am overjoyed to be in such fine company – more than 200 colleagues from more 25 countries.

Apart from its historical significance, the title slide from this presentation encapsulates much, if not all, of what draws us together today. The picture of Jenny, Reuben and me – along with a genuine Edinburgh Turtle and Commodore 64 – is from this morning, because we have had the privilege of meeting many of you, and some of you have asked after Reuben, who is doing very well thank you, and who has grown quite tall for someone who still has 6 months to go until his 12th birthday.

So, while I could spend all of my time today drawing this significance out, I will highlight only the following:

- I was blessed to meet Seymour Papert, who profoundly influenced my understanding of how we learn, and in learning, the use of technology as tools to think with.

- I was blessed to discover a genuine Edinburgh Turtle, which was developed by the University of Edinburgh’s Artificial Intelligence Department to work with Seymour Papert’s Logo programming language, which is what the LEGO Mindstorms robotics platform was based on.

- I was blessed to grow up during the microcomputer revolution of the 1980s, which placed an extraordinarily powerful tool to think with in the hands of school-age children, hence my modest collection of 8- and 16-bit microcomputers. My most formative years at school were spent, therefore, in Computer User Group meetings, which embodied the hacker spirit at MIT, out of which the microcomputer revolution grew, and where Seymour Papert co-founded the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory with Marvin Minsky.

The culture of the various Computer User Groups was radically inclusive – all that was required to join one was an interest in computers, and joining one wasn’t even necessary to attend their meetings, which were free and open, and often held in school halls, where if you needed to learn something you found someone to teach you, and if you knew more than someone else you taught them. They were also, therefore, radically diverse, to the extent that it was possible in Apartheid South Africa, and contributed in some part to undermining that wicked regime.

This culture profoundly influenced me, and the hacker spirit – figuring things out for yourself with help from wherever you could find it, and sharing what you’ve learnt with whoever was interested, which is the spirit of inquiry – animated me, and this is how I approached the development of FOSIL and the FOSIL Group. More on this later.

Conventional wisdom has it that you shouldn’t start a communication with an apology – so, sorry for starting with an apology.

If what I say sounds scripted, that is because it is. The reason for this is that your time is precious, and the best way for me to honour your generous gift of time is for me to be as purposeful and deliberate as possible with what I say. Having said that, countless hours over many sleepless nights was not quite enough to finish things as I would have liked, so you will find me rough but ready in some places.

Thank you, then, for being here today, especially those in other time zones, whose sacrifice of time is greater than most, which means that it is accurate to say good morning, good afternoon and good evening to you. Thank you especially to those dear colleagues who are sharing with us today, and without whom we would not be here, and to Elizabeth for technically the same reason. We, and certainly I, would not be here without Jenny, who, as many of you will know, was an exceptional classroom teacher, but who, in my opinion, is an even more exceptional Teacher Librarian, and much of the foundational work on the FOSIL Group website that we still depend on was done by her. I would also like to thank the UK School Library Association, who have supported the work of the FOSIL Group through the FOSIL Group website since its foundation.

Perhaps most significantly for today, we would not be here except for a Principal of a school who understood that a fully human education required the library to be a unique kind of learning space, and the school librarian to be a unique kind of teacher. When I serendipitously wandered out of the classroom and into the library, Richard Blake and Jean Warwick created the conditions in which I could ask, and still continue to ask, what kind of learning space, and what kind of teacher? They created an enabling inquiry environment for me as an inquirer that continues to shape my work today, which is what I and we strive to do for students every day.

The earliest reference that I have to FOSIL is from 2010, which means that 2025 marks 15 years of thoughtful development of FOSIL, and since 2020 in weekly discussion with Barbara Stripling, whose work is foundational to FOSIL.

This brings me to the first major FOSIL development, which is the book that Barbara and I have been contracted to write for Bloomsbury Libraries Unlimited, titled, Teaching Inquiry as Conversation: Bringing Wonder to Life. This book, which we will finish by the end of August, enables us to draw our work together more closely, and to develop it more fully.

So, with the benefit of 15 years of hindsight, insight and foresight, what is FOSIL, bearing in mind that we understand inquiry to be a stance of wonder and puzzlement that leads to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community?

Firstly, FOSIL is an evolving response to the question, “What is school for?”

The answer to this question is neither as obvious nor as simple as it at first appears.

Jacques Maritain, who is proving to be especially helpful in this regard, considers that “the chief task of education is above all to … guide the evolving dynamism through which a person forms themself as a person” (1943/ 1971, p. 1), or, in other words, to enable our students to realise their full potential as human beings in relation to each other in the world.

This requires them to know and understand things about the world and themselves and each other, to be sure, but it also requires them to be able to come to know and understand those things, or, in other words, to know how to acquire knowledge and understanding of those things, and many more besides. This is more than mere memorisation and reproduction.

Secondly, then, FOSIL is an evolving response to the question, “How does school enable this human awakening in a coherent way?”

For Maritain, “education is fully human education only when it is a [contemporary] liberal education, preparing the youth to exercise their power to think in a genuinely free and liberating manner — that is to say, when it equips them for truth and makes them capable of judging according to the worth of evidence, of enjoying truth and beauty for their own sake, and of advancing, when they have become adults, toward wisdom and some understanding of those things which bring to them intimations of immortality” (1962/ 1967, pp. 47-48).

A distinguishing feature of a contemporary liberal education is inquiry, especially in the form of Signature Work (AAC&U, 2020), which is a learning stance and process, encapsulated by C.S. Peirce (1955) in his first, and in one sense only, rule of reason: “In order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so doing not be satisfied with what you already incline to think” (p. 4).

Inquiry, then, in forms appropriate to its subject matter, is responsible for what we know and understand about the world as reflected in the various disciplinary bodies of knowledge that cohere into a meaningful and interdisciplinary whole. This is why inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning matters, because inquiry is fundamentally how we come to know and understand the world and ourselves in it – reality – which is the basis for responsible participation in community, and which is ultimately the only true measure of human success.

Consequently, as Maritain (1952, p. 3) puts it: “Nothing is more important than the events which occur within that invisible universe which is the mind of [a person]. And the light of that universe is knowledge. If we are concerned with the future of civilization we must be concerned primarily with a genuine understanding of what knowledge is, its value, its degrees, and how it can foster the inner unity of the human being.”

Viewing and approaching the acquisition of knowledge in this way, and to this end, requires purposeful and effectual collaboration between classroom-based teachers and library-based teachers. The library is, after all, as Douglas Knight (1968) reflected, a uniquely creative meeting place for minds and ideas, and then the active extension of those ideas in the minds of our students, which depends for this essential function on the vital collaboration between those who teach the mind to inquire and those who teach the mind how to inquire (pp. vi-ix).

Thirdly, then, FOSIL is an evolving community of inquiry formed in response to the question, “What, in my specific educational context, does inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning look like?” My response to the question – FOSIL – led eventually to the formation of the FOSIL Group in 2019, which is a shared approach to this educational imperative, and is what brings us together today. The response to this question, however, is broader than FOSIL. I have already mentioned my debt to Barbara, whose Empire State Information Fluency Continuum is distinct from FOSIL, even though they have essential features in common, and who brings today’s proceedings to a close. I am equally delighted that Dianne and Jennifer opened proceedings today, because their deeply thoughtful and highly influential Alberta Model of Inquiry, which is central to Focus on Inquiry: A Teacher’s Guide to Implementing Inquiry-based Learning was formative for me and is indicative of the FOSIL Group’s broader concern with inquiry (see Focus on Inquiry in the FOSIL Group Forum, and also E&L Memo 2 | Focus on Inquiry: Reflections on Developing a Model of Inquiry by Dianne). It is worth noting that Stripling’s Model of Inquiry (2003), which is central to the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, FOSIL (2010), and the Alberta Inquiry Model (2004) account for three of the five models included in the IFLA / De Gruyter book, Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (2022).

This brings me to the second major FOSIL development, which is the foundation of the [school-based] Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry [in PK-12 education].

Jonathan Rauch, in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (2021), highlights how our existential crisis is epistemological in nature – a breakdown in the knowledge-building process, which is the inquiry process. The Constitution of Knowledge – liberal democracy’s “epistemic operating system: our social rules for turning disagreement into knowledge” – depends on the vitality of a “reality-based community of error-seeking inquirers” (p. 15). This community has been severely weakened by the almost total failure of schools to equip students for their role in strengthening this community, a failure to enable inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning in PK-12 education. And it is precisely because school “is the one institution in our society that is inflicted on [almost] everybody,” that Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner (1969/ 1971) forewarned that “what happens in school makes a difference – for good or ill” (p. 12).

As today demonstrates, concern with these questions, and responses worthy of our serious consideration, is broader than FOSIL. This is healthy, and is the rationale for the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry, which is to support and provoke thoughtful effort to enable inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning in PK-12 education regardless of model, and this for the purpose of developing a reality-based community of engaged and empowered inquirers.

This brings me to the third major FOSIL development, which is the Creative Commons reconceptualization of the Heroic Inquiry Cycle for a contemporary liberal education, which I first developed with Hugh Rose at Blanchelande College in 2021. Hugh and I will share this later.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.