Academic Honesty and FOSIL

Home › Forums › Skills, skills frameworks and stages in the FOSIL Cycle › Academic Honesty and FOSIL

Tagged: Academic Honesty, copyright, Secondary

- This topic has 2 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated 6 years, 7 months ago by

John Royce.

John Royce.

-

AuthorPosts

-

28th June 2019 at 1:09 pm #1661

I am trying to work out where Academic Honesty in all its facets sits within FOSIL. As an IB school it is vital that we tackle the issue from the very beginning of our students’ time with us. My inclination is that is spans a number of facets of the cycle – Investigate, Construct, Express and Reflect. Does anyone consider this to be part of the framework or is it outside in your view? Does it matter? 😉

We begin to teach referencing using Harvard from term 1, Year 7 and I am thinking or using a peer marking method to ask students to assess each others’ academic honesty in Year 8 as a reinforcement tool? Any thoughts, is this too harsh?

Ruth

3rd July 2019 at 8:46 am #1918Thanks for this excellent and important question, Ruth.

Citing and referencing is explicitly part of the Express stage, which is consistent with other models of the inquiry process and information literacy definitions; i.e., it is when sharing what I have found that acknowledging my intellectual and informational debt to others is formally required. In fact, our journey to FOSIL started with a search for a framework of information literacy skills that would help us to actually prepare our students for the IB DP EE requirements for students to cite and reference according to a recognised academic style. The Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, which fortuitously turned out to be a framework of inquiry skills and accompanying model of the inquiry process, locates citing and referencing at the following points in the framework:

- Year 11: “Cites all sources used according to standard style formats”. We chose APA for the EE for a number of reasons.

- Year 8: “Cites all sources used according to local style formats”. We chose APA as our house style for the same reasons and for consistency.

- Year: 6: “Cites all sources used according to model provided by teacher” (includes librarian). As above.

However, because the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, which FOSIL grew out of, is aimed at “building understanding and creating new knowledge through inquiry”, there is a concern with sources that runs through the entire Cycle:

- Connect: What do I already know, which may require some investigation, and how certain am I of this knowledge?

- Wonder: What don’t I know and/or what am I not certain of, and where might I find this out?

- Investigate: We tried to make the concern with sources explicit in the description of this stage – “Knowing what scholarly resources are available and being able to use them effectively”.

- Construct: While all of the stages are important, this stage is crucial as it shifts the emphasis from finding information to thinking with the information. Interestingly, because the emphasis is on what students think about the information that they have found in response to their informational need, so theirconcern with the intelligibility and reliability of their sources is slowly growing, and so is their desire to point his out. This is addressing academic honesty in a proactive and positive way. Also, we tried to make the concern with sources explicit in the description of this stage – “Building an accurate understanding based on factual evidence”.

- Express. This is where citing and referencing is explicitly located. It is worth pointing out here that when we first started, most colleagues viewed citing and referencing as a technical skill, and there is a technical element to it, but it is more properly an academic skill – working with other people’s ideas and information – that students need to be taught and given opportunities to practice in in all academic disciplines (subjects). In our experience, most cases of academic dishonesty are a consequence of students lacking proficiency in this academic skill (especially if their preparation for the EE has been GCSEs). The majority of colleagues are now starting to recognize this, and again, this is addressing academic honesty in a proactive and positive way. Also, we tried to make the concern with sources explicit in the description of this stage – “Making the most compelling case given your evidence and audience”.

- Reflect. As a reflection on the process and outcome, a concern with academic honesty is implicit.

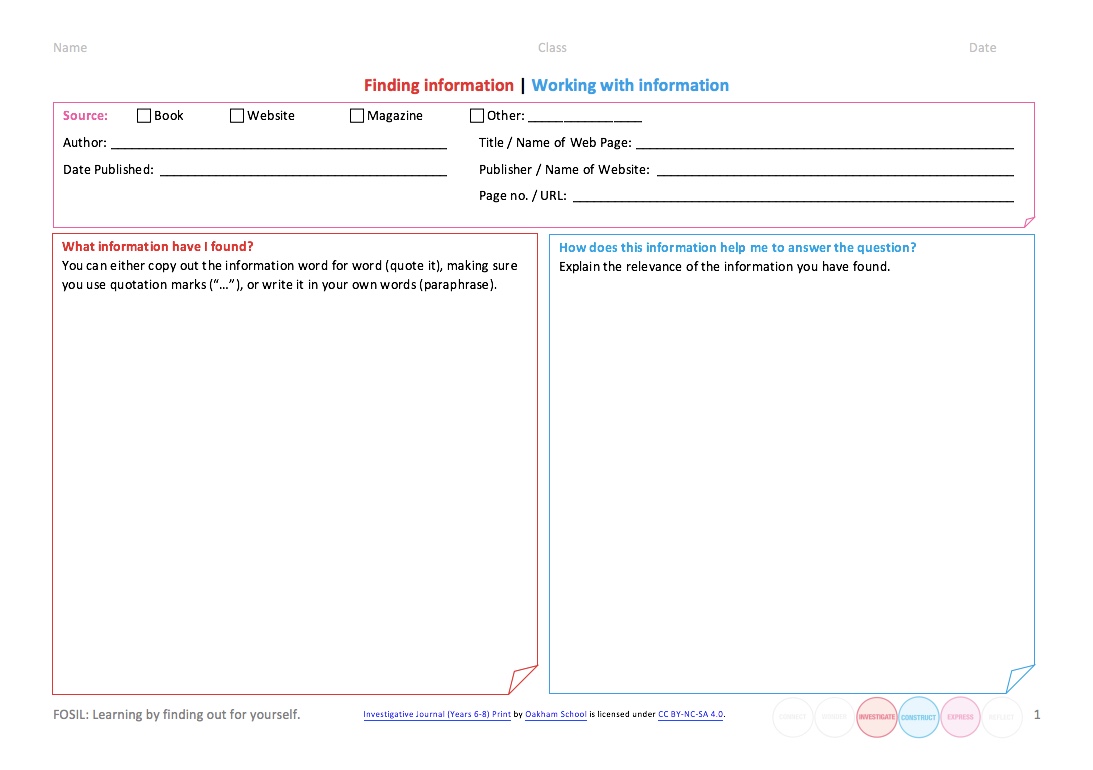

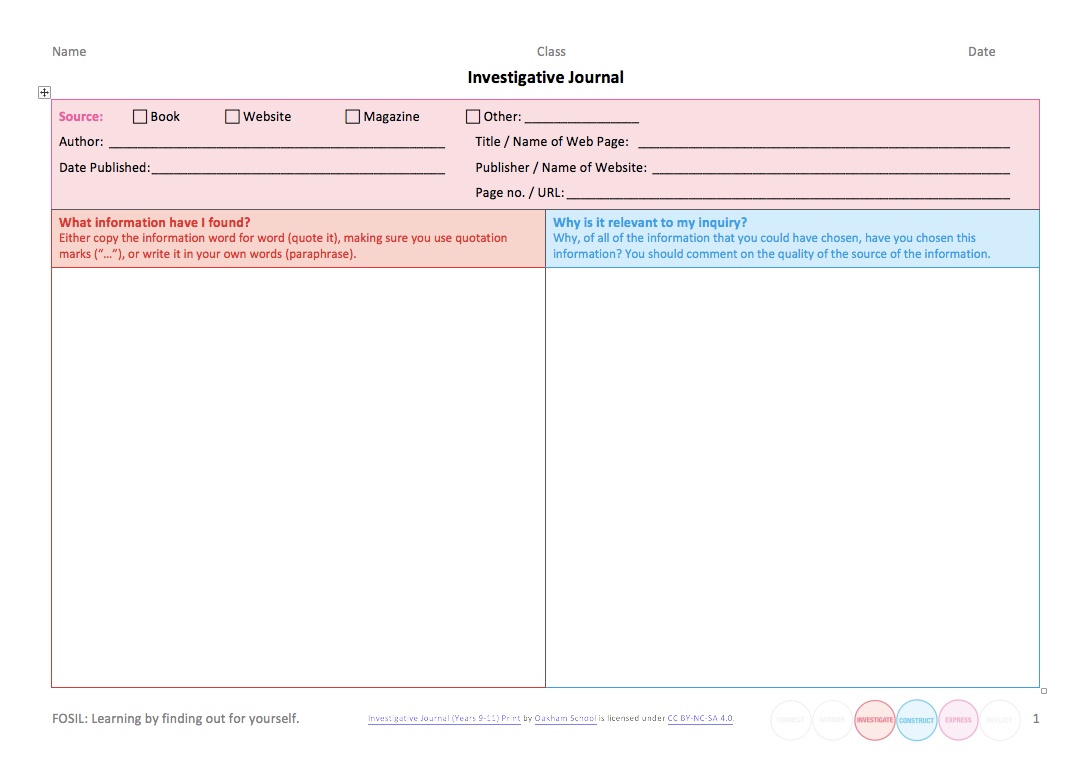

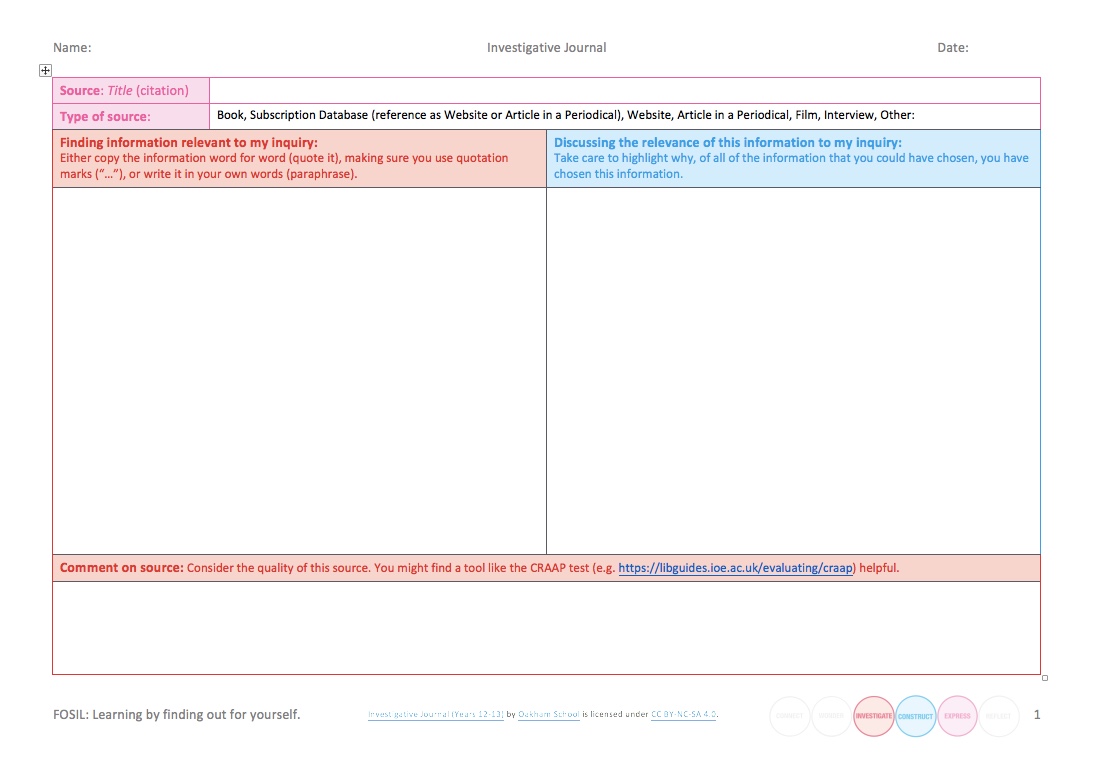

More concretely, the resources that we have been developing to enable the stages in the process make this concern with academic honesty explicit and unavoidable. The most obvious example is the Investigative Journal (follow link for downloadable versions of our current Lower School – Years 6-8, Middle School – Years 9-11, and Upper School – Years 12-13, versions. Images below.), which is designed to help students think (Construct) with the information that they have found (Investigate). However, as they will need to formally cite and reference their sources (Express), this is included in the Investigative Journal. This is having the effect of slowly normalizing this complex behavior from Year 6 through to Year 13, as well as for colleagues, and, again, this is addressing academic honesty in a proactive and positive way.

As for the peer marking, I think that this is an excellent idea, especially if the focus is on assessing [and rewarding] the quality of each other’s sources rather than ‘catching each other out’ for academic dishonesty, which I think is a small but significant shift in emphasis with far-reaching consequences.

Darryl

3rd July 2019 at 5:06 pm #1967

3rd July 2019 at 5:06 pm #1967Ruth, I’m with Darryl here, citing and referencing feature at every stage of the research and writing process.

I hold that academic honesty is only a very small part of the reasons for citing and referencing and as such it comes out in the actual writing (or other form of presentation), in the Express stage. Even here, there are other reasons for citing and referencing, from showing the breadth of your investigation to showing who you know the key writers in your topic are, from helping readers follow and understand your journey and themselves obtain (some of) the sources you found useful to demonstrating your worthiness to be a part of the academic conversation and the academic community. (That last is where “correctness” of formatting of citations and references comes in – and mistakes in the correctness of the formatting do not necessarily equate with academic dishonesty.). And there are other reasons too, few of which connect with (academic) honesty but are totally about academic writing.

I am a strong supporter of note cards and/or research journals so that, even in the earliest stages of the cycle, the researcher has a record of sites and articles read or viewed, along with notes of what might be significant and/or usable and a record of the elements which together will inform the reference if the researcher decides to use it. The note cards or research journals can take any form or format, maybe several, but they make for memory-joggers and enables retrieval of the original if closer reading is needed at a later stage of the investigation. And maybe not the current investigation but a later and a different one. As the investigation progresses, the research journal or cards could be in constant use.

When noting the bibliographic details in these early stages, correctness of formatting does not come into it – as long as the writer provides a reminder for him/herself of where the material was found, and at least enough information to allow the writer to find it again.

In the presearch stage, the exploration stage of a research project, the connecting, wondering, investigating stages especially, one is reading widely so making notes, making connections, raising questions … so that when it comes to the closer reading of the construction and expression stages, one has ready-made reminders of what to look at more closely and what you will find useful in the actual writing/ presentation.

I agree with Darryl – using peer review to consider the quality of the sources and not just the notional “correctness” of the references can be useful. As can asking the peer reviewer to retrieve the sources based on the information given and checking for completeness.

Not harsh at all, Ruth, starting as early as you can, inculcating good habits so that honesty becomes engrained.

One other thought – academic honesty is not simply about citing (and referencing) – and in this sense it again features at every part of the FOSIL cycle. There are other aspects of research and writing in which honesty and academic should be the norm, the expectation, the requirement – else the integrity of the work (and thus of the writer) is at risk.

John

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.