Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project

Home › Forums › Inquiry and resource design › Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project

- This topic has 8 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated 5 years, 3 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

9th June 2020 at 6:23 am #4485

We are in the process of reviewing the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project (FOSIL ISP), which is an ideal opportunity to reflect on what the FOSIL ISP is, and why it matters.

The FOSIL ISP has existed in some form for more than 20 years, perhaps since the foundation of the Smallbone Library in 1994.

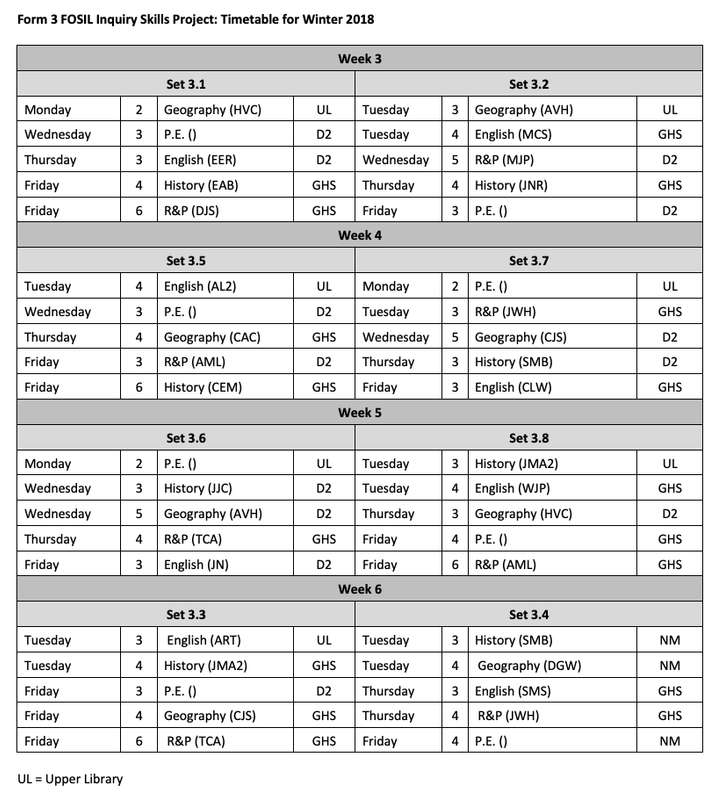

In its current form it consists of 5 x 50-minute lessons for each Year 9 set (there are currently 8 sets). These 5 lessons are taught by a Librarian and are drawn from English, Geography, History, Physical Education, and Religion & Philosophy. All 5 lessons are taught within a single week and 2 sets are taught concurrently, which means that all Year 9 pupils complete the Inquiry Skills Project within the first half term (see below for the 2018 timetable) – this requires an enormous effort on our part, but it lays an important foundation that I will discuss further. Sets are accompanied by their subject teachers.

We are fortunate on a number of levels to be able to offer the FOSIL ISP, but, as with all of our choices, given more or less limited resources, it is a question of priorities – my priorities now are practically identical to when I worked in school library on my own.

The FOSIL ISP serves a number of complex purposes:

- Approximately half of the students in Year 9 are new to the School. This means that they are unlikely to have encountered FOSIL as a model of the inquiry process, or inquiry as an approach to learning (unless, in the latter case, they come from an IB PYP and/ or MYP background), while the students they join will be increasingly familiar with both, especially since we became an IB MYP candidate school. The first purpose of the FOSIL ISP is, therefore, integration and consolidation, which is complicated by the fact that Year 9 is both the last year of the 3-year IB MYP and increasingly the first year of a 3-year (instead of 2-year) concern with the GCSE public examinations, after which students will have the choice of the IB DP or A-levels.

- The FOSIL ISP therefore also serves the purpose of transition, which in these circumstances presents us with a challenge: how to continue developing the mindset and skillset that will enable students to pursue inquiry more effectively and with greater independence within an instructional paradigm that does not have this as its end, and therefore favours different, often antithetical means? While this challenge must ultimately be dealt with at a more senior level, the FOSIL ISP still represents an important stage in the progressive and systematic development of this mindset and skillset in a way that is as useful as possible to both students and colleagues in other departments.

The FOSIL ISP, therefore, represents our most ambitious attempt to go beyond the “traditional library skills of locating resources and creating a bibliography” to providing students with “a framework of the inquiry process [and structuring] teaching around a framework of the literacy, inquiry, critical thinking and technology skills that students must develop at each phase of inquiry over their years of school and in the context of content-area learning” (Stripling, 2017, p. 52).

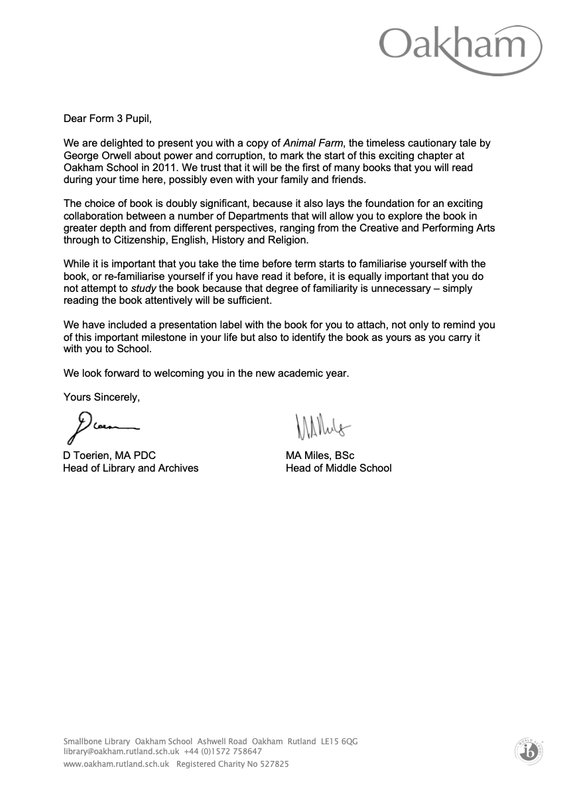

Since 2011, the FOSIL ISP has been linked to a fiction book that all incoming Year 9 students will have been given to read over their summer holiday. The choice of book was governed by a number of considerations, including: the extent to which it enabled meaningful links between different subjects (especially those that the FOSIL ISP drew on); how accessible it was likely to be to Year 8/ 9 students in terms of content, difficulty, and length; how enjoyable it was likely to be, and; cost. Our most successful choice, given these considerations, was Animal Farm.

In 2018 we made the decision to link the ISP to the Year 9 World Word I Battlefields Trip to France, which is an interdisciplinary collaboration between a number of departments, and also allowed us to collaborate with the School’s Archives. This decision dramatically narrowed our choice of book, and we settled on Line of Fire: Diary of an Unknown Soldier (August, September 1914), which worked well.

Problems with availability required us to choose a different book in 2019, and we settled on Dear Jelly: Family Letters from the First World War, which also worked well.

The first lesson serves as both an introduction to FOSIL and the FOSIL ISP, and the PowerPoint presentation that the lesson is based on may downloaded from here.

I will reflect on the workings of the FOSIL ISP, as well as its likely evolution, tomorrow.

Bibliography

Stripling, B. (2017). Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment. In S. W. Alman (Ed.), School librarianship : past, present, and future (pp. 51-63). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield

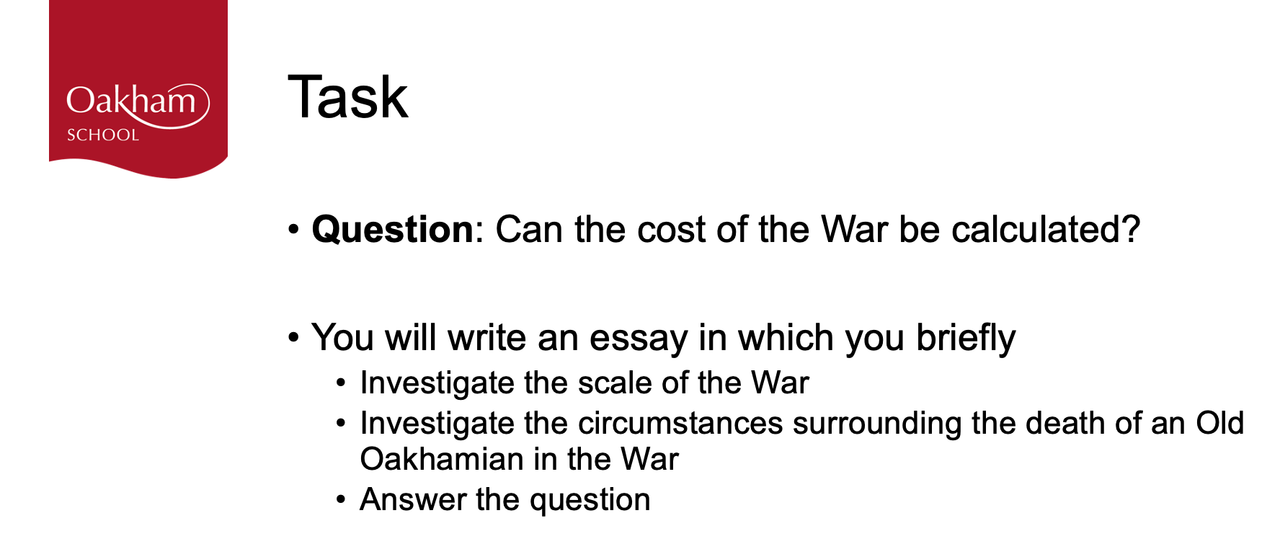

11th June 2020 at 8:07 am #4487The task, as outlined in the PowerPoint presentation from the first lesson, is:

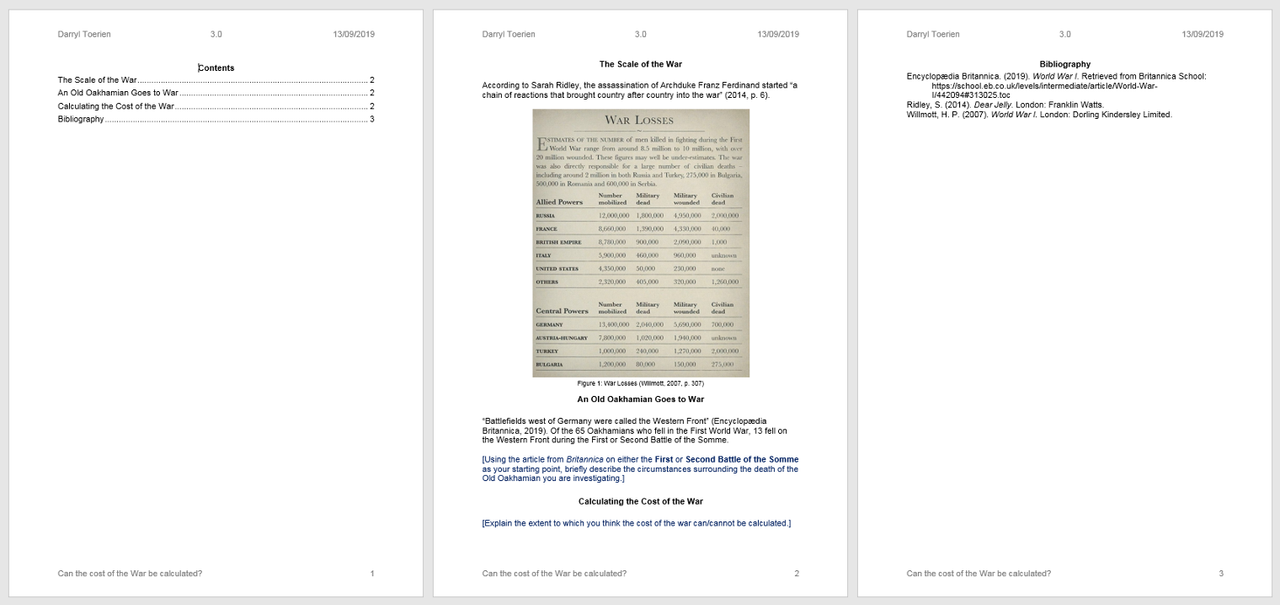

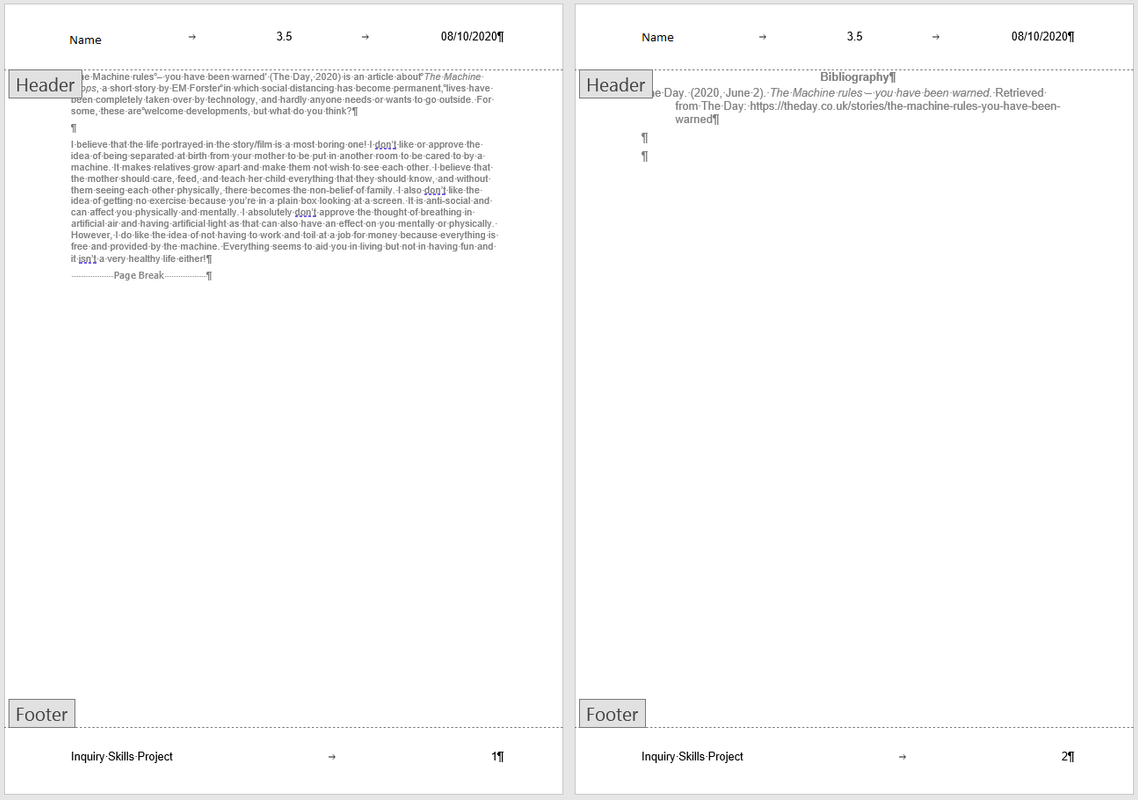

The essay that they produce will be based on our Academic Writing template, which is a simplified version of our Oakham APA template that we developed for the IB DP Extended Essay, and will resemble this:

The FOSIL ISP, as explained in the previous post, serves to introduce/ remind Year 9 students of the FOSIL inquiry process by way of a task that steps them through the inquiry process, and to consolidate/ teach foundational inquiry skills.

If, as in the case of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (ESIFC), we were working in an environment where we could be pretty certain that students new to the School in year 9 would be arriving with the same or very similar mindset and skillset, then the particular skills that we focus on in the FOSIL ISP might more closely follow the ESIFC continuum. As it is, the FOSIL ISP equips students with the following foundational inquiry skills, amongst others:

- Create a 3-column Header and Footer, including the date and page number (in the Microsoft Word application rather than the online version, which lacks functionality that is essential for academic writing, such as creating a Table of Contents and a Bibliography)

- Use Styles to create and maintain a Table of Contents (which requires page numbers)

- Cite and reference a book and website according to APA Sixth Edition

- Construct knowledge from information in the book and website

- Create and maintain an APA Sixth Edition Bibliography

- Insert an image of a table of data that is captioned, cited and referenced as above

- Extract information from data in the table, and construct knowledge from that information

- Distinguish between primary and secondary sources, and use both in an investigation

- Construct knowledge from information in those sources

There are two things to point out immediately:

- This is a big ask of student new to Year 9, especially in the time that we have available, but each year it less of a big ask for those students who are new to Year 9 from our Year 8, because we are more effectively developing this inquiry mindset and skillset progressively and systematically in Years 6, 7 and 8.

- We have a wide range of ability in Year 9, including students who have English as Additional Language (EAL), and all produce a more or less thoughtful essay that demonstrates the skills listed above.

For reasons beyond our control, the link to the World War I Battlefields Trip (see previous post), although very successful from our perspective, is no longer possible. While this development is regrettable, the resources that we produced for the Battlefields Trip, and those produced by the Archives, will still be useful on the Trip.

This development is compounded by the uncertainty surrounding the opening of schools in September due to COVID-19. It is unlikely at this stage that we will be able to source and post a suitable book that we can base the FOSIL ISP on, which is a pity, but, as Jamie Baker says, “real innovation [is] solving problem after problem after problem with grace and ease … which inoculates a school from becoming irrelevant,” and some solutions are already suggesting themselves to me. I will explore these later.

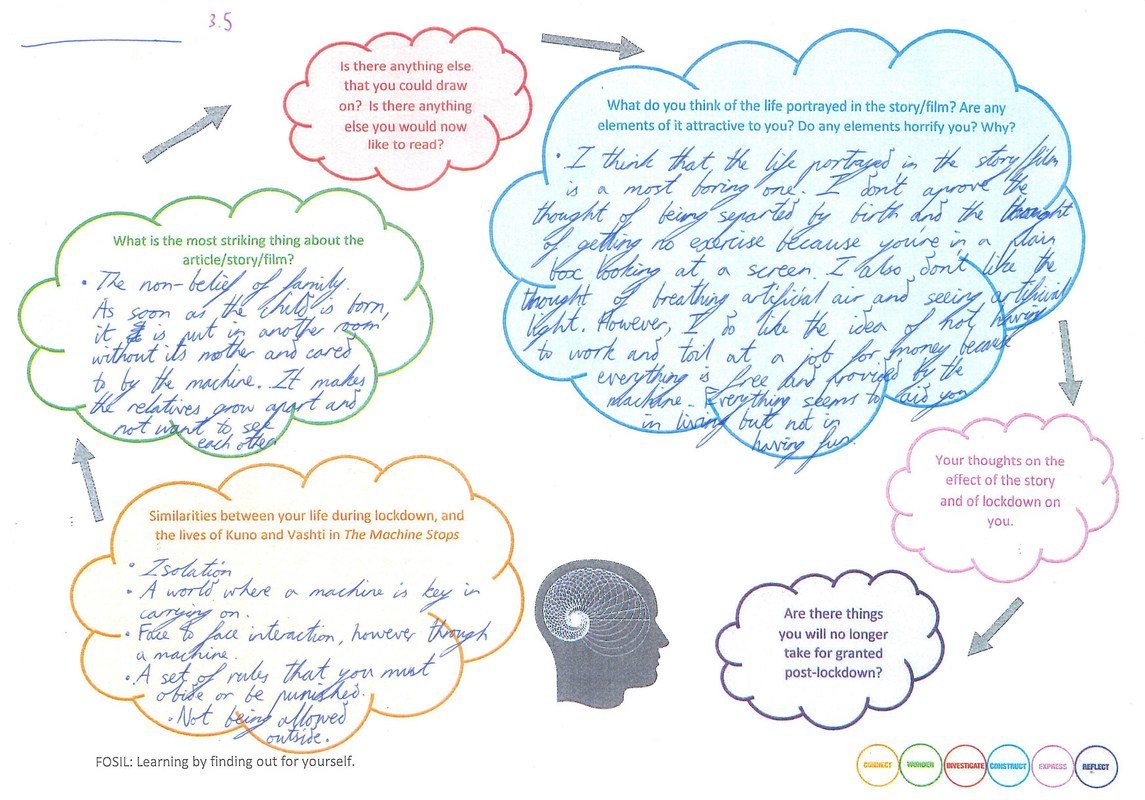

15th June 2020 at 5:54 am #4491I have added notes that a colleague made while observing these lessons, as well the two FOSIL resources that we use (these resources are what Barbara Stripling (2017, p. 57) refers to as graphic organizers and serve the purpose of “formative assessment [that is] integrated into inquiry-skills instruction”).

Bibliography

Stripling, B. (2017). Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment. In S. W. Alman (Ed.), School librarianship : past, present, and future (pp. 51-63). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield

17th June 2020 at 6:19 am #4493

17th June 2020 at 6:19 am #4493Needing to redesign the Form 3 Inquiry Skills Project without reference to World War I – which means rethinking our choice of book – and in the uncertainty of what school might look like in September – which means rethinking our delivery – is both a challenge and an opportunity.

An aspect of the Connect phase that is often neglected, often due to time constraints, is background reading, and providing students with a book to read over the summer is an ideal way to extend this phase in a meaningful way. If the book is chosen well, there is a good chance that this reading will also be pleasurable. Logistical problems surrounding a physical book encouraged us to be inventive.

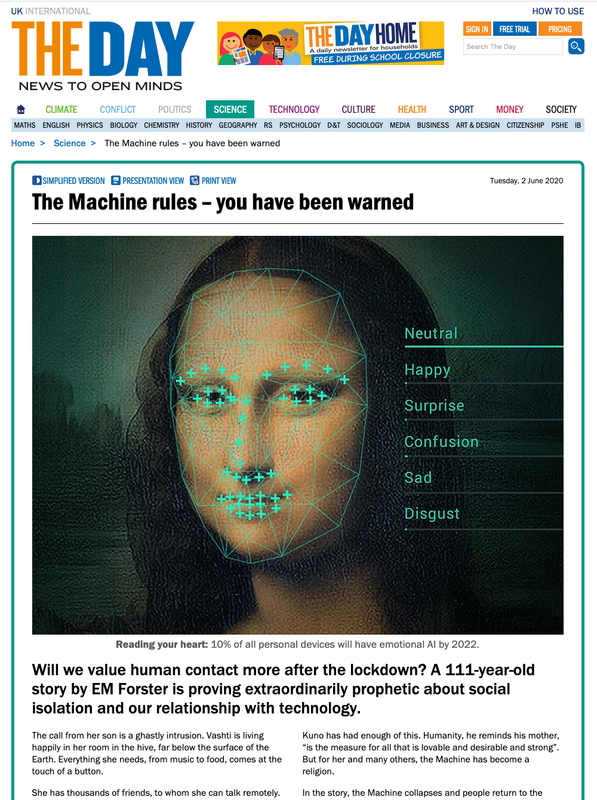

Lucy identified an excellent article in The Day, which we subscribe to, titled The Machine rules – you have been warned.

This article in particular has a number advantages:

- It asks a profound question – Will we value human contact more after the lockdown? – that lends itself to inquiry, which is “a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world, [and] as such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created” (Galileo Educational Network). It is worth noting in this regard that the spirit of inquiry – as “a dynamic process of … coming to know and understand the world” – gave birth to the library and the library remains its natural home, even if it is not always welcome in the library. This, in turn, sheds light on the fundamental purpose of a school library, which is to enable understanding through reading in the broadest possible sense of the word. This, I think, is also why the excellent Ideal libraries: A guide for schools says that “libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin … libraries are more often than not where learners begin inquiry, either by design or their needs.”

- It does so through the lens of science fiction short story by E. M. Forster – The Machine Stops – a genre science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson refers to as the literature of our time, and from which it derives its power, which is to reflect on the present from the safety of the future. Of The Machine Stops, Will Gompertz (Arts editor at the BBC) recently wrote: “[It] is not simply prescient; it is a jaw-droppingly, gob-smackingly, breath-takingly accurate literary description of lockdown life in 2020. If it had been written today it would be excellent, that it was written over a century ago is astonishing.”

- It is available online for free, but may be printed for offline reading if a subscriber.

- It is (short 1 page), accessible to a wide range of ability and rich in thought-provoking links (including the BBC article by Will Gompertz above and the full text of The Machine Stops below).

- It links to a full text version of The Machine Stops, which is freely available online as a PDF. The story, which should be optional, would stretch the intellectually curious and ambitious, although there are numerous audio versions that are freely available online, such as this BBC dramatization (44m12s), which should make the story itself accessible to a wider range of ability.

- With the shift in focus to science fiction, it will also be interesting to see what those Year 9 students who have come up from our Years 7 and 8 are able to draw on during the Connect phase, given that they will have undertaken the Year 7 English Inquiry – Science Fictional Writing.

As the purpose of the FOSIL ISP is not just to give our Year 9 students an opportunity to inquire, which would be like letting them swim with the fishes, but to make them more effective inquirers, delivery of the ISP also needs to take into account the demands of progressively and systematically developing the underlying skillset (see previous posts).

Barbara Stripling, who led the development of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum that FOSIL is based on, powerfully describes what we are trying to achieve:

[Enabling] student-driven, active inquiry where learners are motivated to find out about something that interests them by asking authentic questions, investigating multiple and diverse sources to find answers, making sense of the information to construct new understandings, drawing conclusions and forming opinions based on the evidence, and sharing their new understandings with others. Inquiry is about developing personal meaning connected to prior knowledge, not accumulating information or adopting someone else’s knowledge. That is the dream but not the reality for most children in our educational system. … Providing a framework of the inquiry process is only the first step in empowering students to pursue inquiry on their own. The next step is to structure teaching around a framework of literacy, inquiry, critical thinking, and technology skills they must develop at each phase of inquiry over their years of school and in the context of content area learning.

Bibliography

International Baccalaureate Organization. (2018). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organization.

Robinson, K. S. (2008, November 15). Opinion. New Scientist, p. 48.

Stripling, B. (2017). Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment. In S. W. Alman (Ed.), School librarianship : past, present, and future (pp. 51-63). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

24th June 2020 at 8:57 pm #4528Darryl, I’ve read through the F3 ISP posts and I’m very excited to read The Machine Stops! To me, this looks much more immediately relevant and accessible than the battlefields link.

It seems to me that these resources illustrate really clearly what FOSIL is all about. I think another point I would like to emphasise is that they cut through the false dichotomy of skills vs knowledge. By treating the inquiry skills as a progression, and working on them throughout the school in meaningful activities such as these, our pupils are better equipped to select and use information to develop an understanding of concepts. They have access to what Michael Young calls ‘powerful knowledge’. What is more, they get to practice learning independently, skills which have been particularly important over the last few months of disrupted schooling.

It is obvious to me (from a student research point of view) that the skills the senior pupils need to cope with the demands of the IB Diploma Extended Essay, the Extended Project Qualification and other independent project work and coursework in the Sixth Form build up from the activities they meet in the Year 9 Inquiry Skills Project and earlier.

15th September 2020 at 4:43 pm #17707The Year 9 Inquiry Skills Project starts next week.

Due to COVID-related timetable constraints the Project will be delivered this year in one 90-minute double English lesson rather than five 50-minute single lessons drawn from English, Geography, History, Physical Education, and Religion & Philosophy. The choice of English is deliberate, because roughly half of Year 9 will have experienced the Year 7 English Inquiry – Science Fictional Writing and it will be interesting to see whether they have a greater appreciation of the value of science fiction in helping us to make sense of our increasingly science fictional present.

I will post the lesson outline and rationale later this week.

I have included below the letter that introduced this year’s Project to Year 9 pupils and their parents.

22nd September 2020 at 10:38 am #19323

22nd September 2020 at 10:38 am #19323The Year 9 Inquiry Skills Project faces a number of challenging design and delivery constraints this year, not least of which is the shift to Timetable B, which presents us with one 90-minute double lesson instead of five 50-minute single lessons. As outlined in the first post, the Project serves a number of complex purposes, which include introducing students who are new to the school in Year 9 (Grade 8) to the FOSIL inquiry process and equipping all Year 9 students with foundational and developmentally appropriate literacy, inquiry, critical thinking and technology skills that enable the stages of the process. The fact that a growing number of these skills are technology-dependent, either by definition or in use, necessitates the use of computers, which has practical and logistical implications. Finally, the lesson needs to cater for both in-person and online learning.

The lesson, which will be recorded, will be introduced through a PPT presentation (see LibGuide below, but without external access to the embedded video for copyright reasons). The remainder of the Lesson will be supported by a LibGuide, which will also include the content of the PPT presentation for the benefit of students who may miss the lesson for various reasons.

The lessons consists of 3 parts.

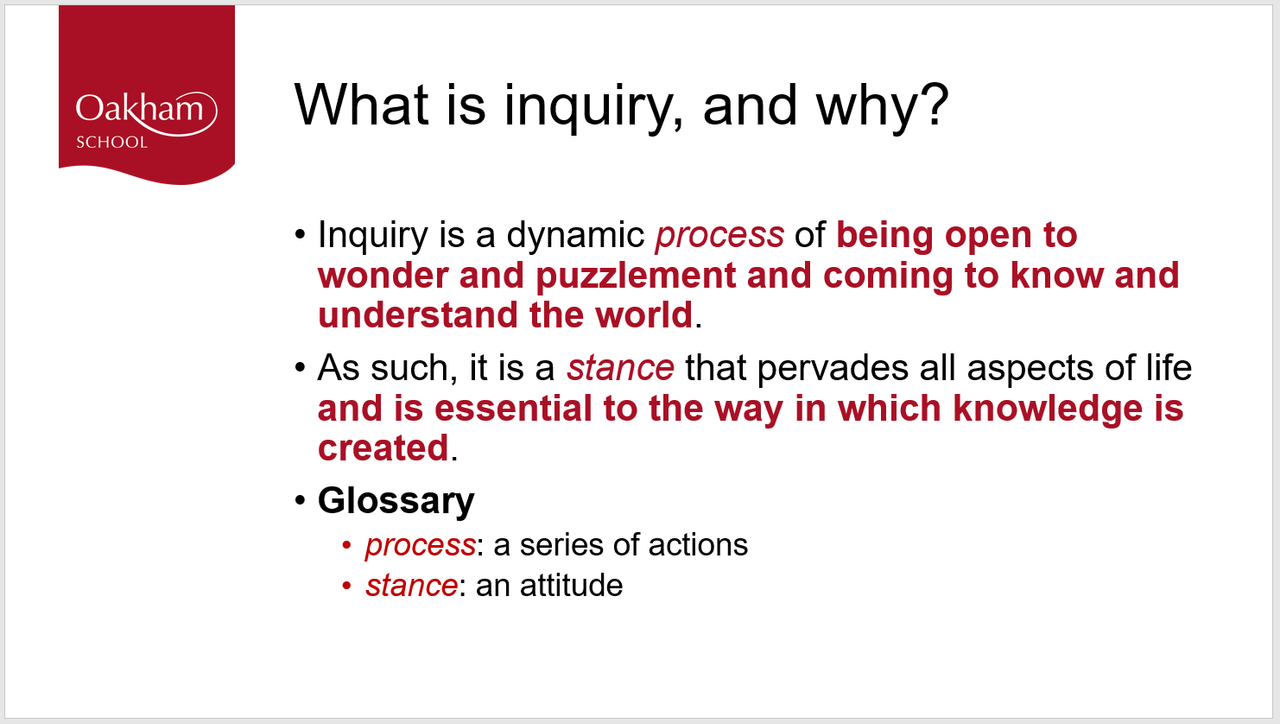

Firstly, an introduction to/ explanation of the FOSIL inquiry process. New this year is an explanation of what inquiry is and why inquiry matters using the excellent description of inquiry from the Galileo Educational Network’s website:

This is important because inquiry, understood this way, is a fundamental human endeavour, and the heart of our task is to help our children to find their place in it. This sense is captured beautifully by Julian Astle and Laura Partridge in their RSA piece, Education for Enlightenment:

If we are to create a 21st century enlightenment, we need to educate our children for that task. That means inducting our children into the great conversation of mankind – the unending dialogue between the living, the dead and the yet-to-be-born; that this means introducing them to the best that has been thought, said and done, and equipping them to appreciate it, interrogate it, apply it and build on it.

Secondly, skills, which are focussed on being able to use our Academic Writing Template (see LibGuide), which includes citing and referencing in Word using APA style.

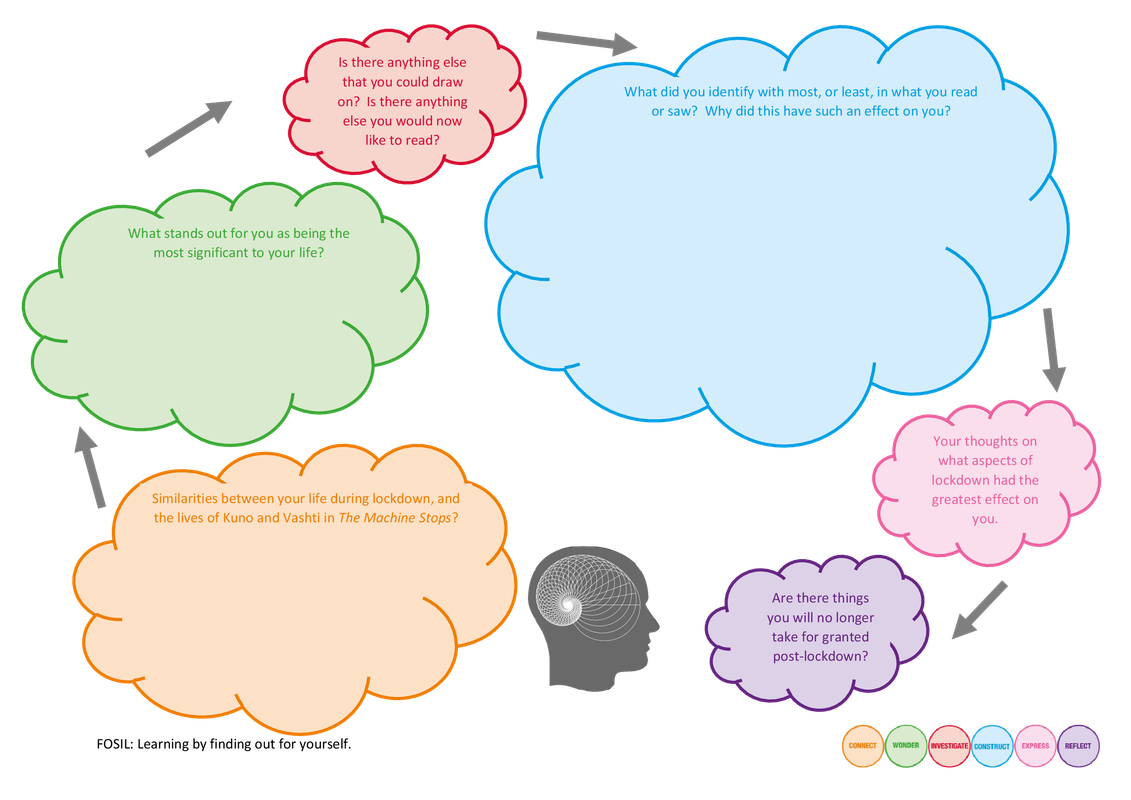

Thirdly, an opportunity to thoughtfully work their way through the stages of the inquiry process (see below) and write a personal response to their background reading, which asks whether we will come to value human contact more during these “interesting times” (see LibGuide)?

Achieving the above in 90 minutes will require a brisk pace, and I will post an initial reflection following our first two lessons on Thursday and Friday.

4th November 2020 at 12:49 pm #27293In the weeks leading up to half-term, we successfully saw each of the Year 9 classes as planned and so carried out this inquiry seven times. It never ceases to amaze me that in doing the same lesson with seven groups of 13 year olds can lead to such different experiences and outcomes. In part this is because we refine the inquiry as we go through it, get quicker at delivering it as we learn which parts are going to take that bit longer than planned, or even which elements can be left out altogether – either because we are covering skills they already know, or because we find they are not actually needed in order for pupils to complete the task. Partly it is relation to the setting of the classes, which in turn affects set sizes; to how long it takes all members of the class to find the correct room; to whether enough computers in the room are working properly to accommodate everyone. This year, the main factor turned out to be whether or not the pupils had managed, under the circumstances, the required background reading and so had an understanding of what we were talking about. We learned as we went along, getting the English teachers on board to encourage or require the reading of the article just before their lesson with us, even providing paper copies of it to one class the day before. Once they knew the background, engagement improved, contributions increased and the written work became far more considered. It was clear which class had been asked to read the E. M. Forster short story, as well as the article from The Day, and which class contained not one single pupil who had managed to even read the article.

While not every class reached the point of producing responses to the question using their beautifully set-up academic writing documents, another advantage of the structure used is that we have evidence of their thinking anyway – on the worksheet above, or a version of it as it too was tweaked as we went along – and the thinking stage is the one we are really interested in them having wrestled with in this inquiry.

11th November 2020 at 1:32 pm #28560Thanks, Lucy.

What amazes me, especially under these particularly challenging circumstances, is that all students have still emerged from this with a shared, more or less stable, foundation of knowledge of the inquiry process and key inquiry skills, in addition to what they learned from the article (and for some of them, from the short story). And as you touch on, it would have been interesting to see what difference actually having had the chance to read the article and, possibly, short story over the summer holiday would have made.

All students, then, managed to format their academic writing document and think their way through the inquiry process, and just over a third comfortably managed within the time constraints of the lesson to go on and respond to the question in writing (see below).

It would be helpful to identify where this foundation is likely to built on over the course of the year.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.