Reading for Inquiry Learning

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Reading for Inquiry Learning

Tagged: reading

- This topic has 16 replies, 6 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 11 months ago by

Olga Nesi.

Olga Nesi.

-

AuthorPosts

-

15th March 2021 at 7:39 pm #38629

Graphic organizers (at least the ones I create and use) are different from worksheets in several important ways. First, graphic organizers are skill-based, not content-based. In other words, they are designed to guide students through the thinking process of performing a skill and to provide transparent evidence that they can perform the skill successfully. Students must think while they are working through a graphic organizer. They cannot copy their text on the organizer from any external resource; they cannot simply parrot information that someone else has already figured out. Traditional worksheets, on the other hand, often ask students to find the right, content-based “answers” in their resource or textbook and simply rewrite the answers on the worksheet.

Graphic organizers are used as a part of instruction, not as a replacement for instruction. They are used in the moment of an instructional lesson when students are ready to apply the skill on their own, after the skill has been taught, modeled, and practiced as a whole class. I think we have all had the experience of trying to learn a new skill (I think of learning new technology applications) by reading step-by-step instructions and then realizing that we haven’t really learned the skill until we try to do it. Well-designed graphic organizers provide the opportunity for students to practice the skill on their own; as an added bonus, they often offer embedded guidance and support to students through prompts, strategic visual design (e.g., Venn diagrams or mind mapping webs), reminders, and checklists. By using graphic organizers, students can independently practice applying a skill they have just been taught, but at the same time feel supported by the scaffolding built in to the organizer.

Graphic organizers are powerful tools to use for formative assessment of skill development. They allow teachers to see how well students have applied a new skill to build new knowledge and understanding. Well-designed graphic organizers will enable teachers to assess where and even why students are confused and respond either by intervening with individual students or by reteaching the skill to the whole class. In other words, graphic organizers are most useful during the process of learning so that adjustments can be made, rather than as a summative assessment to assign a grade at the end of a learning experience.

I think perhaps the main reason that I love using graphic organizers is that they allow me to see inside a learner’s mind. They allow me to join my learners on their path to new understandings. To me, graphic organizers are an effective tool for engaging with learners during a reflective inquiry journey.

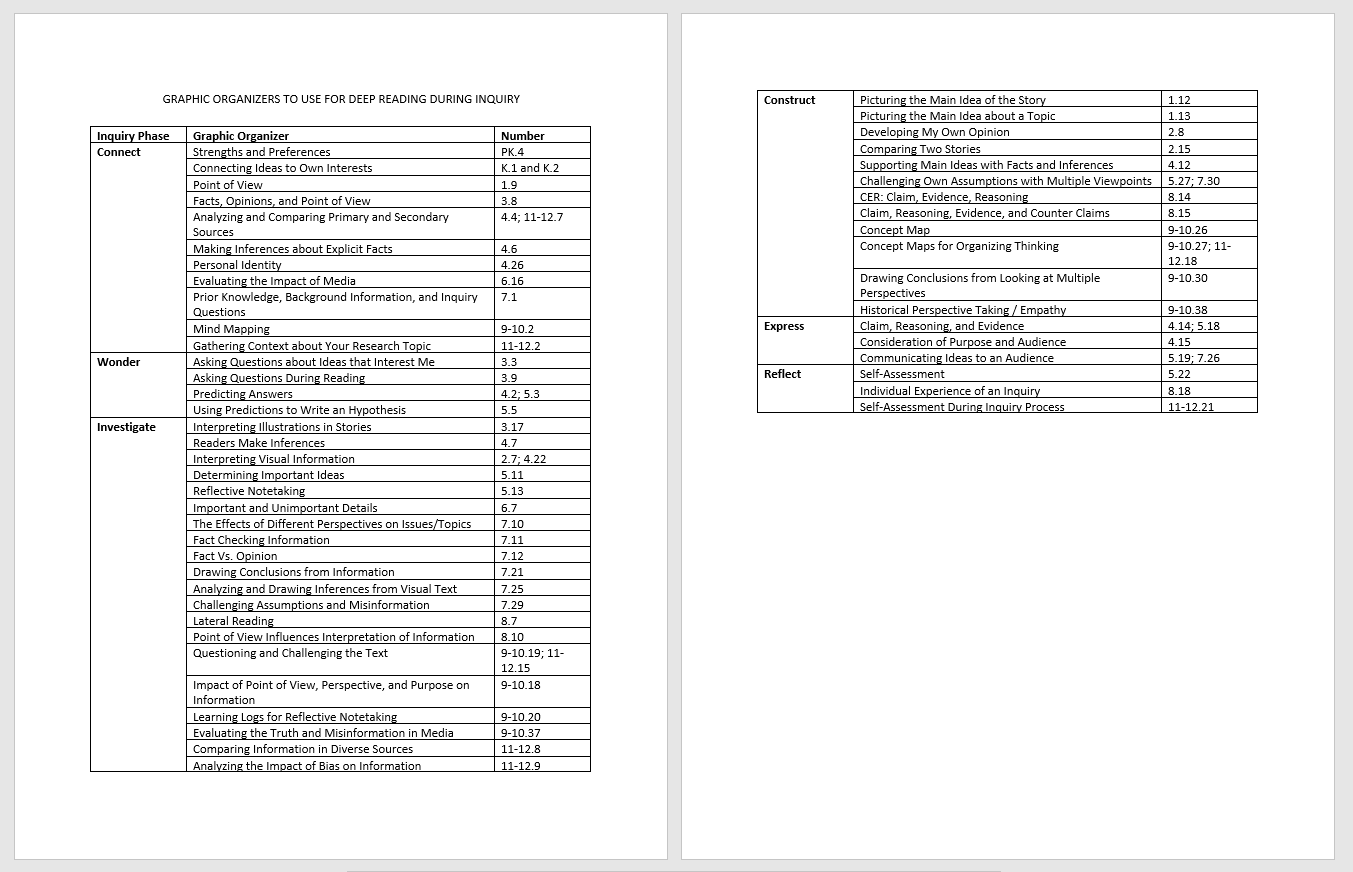

Here is a list of ESIFC graphic organizers that I think would be most appropriate for teaching the skills of deep reading (click on the image to expand it).

30th March 2021 at 12:38 pm #41797

30th March 2021 at 12:38 pm #41797Inquiry, Deep Reading and Questioning

Inquiry implies questioning. If we accept that questions are the drivers of any meaningful inquiry endeavor, then it stands to reason that questioning takes place throughout the process of creating new knowledge and continues well beyond the point of having cycled through the inquiry process iteratively. The issue for me has always been that while my students are extremely adept at “finding” answers to low level questions, they have largely been discouraged from asking the kinds of questions for which answers are not readily available. Therefore, when it comes to inquiry, deep reading and questioning, I would like to propose a paradigm shift from reading for answers to reading for questions. I propose this shift precisely because students already know how to find answers without reading deeply at all. Besides, I am not at all interested in teaching students how to find answers to questions that have long been answered.

Considering the world we live in and the problems confronting us, it is my belief that our students should be taught how to be unafraid to ask questions that have no immediately apparent answers and then they should be taught the process for making answers to those questions. After all, any and all substantial human achievement started with a question that did not have an answer. Then, via the process of inquiry, an answer was constructed. More pertinently: all of the content our students study was created by people working in their respective fields, asking un-answered questions and then creating (via inquiry) answers to those questions. “Learning” that focuses strictly on studying, memorizing and regurgitating the answers to other people’s questions, hardly encourages an inquiry stance. In point of fact, this kind of learning stifles the very idea that all new knowledge comes from questions that were at one time un-answered.

I first had this idea about reading for questions (versus reading for answers) when thinking about the following: What is the only question you can ask about something if you do not know anything about it? (“What is it?”) Additional questions can only be generated by reading – hence, reading for questions. It seems fair to say that the more questions a student can generate about something they have read, the more deeply they must have engaged with it. Then, it is not a far leap to assert that the value of any given piece of information we select for use with our students, should be based on its potential to spark questioning (versus basing the value of information on how many questions it answers). Incidentally, this is precisely why the pre-digested information in text books ranks lowest in value for teaching students how to read for questions. To say nothing of the notion that we might consider evaluating students not by how many “already answered” questions they can answer, but rather, by the quantity and quality of questions they are able to generate about something they have read.

Asking Questions at Each of the Phases of Inquiry

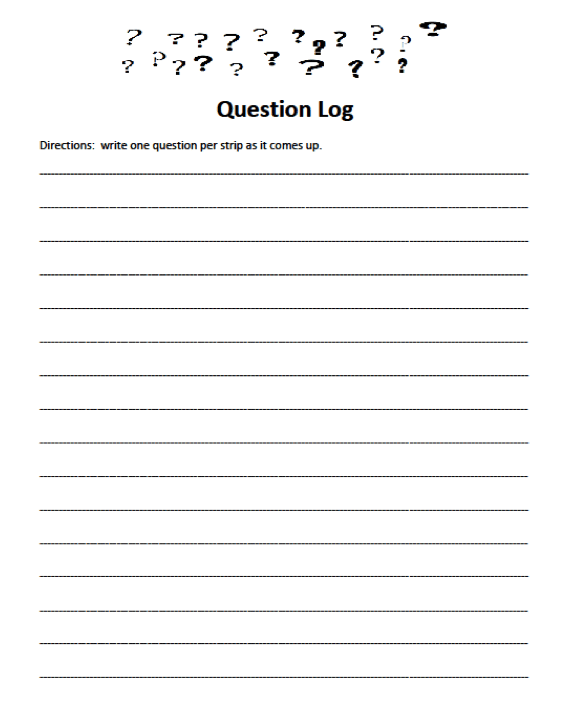

Ideally, students are encouraged to ask questions throughout an inquiry unit. This need not be an overly burdensome instructional activity. I encourage my students to use a Question Log to write down their questions as they come up.

As their question sheets fill up, the students cut the strips up and sort their questions into the various phases of inquiry. Of course, this presupposes that they have been taught about the phases at the beginning of the unit and that they have developed some understanding about the kinds of activities that take place in each phase.

Types of Questions Asked at Each of the Phases of Inquiry

Connect Phase

In this phase, students’ questions have primarily to do with the ways in which their topic relates specifically to them and what they might already know about it. I have found it to be useful to design activities that draw out of the students what they already know about a given topic and encourage them to make connections between what they already know and what they are getting ready to learn more about. For example, in an inquiry unit on the topic of Child Labor, I designed an assignment that asked my students to interview their parents and grandparents about the kinds of “work” they were expected to do when they were children. The students were then asked about the kind of work they do. Finally, they were asked to draw some conclusions about what they learned about how the work expectations had changed between the generations. (As most of my students’ parents and grandparents emigrated to the U.S. from China, the students were surprised to learn that older members of their families were expected to contribute in substantial ways to their households.)

Wonder Phase

As the students begin to explore their topic further, their questions tend to be “content” driven, meaning they have to do primarily and specifically with the topic they are exploring via reading a wide variety of materials in various types of formats. Thesis statements are developed in this phase, as well as guiding questions. These questions will go on to inform and direct their search for additional information in the next phase. Here, the students will have to analyze their guiding questions to determine if they “fit” with their thesis statement.

Investigate Phase

In the Investigate Phase, the students read for additional questions when they begin note-taking (see below for a lesson idea on note-taking for questions). Keeping well in mind that inquiry is an iterative process, the students toggle back and forth between investigating and asking additional Wonder questions. Wondering does not end at a pre-defined point – and hopefully, never. Additional questions in this phase have to do with evaluating the appropriateness of resources for use.

Construct Phase

In this phase, questions fall into one of several categories: organizational, evaluative and thesis supporting. For example: students will have to make decisions about how best to organize their information for ease of use and for the making of a cogent claim that is well supported by the best possible evidence. As such, they will also need to evaluate their information for completeness and for whether it supports or refutes their thesis.

Express Phase

Questions in the Express Phase pertain primarily to product creation and presentation types. Students consider the audience for their product and (hopefully) decide for themselves the best presentation format. Evaluative questions revolve around the creation of the best possible product for the intended audience, using the most suitable presentation type.

Reflect Phase

In this phase, students reflect on the effectiveness of their product and how well they did with the inquiry process. As such, the questions are evaluative of both their product and the process they went through to create it. Finally, students generate additional unanswered questions about their topic. What else do they want to know more about? The beauty of these “last” questions is that they suggest that inquiry is a continuous process. The more we learn, the more we want to know. The more we know, the more we know how much we don’t know, the more questions we have.

In the Library: Note-taking by Question

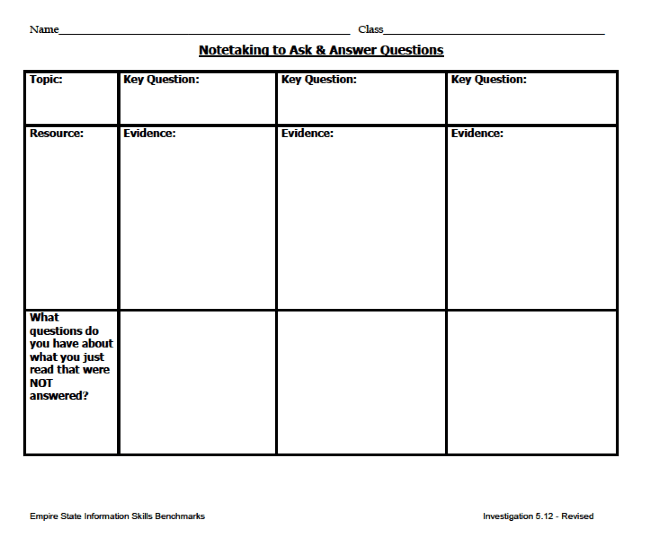

I have found that Note-taking by Question is a good way to get students to generate questions they are genuinely interested in answering. Thus, though note-taking falls under the Investigate Phase of inquiry, I have also found it to be a useful way to get students to engage more deeply with what they are reading by expecting them to generate questions on a given topic that are NOT answered by the reading and that they are curious about. I suppose this means I am using this graphic organizer as part Wonder, part Investigate. Details (and an example) follow below.

The specific strategy employed in this lesson is to ask my students to think about what question is answered by what they just read (vs. starting with a question and going on a superficial search for the answer). I start my note-taking lessons by asking the students if they are familiar with the game show Jeopardy. Most of them say that they are, however, when I ask them how it is played, they reply with some version of: “The host asks the contestants a question and they answer it.” It takes us a bit to get around to the way the game is actually played: the contestants are given categories and answers. They must provide the questions.

For this lesson, the students do much the same in the order following below:

- They read a paragraph

- They come up with the question that is answered by what they just read (admittedly, this is a sneaky way to get them to engage with the text more deeply)

- They write that question in the margin of the paragraph (this turns out to be the main idea of the paragraph)

- They re-read, underlining ONLY the information that answers the question (these turn out to be the supporting details – sometimes they discover extraneous details!)

- Finally, they come up with additional questions that the paragraph sparked that were NOT answered. These questions potentially become the focus of their personal inquiry.

We use a modified version of ESIFC graphic organizer 5.12.

The first time I did this lesson, I knew I was on to something. An eighth grade class was reading a selection on wolves. Following the introductory paragraph, the section header stated what the next section would be about: The Wolf Pack. Clearly, the question that was going to be answered by the reading was: What is a wolf pack? Indeed, the section went on in great detail defining and describing the wolf pack. Buried in an avalanche of information on the wolf pack, was one particular fact: the alpha male is the only male member of the pack that gets to mate and it gets to do so with all the female members of the pack. When I asked the class to tell me what question was answered by the section, one student raised his hand and said: “Why is the alpha male wolf the only one that gets to mate?” In point of fact, this question was not answered at all. The mating habits of the alpha male were merely stated as one fact (of many) that described the wolf pack. Thus, one student’s personal line of inquiry was born and I was given a perfect example of a question that was NOT answered by the text that a student was interested in pursuing on his own. And though, obviously, this particular question has long been answered, the student was on his way to understanding that his question was a valid line of inquiry and he was thrilled to have inadvertently modeled completing the bottom box on the graphic organizer.

Child Labor Tough Questions

Returning to the Child Labor unit I mentioned earlier, one student’s questions absolutely stunned me in their complexity. His thesis statement was: We contribute to child labor by purchasing products that are made (in part) by children. His guiding questions follow below:

- What products are created using child labor?

- What are the reasons that we keep buying these products?

- What happens when it is discovered that a company is using child labor to make a profit?

- What companies use child labor?

- What are some things we can do to lessen this problem?

This process of training our students to ask questions that do not have answers is a gradual one and starts with honoring their individual interests. As they acclimate to the idea that they are indeed entitled to their curiosity, their questions will get increasingly more difficult to answer. I would argue that these are precisely the questions we want them to be free to ask. I would also argue that the discomfort engendered by these questions and the difficulty of getting them answered is a testament to the importance of teaching our students to adopt an inquiry stance. They may never have answers to all their questions. They must nevertheless be encouraged to ask them. Inquiry, after all, begins, progresses and ends with questions.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.