Reading for Inquiry Learning

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Reading for Inquiry Learning

Tagged: reading

- This topic has 16 replies, 6 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 10 months ago by

Olga Nesi.

Olga Nesi.

-

AuthorPosts

-

21st February 2020 at 8:49 am #39015

I have created this Topic – 17 March 2021 – to draw the various discussions about reading together.

Inquiry is a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society.

This process is dependent to a surprisingly large extent on reading in the very broadest sense of the term, and so is not limited to informational texts/ reading.

The first 10 posts in this Topic were moved here from the Topic called Knowledge and Reading, which has now been deleted.

Subsequent posts, starting with this one, have been moved here from Reflecting on E&L Memo 1 with Barbara Stripling.

21st February 2020 at 8:49 am #4091I had the pleasure of spending the better part of a week with Annie Everall – CILIP School Libraries Group (SLG) Conference Organiser – at the IFLA 2019 World Library and Information Congress in Athens. A topic of much discussion was reading for learning from information, a discussion that resulted in a keynote at the SLG National Conference 2020 – Shaping Their Futures.

My description of the keynote, which I needed to submit in October 2019, looked like this:

Enabling understanding through reading: the development of a reading mind | The FOSIL Group

According to Saul Bellow in his Foreword to The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom, Balzac declared that the world belonged to him because he understood it. This means that the world and the fullness of its possibilities is open to our students to the extent that they understand how it works, or closed to them to the extent that they don’t. Our role in their reading journey from information through knowledge to understanding is a complex one, and the focus of this keynote.

As this is a very important topic, and a complex one, I had always intended to involve members of the FOSIL Group who I could learn from, colleagues such as Alice Visser-Furay. Alice ( @AVisserFuray) is the Literacy Coordinator and Reading Intervention Specialist at King Alfred’s Academy in Wantage, Oxfordshire. I first made contact with Alice after she shared her Literacy key questions and strategies 2019-202 on Twitter (this now also features on Alice’s excellent website – Reading for Pleasure and Progress). What struck me, from the perspective of a school librarian, was Alice’s emphasis on academic reading [for progress] in addition to her emphasis on reading for pleasure, as well as how highly regarded she is for her work on developing both. This made Alice the obvious choice for the keynote, and I am delighted that she agreed.

Alice introduces herself in the Staff/Common Room here.

I am also delighted that Alice has agreed to think through the keynote with me in the Forum, because an important function of the Forum is to make the thought behind what we do explicit to the benefit of the community – as Doug Engelbart said, the better we get at getting better, the faster we will get better. So please join us in the discussion.

To get things going I share the following from Reading nonfiction : notice & note stances, signposts, and strategies (2016, Beers & Probst, p. 4):

A stance is required for the attentive, productive reading of nonfiction. It’s a mindset that is open and receptive but not gullible. It encourages questioning the text but also one’s own assumptions, preconceptions, and possibly misconceptions. This mindset urges the reader both to draw upon what they do know and to acknowledge what they don’t know. And it asks the reader to make a responsible decision about whether a text has helped them confirm prior beliefs and thoughts or had enabled them to modify and sharpen them, or perhaps to abandon them and change their mind entirely.

This is so much more than getting children to read and/or like reading, and strikes me as more even than just developing their ability to read. Where to begin?

21st February 2020 at 10:37 am #4095Thank you to Darryl for inviting me to speak at the SLG conference. I very much look forward to exploring the development of the reading mind with Darryl and anyone else on the forum.

I am delighted that Darryl’s first volley was Reading Nonfiction by Beers & Probst; the book that first got me thinking about the reading mind, especially in the context of struggling readers, is called When Kids Can’t Read, What Teachers Can Do and it is by Kylene Beers (2002). This book has been a metaphorical bible for me as a teacher and intervention specialist looking for ways to improve the academic and life chances of students.

Beers and Probst have another book, Disrupted Thinking: Why How We Read Matters (2017). In it, they talk about reading as more than retrieval and extraction; they advocate interaction with text – teaching students how to read with curiosity, how to ask questions and how to let what they read change them. They conclude by stating (p. 162):

Perhaps, therefore, the most important thing we do with children is to ask them to consider how they might have revised their thinking as a result of reading. ‘How has this book or story touched you, made you think again about who you are or what you value? How has this text changed your thinking?’

As educators, we need to teach students how to develop the ability to allow text to ‘disrupt’ thinking – and we need to provide a multitude of opportunities for them to engage with challenging fiction and non-fiction from a variety of viewpoints. In our keynote, I am hoping that we can provide practical strategies that librarians, leaders and teachers can use to develop the reading mind.

2nd May 2020 at 7:39 am #4428So much has happened in 2 months, including the already-postponed SLG National Conference being postponed until 2021.

Unfortunately Disrupted Thinking: Why How We Read Matters is in lockdown, but I have Reading Nonfiction. In it Beers & Probst share the following haunting bit of a lesson they heard from a teacher (pp. 5-6):

This teacher, burdened by constraints he felt from his district, had set aside what he told us were best practices to instead use “test practices that I know will show the administration I did all I could to get kids ready for the almighty test.” So, his lesson on a topic (any topic will do) basically followed this pattern:

- Show students an interest-building clip on the topic from the web.

- Tell kids what they need to know about the topic. They take notes.

- Have some discussion on the topic.

- Give kids a test on the topic.

Show. Tell. Discuss. Do you notice what is missing? Where’s the reading kids do to learn about the topic? When we asked the teacher that question, he pointed out that when he begins his series of lectures about the topic (lectures lasting from one day to several weeks), he often has short articles from the web up on the whiteboard for all to read. We asked him if that was enough reading to help students become savvy readers of nonfiction. He stared at us for a moment and then responded that “the textbook is worthless, and frankly I don’t have time for kids to read in class. And they don’t want to read. They don’t care about the topics we discuss, so if I gave them something to read, if they did anything it would be just a surface-level reading.” We asked if he assigned reading for home. “Are you kidding?” he replied. “They wouldn’t do it.” Then he asked us, “So, if you were trying to get kids into reading some nonfiction, how would you do it?“

Beers & Probst then go on to write a book about this. However, their context is, arguably, different. So, if you were trying to get kids into reading some nonfiction, how would you do it, given that I’m guessing many teachers here would consider themselves to be in a similar situation to the teacher Beers & Probst describe?

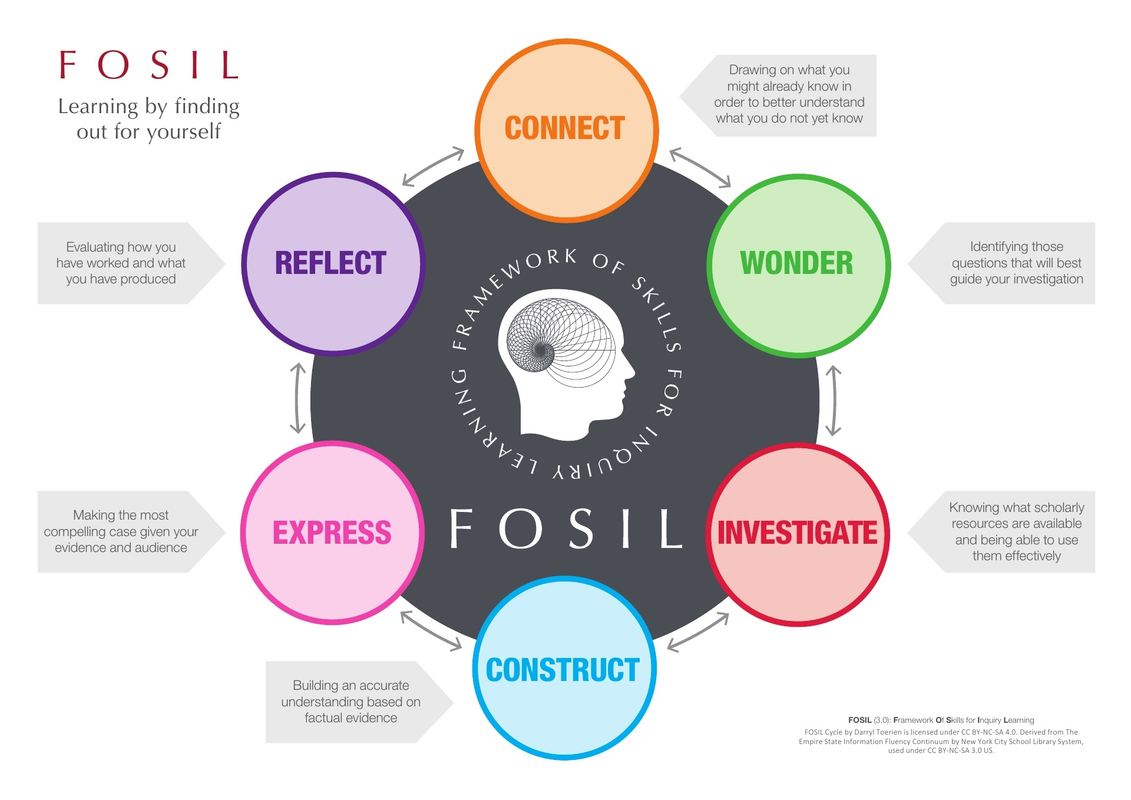

From my perspective as a school librarian, who was once a classroom teacher, reading is fundamental to the student’s “information-to-knowledge journey”, which, in turn, is fundamental to the definition of the school library (IFLA School Library Guidelines, p. 16). From the perspective of FOSIL as a model of the inquiry process (see below), reading is fundamental to Connect (establishing what you know, or think you know), Investigate (finding reliable information) and Construct (making sense of that information in order to build on what you know). From the perspective of FOSIL as a continuum of inquiry skills that enable the inquiry process (see below), reading is fundamental to many, if not most, of these skills.

How, then, we collaborate with teachers to make time for the progressive and systematic development of a reading mind within the curriculum is of vital importance, and I look forward to your thoughts.

22nd May 2020 at 7:27 am #4458

22nd May 2020 at 7:27 am #4458I have been reading through this discussion with interest due to a couple of planned webinars I am running on the 2nd and 9th of June around Literacy and Reading Promotion. I have found it very useful to read that ‘reading for information’ is equally important as ‘reading for pleasure’ as this is where I want to focus my session. I feel that school librarians need to understand that literacy comes in all forms and not just fiction and as I begin to bring my ideas together for these webinars I look forward to discussing my thoughts with you both.

24th May 2020 at 7:34 am #4463I just wanted to share my thought process so far. Literacy and Reading Promotion within the IFLA School Library Guidelines does very much follow the traditional pattern within the ‘normal’ school of thought. With the librarian’s role in creating good diverse library collections, book talks, library displays, special events, book awards and book events and I will start my webinar talking about this.

However, I have found both of these within the guidelines:-

“A school library operates as a…literacy centre where the school community nurtures reading and interact development in all its forms,” which I feel gives me justification to move onto ‘reading for learning’ and…

Reading and literacy capabilities: “abilities and dispositions related to the enjoyment of reading, reading for pleasure, reading for learning across multiple platforms, and the transformation, communication and dissemination of text in its multiple forms and modes to enable the development of meaning and understanding.”

Both of these quotes gives me the opportunity to talk about the school librarian’s role in reading within subjects… Alex Quigley’s book Closing the Reading Gap has a chapter on it which I was going to use.

Do you think this is a good connection and how much time should I send on the first part? I am open to any ideas 🙂

25th May 2020 at 6:32 am #4465There are two things that I think are worth highlighting in relation to the IFLA School Library Guidelines in this regard.

Firstly literacy and reading promotion needs to be approached from the definition of a school library, which is “a school’s physical and digital learning space where reading, inquiry, research, thinking, imagination, and creativity are central to students’ information-to-knowledge journey and to their personal, social, and cultural growth” (p. 16). There are 3 elements to this definition:

- The school library is a physical and digital learning space, in which …

- … reading, inquiry, research, thinking, imagination, and creativity are all means to an end …

- … which is the information-to-knowledge journey and personal, social, and cultural growth of students.

It is important to root the discussion about reading for pleasure and reading for learning in this definition, I think, because the information-to-knowledge journey is simply not possible without reading, and this reading must be what you are calling reading for learning (although reading for pleasure can contribute to this journey). It is also worth noting that the definition lists reading along with inquiry, research, thinking, imagination, and creativity, but in reality it is difficult to imagine those activities separated from reading, even if only indirectly.

Secondly, “school library services include … [a] vibrant literature/reading program for academic achievement and personal enjoyment and enrichment” (p. 19). This states explicitly that the librarian’s role includes both reading for learning and reading for pleasure.

If by first part you mean establishing a case for reading for pleasure and reading for learning, then I don’t think that you can afford to rush this.

Also, what might a vibrant literature/reading program for academic achievement, rather than personal enjoyment and enrichment (which we, as librarians, are very comfortable with), look like?

I’m very interested to see where this part of the discussion leads.

26th May 2020 at 4:06 pm #4468Thanks for this Darryl. I will put some thought to your ideas and ask again when I am stuck…

Alice I wonder if you can point me in the right direction

I am looking for national standards in literacy and reading. Is there something that I can link within the Education government department that talks about expected standards in both pleasure and learning. Or does such a thing not exist?

10th June 2020 at 3:15 pm #4486I don’t know if Alice, Darryl, Elizabeth or anyone else in the Forum can help. I’ve been thinking about the aspects of literacy pupils require to be able to successfully ‘decode’ a question in my subject (science). It seems to me that as questions in UK science examinations become increasingly wordy, the gap between those pupils who can quickly understand what a question is asking and those who can’t is widening.

This skill of decoding an exam question is subtly different to disciplinary literacy or content area literacy, I think. Is there a particular pedagogical term for it, or a body of knowledge that might help?

(Shanahan and Shanahan make the distinction between disciplinary literacy and content area literacy thus: Content area literacy focuses on study skills that can be used to help students learn from subject matter specific texts. Disciplinary literacy, in contrast, is an emphasis on the knowledge and abilities possessed by those who create, communicate, and use knowledge within the disciplines. (Shanahan, T. & Shanahan, C. (2012). What Is Disciplinary Literacy and Why Does It Matter? Topics in Language Disorders, 32 (1), pp. 7–18).

11th June 2020 at 8:18 pm #4489A really interesting question Chris… I shared it on twitter and had this response and thought I would share it with you…

“Not only understanding the context of what’s being asked of you, but understanding the context of what’s being expected from your answer, which is often subject-specific. Often the answer needs to conform to standards unique to the discipline within which you’re being tested”

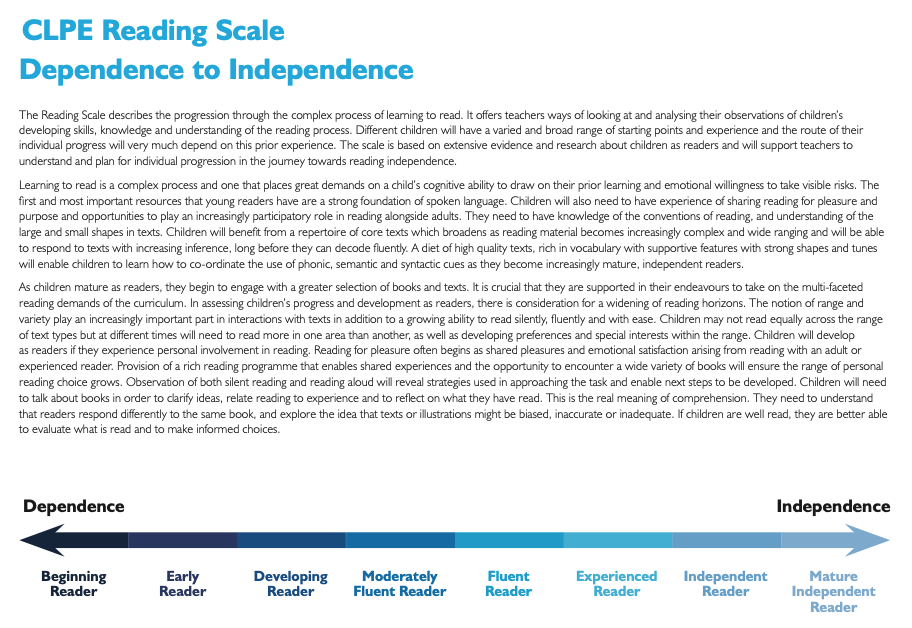

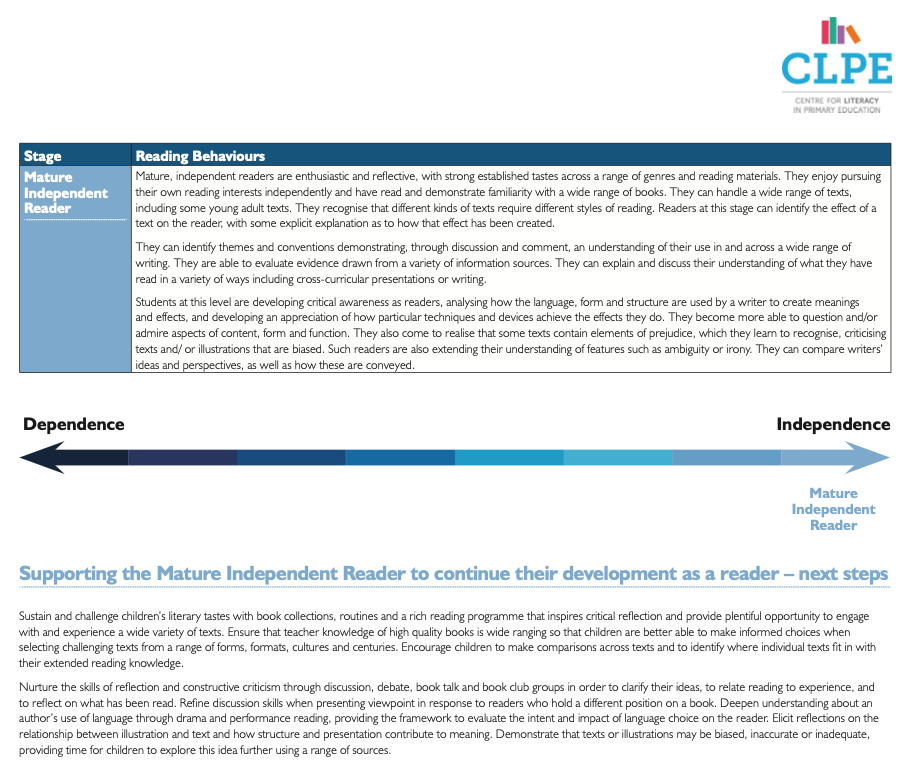

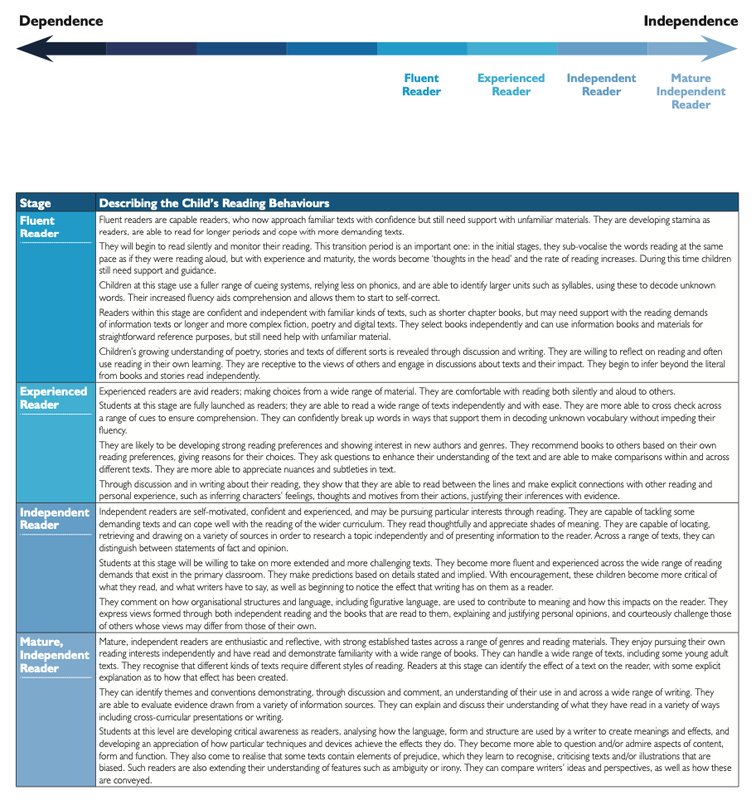

20th June 2020 at 7:02 am #4515Chris, I came across the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education, a UK based children’s literacy charity working with primary schools, although their Reading and Writing Scales, which are available as PDF downloads for free, support “progression for 3-16 year olds in a 21st Century Classroom. … The CLPE Reading and Writing Scales describe the journey that children make in order to become literate. … The pedagogy underpinning the scales and the Next Steps is grounded in a coherent theory of children’s language and literacy development, exemplified by the research element of this document, a review of current relevant research.”

The fact that the CLPE provides a wide range of professional literacy training at an affordable price [aimed at Reception, Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2] suggests that this is not part of teacher education and training. If that is the case, it would be interesting, and perhaps telling, to know what along these lines is.

Having not yet had a chance to look at the Reading Scale (24 pages) carefully, it appears to describe “the observable behaviours of pupils at different stages” – from Beginning Reader to Mature Independent Reader – as well as describing “the provision, practice and pedagogy a teacher would want to plan for in order to help the child move forward in their literacy.”

My initial thoughts in relation to your post are:

- The language of the descriptors, especially towards the upper end of the scale, seems to address your concern to some extent and, perhaps, lays a foundation for content area literacy and/ or disciplinary literacy.

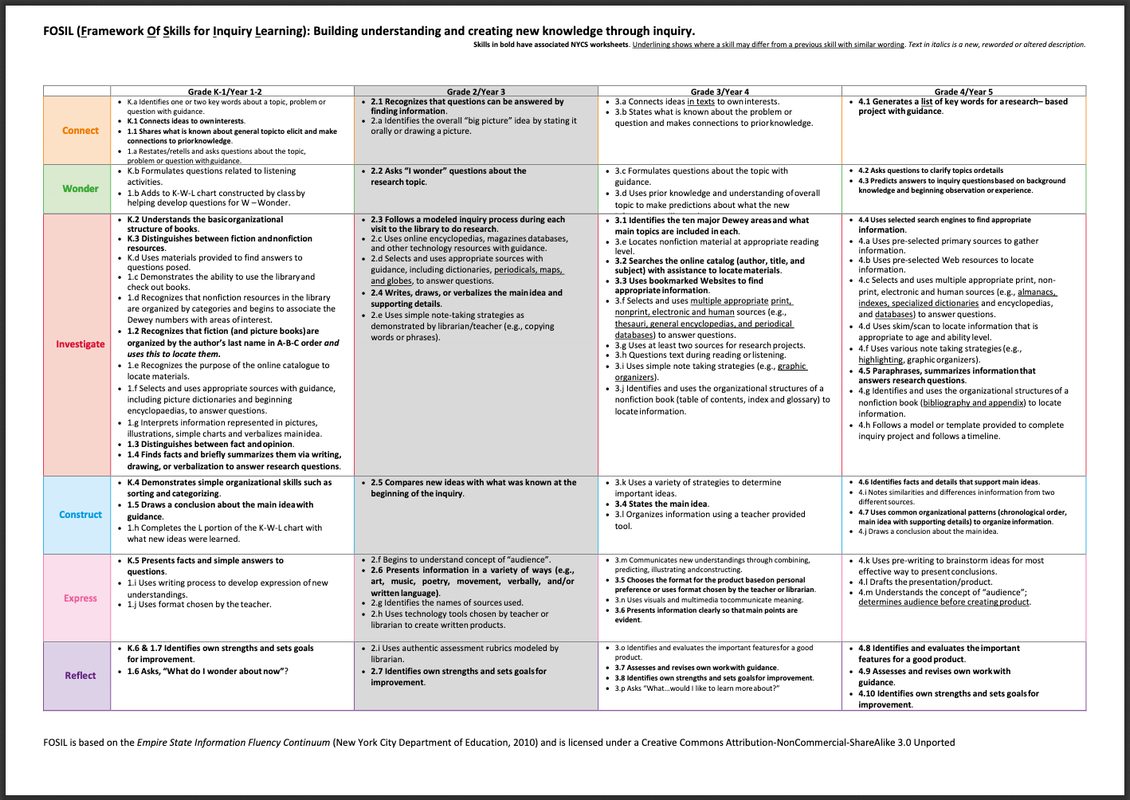

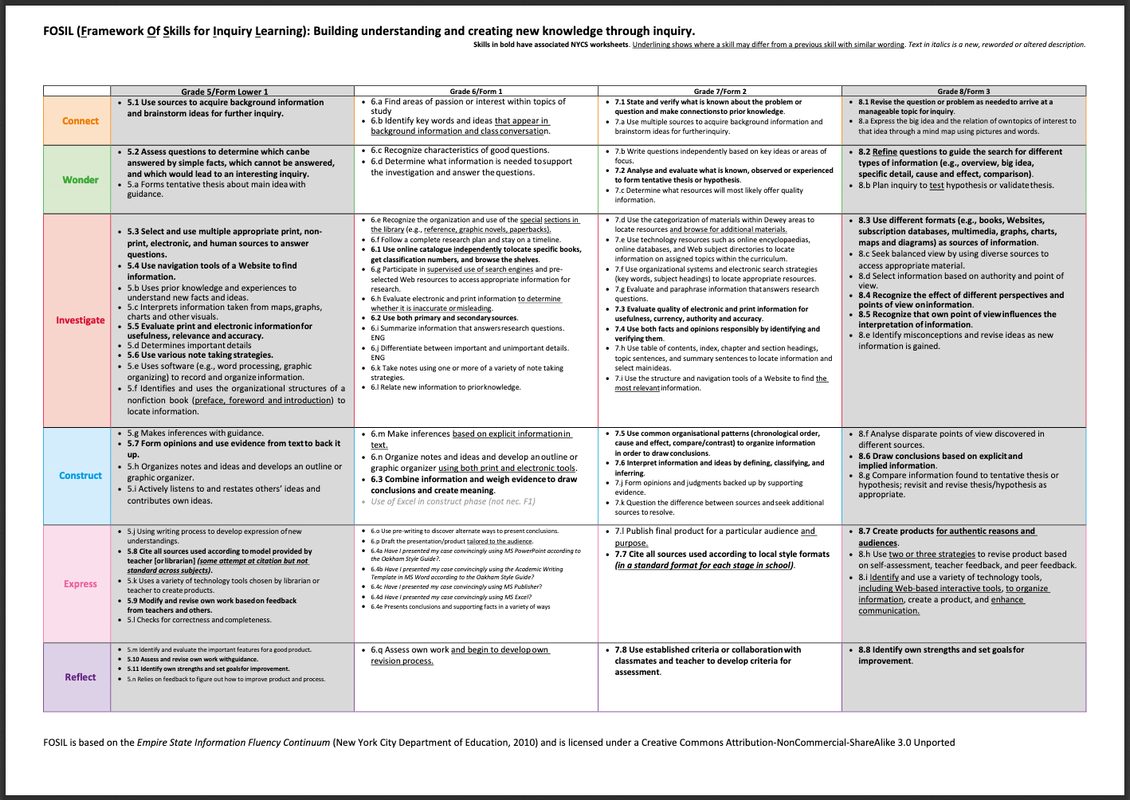

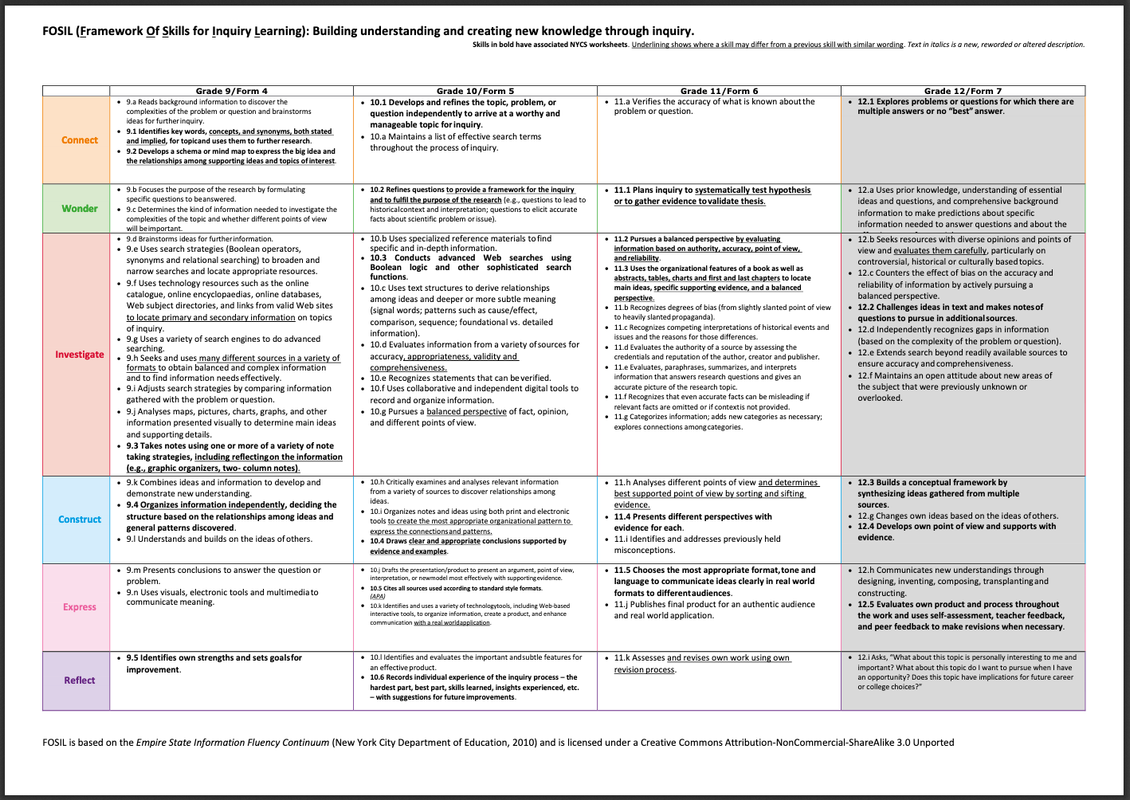

- The focus of the scale seems only to be on identifying where on the scale individual students fall and the next steps in moving them on. Like with our discussion about the IB Middle Years Programme (MYP) ATL (Approaches to Learning) skills, which we need to return to, there doesn’t appear to be any sense of how these skills ought to be developed progressively and systematically from year to year. However, and as with the MYP ATL skills, the FOSIL inquiry skills continuum above – and the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (ESIFC) more broadly that this is based on – includes these skills to a greater or lesser extent. This potentially means that we could view the scale through the lens of FOSIL, which would add a layer of value to our integration of FOSIL with the MYP ATL skill categories/ clusters (which we also need to return to). As I am in the process of mapping the 2019 ESIFC, I will see if I can find some good examples to illustrate this.

- The “review of current relevant research” might be particularly useful to you.

Hopefully this goes some way towards answering your questions.

4th February 2021 at 11:30 am #35642[Edit: This discussion about reading follows on and was moved from the discussion of what each phase of the inquiry cycle adds to the intellectual experience of our students – see this post]

Thank you for broadening this out, which is a timely reminder that we serve, in the terms of the IFLA School Library Guidelines and IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto, an educational purpose – improving teaching and learning for all – and a moral purpose – making a difference in the lives of young people. While these terms require some unpacking, inquiry – understood as a dynamic process and stance aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community – is essential to fulfilling these purposes.

At the risk of oversimplifying, knowledge is built from information, which comes to us either directly though experience or, especially in the context of school, indirectly through recorded experience (mainly secondary, but also primary). Norman Beswick (1967), in making this point also, helpfully, reminds us to be broad-minded about what constitutes a record: “some knowledge, truly, comes from experience and experiment; most knowledge from record, in the widest McLuhan-like sense” (p. 201).

This record includes but is not limited to the library’s collections, which should reflect, as Julian Astle and Laura Partridge (2018, p. 10) so eloquently put it in Education for enlightenment, “the great conversation of mankind – the unending dialogue between the living, the dead and the yet-to-be-born … the best that has been thought, said and done,” and our task, then, is to “equip [our children] to appreciate it, interrogate it, apply it and build on it” through inquiry. It should be noted that it is this conversation, or more precisely the content of this conversation, that is of fundamental concern to us, and not the records, or resources, themselves.

Entering into this conversation remains more or less dependent on reading – “in the widest McLuhan-like sense” – from within an inquiry process and stance. Consequently, a greater understanding of the role of reading, and literacy more broadly, in the inquiry process becomes vital.

How might we start describing this role of reading, and literacy more broadly, in the inquiry process?

—

References

- Astle, J., & Partridge, L. (2018). Education for enlightenment. In A. Painter (Ed.), Ideas for a 21st century enlightenment (pp. 10-15). London: RSA Action and Research Centre.

- Beswick, N. W. (1967). The ‘Library-College’ – the ‘True University’? The Library Association Record, 198-202.

20th February 2021 at 5:59 pm #36726I have been reflecting lately on the role of reading, and more broadly literacy, in enabling learners to make sense of themselves and the world. The superficial type of reading fostered by the digital environment and the preponderance of misinformation and even disinformation have put me on high alert. I am worried about the tendency of both adults and young people to dart from one site or source to another, processing little beyond graphics and headlines, ignoring any text that is too complex or challenging, and believing anything they “read.” If my goal is to enable students to become independent learners with an inquiry stance on the world, then it is my responsibility to integrate the teaching of deep reading skills into my teaching of inquiry.

To provoke my own thinking, I recently read Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World by Maryanne Wolf. Although Wolf’s focus is reading, I engaged with the book through my lens of inquiry. I tried to translate Wolf’s ideas about digital reading into the types of reading and the skills that I thought would be most important at each phase of inquiry. It’s been an interesting process. I have certainly deepened my understanding of the skills that students need to be able to develop their own ideas, interpretations, and conclusions throughout the process of inquiry. I share my thoughts below in the hope that others will push back, question, and add to my ideas about integrating deep reading with inquiry.

Connect. The Connect phase of inquiry has probably been impacted more than any other phase by my new understanding of deep reading skills. Originally, I envisioned students engaged in overview activities, like listing what they think they already know about the topic and gathering background knowledge of the main ideas, people, dates of the overall topic. In my mind, Connect was largely an intellectual experience. By adding deep reading strategies, Connect can be transformed into a highly personal, relevant, and meaningful start to an inquiry experience. I would teach students to identify their own feelings and assumptions about the topic, read laterally to discover multiple perspectives, determine the importance of information, create a conceptual map of major ideas and overall context, and discover aspects of the topic that are personally interesting or evocative.

Wonder. Wonder questions are usually generated from the internal and external connections that students make during the Connect phase. Teaching the strategy of questioning the text will facilitate the development of questions that students are motivated to pursue through inquiry: challenging the ideas in text (Why?, What if?, So what?); extending the ideas in text (What else is important?, Whose voices are missing?); and connecting to their own personal interests (Why do I care about this?, What intrigues me?).

Investigate. An important reading strategy to enable students to pursue deep meaning and not just bits of information during their investigations is interactive reading. Two-column notetaking provides a template for students to think about the information they are noting and respond in the right column with questions, challenges, opinions, and emotional reactions. Many students find their investigations challenging because they lose focus, get frustrated, or get overwhelmed. We can teach reading self-management skills to help students overcome their challenges: maintaining focus by setting a daily limited learning target, using question-based notetaking strategies, continuous self-monitoring of comprehension and interpretation; and maintaining a research log of reflections on their progress. Wolf reminded me that both deep reading and inquiry require “cognitive patience,” or the time, persistence, and open mind to think deeply and let new ideas percolate.

Construct. Students should be engaged in reflective reading during Construct to facilitate combining their internal knowledge (experiences, feelings, interpretations) with their external knowledge (information they have acquired during their investigation, their responses to that information) to form new understandings. Several skills of reflective reading are particularly valuable for students during Construct: perspective taking (empathy), or understanding another’s perspectives, feelings, and actions; challenging their own thinking by questioning their own interpretations and conclusions; and what Wolf calls “reading for the narrative,” or looking for the conceptual whole that brings all of the new ideas together into a new understanding that makes sense.

Express. Imagination is an important component of deep reading that is essential during the Express phase. Students can use creative thinking to envision, develop, and present expressions of their learning that convey multiple layers of meaning – new understandings and the supporting evidence, personal interpretations and conclusions, and the personal passions and self-confidence that developed during the whole inquiry experience.

Reflect. The deep reading strategy of reflection should permeate the entire inquiry experience, but the final reflection presents the opportunity for students to solidify their inquiry stance. When students reflect on their inquiry process and product, they recognize their own strengths and challenges in engaging in academic and personal learning. They develop agency and self-confidence to adopt an inquiry stance as a way of interacting with the world.

I recognize that this reflection on the power of integrating deep reading strategies into inquiry is aspirational. I am thinking about the vision I want to achieve for all our students. Now, we must all engage in the hard work of figuring out how to bring this vision to life in our schools.

Wolf, Maryanne. Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. NY: Harper, 2018.

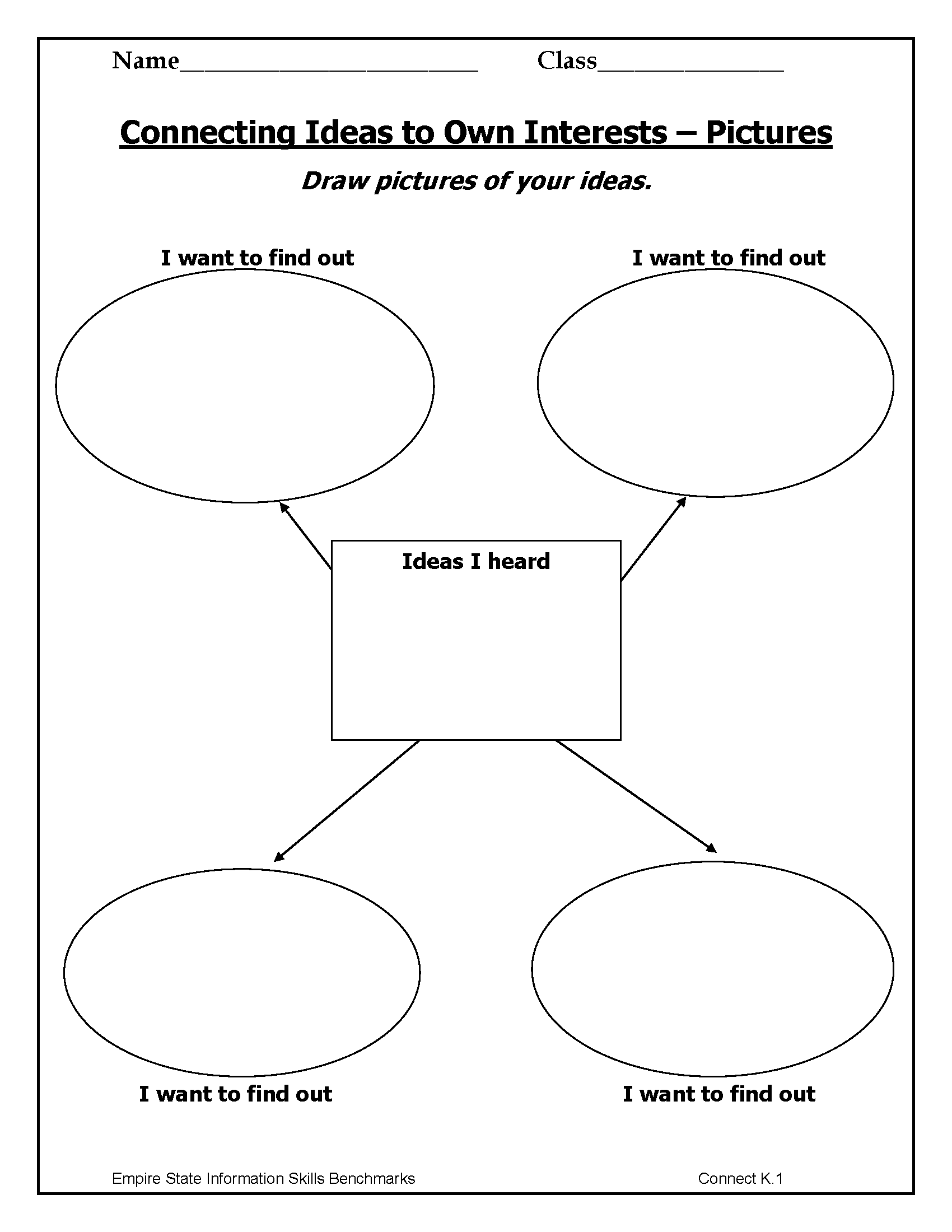

11th March 2021 at 3:25 pm #38064I recognize the importance of teaching deep reading skills as a part of inquiry, but I also know the power of enabling the development of deep reading whenever and whatever our students are reading – from stories to websites to personal explorations to inquiry. As a part my work in 2018 to develop a PK-12 information fluency continuum (adopted throughout New York State and called the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum – ESIFC) (https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc), I created a large body of graphic organizers to guide students’ independent practice for each of the priority skills in the continuum. I have selected a few that I thought would be particularly relevant to the teaching of deep reading skills. Excerpts of those graphic organizers are below, but the full, Word versions can be downloaded free from the above site. I have included the identifying numbers of the graphic organizers for your convenience.

Connect. A foundation of deep reading is the reader’s ability to make connections between the text and his own interests, prior knowledge, and questions. We can start with early elementary children by enabling them to connect ideas to their own interests (K.1).

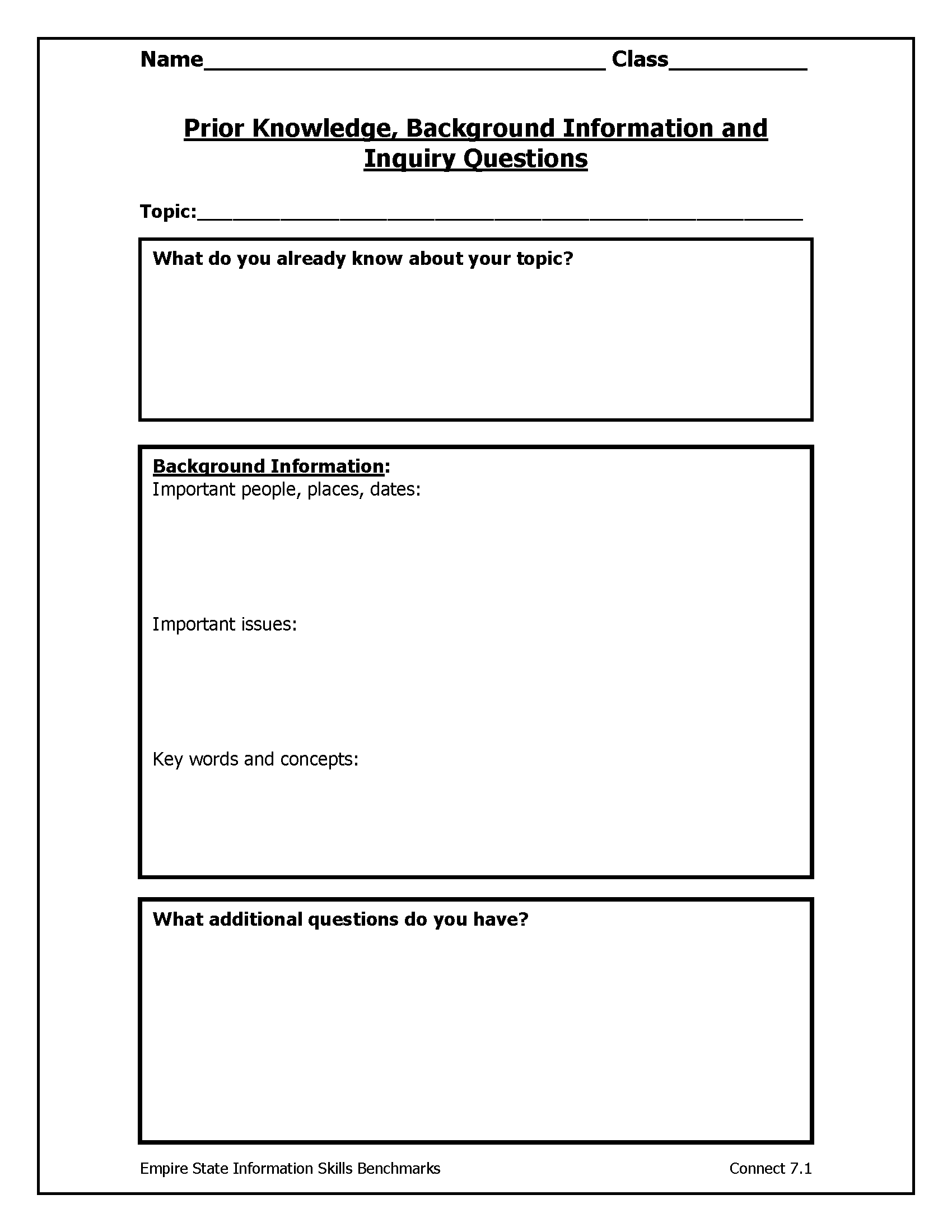

By the time students are in middle school, we can teach students to use their own prior knowledge and the background information they have gained to start asking inquiry questions (7.1).

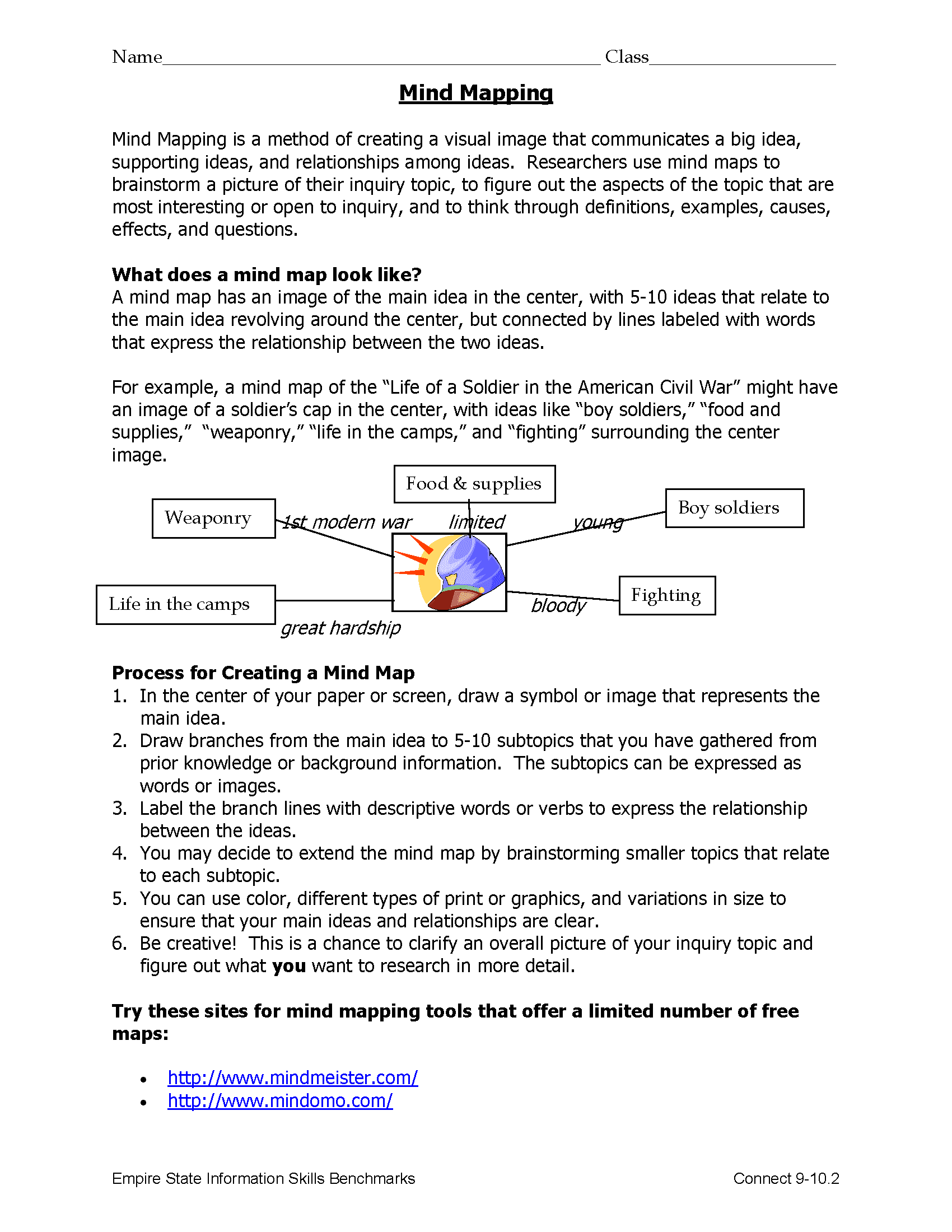

One of the important aspects of the Connect phase is for students to gain an overview picture of the whole idea, so that they can keep that context in mind when they select their focused topic for research. Librarians can develop a mind map with the whole class, with students contributing the ideas they have gained through their own reading or prior experience and the class deciding how the ideas fit together into a larger picture. Older adolescents can be taught to perform the complex reading skill of concept mapping independently (9-10.2).

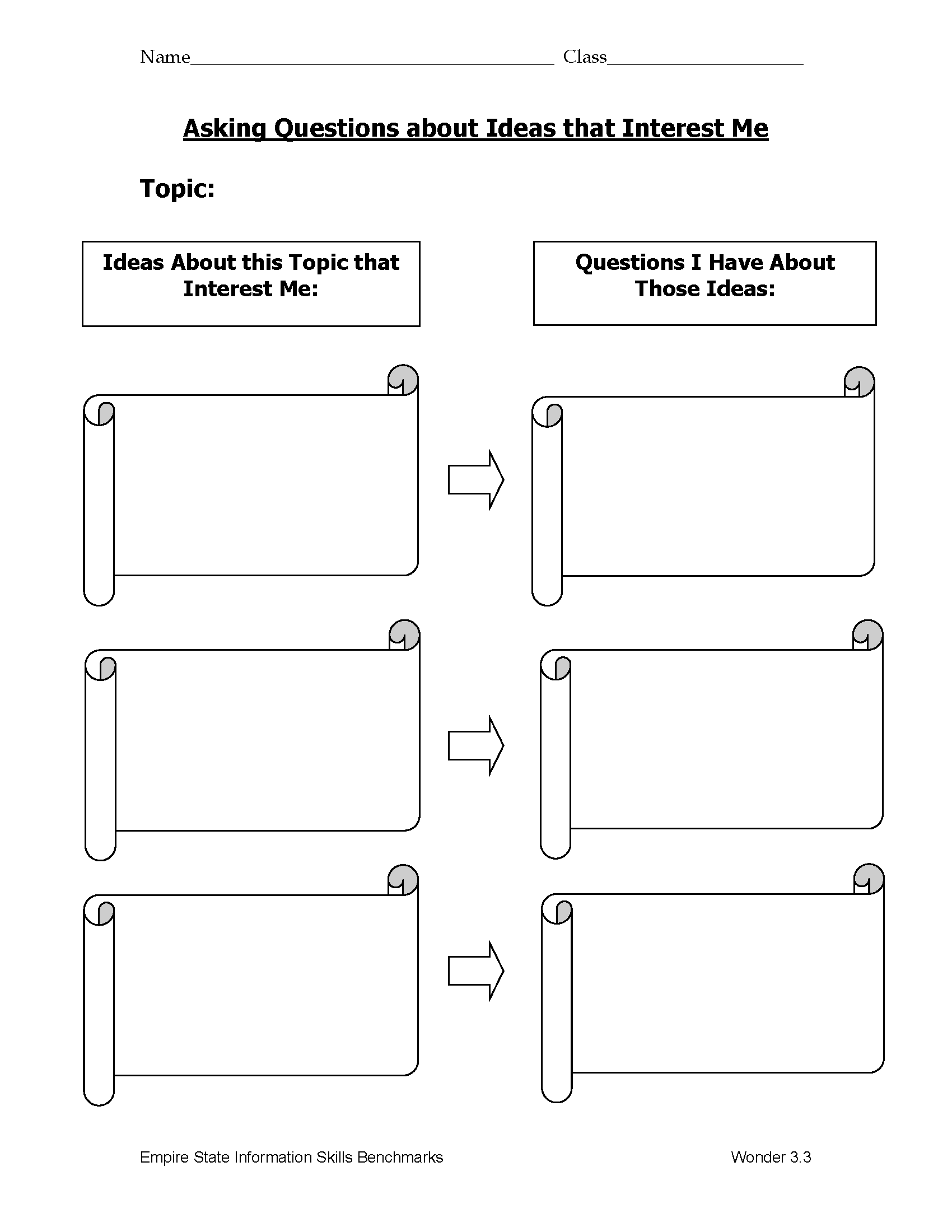

Wonder. Two of the deep reading strategies that enable students to develop Wonder questions that they are motivated to pursue are 1) to make sure that their questions emerge from a personal area of interest (3.3)

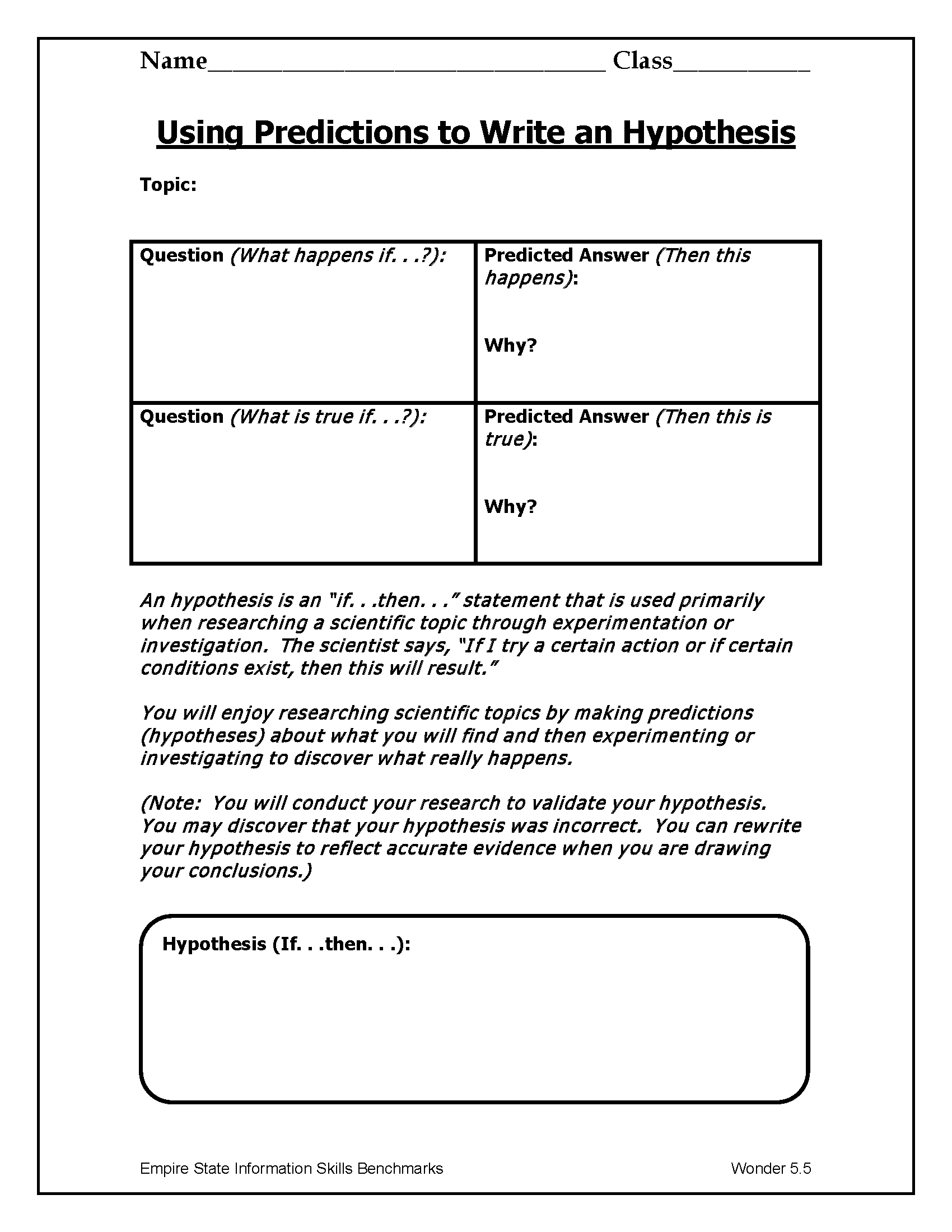

and 2) to guide them in predicting the answers they might find (and even to form an hypothesis based on their predictions) (5.5).

Reading experts have shared that, when students are personally invested and looking for answers to their questions as they read, they are more likely to read for meaning beyond simple comprehension of the text.

Investigate. Reading plays a prominent role during Investigate in any inquiry experience. The challenge for librarians is to teach students to interact with the text (in any format), to draw meaning that goes deeper than simply copying information, and to question, evaluate, and challenge the evidence they discover. The number of deep reading skills and strategies to be used during Investigate is quite large, but I have selected four skills that may not be as familiar to many librarians.

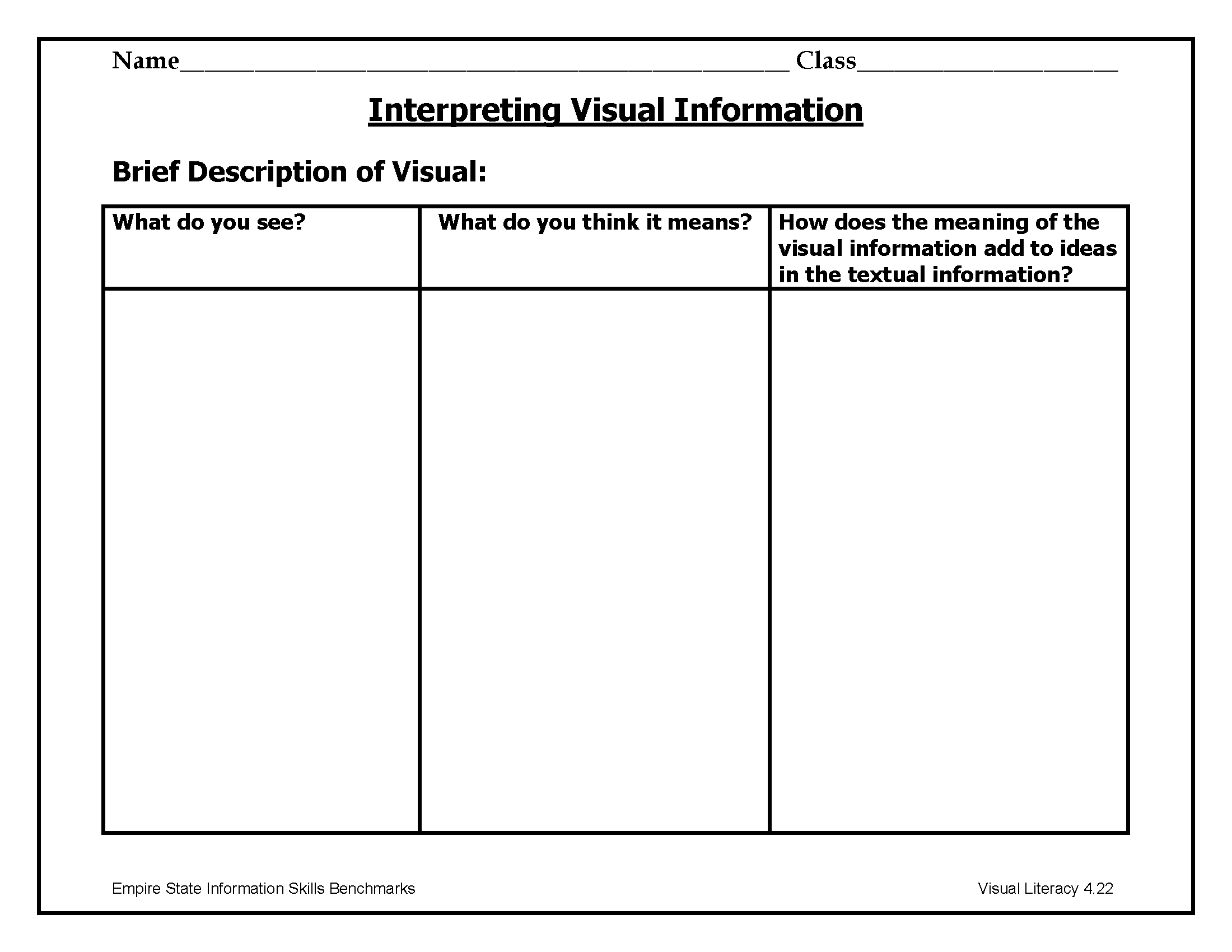

Much valuable information and alternative perspectives are offered through visualizations, including graphics, photos, art, political cartoons, and all forms of media. Students do not necessarily respond thoughtfully to visuals. Teaching that skill can start in early elementary (by drawing meaning from story book illustrations, for example) and can build in sophistication over the grades. The following graphic organizer could be to teach elementary students to interpret visual information (4.22).

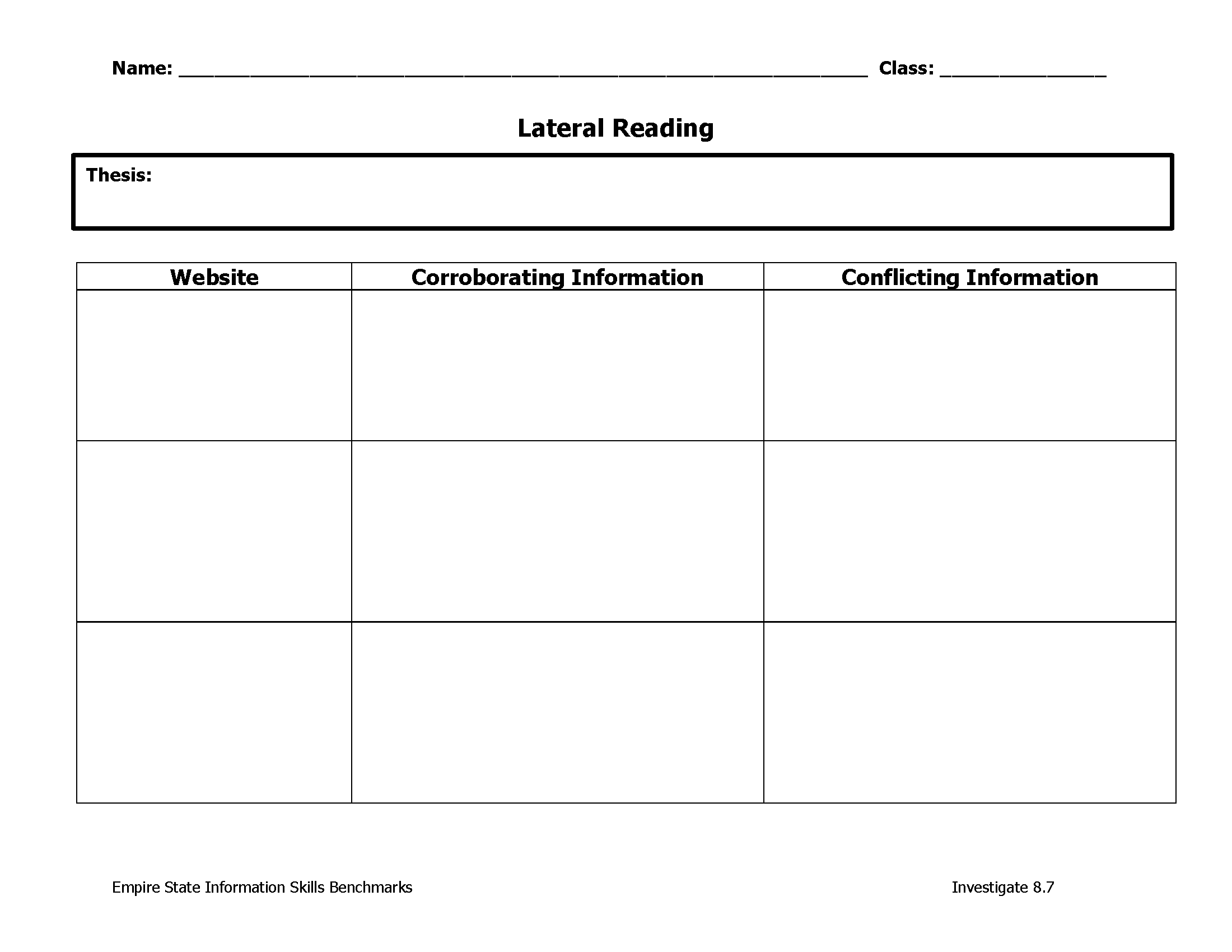

By the time students are in middle school, they should be expected to check their own inquiry process by making sure that they have been open to corroborating and conflicting information, rather than simply finding only information that confirmed their prior assumptions or their favored point of view. Teaching the strategies of lateral reading will strengthen and deepen their investigations (8.7).

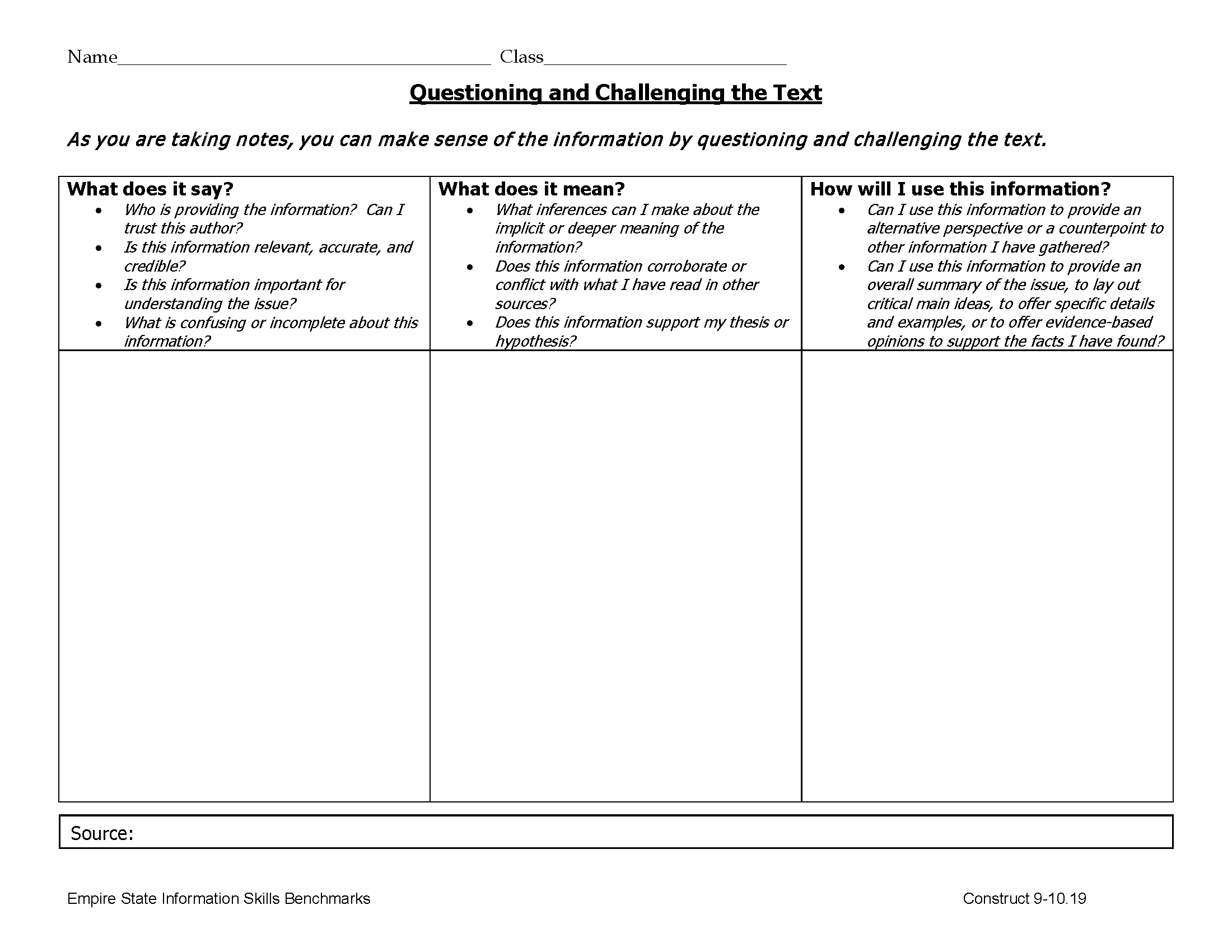

An important deep reading skill, to question and challenge the text, is honestly one of the most difficult to make a permanent habit of mind, for adults as well as young people. Often the time pressures of assignment due dates will lead to cursory reading and quick fact accumulation. Expecting students to take notes in a graphic-organizer format that is designed to generate reflection and questioning is an effective way to build deep reading and thoughtfulness into investigations. The graphic organizer below is one example that librarians might use (9-10.19).

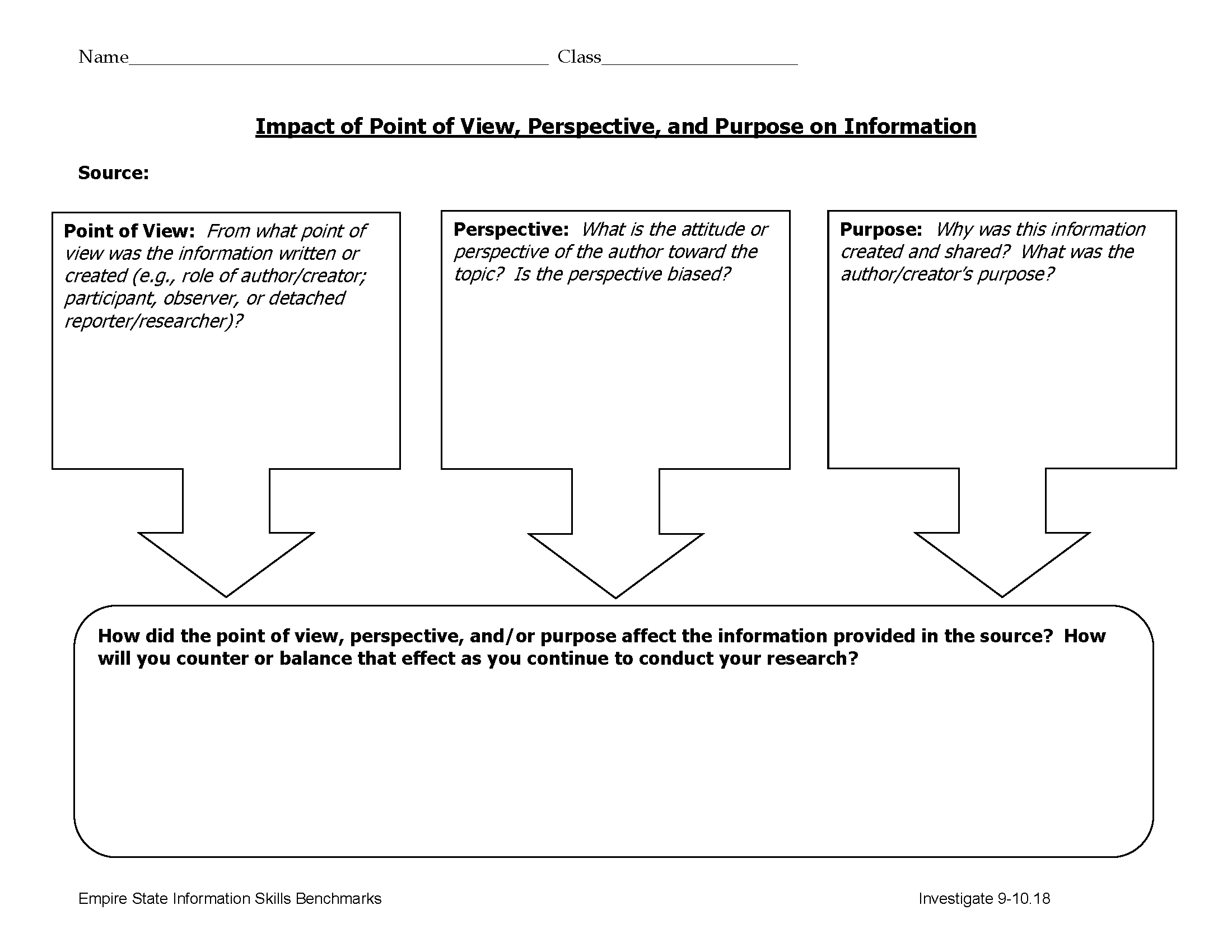

From the earliest moments in school, young people need to start identifying point of view in text that they read (or have read to them). Elementary students might start by looking at the point of view of characters in a story. These students must learn to transfer that skill to nonfiction texts during their inquiry investigations. By the time that students are in secondary school, they can be taught to assess the impact of point of view, perspective, and purpose on the information itself (9-10.18).

Construct. Although students may not be reading any new texts during the Construct phase when they are developing their own opinions and conclusions, they are re-reading their notes and perhaps sections of the sources they found most critical to their investigations. Reflective reading at this stage involves synthesizing the evidence they have discovered with the thoughts, opinions, feelings, and meanings that they have formed in response to the evidence.

When I first started focusing on inquiry, both as a stance and as a process for learning, I remember simply telling my students to draw their own conclusions after they had found the information they needed. When I saw my students struggling, I realized that the deep reading and inquiry skills of Construct must be taught explicitly. Students may be able to form opinions naturally, but those are not opinions based on careful assessment of the evidence. I had to teach students how to construct their own ideas and understandings based on their investigations and their careful analysis.

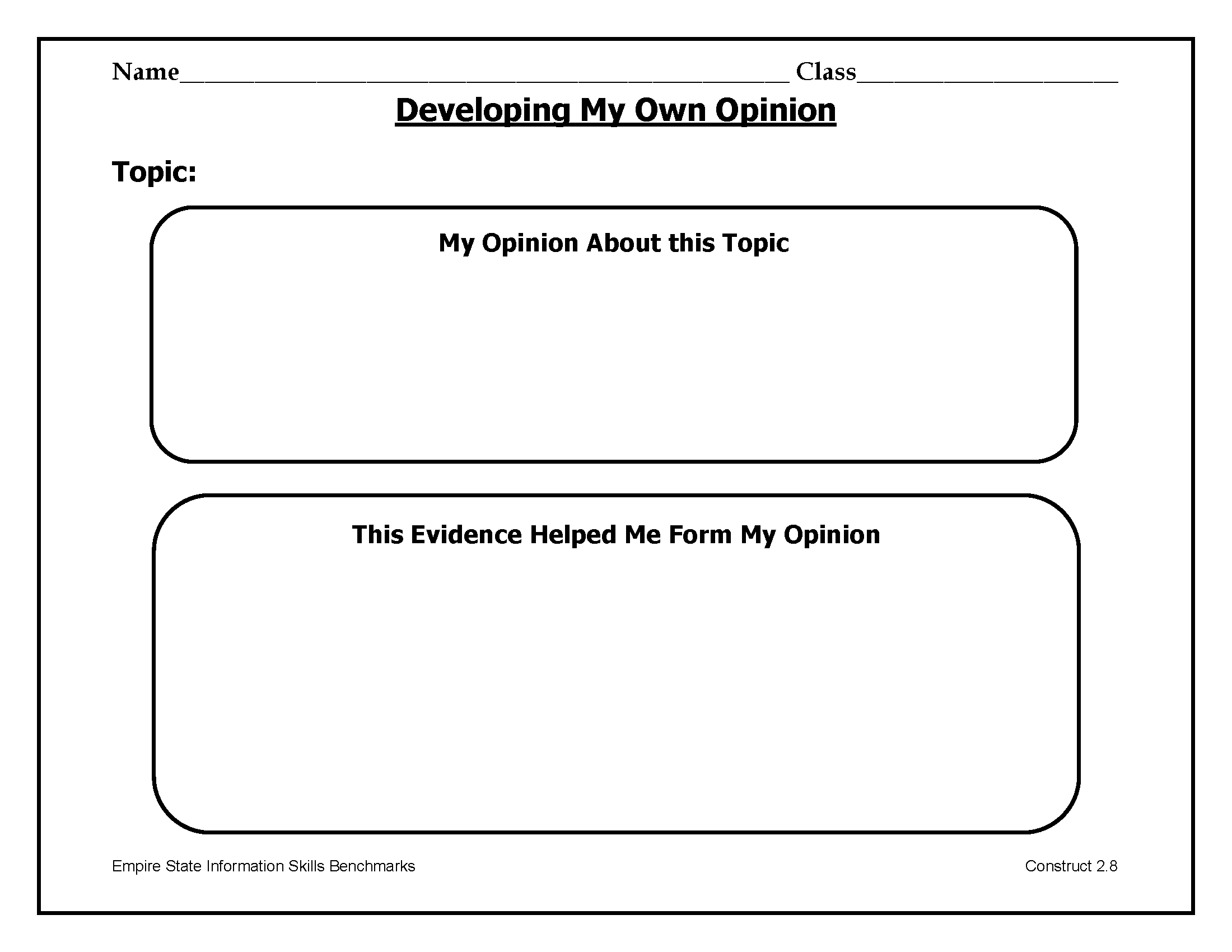

Young students can be taught to form their own opinions in early elementary. The essential piece is that they must tie their opinions to the evidence they have heard or discovered (2.8).

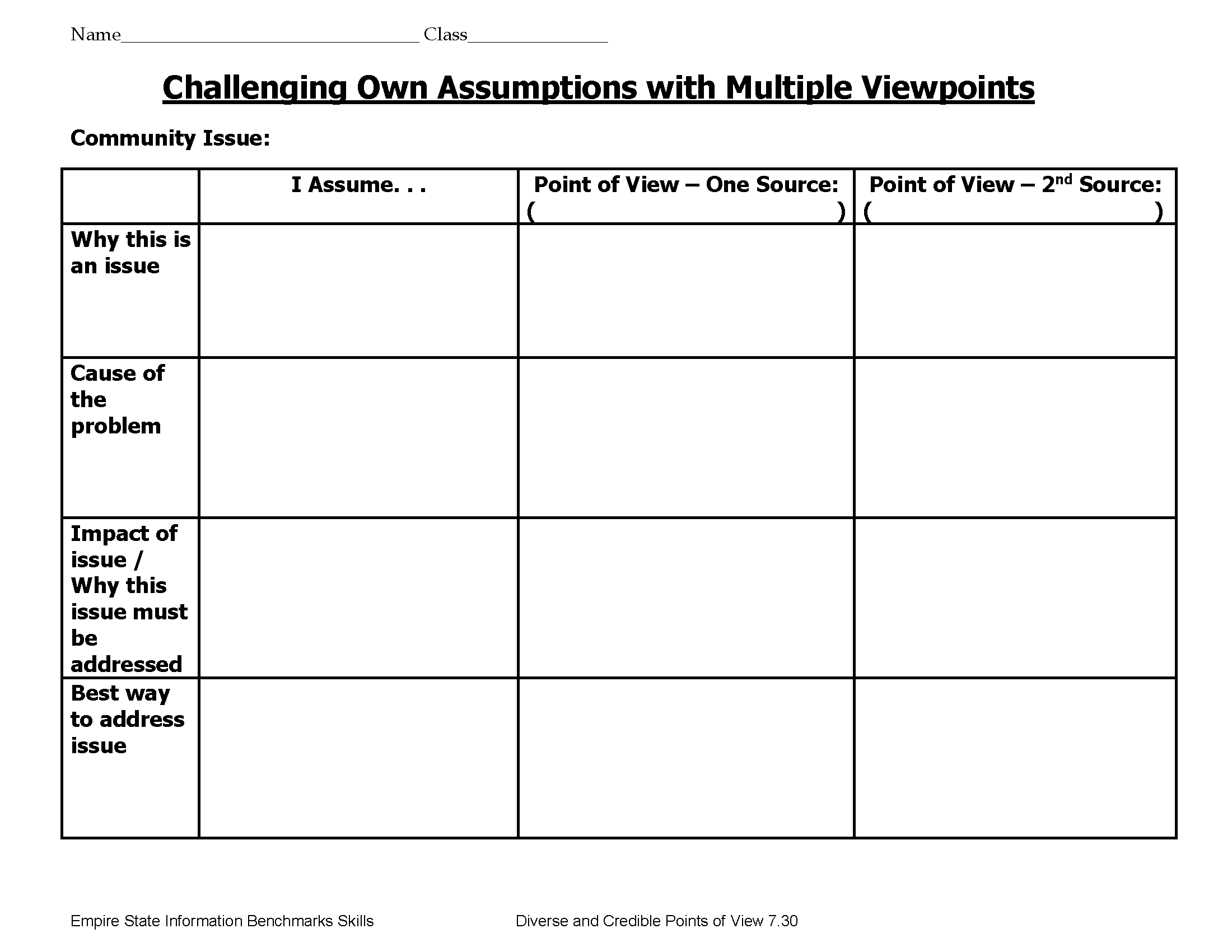

By the time students are in middle school, they should be expected to identify their own assumptions and challenge them by considering multiple viewpoints (7.30). Direct instruction on how to identify the viewpoint or perspective of a text, plus graphic organizers to guide them through the analysis process, will enable students to construct their own understandings based on evidence.

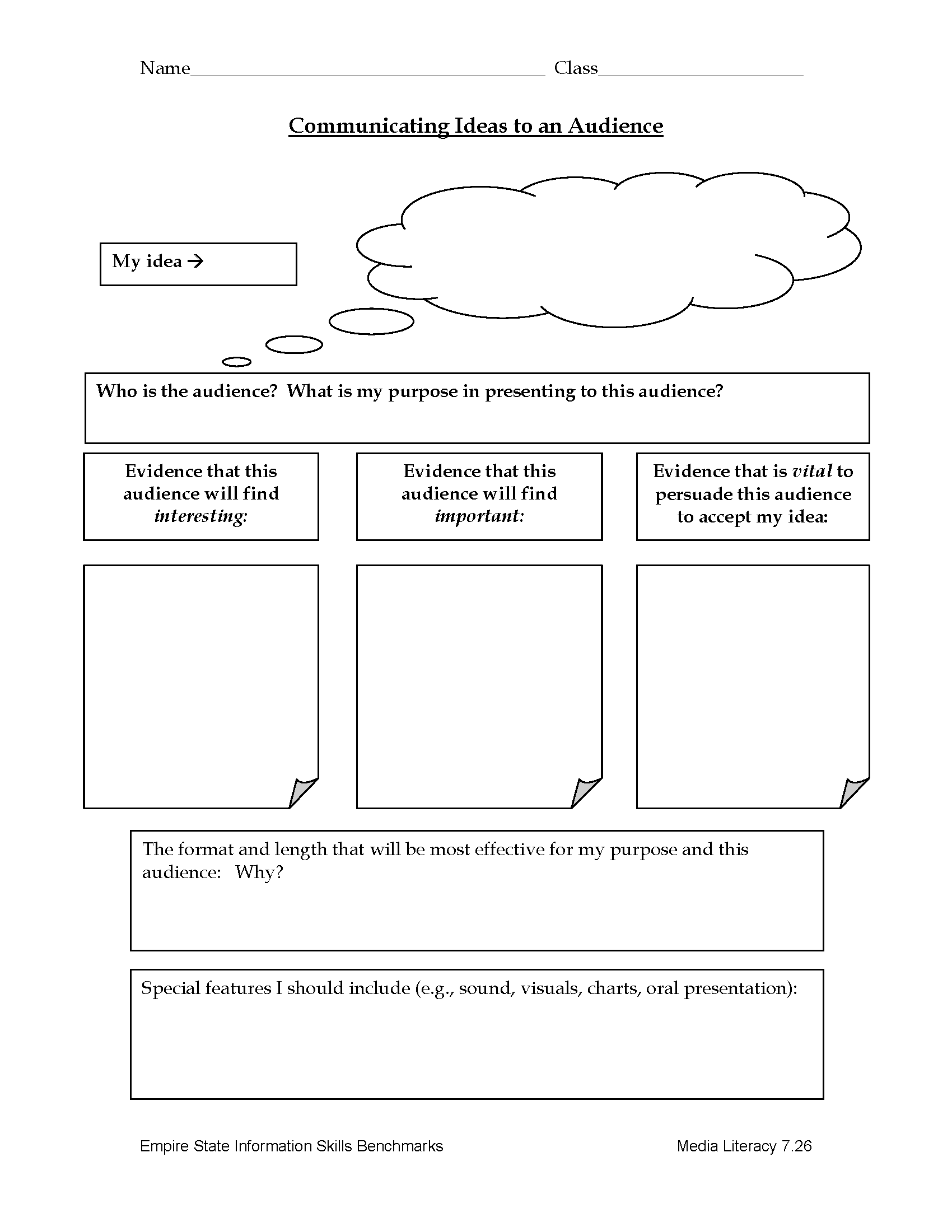

Express. A broad interpretation of deep reading skills at the Express phase includes teaching students to use language and other communication tools to create and share expressions of their new understandings. As leaders of inquiry for the whole school, librarians are in an excellent position to assume responsibility for teaching students the creation and presentation skills that will be relevant whenever they have the opportunity to share their learning. One communication skill that is rarely taught is “reading” an audience and tailoring a presentation to appeal to that audience (7.26).

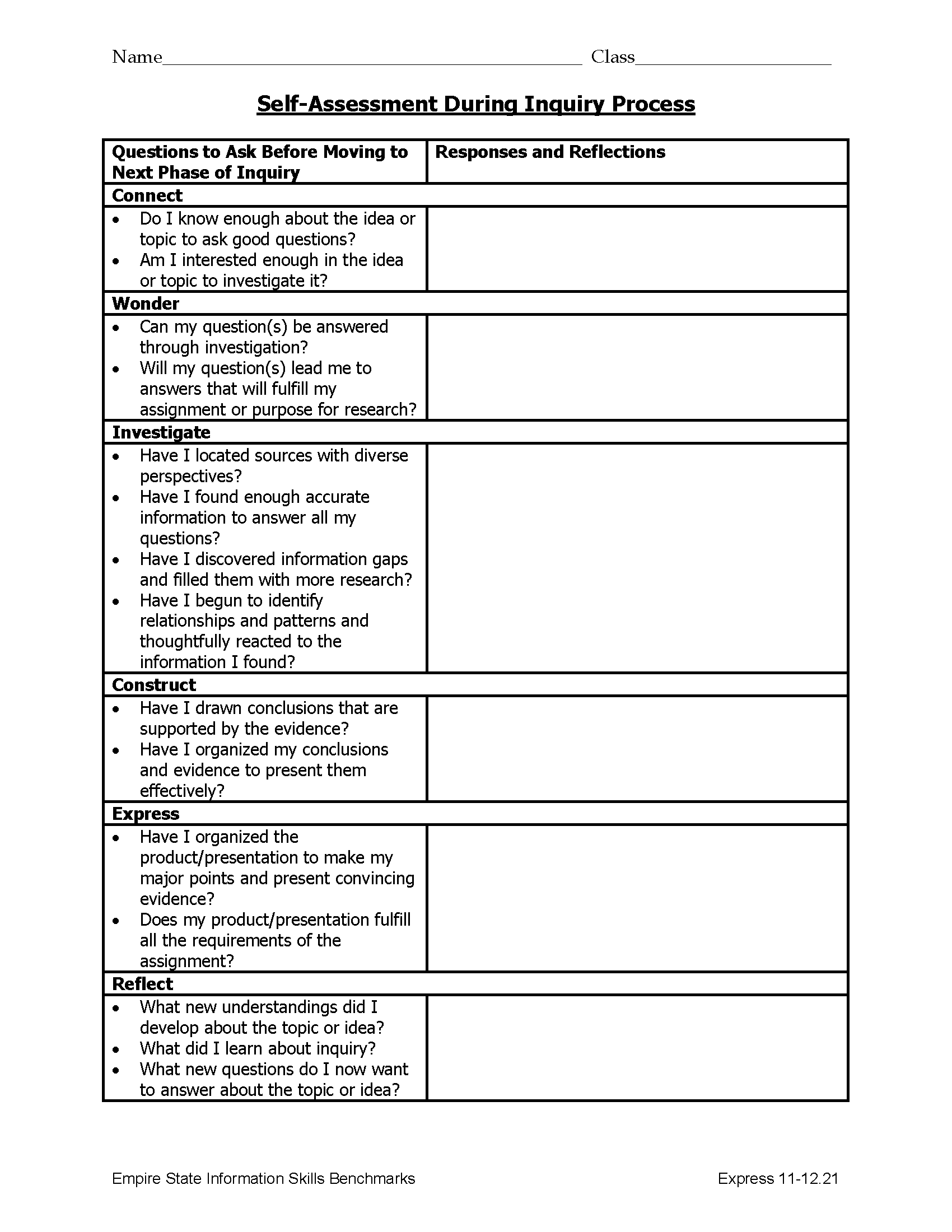

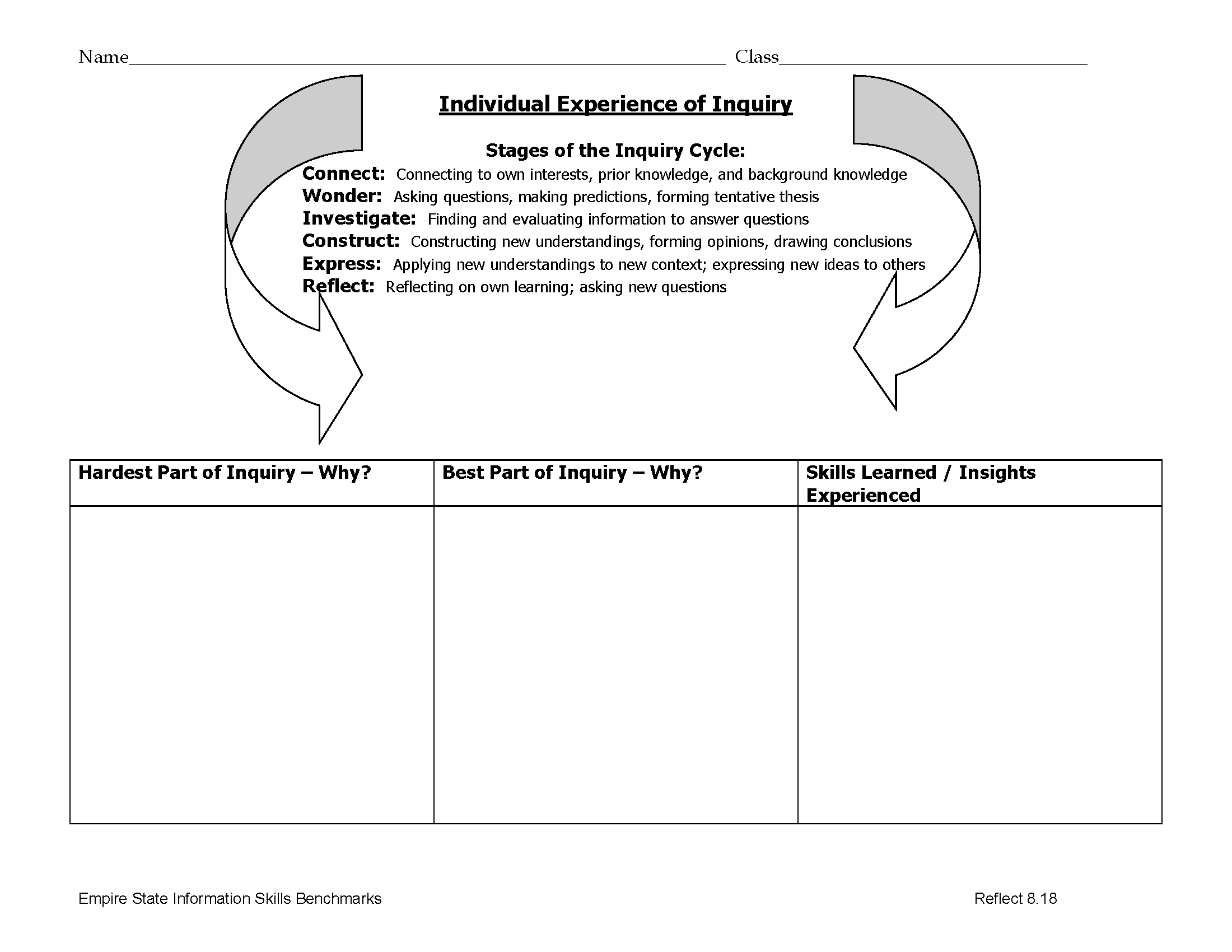

Reflect. Although reflection is built in to every phase of the inquiry process, the value in reflecting on the entire process and product at the conclusion of the inquiry experience is that it enables the learner to move from a look at one experience of inquiry to a broader perspective on inquiry as a process and a stance on learning. The concluding reflection allows the learner to self-assess and to be in charge of setting personal goals for improvement. The first template below offers questions for the learner to ask himself throughout the process of inquiry (11-12.21).

Students at every grade level can be asked to think about their individual experience of inquiry. The graphic organizer below can be adapted for any grade level (8.18).

Half of the fun of using graphic organizers in order to guide students during their independent practice is designing organizers that enable students to be transparent in their thinking while they are performing a skill. Librarians can use these formative assessments to discover when students are struggling and perhaps even where their confusions lie. Students have a sense of completion and success when they have been able to successfully follow the thinking process inherent in the deep reading and inquiry skills we are teaching.

14th March 2021 at 2:02 pm #38477Thank you for this thoughtful post, Barbara – the inclusion of exemplary graphic organizers is particularly helpful.

You use the term graphic organizer, rather than worksheet, very deliberately, and I think that I am beginning to understand the difference. I, for one, would be very grateful, though, for an explanation of the difference from your perspective.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.