Year 7 Science Project FOSILised

Home › Forums › FOSIL Presentations › Year 7 Science Project FOSILised

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 4 years, 10 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

25th April 2021 at 1:52 pm #58043

Although not a conventional presentation, FOSIL Group member Elizabeth Hutchinson , with assistance from Jenny Toerien and Darryl Toerien, has written an article – Year 7 Science Project FOSILised – for Teaching Times, published on 25 April 2021, which is included here in full.

—

Year 7 Science Project FOSILised

By Elizabeth Hutchinson, Jenny Toerien and Darryl Toerien

Following on from my previous article The Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning (FOSIL) can transform students’ knowledge of their subject I included a quote from Lance and Maniotes (2020) which stated:

Young people need guidance as they navigate a complicated media environment, and many teachers are themselves unsure how to help students locate credible information that will allow them to answer the questions they want to pursue. Their best option is to look to the school librarian for partnership and assistance.

This collaboration process is hugely important to inquiry learning and I will endeavour to demonstrate how the relationship between teacher and school librarian can have a big impact on work within the classroom. But first I want to address the notion that the only way to teach is through direct instruction.

This is a difficult conversation as our schools are judged by test results and one of the tried and tested ways to get our students through this process is to give them the information they need and then help them to give it back to us through an exam. I can understand how this has happened but want to demonstrate that direct instruction can and should be part of the inquiry learning process and can also positively impact exam results.

Inquiry learning is not an approach where the teacher offers no assistance and the students are expected to find out by themselves. As Tytler states, “direct teaching seems sensible for teaching facts, for instance, or for introducing and practicing skills, but what of higher-level outcomes where knowledge involves significant conceptual shifts?” This can come about from teaching through inquiry learning and within it teaching facts and practical skills too. Students taught this way show “high levels of student engagement and representational competence … through doing rather than learning about their subjects” (Tytler, 2019). Before going on to discuss how this all works, it is important to bear Tytler’s conclusion in mind:

Direct teaching advocates the gradual ceding of control to students after they have been taught techniques, and monitoring of their work, rather than our staged process of exploration, invention, evaluation and revision. The payoff, we argue, is that students come to know the disciplinary ideas in richer ways. We have found, however, that the approach requires of teachers both significant knowledge of the science and mathematics, and command of a pedagogy involving negotiation and refinement of student ideas, compared to ‘telling’. It also takes more time. However, if we are serious about developing STEM skills for interdisciplinary problem solving, we argue there are no shortcuts.

Year 7 Science Project FOSILised

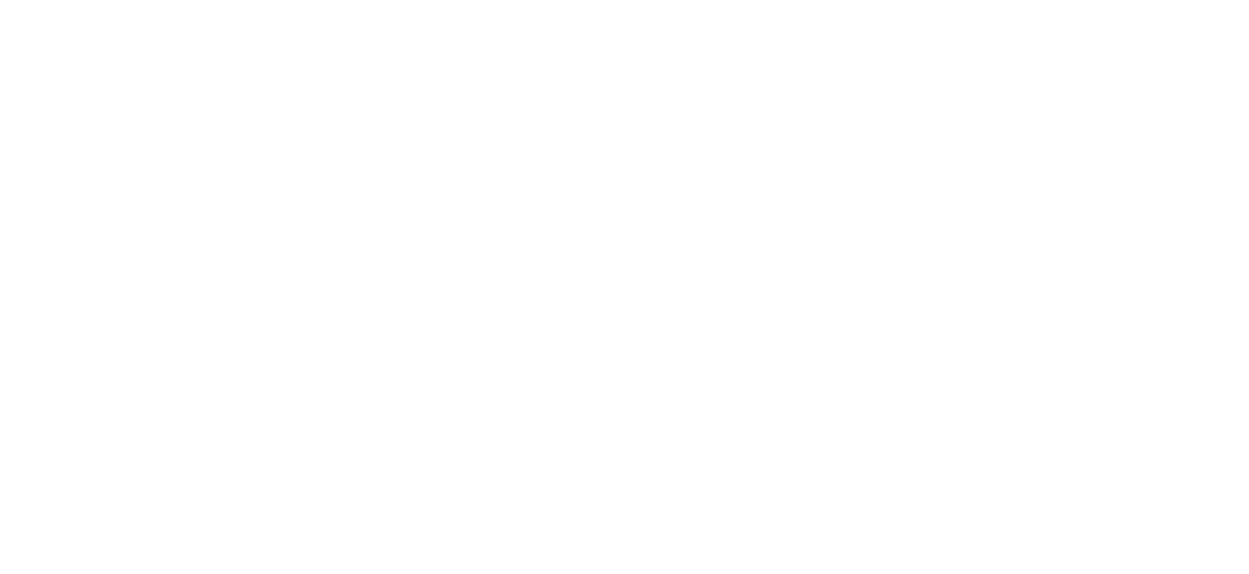

Chris Foster, Teacher of Chemistry and Head of Student Research at Oakham School, had experience of inquiry learning using a framework called FOSIL (Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning – see below), which I described in my previous article, in the Upper School (Years 12 and 13), but wanted to introduce it into the Lower School (Years 6 to 8) Science curriculum.

Knowing that FOSIL works most effectively in collaboration with the school librarian due to their expertise in the inquiry learning process, he discussed his idea with Jenny Toerien, one of the Curriculum Librarian’s at Oakham School, and they decided, rather than starting with a blank canvas, to focus on the work towards the CREST award that had already been running within the curriculum for a fair number of years with their year 7’s.

CREST is a UK student-led award in the STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths) that recognises success, and enables students to build their skills and demonstrate personal achievement in project work. It “inspires young people to think and behave like scientists and engineers” (2018). The CREST award is split into Star, SuperStar, Discovery, Bronze, Silver and Gold awards depending on the age of your students and can be run independently or in groups for a small charge per student. The idea is for the students to address a real-world STEM problem to develop collaborative, hands-on investigative skills for which, after being assessed by a teacher, they receive a personalised certificate.

It is important to note that CREST, in its approach to learning through real-world STEM problems, is an example of Project-Based Learning (PBL), which is “an inquiry-based instructional approach that reflects a learner-centred environment and concentrates on learners’ application of disciplinary concepts, tools, experiences, and technologies to research the answers to questions and solve real-world problems” (Krajcik and Blumenfeld 2006; Markham, Larmer, and Ravitz 2003). Consequently, FOSIL, which is a robust model of the inquiry learning process, is ideal for framing PBL.

Previously, Year 7 had been set a task to design a container to transport a water snake. The design brief was to keep the temperature of water in their container between 60-80 degrees Celsius for 20 minutes. As part of the project, pupils built and tested their snake container in small groups, completed a CREST booklet and gave a presentation about their artefact. Chris had noticed that “although pupils enjoyed the process of carrying out a project, they often failed to make links between the theory they had learned in class to the design of their snake carrier”. The new inquiry was much broader, allowing them to investigate design and build anything they were interested in that reduced heat transfer as part of its job.

Many students, when given an opportunity to run an experiment, want to head straight into the action with very little thought given to previous learning. The collaboration between Chris and Jenny led to them decide that the students needed help to link their previous work on mechanisms of heat transfer to their experimental design and they did this through creating an inquiry journal based around the FOSIL process helping them connect their learning to their design. To bridge the gap, they worked with their students immediately prior to the CREST project and included graphic organisers with worked examples in the materials to act as prompts for teachers to show pupils how theory and practice can be linked and then invited pupils to complete similar graphic organisers for other methods of heat transfer.

The inquiry journal for the CREST project based around Heating and Cooling is made up of several graphic organisers, created to guide students through the inquiry process, thereby serving an instructional purpose, whilst also acting as an assessment tool to ensure that students are understanding the process and building their knowledge and understanding. This first graphic organiser initiates the CONNECT stage of the FOSIL Cycle. This is where students are asked to engage themselves in the inquiry through recognising and understanding what they already know, and maybe what they don’t. As these students have already learnt about heat transfer it is a good opportunity to remind and guide them back to that learning.

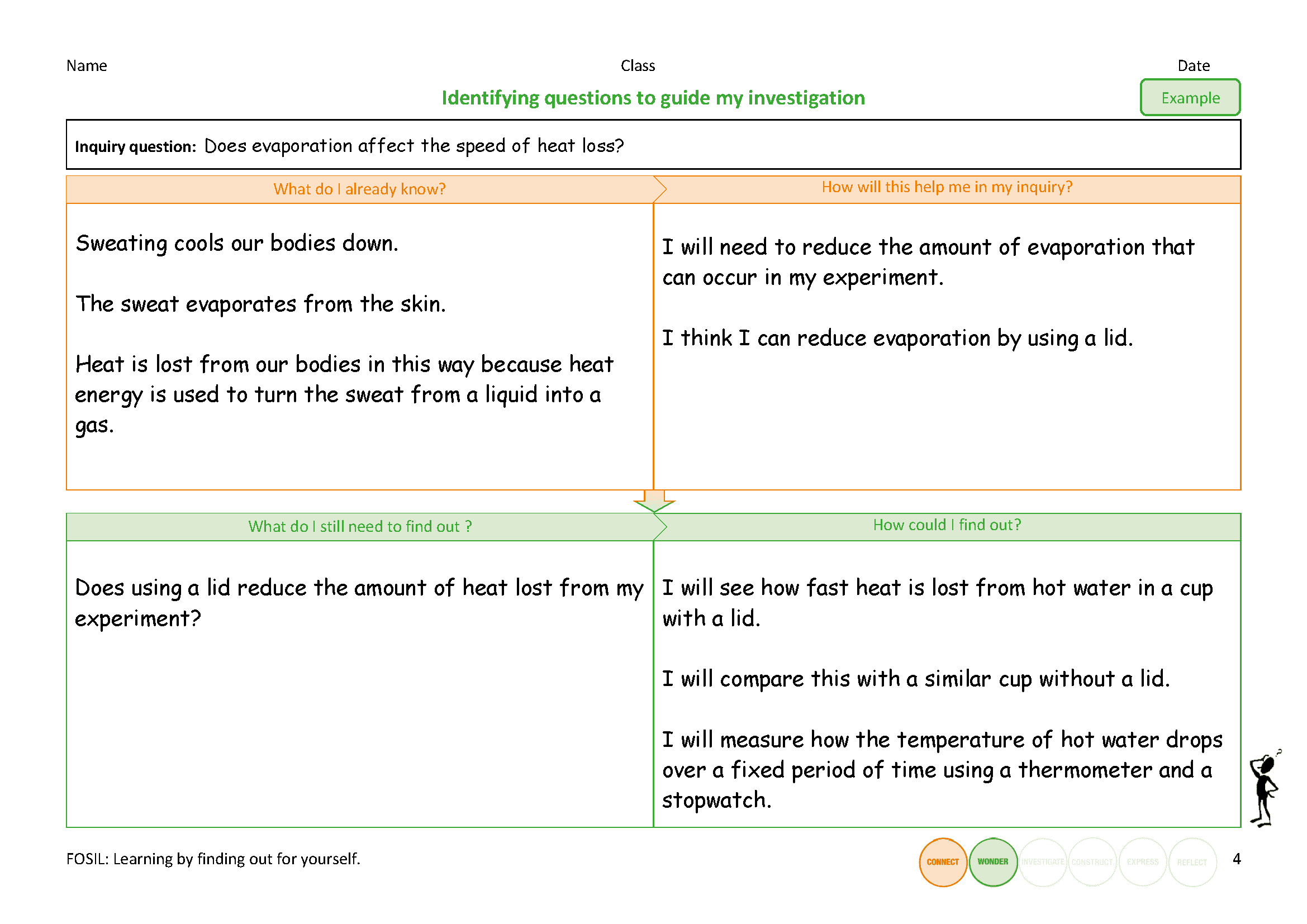

As this is a guided inquiry, the students were given a suggested question to guide part of the investigation – Does evaporation affect the speed of heat loss? – and this graphic organiser is filled in to help students understand the process. The colours on the graphic organisers help students understand where they are in the Cycle – orange is CONNECT and green is WONDER – which you can also see in the circles at the bottom of each page.

The example was deliberately taken from the part of the topic they usually find hardest (evaporation) to give them a good worked example for this, and then they were expected to think through, discuss and fill in similar graphic organisers for other methods of heat transfer (conduction, convection and radiation). There are four of these graphic organisers in order to ensure that students think deeply about what they need to find out and how they might begin to think about designing experiments to deepen their understanding (i.e, CONNECT gives rise to WONDER which guides the Investigation). It pushes them further and does not accept that their first answer is the only one.

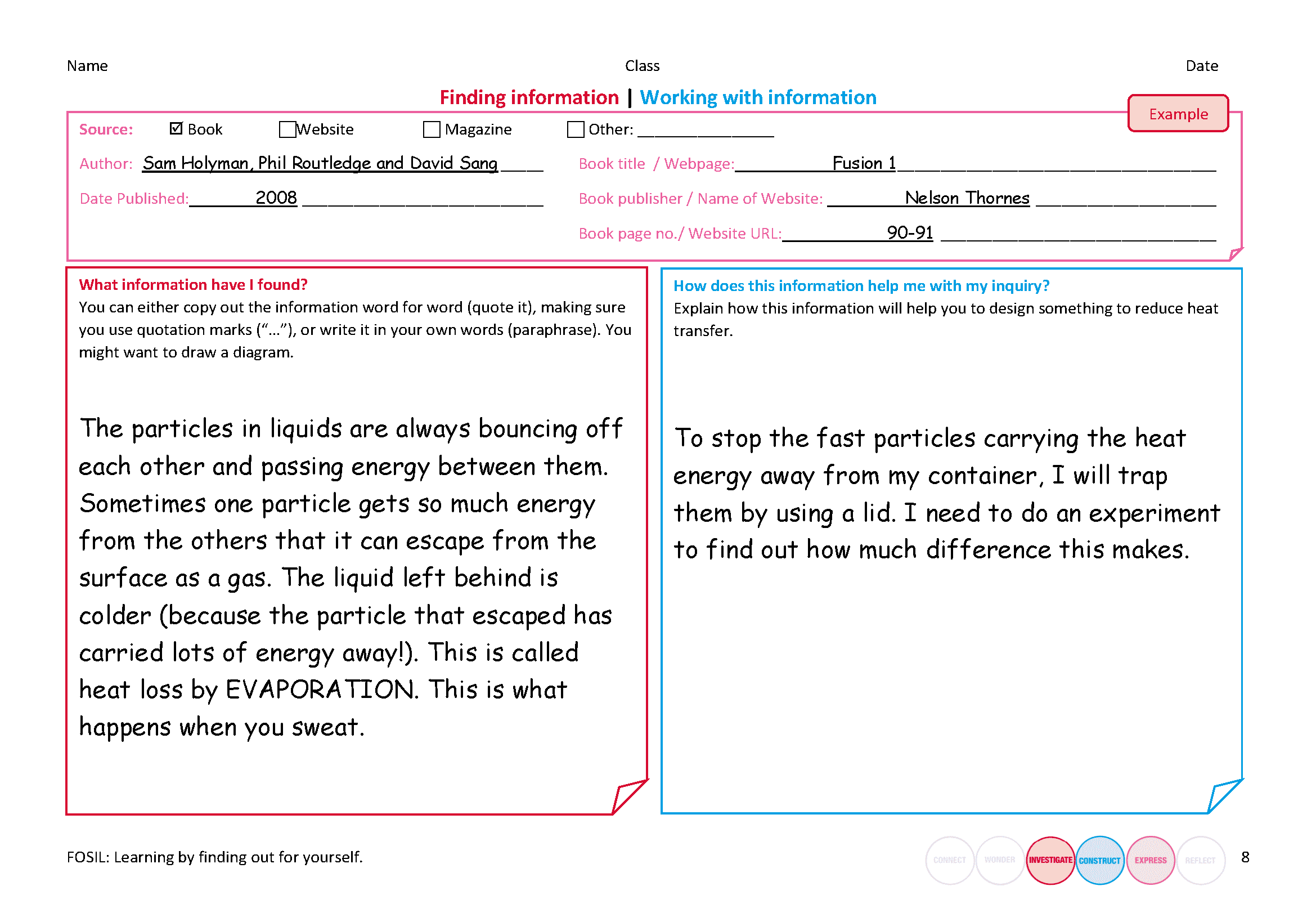

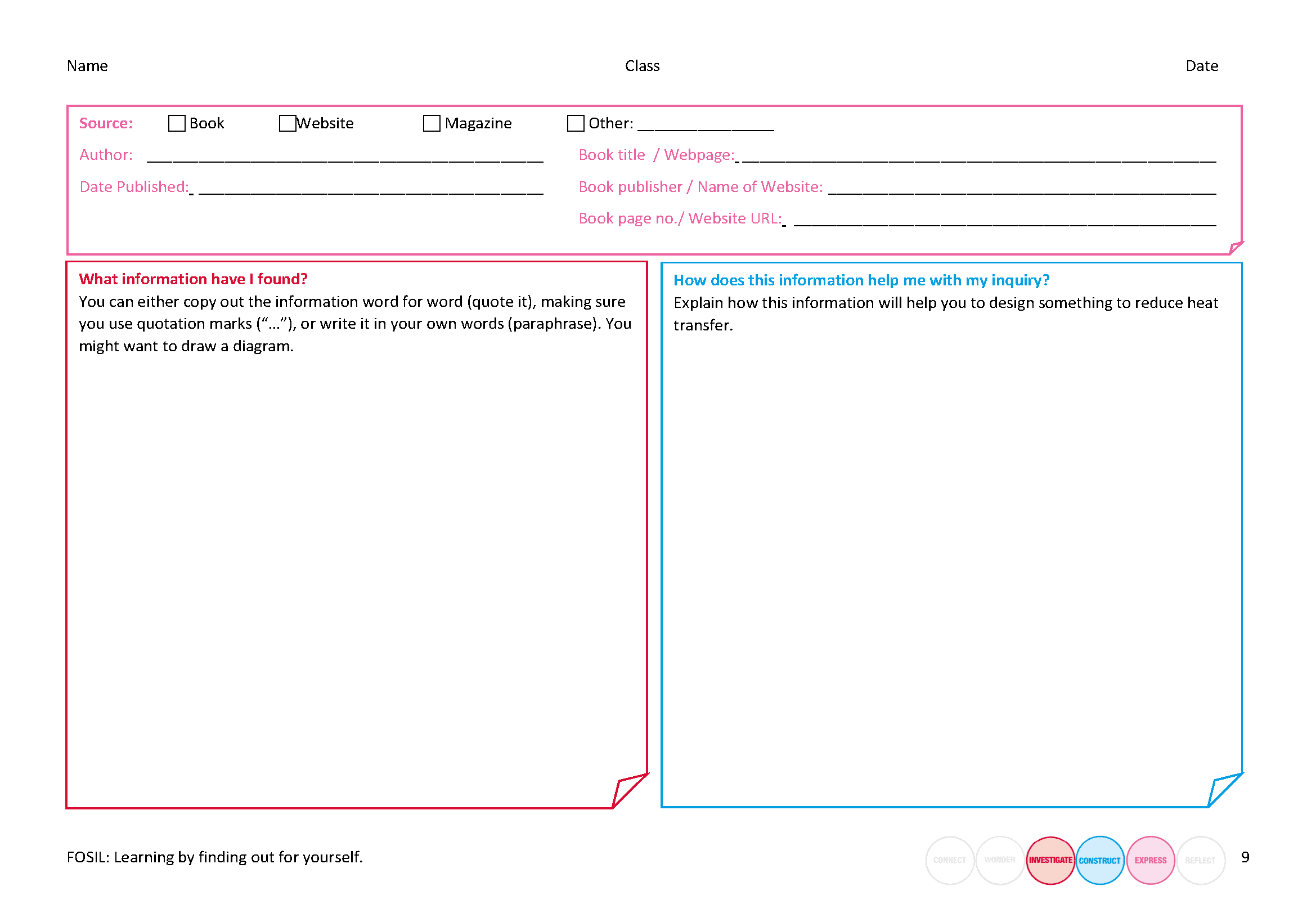

The students then move onto the Investigate stage where they start to find and work with the information they have found. There is another graphic organiser for this which is, again, colour coordinated and filled in showing the students that they are in the INVESTIGATE stage in red and moving into the CONSTRUCT stage in blue. The graphic organiser requires the student to write down where they got their information from, highlighting the information needed for their bibliography at the end of the project. As you can see on the left of the graphic organiser, students can cut and paste the information found if they wish to, encouraging them to use quotation marks. The right hand side of this graphic organiser guides them to the thinking process which helps the students to explain their learning and understanding by asking them to explain How does the information help me with my inquiry?

Again, students are given several blank graphic organisers that they are expected to fill in themselves. You will see that there is not an emphasis on the quantity of information but rather the purpose that the information serves in building knowledge and understanding. If the information found does not help them to answer their questions, then they are wasting their time. The teacher and librarian can clearly see at this stage if a student is struggling and needs more guidance and support.

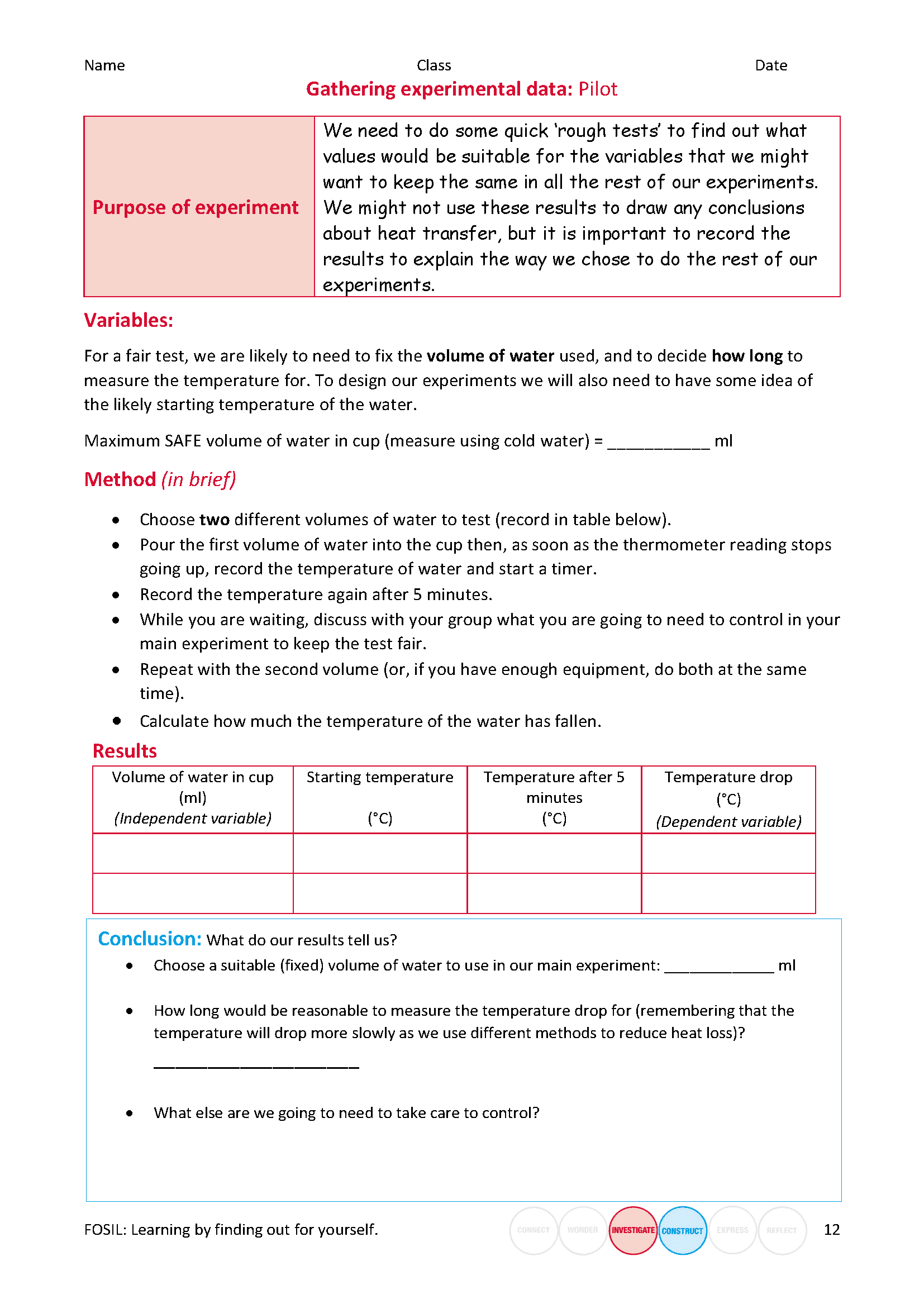

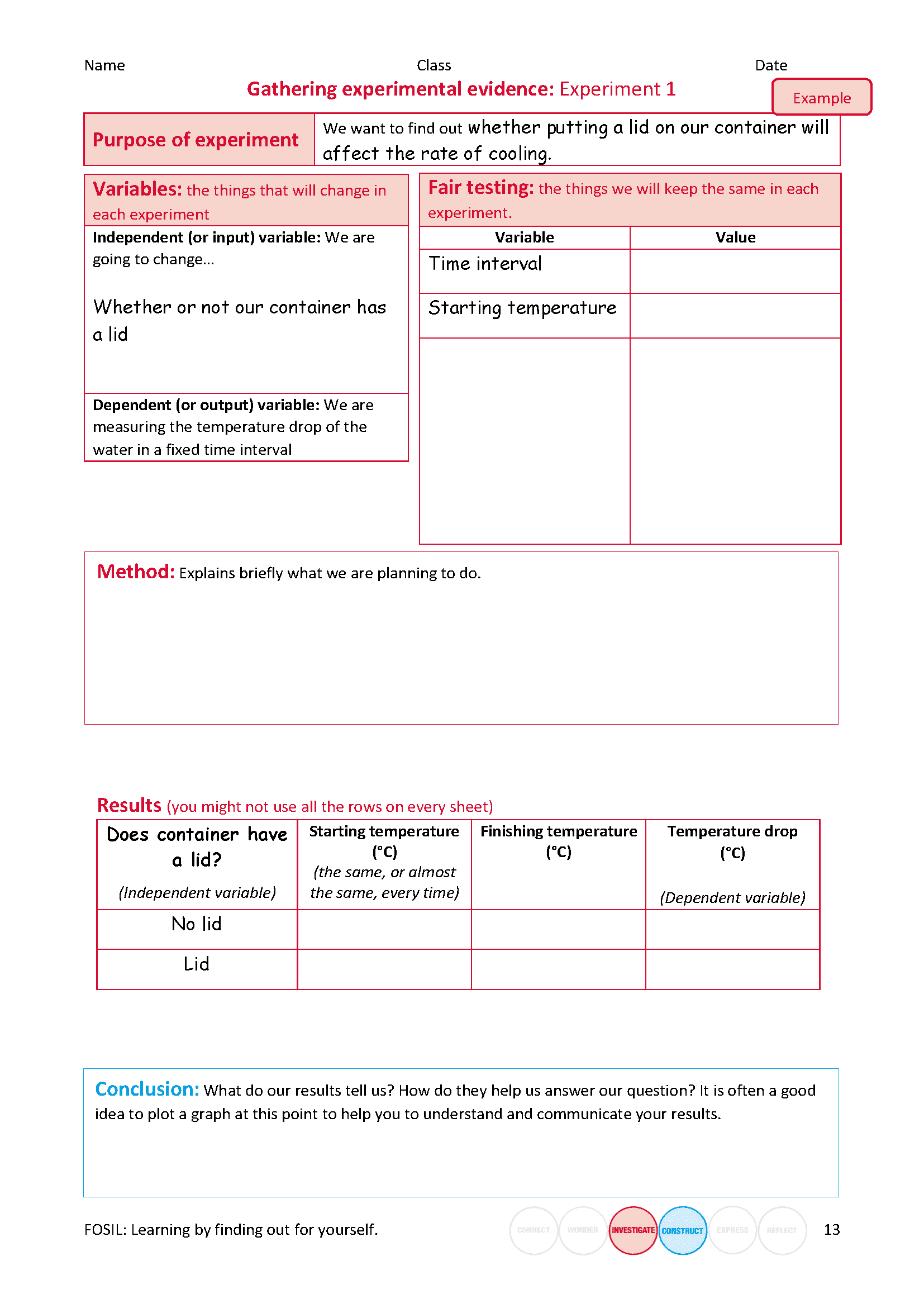

As this is a science investigation, it is leading to an experiment, so this next graphic organiser helps them understand the next part of the process. The circles at the bottom of the page are clearly showing that students are still in the INVESTIGATE and CONSTRUCT stage. This process is all about demonstrating how this experiment will work so guidance is important. For students of this age, one of the aims of the unit is to develop and cement student understanding of dependent and independent variables and fair testing, and how to lay out results clearly, so this is all modelled in the materials. For older students it is expected that some of this scaffolding would drop away as they gained confidence in experimental design. This experiment is clearly laid out with the purpose, variables, method, results and conclusion.

The students are expected to carry out 4 experiments. This first one is guided with another graphic organiser that is already filled in so that students can see an example of what is expected of them. They are then given another 3 blank graphic organisers to conduct their experiments themselves.

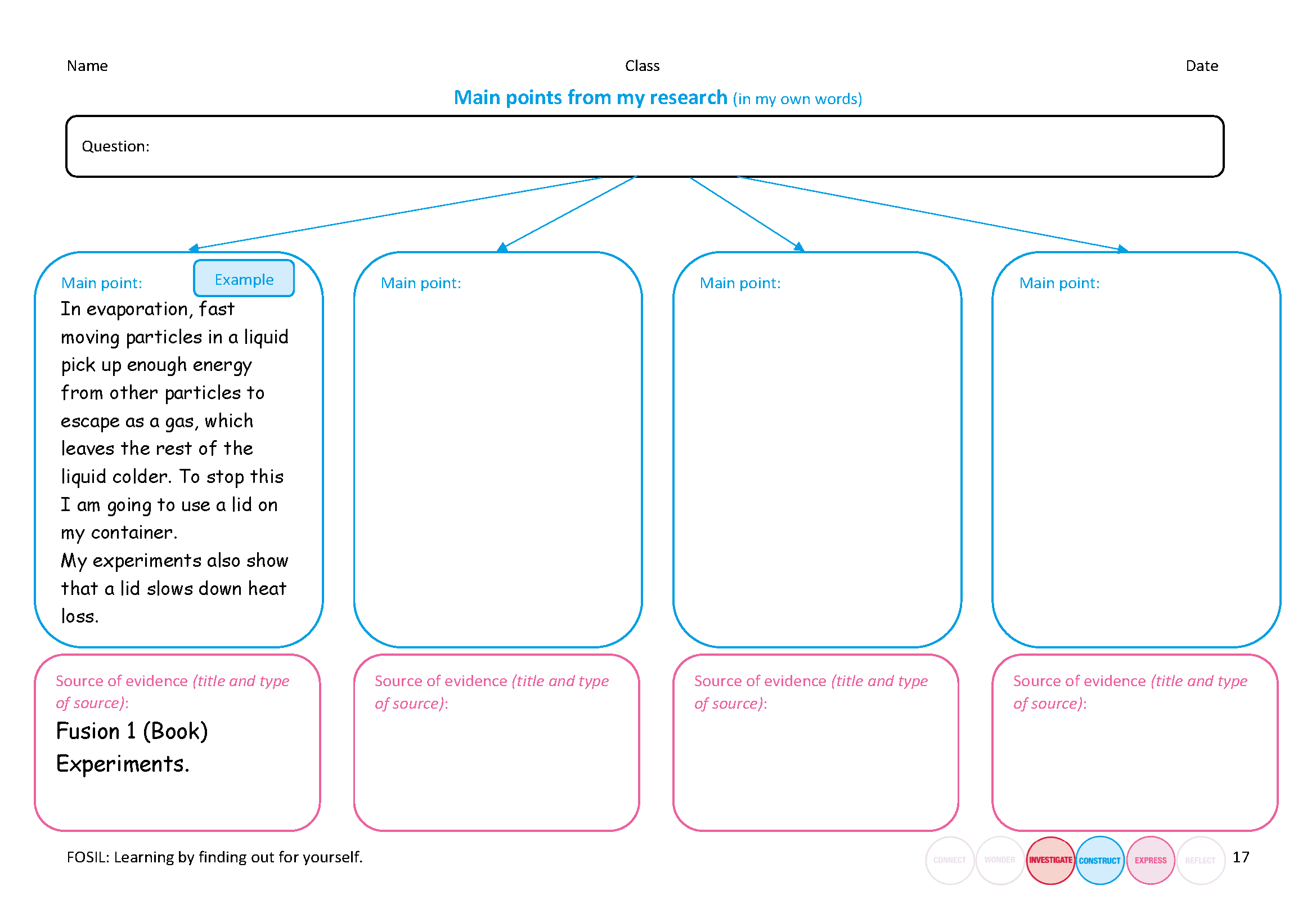

It is important that students can explain their own learning in their own words. This next graphic organiser brings them back to their question and helps them to focus on the main points. Again there is an example of what is expected in the first box. There is also guidance to ensure they provide evidence of where the information came from. The blue and pink shows the students that they are now in the CONSTRUCT and EXPRESS stage of the Cycle.

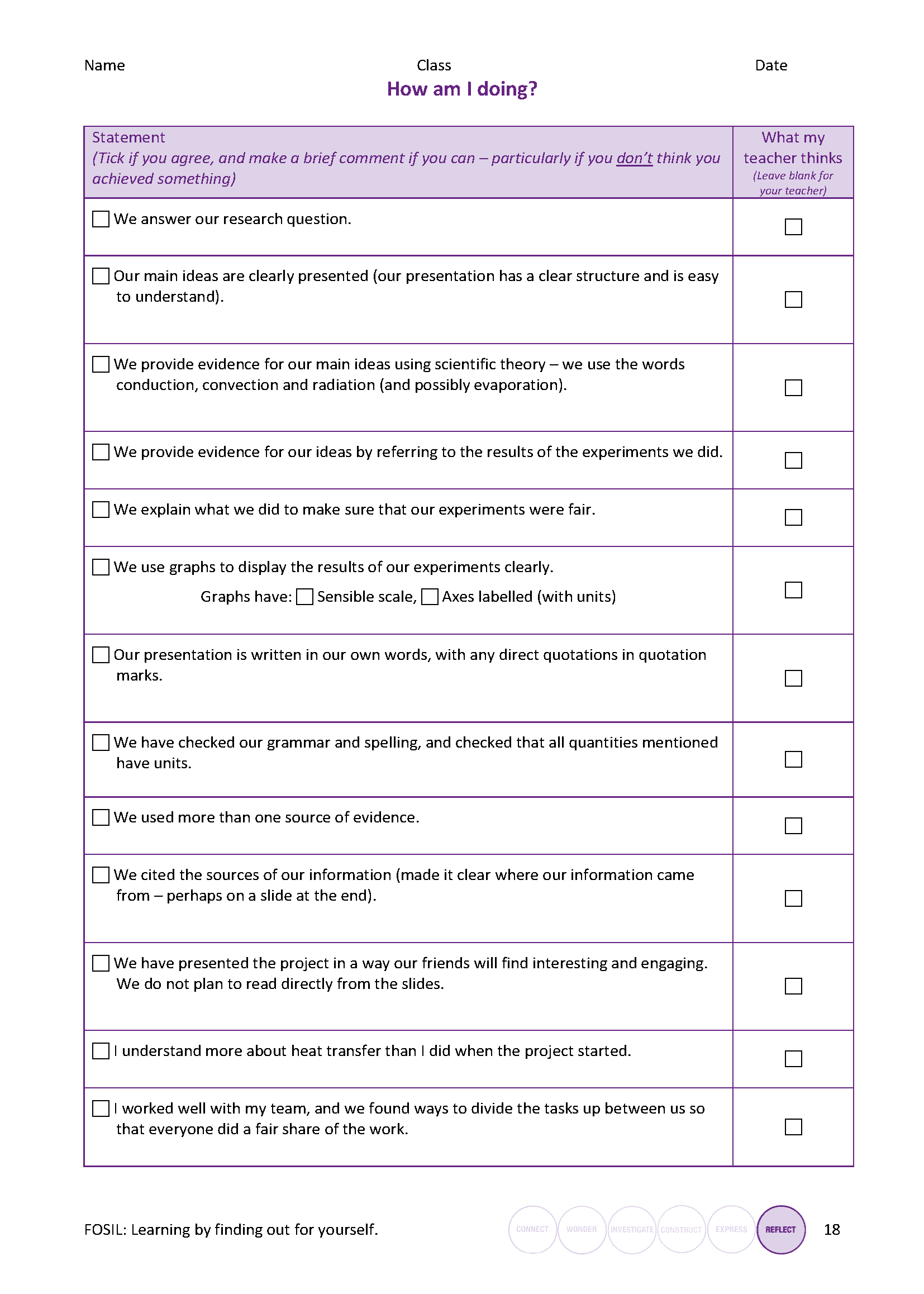

The final stage of the process is REFLECT, so the last graphic organiser requires students to reflect on how they are doing and to make sure they have done everything required for this inquiry in terms of product and learning process What I did well, Why was it good?, What could have been better? and How can I improve next time? It is important to allow students to assess themselves and then to be able to compare this with teacher assessment because this can be an excellent way to pick up misunderstandings and misconceptions. It can be very helpful to know whether a student didn’t do something because they felt they couldn’t, or ran out of time, or whether they genuinely believed they had done it because they didn’t understand the instruction (e.g. If they thought the scale on their graph was sensible but the teacher disagreed, this is the start of an important conversation).

Some of the graphic organisers you see above are based on a design developed for an English Science Fictional Writing inquiry and this, along with the consistent FOSIL colour scheme (which is used throughout the school, so some of the students would also have encountered it in Year 6, and all in English, Computer Science and during an off-timetable Community Day) brought a level of familiarity and continuity to the project. The students could both already recognise the process and begin to understand that it was not subject-specific, and the colour scheme helped them to internalise the inquiry process as the stages became more familiar to them. The familiarity reduced the amount of teaching time on how to use the resource which meant they could focus on teaching content.

Jenny, brought her own insight to this project: “Without the prompt to slow down and think about what they are about to do and why they are doing it, before they get their hands on the equipment, experimental design will likely be reactive and driven by the first piece of equipment that catches their imagination rather than thoughtful and systematic and driven by an understanding of theory. This is similar to the drive later in the inquiry cycle to get on with the EXPRESS stage rather than spend time constructing a new understanding based on the information they have found – which is why these are two critical stages for intervention and scaffolding”.

How the collaboration worked.

Jenny and Chris worked together to create the inquiry journal, deciding on what examples the students would need. Jenny brought the understanding of the inquiry process to this project, especially through CONSTRUCT. This helped students to understand why they were doing what they were doing and not focusing solely on the experiment. As Jenny had more experience in understanding the time that inquiry takes within the different stages, her expertise helped guide the process and Chris, the subject specialist teacher, found that having a non-subject specialist look at the planning very useful.

Collaboration between the teacher and the librarian in designing the process meant that they both benefited from each others specialism. The opportunities to share expertise and knowledge led to a project that was engaging and beneficial to the students’ information-to-knowledge learning journey.

To access this inquiry journal, follow this link https://fosil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/1F-111111-Crest-Heat-Transfer-Journal.pdf and to download a Word document that you can edit for your own purposes, follow this link https://fosil.org.uk/resources/?fosil_title=crest

The outcome of this project

Jenny told me that they could see an immediate improvement in the presentations as they were more varied and interesting. Previously every presentation was almost identical, whereas now students were given the freedom to explore different ideas as long as they covered the same theory. One pair did an amazing series of home experiments with baked Alaska, for example, and others investigated topics such as safely transferring organs for donation.

The biggest impact was seen in top and middle students who were clearly making stronger connections to the theory; however, improvement was seen across the whole year group. It was noted that there was still more work to be done on the REFLECT and EXPRESS stages. For example, there still needed to be a stronger mechanism to publicly (but sympathetically) challenge incorrect theory at presentation stage to avoid propagating misconceptions. This was an issue before FOSIL was used and is a problem with treating presentations as summative rather than formative assessment. Overall FOSIL certainly made a positive impact on student learning and highlighted areas for further improvement in the future.

To read more about this project you will find a discussion on the FOSIL Group Forum here https://fosil.org.uk/forums/topic/yr-7-inquiry-project-in-science/

Other projects

In my next article I will be talking through an example of how FOSIL is being used in A-Level Politics. However, I want to highlight that there are many inquiry journals available on the FOSIL Group website that you can freely download and edit for your own purpose, with credit of course. I would also encourage you to talk to your school librarian about these projects and ask for help and support. All the readymade inquiry journals can be found here https://fosil.org.uk/resources/ – just scroll through the pages to see them all, or use the search facility at the left of the screen.

Teaching was never meant to be a DIY job and bringing in the expertise of your school librarian could make all the difference to your students.

References

- CREST Awards. (2018). Inspire through STEM accessed 17/03/2021 https://www.crestawards.org/

- Krajcik, Joseph S., and Phyllis Brlumenfeld.(2006) “Project-Based Learning.” In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, edited by R. Keith Sawyer, pp. 317-334. New York: Cambridge.

- Lance, K.C. & Maniotes, Leslie K. (2020). Linking Librarians, Inquiry Learning and Information Literacy. Accessed online 7th January 2021 https://kappanonline.org/linking-librarians-inquiry-learning-information-literacy-lance-maniotes/

- Larmer, John, davide Ross, and John R. Mergendollar.(2009) PBL Starter Kit: To-the-Point Advice, Tools and Tips for Your First Project in Middle or High School. San Rafael, Carlif.: Buck Institute for Education.

- Tytler, Prof. Russel(2019). Inquiry vs direct teaching for interdisciplinary STEM accessed 01/03/2021 https://deakinsteme.org/blog/inquiry-vs-direct-teaching-for-interdisciplinary-stem/

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.