Reflecting on E&L Memo 1 with Barbara Stripling

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Reflecting on E&L Memo 1 with Barbara Stripling

- This topic has 8 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 11 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

9th November 2020 at 5:25 pm #28213

I am delighted, Barbara, that we are able to take the time to unpack some of what you so generously shared with us in Epistemology & Learning Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry.

As I wrote in my introduction to your Memo:

Seymour Papert (1993) argued that the kind of knowledge children most need is knowledge that will help them get more knowledge. This epistemological concern – a concern with what knowledge is and how we get knowledge – is the starting point for our deliberations on how children learn to know, because what we think about learning, and therefore education (especially in schools), depends on what we think about knowledge.

The first thing that strikes me is that you became a librarian having been an English teacher. If you don’t mind me asking, when was that? I ask because it is my understanding that school library colleagues in the US are, by and large, specialist teachers, in that they are teachers who have specialised in school librarianship, which itself has areas of specialization. If so, this is the exact opposite of the situation in the UK, where very few school librarians are qualified teachers, and even those who are professionally qualified librarians will not have been able to specialize in school librarianship, even if they had wanted to.

What is interesting to me in this regard, is that neither your professional education/ training as a teacher nor your professional education/ training as a school librarian appears to have equipped you with the knowledge and/ or skills and/ or dispositions necessary to approach learning to know and understand through inquiry, which is an epistemological stance. Is this still the case (which it would be here), or was the transition to school librarianship perhaps not as quick as it seems? If so, how practically do teachers and librarians arrive at this epistemological stance?

—

Edit (10 November 2020)

I was reminded in this regard of the following from Daniel Callison’s The evolution of inquiry: controlled, guided, modeled, and free (2015, p. 39, emphasis added):

They [Barbara Stripling and Judy Pitts] tied the library to the classroom and demonstrated how the library could be a center for learning across the school. While a wide variety of learning activities was possible, the team did not incorporate inquiry learning as a model until they entered doctoral studies later in their respective careers. They were, however, early movers for involving teachers with media specialists as co-instructional designers. Stripling (2011) documented again in her dissertation that a school librarian’s effectiveness is diminished if librarians limit their role to that of resource provider, resulting in no integration into classroom instruction. … In both [their respective doctoral] studies, these two exceptional leaders in the school library instructional field found, from the vantage point of the researcher, with greater observation and analysis, that moving students as well as their teachers toward grasping the principles of inquiry was an extremely formidable task. School library media specialists are not likely to accomplish that task without a deep understanding of inquiry as well as being accepted fully into a co-instructional role. This implies extensive education in inquiry principles and application for those who seek a position as an educator in a twenty-first-century learning environment.

Might Callison have said that moving students as well as their teachers, including librarians, toward grasping the principles of inquiry was an extremely formidable task? If so, who is doing the moving?

—

Callison, D. (2015). The evolution of inquiry: controlled, guided, modeled, and free. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Papert, S. (1993). The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. New York: Basic Books.

12th November 2020 at 11:08 pm #28819Darryl,

I became certified to teach English and drama after finishing my undergraduate degree (majoring in Speech and Drama, minoring in English) and taking an additional year of graduate courses (mostly focused on educational theory and student teaching experiences). I learned teaching practices, but essentially nothing about the mental processes of learning. I taught middle school and high school English and drama for three years before I became a librarian. I did complete two Master’s degrees in those years – one focusing on Communications and Theatre and the other on Education: Instructional Resources (or school librarianship). With my second Master’s, I had courses on school library management, collection development, and youth literature, but limited coursework on teaching and learning.

To be honest, I never thought about the process of learning when I was an English teacher. I did try to get my students to think, but, as I said in my epistemology [see Epistemology & Learning Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry], I did most of the thinking and asked my students to react to my ideas. I started to explore how to teach students to think only after I became a librarian. Two things happened during my years as a high school librarian that led to my focus on a research process initially and then an inquiry process – I took additional graduate education courses to lead to an Educational Specialist degree and I pursued my own in-depth investigations about topics that interested me (like authentic assessment).

The learning that I did during those 16 years as a building-level librarian was powerful because I was able to translate the theory and research into my practice. I figured out a way to implement every educational theory that intrigued me. That’s why Judy Pitts and I developed a research process and a taxonomy of authentic research products. We collaborated with teachers to design instructional lessons and units that allowed us to try out our ideas, improve them, and build on them.

My shift to inquiry and an inquiry model did not occur until I became a library administrator and completed the thesis for my Ed Specialist degree. Inquiry was the focus of my thesis and I studied it in depth. From there, I developed the model that I have continued to explore and refine ever since as a library administrator, doctoral student, and library educator.

What I realize is that my preparation as a school librarian helped me to get a glimpse of my role as a teacher, but I did not actually understand teaching and learning through the library until I pursued learning on my own and had the opportunity to implement the ideas in my practice as a school librarian.

By the time I became a professor in a Master’s of Library Science program, I was convinced of the necessity for teaching school library students about inquiry, teaching for inquiry, collaboration with classroom teachers, and the literacy and inquiry skills that all students need to learn. I know that there is increasing emphasis in graduate programs for school librarians across the United States on teaching and learning, inquiry, and the librarian’s role in integrating process skills with classroom content through collaboration. I suspect that every school library graduate program takes a slightly different approach, emphasizing some aspects more than others. I do not see a strong push toward inquiry-based teaching and learning emanating from most graduate education/school library preparation programs.

As I admitted, I did not really learn about inquiry in my own graduate education. Rather than focusing on pre-service preparation of school librarians, I think we might be better served to focus on supporting continuous and collaborative in-service education. The role of professional organizations, national and international standards, and accessible professional development may be pivotal in bringing the profession of school librarianship to a new level of understanding and implementation of inquiry principles and practice. The conversations facilitated by the FOSIL Group are an example of the collaborative effort that will have an impact.

17th November 2020 at 9:51 am #29521Thank you, Barb.

This reminds me of John MacBeath’s observation that one of the most important lessons to come out of more than forty years of literature on school failure is that “teachers must recognize the limitations of teaching and become much more sophisticated in their understanding of learning”. MacBeath – Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge – made this observation in 1993, and one could argue that we have become much more sophisticated in our understanding of learning, and arguably we have. However, for this to make any actual difference to learning, one would also have to argue that we have become much more sophisticated in our teaching for learning, especially independence of learning through inquiry, which is arguable.

There are no doubt many and complex reasons that combine to make “moving students as well as their teachers toward grasping the principles of inquiry an extremely formidable task” (see first post above). While these need to be addressed, perhaps we first need to take step back and ask why the effort required for this extremely formidable task is both worthwhile and an urgent necessity. What is at stake if we don’t make the effort, or make the effort but do not succeed?

I happen to be reading Neil Postman’s The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School, in which he writes (pp. x-xi):

Without a transcendent and honorable purpose schooling must reach its finish, and the sooner we are done with it the better. With such a purpose, schooling becomes the central institution through which the young may find reasons for continuing to educate themselves.

Might these be connected?

—

MacBeath, J. (1993). Learning for Your Self: Supported Study in Strathclyde Schools. Strathclyde : Strathclyde Regional Council.

Postman, N. (1999). The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. New York: Vintage Books.

21st November 2020 at 6:57 pm #30462I do agree with Postman’s statement that “schooling becomes the central institution through which the young may find reasons for continuing to educate themselves,” but, as a librarian, I see two other important goals that schooling should accomplish. My first thought turns to the independent learning skills that young people need to develop and practice during their school years. Having reasons to continue learning beyond school is only half the battle, because our young people will not be able to realize their desire to educate themselves if they do not have the critical thinking, literacy, and inquiry skills they will need to do that. No one should graduate from school without the ability to ask good questions, find authoritative information to answer their questions, evaluate the credibility and accuracy of the information, seek and assess multiple perspectives, form their own opinions and draw conclusions based on evidence. The skills that librarians assume responsibility for teaching will not only prepare their students to educate themselves, but also to participate actively and ethically as members of society.

A second goal for schooling that goes beyond Postman’s vision is the acquisition of deep understanding about important concepts in the various realms of knowledge. To me, effective schooling is not the accumulation of information or even knowledge. I believe that students must transform knowledge to deep understanding by making it their own, learning to apply concepts to new situations or challenges, and presenting the expressions of understanding to the world. Actually, that’s why I am so committed to inquiry. The process of inquiry enables the learner to develop and express new understandings with self-confidence and personal voice. Inquiry experiences during school provide a foundation of understanding about the world and lead to the continuing quest for developing new understandings beyond the years of schooling.

Obviously, I take a much more positive view of the value of school than Neil Postman. But I recognize that most schools struggle to deliver the three-part value that I have outlined – reasons for continued self-education, the skills of independent learning, and deep understandings about the world. That’s a tall order of reform needed. Where do we start? Do we need a revolution or an evolution?

24th November 2020 at 3:41 pm #30950So, schooling may become the central institution through which the young may find reasons for continuing to educate themselves if it can be imbued with a transcendent and honourable purpose. Inquiry – understood as a dynamic process and stance of being open to wonder and puzzlement leading to knowledge and understanding of the world – broadly provides such a purpose, for, as Balzac declared, “the world belongs to me because I understand it”. However, this depends on students developing the skills that enable inquiry, and this over their time at school and within the context of subject/ content area learning.

A tall order indeed.

This brings to mind Thomas Kuhn’s The structure of scientific revolutions (1996), in which he describes how paradigms – “constellations of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community” (p. 175) – shift, or collapse, when they become overwhelmed by anomalies that they cannot accommodate/ account for. I guess for those who can read the signs, the paradigm shifts (reform), which is never comfortable, while for those who can’t read the signs, the paradigm eventually collapses (revolution), which is always traumatic.

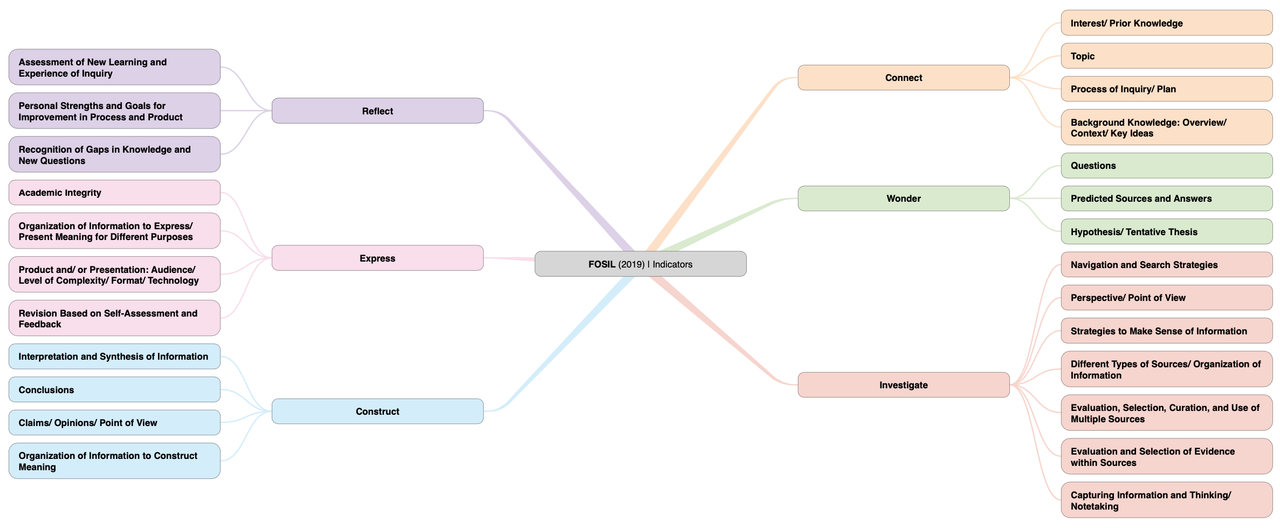

One of these anomalies is the widespread belief that it is either content or skills. You, following Dewey – experiences [that lead to “genuine education”] must include both “acquisition of the organized bodies of information” and “prepared forms of skill which comprehend the material of instruction” – are adamant that skills must be integrated into the teaching of content to enable learners to comprehend information and build knowledge. In fact, one of the considerations that drew me to your model of the inquiry process was the underlying framework/ continuum of skills that enables the inquiry process within subject/ content area learning. This, in my opinion, is a phenomenal undertaking and achievement, and one of the outstanding features of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum. With reference to the indicators (skill sets) below, might you shed some light on how this continuum was initially developed and has since evolved?

—

Kuhn, T. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

14th December 2020 at 11:45 pm #32700My understanding of the thinking skills underlying inquiry has evolved over the years. Because of my early emphasis on teaching research as a thinking process (as Judy Pitts and I explored in our book, Brainstorms and Blueprints) and my deep dive into critical thinking skills, I started to analyze each phase of the research process, and later the inquiry process, to determine the necessary thinking skills for each phase. When I moved my own focus from a somewhat linear research process to a recursive inquiry process, I intensified my efforts to delineate the skills required to successfully perform each phase of inquiry.

At the same time, I fleshed out my concept of inquiry so that I began equating “inquiry” with “learning.” That broader vision of inquiry led me to expand my understanding of the necessary skills to include literacy/reading comprehension skills and even those skills that are rarely taught in school – study skills like notetaking and identifying main ideas. As I worked on defining the skills over the years, I realized that the big categories that I started with (e.g., evaluating information) were actually composed of more specific skills (e.g., differentiating fact vs. opinion; determining point of view).

The third insight that evolved over the years was the need to develop a continuum of skills. Most of my years as a practicing school librarian were in a high school, so my early work on developing the curriculum of skills that I taught was focused solely on the high school years. I made decisions based on the types of thinking that every high school graduate should be able to demonstrate (based on my own experience as a teacher and librarian, the insights of my classroom-teacher collaborators, and national school restructuring initiatives). When I became a library administrator, I finally broadened my perspective enough to realize that skills needed to be taught and practiced over the entire educational experience, from early elementary through high school. And thus, the idea of a K-12 continuum of skills was born.

For the last half of my career, I have worked intensively to develop a robust PK-12 continuum of skills that I think should be taught or fostered by school librarians. As I reflect on that development process now, I can identify several strands that shaped my thinking and led to the comprehensive 2019 edition of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum. My development process was as recursive as the inquiry process itself, so it would be impossible to identify the order in which I tackled the issues inherent in the continuum.

Identification of the Essential Skills. My focus has remained on the thinking skills required by inquiry and learning, but I broadened my vision to include all of the major areas where school librarians have a responsibility. The standards of the ESIFC illustrate that broad view; they focus on inquiry, literacy, social responsibility, and independent reading/personal exploration. As technology and digital inquiry and literacy have become important, essential skills in those areas were also identified and integrated into the continuum.

The Stages in the Development of a Skill. Probably the most complex aspect of developing the continuum was figuring out the stages of developing a skill and matching those stages to the developmental abilities of young people. If, for example, the essential skill is the interpretation and synthesis of information, third graders should be expected to state the main idea with some supporting evidence; seventh graders should be able to interpret information and ideas by defining, classifying, inferring, resolving differences, and verifying evidence; and twelfth graders should be able to assess the strength of different perspectives by evaluating the supporting evidence for each. My process in figuring out the development of each essential skill was to cover my floor with large template matrices, spend weeks laying out and revising the sequence of skills inherent in the development of the identified essential skills, and then to check my thinking with librarians who teach at the different grade levels.

Technology Skills. Although I am aware that many librarians are called upon to teach basic technology skills, I included only the ones that applied to learning and communicating ideas. I, therefore, did not include keyboarding, but I did include navigating a website.

Social and Emotional Skills. In recent years, I have turned my attention to the development of the whole child, not just the intellectual capacity of the child. I included social and emotional skills that could (and should) be developed as students are conducting inquiry and pursuing their independent reading and personal learning. Pre-kindergartners can be taught to be self-aware by identifying their own feelings and sharing them with others when appropriate during story hour. Upper elementary students can be taught to identify and respect cultural differences and diverse opinions. Grade 7 students can be taught to empathize with literary characters, peers, people in the local and global community, and social issues by placing them in their historical or social context.

Social Responsibility Skills. In my opinion, school librarians should assume responsibility for teaching students the skills to participate actively and ethically in the world, both within and outside of the school. Certainly, in the age of burgeoning social media, our students need to be prepared to protect their own privacy, ensure that they are consuming credible and authoritative information, and build a positive online profile through their own participation in the online environment. The ESIFC incorporates these social responsibility skills at appropriate ages.

When I revised the ESIFC in 2019, I realized how much the information fluency skills needed by our students had changed since the original publication of the ESIFC in 2012. I am sure that those skills will continue to evolve as the information world changes. Dialogue among school librarians and teachers who are interested in ensuring that their students are information-fluent inquirers will help us refine and develop the continuum of skills that we teach. As we continue to deepen our understanding of inquiry-based learning, we will be able to identify emerging essential skills and prioritize what the students in each school need to learn. It’s an exciting journey and I am delighted to engage with FOSIL colleagues to evolve our thinking.

1st January 2021 at 12:06 pm #33500Jacques Ellul (1989) impressed upon me the view that history is the consequence of ideas, and this is how I read the unfolding history of school librarianship. One of the things that I most value about this opportunity to learn together is your deep insight into this history, which is insight gained from an active role in giving shape to it.

According to Daniel Callison (2015, 2006), the evolution towards inquiry in and through the school library can be traced back to 1960, and he asserts that the school library exists as a learning centre because of inquiry. In this regard, I find the following observations by Jesse Shera (1972, emphasis added) enlightening:

Increasingly, research as a method of instruction and an environment for formalized learning is being introduced into undergraduate as well as graduate programs. This undergraduate research, or more properly, inquiry, has its own characteristic information needs, though academic librarians generally have given these requirements slight attention, while the faculty has tended to ignore them almost entirely. This neglect may doubtless be attributed to the fact that the instructors themselves were not properly encouraged in the use of the library in their own undergraduate years. The textbook and the reserve collection, which in the final analysis is only a kind of multiple text, have too long dominated undergraduate, and even graduate, instruction. The teacher’s own mimeographed reading lists and bibliographies have been imposed between the student and the total library collection, largely because the typical faculty member does not trust either the bibliographic mechanisms of the library or the competence of the librarians, while the librarians, for their part, have never developed a theory of the role of the library in the student’s intellectual experience. This neglect has been intensified by the absence of any real communication between teacher and librarian, both have paid lip service to the library as a “learning center,” and having said that satisfied their sense of obligation with a short course or a few lectures on “How to Use the Library.”

There is much of interest here, but of immediate concern is research, or more properly inquiry, as a method of instruction and an environment for formalized learning that has its own characteristic information needs, which, it seems to me, forms the basis of a theory of the role of the school library in the student’s intellectual experience. This theory is encapsulated in the idea of the library as a learning centre because of inquiry – meaning both that inquiry gives birth to and sustains the library as a learning centre and the library as learning centre gives birth to and sustains inquiry – which demands more of us and our classroom colleagues than lip service.

This evolution towards inquiry is reflected in the 1st (2002) and 2nd (2015) editions of the IFLA School Library Guidelines, with a shift in pedagogical focus from information literacy – which is itself a shift from discrete information skills (1970s) to information skills embedded in an information-seeking process (1980s) – to an inquiry process that embeds media and information literacy skills, amongst others. More broadly, Callison (2015) makes the point that information literacy, media literacy, critical thinking, and creative thinking were all concepts enveloped within inquiry since the mid 1980s.

As I mentioned above, your insight into this evolution towards inquiry is gained from an active role in giving shape to it:

- REACTS Taxonomy [of thoughtful research] in Brainstorms and Blueprints: Teaching Library Research as a Thinking Process (Stripling & Pitts, 1988)

- Stripling’s Model of Inquiry (2003), which FOSIL (2011) is based on

- New York City Information Fluency Continuum (2009)

- Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (2012)

- Reimagined Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (2019)

From this perspective, what value does each stage in this ongoing evolution from discrete information skills through information skills embedded in a research process to inquiry as a skills-enabled process and stance add to the intellectual experience of our students, who, as the IFLA School Library Guidelines forcefully remind us, we serve?

—

Edit (3 January 2021): Added link to REACTS Taxonomy (see below for overview).

—

Bibliography

- Callison, D., & Preddy, L. (2006). The Blue Book on Information Age Inquiry, Instruction and Literacy. Westport: Libraries Unlimited.

- Callison, D. (2015). The Evolution of Inquiry: Controlled, Guided, Modeled, and Free. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

- Ellul, J. (1989). The Presence of the Kingdom. Colorado Springs: Helmers & Howard.

- Shera, Jesse. (1972). Foundations of Education for Librarianship. New York: Wiley-Becker and Hayes.

- Stripling, B. K., & Pitts, J. M. (1988). Brainstorm and Blueprints: Teaching Library Research as a Thinking Process. Englewood: Libraries Unlimited.

10th January 2021 at 5:05 am #33986You asked about what each phase of the inquiry cycle adds to the intellectual experience of our students. I would like to add my thoughts about what having an inquiry stance and moving through each phase of the inquiry cycle adds to the cognitive, social, and emotional lives of our students. Those aspects are, of course, integral to the intellectual experience, because we know that we don’t set emotions and the social context aside any time we are learning, whether in school or in the world outside of school. Thinking about the social and emotional value of learning through inquiry is a fairly new and very intriguing area of what I’m thinking about these days.

We’ve had a tough week in the United States with the pandemic racing through the country and political unrest permeating our thoughts. I have my own thoughts about why our social context has become so fractured, but I thought I would try to look at it from a young person’s eyes (as much as I can imagine what they are thinking and feeling). I think both the pandemic and political chaos have threatened the values that make our students strong: safety, a sense of belonging, being listened to, finding meaning that connects with their lives, a sense of empowerment. I think many of our students feel scared, helpless, confused, and powerless. The question for me is: How can students develop positive emotional and social attributes while engaged in inquiry? Here are my first thoughts about how students can nurture their whole selves during the process of inquiry?

Connect. During this beginning phase of inquiry, students need time and opportunity to figure out who they are. What are their interests? What do they feel about the topics under discussion? What do they already know? Is what they already know correct? What personal experiences have they had in the past that are relevant? What do they want to know? What does the main topic have to do with their own lives? What do their classmates think and feel about the topic? This phase is a time of exploration, not only of the topic, but also of themselves. Students need to find personal meaning and motivation at this stage. They need to feel that they can be successful and safe in seeking to learn something new.

Wonder. Elementary-age children, especially early elementary, love to ask questions. They sizzle with curiosity. By the time they get to upper elementary and middle school, many have overridden their sense of wondering with the safe feeling they get when they stay within the guardrails of the teacher and established curriculum. But the essence of inquiry is the personal sense of wonder fostered in each individual. To help students develop the confidence to ask questions that matter to them and that stretch the boundaries of the prescribed curriculum, librarians and teachers need to provide a strong safety net and caring guidance, so that students know they can ask questions that are meaningful to them and also know they will have the time and opportunity to change those questions when they discover better ones. By focusing on the value of the inquiry process itself rather than on a final, “perfect” product, librarians and classroom teachers can help students feel empowered and safe in taking risks, failing, and asking deep and complex questions that they care about but that are difficult (or maybe impossible) to answer.

Investigate. So many cognitive skills are involved in the Investigate phase of inquiry that it is easy for librarians and classroom teachers to overlook the importance of the social and emotional skills necessary for students to move successfully through their investigations. Students may start by being confused about their focus, then frustrated because they cannot find the information they are seeking, then overwhelmed because they have found too much. Many students compensate by being laser-focused and ignoring the messiness inherent in inquiry, especially at this phase. Perhaps the timeline of the assignment has forced them to just get the job done. That transformation of inquiry into simple information-gathering means that students are not getting full value from the experience. It is incumbent upon the educators to infuse this phase of inquiry with teaching strategies and opportunities for students to get support from each other, to resist confirmation bias and persevere to seek multiple perspectives, to make sense of and form their own meaning from the information, and to get beyond their own assumptions and biases to develop empathy.

Construct. Construct may be the scariest aspect of inquiry for many students who have always learned what they were expected to learn from lectures and textbooks, but never have had to come up with their own ideas, opinions, or conclusions. I actually did not learn to do that until I was in college. If our goal is to imbue our students with self-confidence in their own expertise, then we must teach students to build their own understanding based on the evidence they have discovered. Certainly a great deal of scaffolding, support from educators and peers, and reflective conversations are necessary for students to feel safe, empowered, and confident to form their own interpretations.

Express. Although certainly the Express phase is about completing and communicating the final product, the real value of Express is in the personal attributes that students develop. When students are enabled (through scaffolding, guidance, and practice) to successfully present their ideas to others, they develop their own voice, self-confidence, and agency. They feel empowered to tackle another learning experience in the future. They adjust their own identity and begin to see themselves as experts.

Reflect. Reflection is an essential attribute throughout inquiry, but at the end of an inquiry experience, it adds an element of mindfulness that will position students for future learning. During this phase, students are asked to think about their own experience of inquiry as well as their final product. Sometimes students have been asked to keep a research log throughout the process to record their thoughts and feelings, which certainly makes this final reflection more authentic. Even if students have not tracked their own emotional and social growth during the process, librarians and classroom teachers can ask guiding questions that will enable them to parse their own emotional and social growth. That self-awareness will lead to more successful learning experiences in the future and a greater sense of satisfaction about what they have accomplished.

Of course, there are many other aspects of the student experience during inquiry that we should explore. I am interested in how we can know if students are getting the value we intend for them to gain through inquiry. I wonder how we can help students make inquiry a natural part of their lives, not just a stance that applies to their academic lives. I also wonder how students can maintain the healthy social and emotional attributes that we help them develop when they confront the real world of pandemics and political uncertainty. How do librarians and teachers empower all students to develop self-confidence, voice, and agency?

17th March 2021 at 11:49 am #39049I have moved the unfolding conversation about deep reading within the stages of the inquiry learning process to a dedicated Topic – Reading for Inquiry Learning – specifically this post onward.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.