Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning

Home › Forums › Inquiry and resource design › Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning

- This topic has 7 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 9 months ago by

Barbara Stripling.

Barbara Stripling.

-

AuthorPosts

-

19th April 2021 at 11:01 am #46904

Barbara and I are delighted to share our thinking ahead of our workshop at Real-World Learning Live!, “a four-day digital event that connects The Day‘s user community and some of the educators and thinkers that inspire us”.

The presentation is freely available here.

This serves two purposes. Firstly, as Barbara often says, writing is thinking, and thinking aloud in this way may be of benefit to others. Secondly, given the practical limitations of a 30-minute workshop, it will provide a useful point of further reference for interested delegates.

From Real-World Learning Live!:

“The Day provides schools with classroom-ready news stories and related activities. The Day builds cultural capital by explaining the news and linking it to the UK and IB curriculums. It is designed to support literacy (with multiple reading levels), oracy (through topical discussion topics), critical thinking, news literacy and a positive mental attitude with a range of activities from short lesson starters to full-scale debates. Above all, The Day helps nurture the global citizens of the future by giving pupils an insight into other people’s experiences and dilemmas around the world.”

We describe our workshop in the following way:

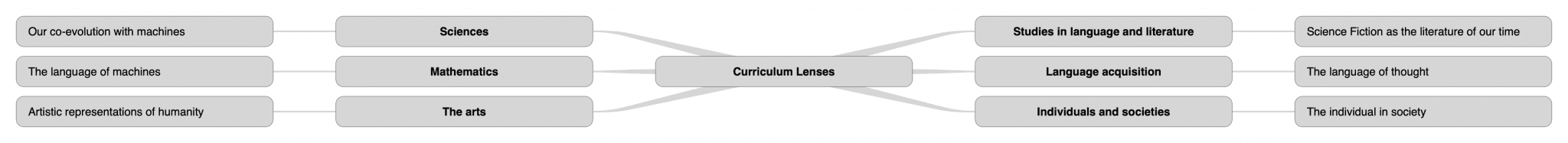

Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning

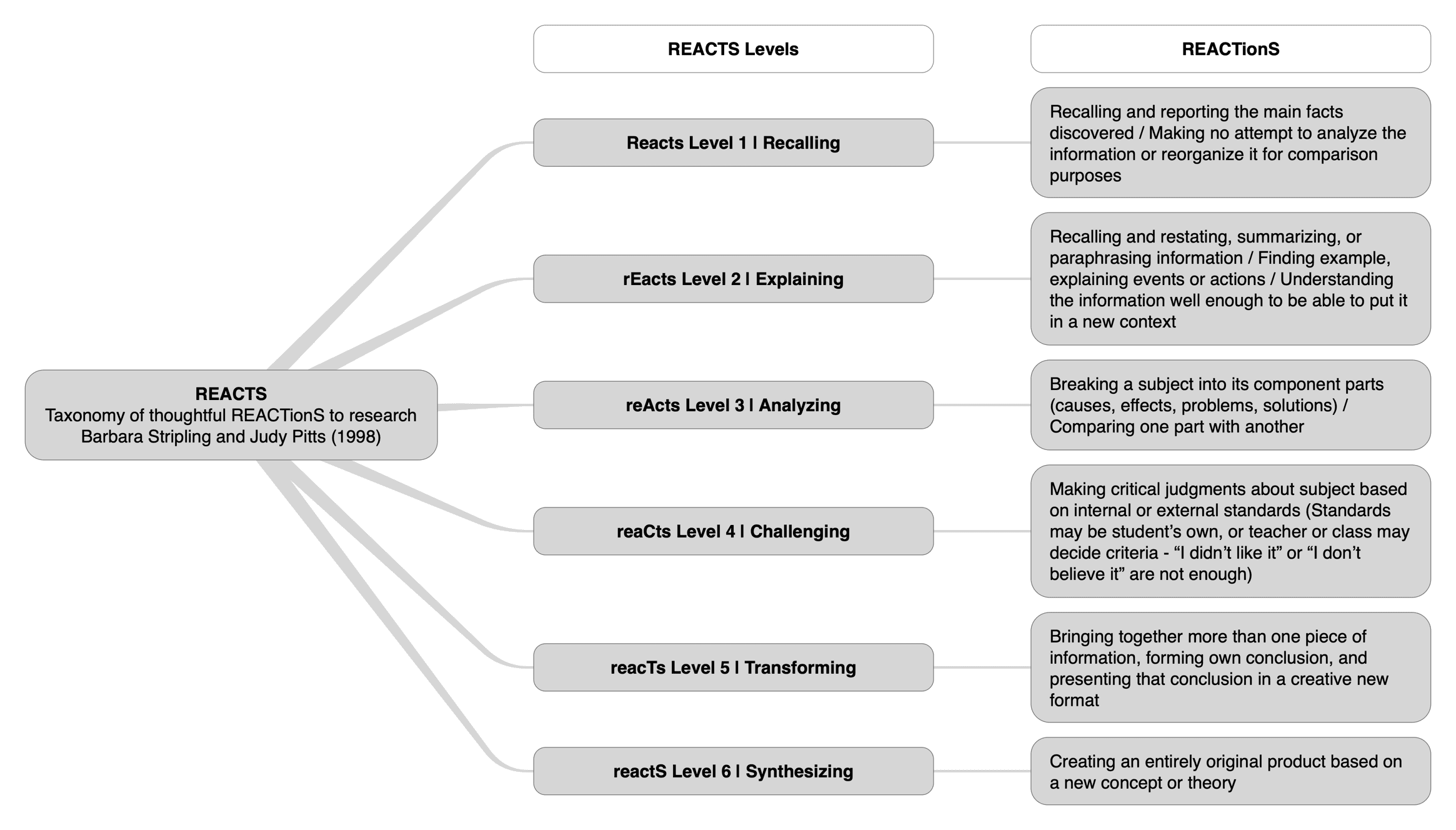

The widely influential Brainstorms and blueprints : teaching library research as a thinking process by Barbara Stripling and Judy Pitts, published in 1988, introduced their Taxonomy of Thoughtful Research (p. 3) and REACTS Taxonomy of Thoughtful Reactions to Research (pp. 9-10). The crucial insight of Brainstorms and blueprints is that if classroom- and library-based teachers “accept the importance of students’ thinking during research, [which students do not automatically do], then they must also accept the responsibility for teaching thinking skills” (p. 19). This, in turn, requires a “thinking frame for research, which is the research process” (p. 19). This treatment of the research process, in turn, laid the foundation for the development of Barbara’s highly influential model of the inquiry process (2003) and underlying framework of inquiry learning skills (2009, 2019), which FOSIL is based on.

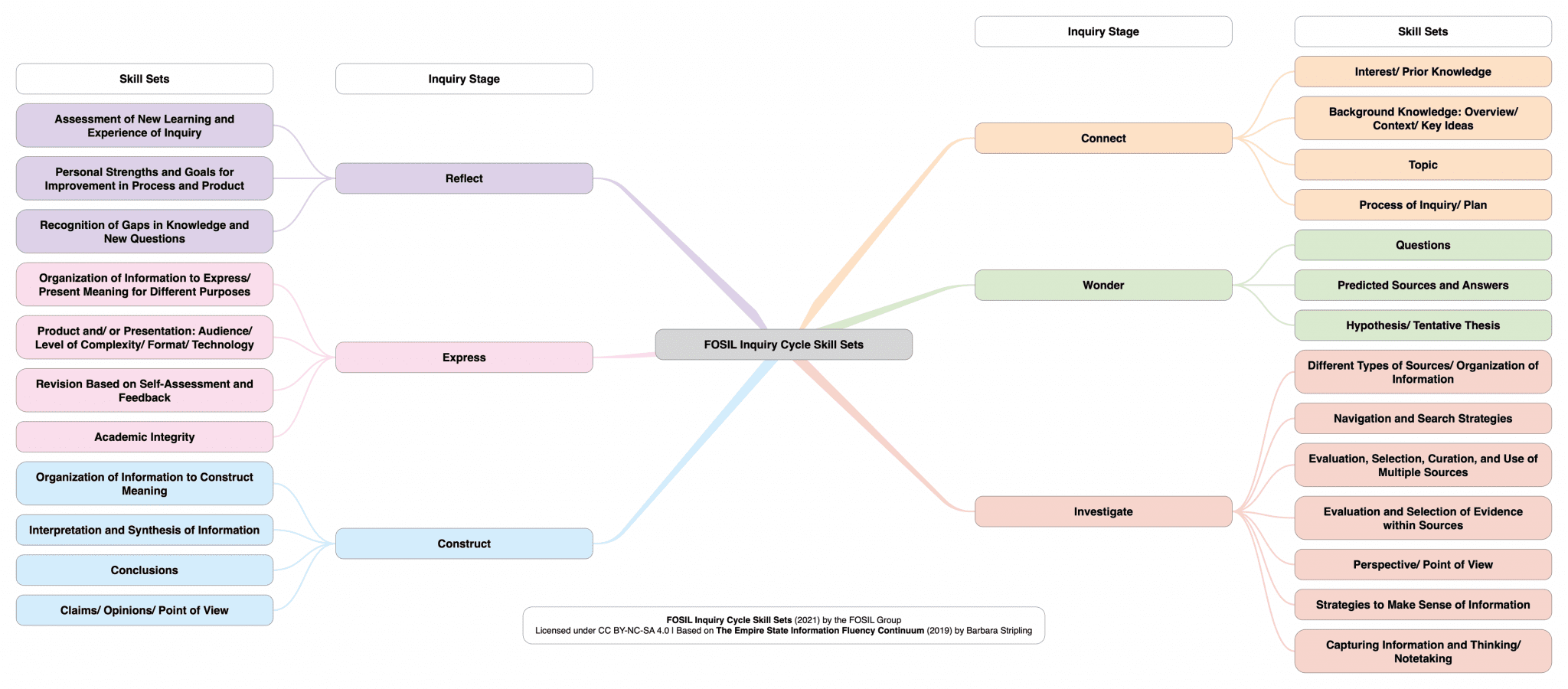

From the perspective of FOSIL, which stands for Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning, articles from The Day always lent themselves to thoughtful inquiry, being “news to open minds” presented in a thought-provoking way – the most highly-developed example of this being the Year 7 English Inquiry – Science Fictional Writing in the FOSIL Group Forums.

Some months ago Darryl was invited by Richard Addis to reflect on how the new format of The Day articles lent itself to a more inquiry-based approach to learning across the curriculum. This period of reflection, and discussion with Barbara, produced two insights. The first, and more obvious, insight was that the Six steps to discovery reflected stages in the inquiry process – in our case FOSIL. The second insight, which grew out of the first, was that the Six steps to discovery, if formulated carefully, could, in the process of a well-designed inquiry, also serve to step students through the six levels of the REACTS Taxonomy, but this would depend on circumstances.

This workshop will consist of two parts. Firstly, Darryl will share reflections on the new format of The Day articles as they relate to the inquiry process and the REACTS Taxonomies. Then, Barbara will imagine two very different teaching scenarios based around The Day, one in which severe time constraints limit inquiry to the article under discussion, and one in which more generous time constraints extend inquiry well beyond the article under discussion.

19th April 2021 at 12:35 pm #46924More specifically, I intend to cover the following:

- Inquiry as a process and a stance

- Overview of FOSIL and Stripling Model of Inquiry

- Relation of FOSIL to Six steps to discovery

- Overview of REACTS Taxonomy and how to use

- Importance of collaboration between librarians and classroom teachers to blend an inquiry stance with curriculum content

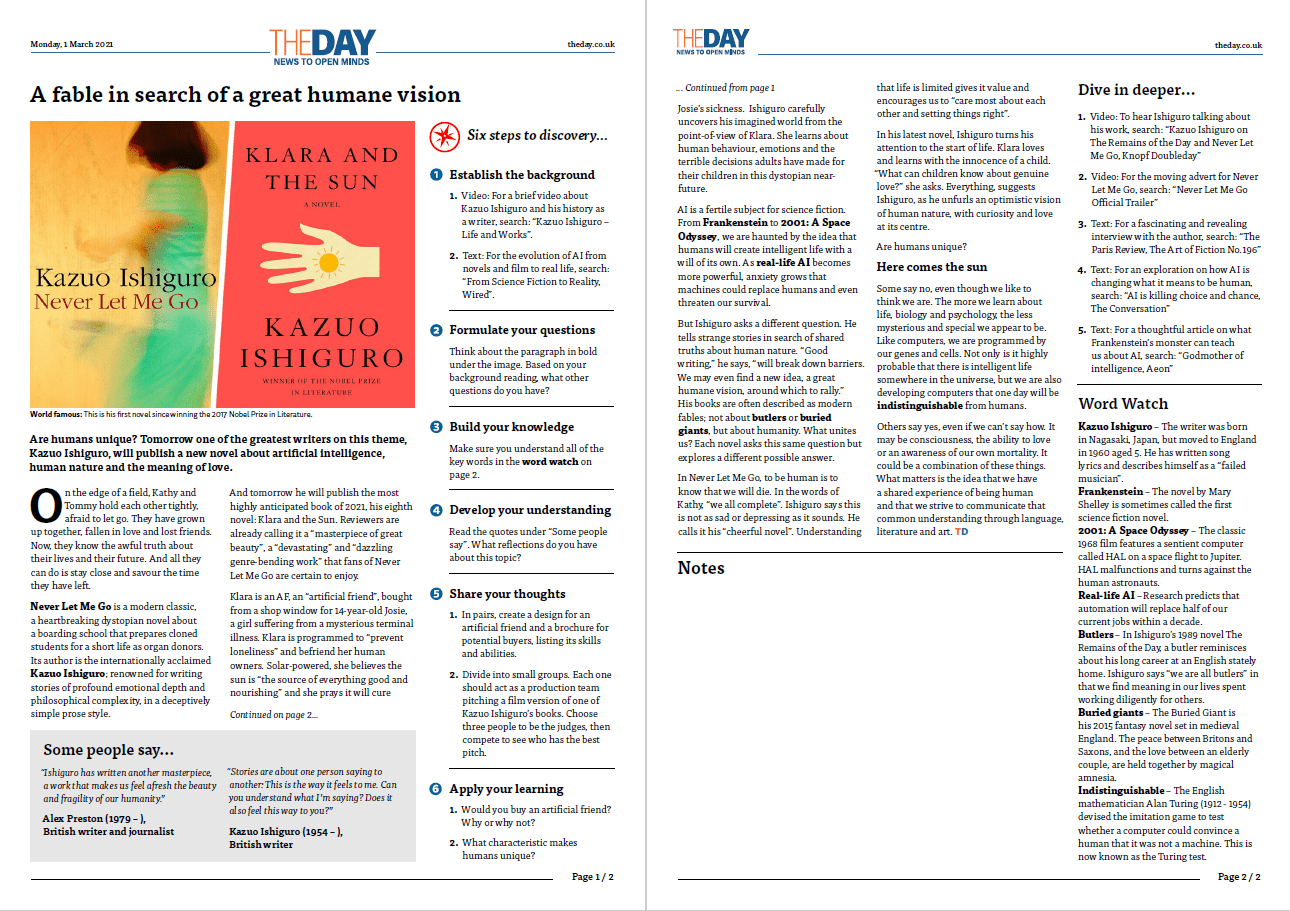

The article that we will be basing our workshop around is A fable in search of a great humane vision (see below for excerpt in old format).

Barbara will discuss use of the article in two teaching scenarios – one in which severe time constraints limit inquiry to the article under discussion, and one in which more generous time constraints extend inquiry well beyond the article under discussion. This discussion will include:

- Multi-disciplinary examples (English, Science, Technology, Social Studies, Arts)

- Suggestions for inquiry skills that might be taught in both scenarios

- Student products at different REACTS levels

It is essential to establish a conceptual frame at the beginning of a learning experience in order to focus on the core ideas that will drive the instructional design. An inquiry frame introduces the major concept(s) to the students and, at the same time, opens the possibilities for student-driven inquiry guided by that frame or lens.

Barbara will elaborate on this.

19th April 2021 at 10:08 pm #47022As Darryl and I started thinking about our presentation for The Day, we both realized immediately that many of the articles could be used to provoke deep thinking and inquiry across the curriculum. We also agreed that educators must frame and guide the learning experience to lift students beyond simple comprehension of the information in an article. A conceptual frame at the beginning of a learning experience will focus on the core ideas that will drive the instructional design. An inquiry frame introduces the major concept(s) to the students and, at the same time, opens the possibilities for student-driven inquiry guided by that frame or lens.

For me, a valuable frame that leads to inquiry is an essential question. I have always found essential questions somewhat difficult to write, because they force me to think deeply about the big ideas or concepts that underlie a specific topic. As an educator, essential questions make me a little uncomfortable, because I know that my students will never find the definitive answer (because there isn’t one). I value essential questions, however, because they provide direction, boundaries, and inspiration for inquiry investigations. They make me, as a continuous learner, excited to explore new ideas.

Darryl and I developed two essential questions that we could use to frame a learning experience with The Day article, “A Fable in Search of a Great Humane Vision.” I would choose one or the other, depending on the class in which I intended to use the article.

- What does it mean to be human?

- How might today’s actions and inventions predict the near and long-term future of humanity?

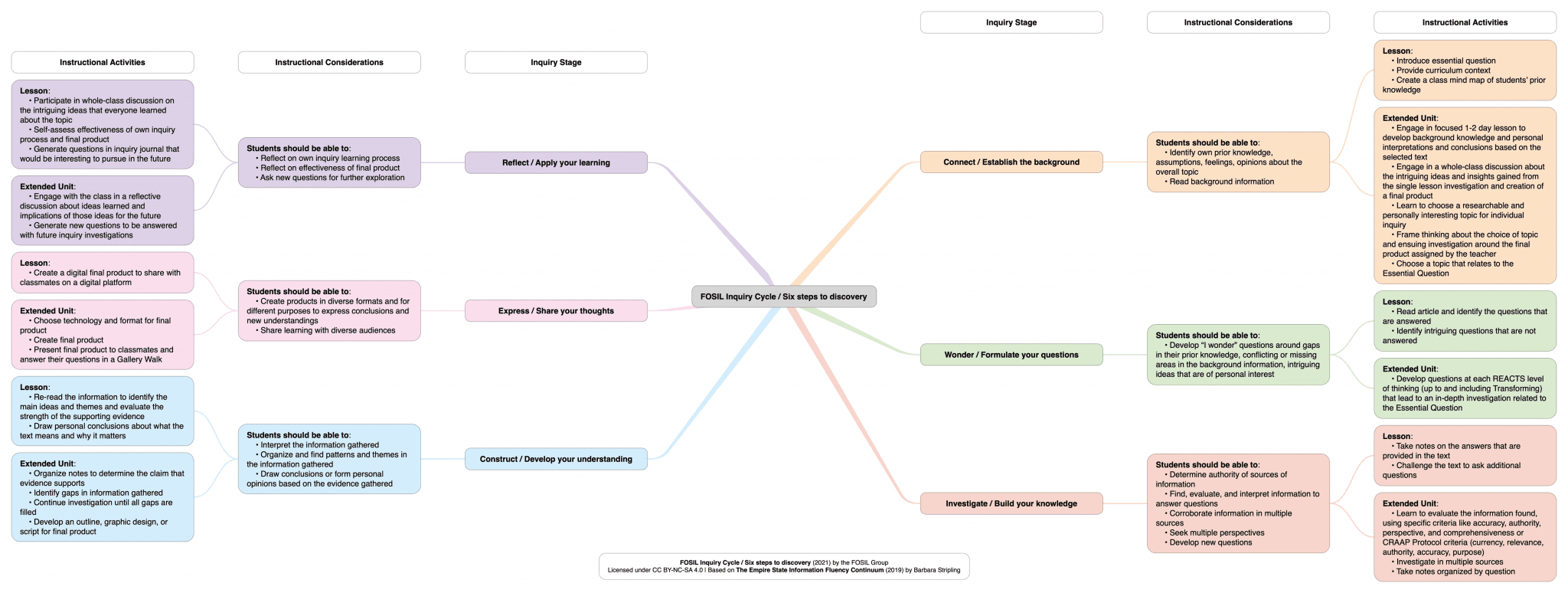

A second piece of framing that ensures that students focus on the content that is most important for specific curriculum objectives is defining a curriculum lens. From my perspective as a librarian with some insight into all curricular areas of a school, I identified possible curriculum lenses that could be used by educators across the curriculum. The classroom teacher and I, as librarian, would engage in a conversation to define the essential question and specific lens to frame our instructional design.

I developed a list of the possible curricular lenses.

Curriculum Area — Possible Lenses

English

- The synergy of science, humanity, and imagination in science fiction

- Science fiction conceptual themes:

- Humanity

- Community

- Power

- Progress

- Conflict

- The literary genre of science fiction

- Role of science fiction authors in world building

- Role of science fiction in mapping the future

Science – Biology

- Human development

- Genetics, cloning

- Free will vs. determinism

- Artificial intelligence

- Humans vs. animals

- Interplay between biology and psychology

Technology

- Dimensions of artificial intelligence

- Philosophical, ethical, religious implications

- Relation to humanness

- Intersection between humans and machines

- Impact of embedded coding

- Technological advances – who decides?

Social Studies

- Psychology concepts

- Social and emotional needs/competencies

- Relationships (e.g., friendships)

- Dispositions (e.g., empathy)

- Acceptance of status quo vs. choice to resist

- Sociology concepts

- Individual vs. group

- Social networking

- Community: what unites us, what divides us; inequality

- Civil unrest, protest

Arts

- Artistic expressions of humanity

- Painting and drawing

- Poetry

- Music

- Media

Darryl and I found the article in The Day so replete with possibilities for deep thinking, even in a limited, one- or two-day learning experience, that we had to restrain ourselves from continuing to add other ideas. We reminded ourselves to stay within the realm of the essential questions.

After deciding on an essential question and determining a curricular frame, educators are prepared to take the next step to design the instructional experience. Darryl is going to share our instructional designs for a limited experience (1-2 days) and an extended inquiry experience (8 days).

20th April 2021 at 3:31 pm #47253I am reminded by these two essential questions of Francis Fukuyama’s preface to Our posthuman future : consequences of the biotechnology revolution (2003), in which he revisits his argument that “Hegel had been right in saying that history had ended in 1806, since there had been no essential political progress beyond the principles of the French Revolution [which signalled] a broader convergence toward liberal democracy around the globe” (pp. xi-xii). This convergence toward liberal democracy, he argued, was tied to human nature, and he goes on to explore the greatest challenge to this end-of-history thesis, which is the very real potential of biotechnology to fundamentally alter human nature. Given this near-total collapse of the boundary between non-fiction and science fiction, the power of these essential questions becomes clear: on some level human nature gives rise to technological invention, which, in turn, calls into increasingly literal question what it means to be human in nature.

As Barbara touches on, once you adopt an inquiry stance of wonder and puzzlement on the world, essential questions serve the dual purpose of focusing the inquiry [lest we get too carried away] and energizing it [carrying us away].

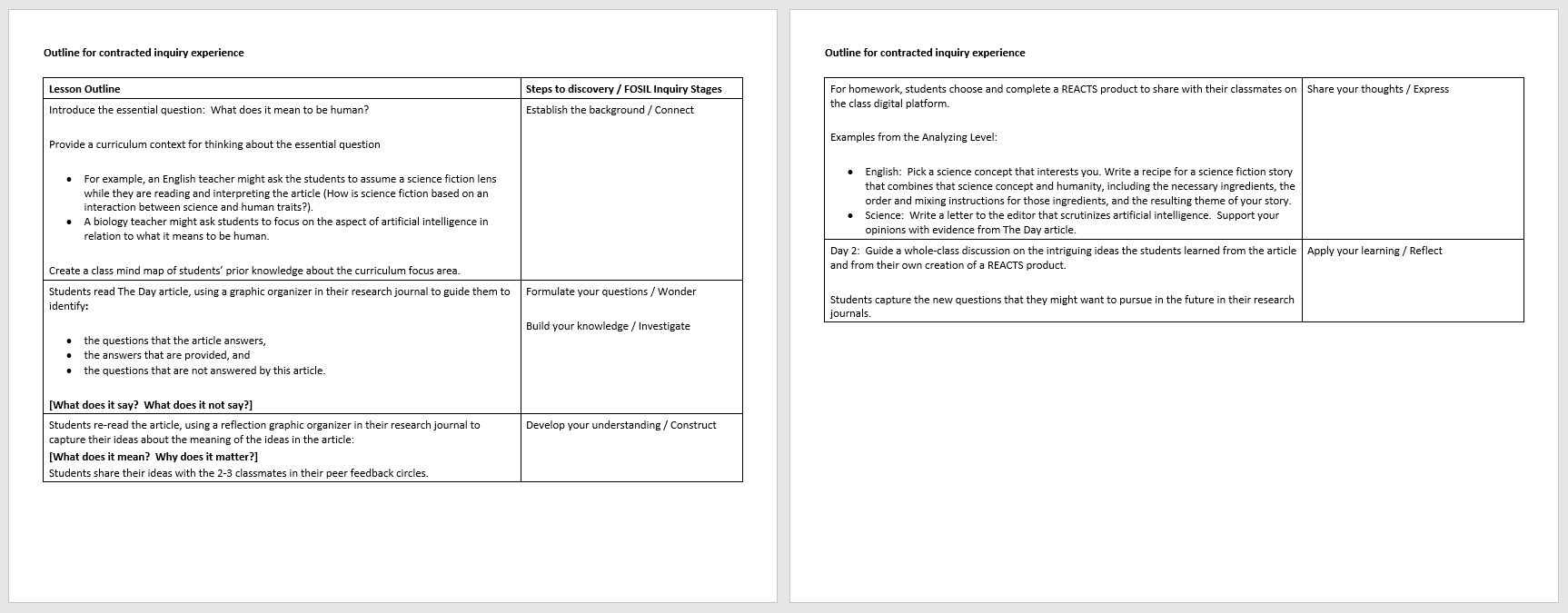

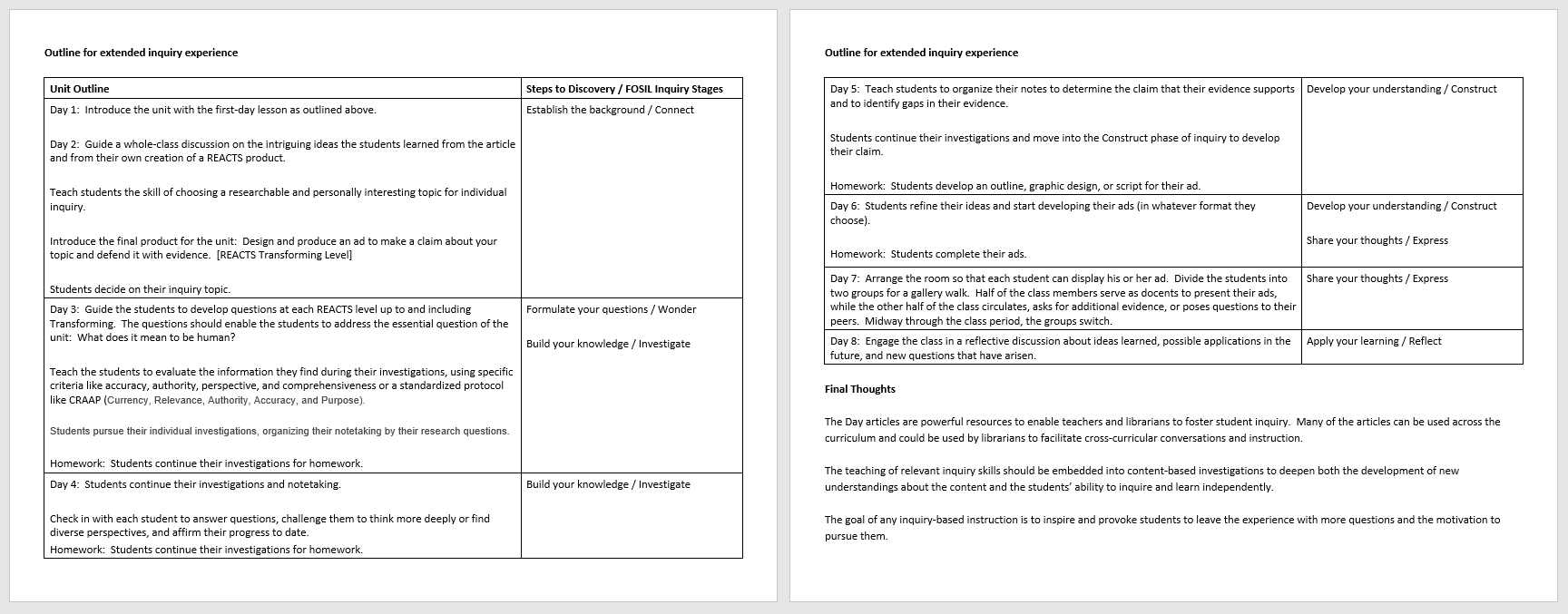

Our instructional designs for a contracted and extended inquiry experience follow:

Lesson outline (click image to expand):

Unit outline (click image to expand):

References

Fukuyama, F. (2003). Our posthuman future : consequences of the biotechnology revolution. London: Profile Books.

28th April 2021 at 1:54 pm #49395For the purposes of the workshop, I adapted the lesson and extended unit outlines above (click to enlarge or download as high-resolution PNG):

The lesson and extended unit outlines need to be approached through curriculum lenses, which for the selected article are (click to enlarge or download as high-resolution PNG):

We are very pleased to be previewing the new format of The Day, and discuss some of the instructional design features (click to enlarge or download as high-resolution PNG):

Finally, a discussion of possible application of the REACTS Taxonomy to an inquiry-based lesson or series of lessons (click to enlarge or download as high-resolution PNG):

28th April 2021 at 3:13 pm #49417

28th April 2021 at 3:13 pm #49417The workshop also touches on the inquiry learning skill sets that undergird the inquiry process, which I include here for convenience (click to enlarge or download as high-resolution PNG):

The skills that make up these skill sets may be downloaded from here.

3rd May 2021 at 12:01 pm #50972Following our presentation – Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning, which may be downloaded from here – at Real-World Learning Live!, we have two further opportunities for thoughtful reactions to The Day.

Firstly, Richard Addis, Founder and Editor of The Day, has asked us the following questions for a LinkedIn article:

- What is inquiry-based learning?

- Why is it so important?

- What is the FOSIL Group’s theory on how we develop young people’s thinking skills?

- What is your view on how we teach young people to think more critically about world issues?

- How can teachers apply inquiry-based learning when using The Day in the classroom?

Barbara has drafted our answers and will post them in due course.

Secondly, I have drafted the following questions to put to Richard for a FOSIL Group Forum post:

—

Question 1

Our working definition of inquiry is a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community.

This dynamic process of making sense of the world from information about the world is a learning process.

The IFLA School Library Guidelines frame learning through inquiry and advocate for the effective development of media and information literacy (MIL) skills within a chosen model of the inquiry learning process.

Question: How would you define news in relation media?

—

Question 2

The Day is both “news to open minds” and explanation of the news.

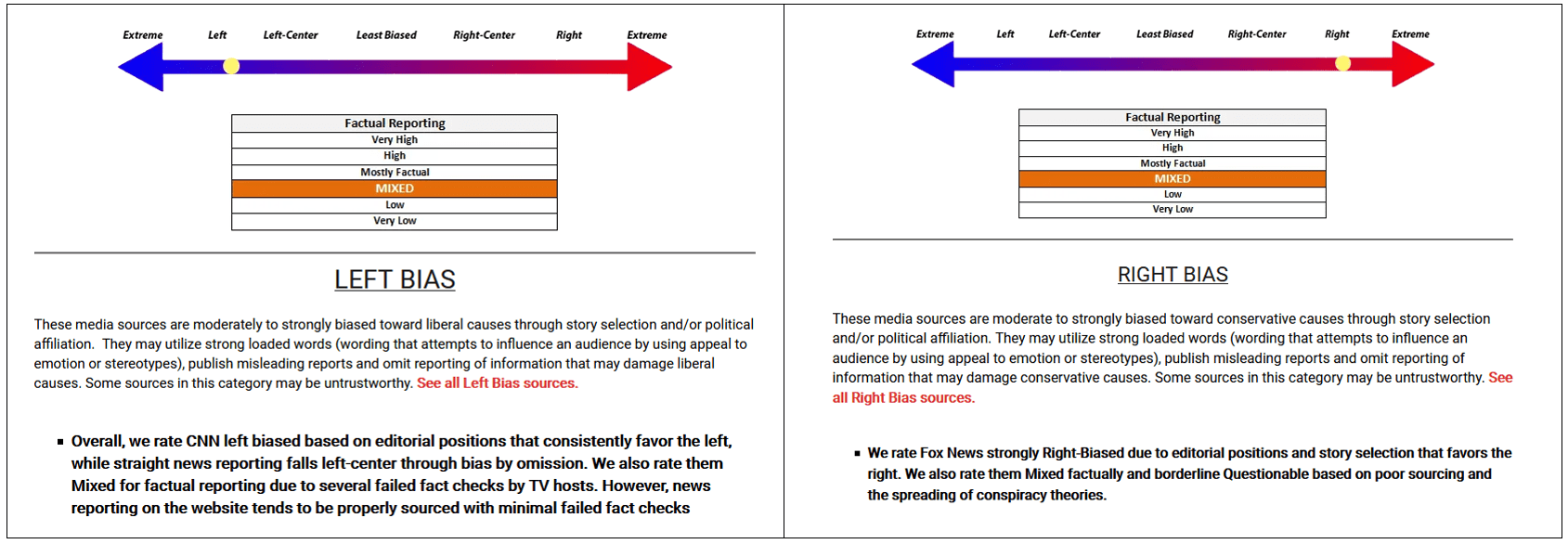

More broadly, this creates an apparent tension between factuality of reporting and commentary, in that commentary heightens awareness of editorial point of view, bias, propaganda, etc. An interesting example of this is CNN’s Brianna Keilar claiming that Fox is not news no matter what it calls itself, which, according to Media Bias/Fact Check (which itself is by no means infallible), might be a case of the pot calling the kettle black.

CNN according to Media Bias/Fact Check and Fox News according to Media Bias/Fact Check

Question: How does The Day manage this apparent tension?

—

Question 3

More specifically, there is an apparent tension between telling children what to think and provoking/ encouraging/ developing independent thought. This likely accounts for recent instructional design decisions relating to the format of The Day that make the inquiry learning process visually explicit, and so encourage an inquiry-based pedagogical approach.

Question: What was the motivation for these instructional design changes, and what are the desired outcomes, which may be subtly different?

3rd May 2021 at 4:32 pm #51023I have drafted some responses to the questions posed to us by The Day. It’s amazing how powerful it is to have a conversation among colleagues who bring different perspectives to it. I tend to assume that everyone defines concepts and terms the same way that I do. When someone asks me to clarify what I am thinking, it helps me think more deeply about my own assumptions.

Questions from The Day

What is inquiry-based learning?

Inquiry-based learning is grounded in centuries of educational theory and practice as well as in international documents. The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) has issued IFLA School Library Guidelines (2nd revised edition, June 2015. Editors Barbara Schultz-Jones and Dianne Oberg) and they offer an overview of inquiry-based learning and its major concepts:

Instructional models for inquiry-based learning generally use a process approach in order to provide students with a learning process that is transferable across content areas as well as from the academic environment to real life. These models share several underlying concepts:

- Student constructs meaning from information.

- Student creates a quality product through a process approach.

- Student learns how to work independently (self-directed) and as a member of a group.

- Student uses information and information technology responsibly and ethically.

The Galileo Educational Network (GEN) has been the professional learning arm of the School of Education at the University of Calgary for 22 years. GEN’s first principle is “Stewarding the intellect through inquiry-based learning.” GEN offers a definition of inquiry:

Inquiry is a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world. As such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created. Inquiry is based on the belief that understanding is constructed in the process of people working and conversing together as they pose and solve the problems, make discoveries and rigorously testing the discoveries that arise in the course of shared activity.

Darryl Toerien and I have enlarged the GEN definition to develop the following working definition:

Inquiry is a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis of responsible participation in community (Stripling and Toerien, 2021).

Why is it so important?

The goal of any educational system is to enable students to become independent learners for life. Young people who pursue an inquiry stance have learned the skills, attitudes, and questioning mindset to negotiate the complexities of their academic and personal lives. They have the self-confidence to make their own decisions, draw their own conclusions, and pursue their own futures. They recognize their responsibility to participate actively and ethically as members and contributors to their communities.

Inquiry is especially important in today’s fast-paced, information-glut society when every individual must sort through volumes of misinformation, disinformation, bias, gaps, and information lacking authority, accuracy, and reliability. The questioning lenses and attitudes of inquiry will enable students to challenge what they read, see, and hear and develop new ideas and understandings that are valid and accurate.

What’s FOSIL Group’s theory on how we develop young people’s thinking skills?

We develop young people’s thinking skills by 1) validating their sense of wonder and questioning; 2) explicitly teaching them the thinking skills of inquiry and providing many opportunities for guided practice; 3) integrating the teaching and use of thinking skills into knowledge-acquisition experiences, so that students are not just receiving information delivered by others, but they are developing their own understandings based on challenging and interpreting what they read or hear; and 4) teaching students to be mindful of their own thinking process, so that their self-reflections lead to further development of their thinking skills.

What’s your view on how we teach young people to think more critically about world issues?

Certainly, an essential piece of teaching students to think more critically about world issues is to teach them the critical thinking skills embedded in the inquiry process. We must also enable students to develop a critical stance on the world, confident to question why, so what, what else, and what if any time they encounter a new or intriguing idea.

Along with attention to students’ thinking skills, we must frame their encounters with world issues to focus on the underlying themes and concepts and to help them make connections to their own lives. Student could read about famine in a specific area of the world, for example, but they may not do more than accumulate a few facts unless they strive to understand the essential problem or question (e.g., the underlying causes of famine; the relationship between famine and climate, government, or other factors) and they connect as fellow humans to those who are experiencing famine.

How can teachers apply inquiry-based learning when using The Day in the classroom?

The Day – for those whose budgets allow for it – is an amazing resource for librarians and content-area teachers, both for its intriguing articles and for its application to inquiry-based learning. Because of the framing of articles by essential questions and extension resources and activities, the articles inspire focus questions in multiple content areas. The same article could be used by teachers of science, math, language, and social studies to probe ideas in those content areas inspired by the article. Examples of those curriculum connections for one article, “A Fable in Search of a Great Humane Vision,” are in the FOSIL Group Forum discussion, Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning (https://bit.ly/3ujkzu7).

Articles in The Day can be used effectively for one-lesson inquiry investigations and as opening provocations for larger inquiry units. In both cases, the teaching or scaffolding of appropriate inquiry skills is embedded as a way for students to develop deep understanding of the content and start drawing their own conclusions about the essential questions (as applied to the teacher’s curriculum focus). Examples of a lesson and a unit around the “Fable” article have also been posted to the FOSIL Forum discussion, Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning (https://bit.ly/3ujkzu7).

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.