Barbara Stripling

Active 2 years, 3 months agoRole: Professor Emerita

Town/City: Philadelphia

Country: United States

Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

One of the reasons that I started developing the portraits is that I believe, first, that we (school librarians, classroom teachers) must always focus primarily on our students and their intellectual, social, and personal growth (rather than the library or library collection). That learner filter enables me to make good decisions about the library program, resources, and instruction. Secondly, I know that I need to be able to envision the learners I am trying to “create” in order to plan and implement a library program that builds students through a continuum of development. What does a second grader who has developed essential skills and attitudes look like? What is my role, as a librarian, in provoking and nurturing that development?

I have been pursuing my understanding about inquiry-based teaching and learning through the library for the last twenty years. My work on developing an inquiry process and a PK-12 continuum of skills (entitled the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum – ESIFC) has continued to be modified, adapted, and deepened as my own understanding has become more complex and nuanced. Two years ago, I worked with a group of stellar librarians in New York City to update the ESIFC and align it with new NY digital fluency standards and a new framework of cultural responsiveness. Hard work, but we shared our revised ESIFC and graphic organizers online through a Creative Commons license (https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc).

As I was facilitating that work, I realized that my philosophy about the librarian’s role in teaching and learning through the library had changed. I believe that school librarians must accept the responsibility for teaching the whole child – the critical and creative thinking skills of inquiry and literacy (independent learning), but also the whole-child attributes of self-identity, social and emotional strengths, cultural responsiveness, voice and agency, and a growth mindset. The group of NY City librarians did initial work on defining the whole-child attributes for grades 2, 5, 8, and 12. Those grades were selected because, in the United States, they are benchmark points in a child’s educational experience. I have continued the work and have developed a comprehensive alignment of specific skills and attitudes for each of the portrait attributes with the six stages of my inquiry process – Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express, Reflect.

All of those skills were already embedded in the ESIFC, but by explicitly listing them under their appropriate portrait attribute, we can see how we can teach a lesson to middle schoolers focused on Connect, for example, to enable students to state what they already know or assume about the problem or question (independent learning), and, during the same lesson, enable them to identify their own misconceptions (self-identity), understand how they personally connect to the topic (voice and agency), and discover different perspectives on the same topic (cultural responsiveness). It sounds a bit complicated, but many (most?) lessons we already teach touch on those personal attributes. With an intentional portrait focus, we can be explicit and let the students know how many skills and competencies they are learning beyond the content.

Because my goal is to engage and empower student inquirers, I wanted students to recognize their own empowerment. The next step, then, was to develop “I can” statements for each of the attributes. I think those “I can” statements can be shared with students before inquiry experiences, so that they recognize the skills they will develop through their own active learning. Typically, in the United States, students are told the content goals before a unit or lesson, but little mention is made of the skills they will develop. The “I can” statements turn the responsibility for learning over to the students and give them a picture of success.

I plan to continue devcloping tools and strategies for whole-child teaching guided by the portraits. I know I will continue collaborating with Darryl and Jenny to provide models of units and lessons for others to adopt and adapt. We are interested in your own reactions to this work and your thoughts about next steps.

I have enjoyed reading your planning conversation from my perch in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, because I am thinking about some of the same questions about teaching and learning through inquiry. First, I wanted to say how much I appreciated the guiding question for the whole unit – Why do people live near volcanoes? That question lifts the whole experience from fact-finding to constructing personal meaning from facts and ideas. You will engage students in understanding the people and context of the area around volcanoes and forming evidence-based opinions. That’s powerful.

I was thinking that one possible way to deepen students’ understanding of the impact of living near a volcano would be to let them choose a role in pursuing their investigations – reporter, government official, survivor/local resident. You can probably find short accounts from each of these perspectives. I would think the answer to the question about why people live near volcanoes would differ depending on the point of view and that would further personalize and deepen the students’ understanding about volcanoes.

I wish I could be there to see the students’ engagement in this interesting inquiry investigation. Thanks for sharing.

I am so pleased that the conversation about inquiry-based teaching and learning is continuing through this Forum. I enjoyed creating my presentation and sharing the ongoing questions that Darryl and I are pursuing through our weekly conversations. We have so much left to learn and develop to bring inquiry-based learning alive in all of our schools. Darryl set an important context for our work in libraries – the culture of education itself through the entire school. The implementation presentations by Jenny and Joe were phenomenal. Yes, we can do this! And they are proof that we, as educators, can change our whole approach to teaching and make a huge difference in the quality of learning for our students. Their presentations (one with both of them; the other by Jenny alone) were definitely worth getting up at 5 AM (my time).

I am looking forward to our continuing conversation. I have much to learn.

I agree with you, Elizabeth, that the inquiry journey starts in primary school. I think that’s when we start building an inquiry stance by fostering a sense of wonder about the world, as well as what the children are learning in school. I know that most primary school teachers encourage and honor their students’ questions and curiosities, but I have been thinking about how the teachers might build an inquiry stance from that questioning. I think adding two factors to their teaching responses to questioning would transform ad hoc questioning into inquiry:

- giving students time and resources to find answers to their questions so that the focus shifts from blurting out miscellaneous questions to following up on questions that really matter to the students and giving them the chance to learn something new (perhaps by setting aside a short inquiry time every Friday, for example, when students can pursue answers to their questions and write or draw pictures in their inquiry journals); and

- helping the students recognize the joy of their own thinking by asking followup questions that cause students to think about their own thinking (“What made you ask that question?” “What do you think the answer will be?” “Do you have other questions about this same topic?”).

I think most primary teachers naturally incorporate class discussions throughout the day, while they are reading stories, having a share-circle time, or teaching new content in social studies and science. They could naturally blend in the two strategies above to those interactive sessions and I think the students will be well on their way to developing an inquiry stance.

Bénédicte and Camille,

Thank you so much for sharing your well-designed INSET Day workshop. I know from personal experience how challenging it can be to design a workshop that presents new ideas while at the same time engages participants in making their own meaning. You have done that. I loved your descriptions for the phases of inquiry, because you provided real insights into the thinking of students during each phase. I recognized my students in your comment that stronger students like to skip Connect and Wonder to go directly to Express because they think they already know everything they need to complete the assignment. Actually, that insight into students’ desire to just “get it done and move on” led me directly to working with teachers on designing assignments. I wanted students to develop new understandings, so I had to be sure that the assignments themselves demanded thinking and could not possibly be a simple narrative of general knowledge or something copied directly from a source.

Because I found so much success in working with teachers to design creative and thought-provoking final products, I was struck by your statement that copy-and-paste research is “common where the focus is on the product and not the learning experience.” I definitely agree with you about the importance of the learning experience, but I also recognize the value of a well-designed (and not copyable – is that a word?) final product for motivating students to engage fully in the learning experience.

Your first activity was intriguing to me. I think everyone would benefit from seeing different perspectives on inquiry and the skills that would be prioritized for different subject areas. I once did a huge chart that compared literacy skills that would be most important in English, social studies, science, and math. For example, perspective and opinion were valuable in English and social studies, but largely replaced by accuracy and credibility in math and science. I imagine you found some interesting comparisons in your teachers’ responses.

I hope that your teachers got a good start on creating a scheme of work with at least 3 FOSIL phases. I loved the way you set this up for success. First, the teachers were collaborating with a small group from the same department to select a unit they already do. That’s brilliant. I imagine you had great buy-in because teachers were recognized for their expertise and given the chance to make their unit even better. The second piece I loved was that you asked them to add only 3 phases. That’s certainly more realistic than the way I’ve been explaining inquiry design. I usually go into a long explanation of the need to scaffold student work in some of the phases, because you can’t teach all the skills necessary for high-quality inquiry in every unit. Your approach works much better and allows teachers to follow their own instincts about how to make the learning flow.

Thank you so much for sharing your work. I learned a great deal and look forward to our continued conversation.

3rd May 2021 at 4:32 pm in reply to: Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning #51023I have drafted some responses to the questions posed to us by The Day. It’s amazing how powerful it is to have a conversation among colleagues who bring different perspectives to it. I tend to assume that everyone defines concepts and terms the same way that I do. When someone asks me to clarify what I am thinking, it helps me think more deeply about my own assumptions.

Questions from The Day

What is inquiry-based learning?

Inquiry-based learning is grounded in centuries of educational theory and practice as well as in international documents. The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) has issued IFLA School Library Guidelines (2nd revised edition, June 2015. Editors Barbara Schultz-Jones and Dianne Oberg) and they offer an overview of inquiry-based learning and its major concepts:

Instructional models for inquiry-based learning generally use a process approach in order to provide students with a learning process that is transferable across content areas as well as from the academic environment to real life. These models share several underlying concepts:

- Student constructs meaning from information.

- Student creates a quality product through a process approach.

- Student learns how to work independently (self-directed) and as a member of a group.

- Student uses information and information technology responsibly and ethically.

The Galileo Educational Network (GEN) has been the professional learning arm of the School of Education at the University of Calgary for 22 years. GEN’s first principle is “Stewarding the intellect through inquiry-based learning.” GEN offers a definition of inquiry:

Inquiry is a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world. As such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created. Inquiry is based on the belief that understanding is constructed in the process of people working and conversing together as they pose and solve the problems, make discoveries and rigorously testing the discoveries that arise in the course of shared activity.

Darryl Toerien and I have enlarged the GEN definition to develop the following working definition:

Inquiry is a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis of responsible participation in community (Stripling and Toerien, 2021).

Why is it so important?

The goal of any educational system is to enable students to become independent learners for life. Young people who pursue an inquiry stance have learned the skills, attitudes, and questioning mindset to negotiate the complexities of their academic and personal lives. They have the self-confidence to make their own decisions, draw their own conclusions, and pursue their own futures. They recognize their responsibility to participate actively and ethically as members and contributors to their communities.

Inquiry is especially important in today’s fast-paced, information-glut society when every individual must sort through volumes of misinformation, disinformation, bias, gaps, and information lacking authority, accuracy, and reliability. The questioning lenses and attitudes of inquiry will enable students to challenge what they read, see, and hear and develop new ideas and understandings that are valid and accurate.

What’s FOSIL Group’s theory on how we develop young people’s thinking skills?

We develop young people’s thinking skills by 1) validating their sense of wonder and questioning; 2) explicitly teaching them the thinking skills of inquiry and providing many opportunities for guided practice; 3) integrating the teaching and use of thinking skills into knowledge-acquisition experiences, so that students are not just receiving information delivered by others, but they are developing their own understandings based on challenging and interpreting what they read or hear; and 4) teaching students to be mindful of their own thinking process, so that their self-reflections lead to further development of their thinking skills.

What’s your view on how we teach young people to think more critically about world issues?

Certainly, an essential piece of teaching students to think more critically about world issues is to teach them the critical thinking skills embedded in the inquiry process. We must also enable students to develop a critical stance on the world, confident to question why, so what, what else, and what if any time they encounter a new or intriguing idea.

Along with attention to students’ thinking skills, we must frame their encounters with world issues to focus on the underlying themes and concepts and to help them make connections to their own lives. Student could read about famine in a specific area of the world, for example, but they may not do more than accumulate a few facts unless they strive to understand the essential problem or question (e.g., the underlying causes of famine; the relationship between famine and climate, government, or other factors) and they connect as fellow humans to those who are experiencing famine.

How can teachers apply inquiry-based learning when using The Day in the classroom?

The Day – for those whose budgets allow for it – is an amazing resource for librarians and content-area teachers, both for its intriguing articles and for its application to inquiry-based learning. Because of the framing of articles by essential questions and extension resources and activities, the articles inspire focus questions in multiple content areas. The same article could be used by teachers of science, math, language, and social studies to probe ideas in those content areas inspired by the article. Examples of those curriculum connections for one article, “A Fable in Search of a Great Humane Vision,” are in the FOSIL Group Forum discussion, Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning (https://bit.ly/3ujkzu7).

Articles in The Day can be used effectively for one-lesson inquiry investigations and as opening provocations for larger inquiry units. In both cases, the teaching or scaffolding of appropriate inquiry skills is embedded as a way for students to develop deep understanding of the content and start drawing their own conclusions about the essential questions (as applied to the teacher’s curriculum focus). Examples of a lesson and a unit around the “Fable” article have also been posted to the FOSIL Forum discussion, Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning (https://bit.ly/3ujkzu7).

19th April 2021 at 10:08 pm in reply to: Thoughtful REACTionS to The Day: Framing Inquiry-based Learning #47022As Darryl and I started thinking about our presentation for The Day, we both realized immediately that many of the articles could be used to provoke deep thinking and inquiry across the curriculum. We also agreed that educators must frame and guide the learning experience to lift students beyond simple comprehension of the information in an article. A conceptual frame at the beginning of a learning experience will focus on the core ideas that will drive the instructional design. An inquiry frame introduces the major concept(s) to the students and, at the same time, opens the possibilities for student-driven inquiry guided by that frame or lens.

For me, a valuable frame that leads to inquiry is an essential question. I have always found essential questions somewhat difficult to write, because they force me to think deeply about the big ideas or concepts that underlie a specific topic. As an educator, essential questions make me a little uncomfortable, because I know that my students will never find the definitive answer (because there isn’t one). I value essential questions, however, because they provide direction, boundaries, and inspiration for inquiry investigations. They make me, as a continuous learner, excited to explore new ideas.

Darryl and I developed two essential questions that we could use to frame a learning experience with The Day article, “A Fable in Search of a Great Humane Vision.” I would choose one or the other, depending on the class in which I intended to use the article.

- What does it mean to be human?

- How might today’s actions and inventions predict the near and long-term future of humanity?

A second piece of framing that ensures that students focus on the content that is most important for specific curriculum objectives is defining a curriculum lens. From my perspective as a librarian with some insight into all curricular areas of a school, I identified possible curriculum lenses that could be used by educators across the curriculum. The classroom teacher and I, as librarian, would engage in a conversation to define the essential question and specific lens to frame our instructional design.

I developed a list of the possible curricular lenses.

Curriculum Area — Possible Lenses

English

- The synergy of science, humanity, and imagination in science fiction

- Science fiction conceptual themes:

- Humanity

- Community

- Power

- Progress

- Conflict

- The literary genre of science fiction

- Role of science fiction authors in world building

- Role of science fiction in mapping the future

Science – Biology

- Human development

- Genetics, cloning

- Free will vs. determinism

- Artificial intelligence

- Humans vs. animals

- Interplay between biology and psychology

Technology

- Dimensions of artificial intelligence

- Philosophical, ethical, religious implications

- Relation to humanness

- Intersection between humans and machines

- Impact of embedded coding

- Technological advances – who decides?

Social Studies

- Psychology concepts

- Social and emotional needs/competencies

- Relationships (e.g., friendships)

- Dispositions (e.g., empathy)

- Acceptance of status quo vs. choice to resist

- Sociology concepts

- Individual vs. group

- Social networking

- Community: what unites us, what divides us; inequality

- Civil unrest, protest

Arts

- Artistic expressions of humanity

- Painting and drawing

- Poetry

- Music

- Media

Darryl and I found the article in The Day so replete with possibilities for deep thinking, even in a limited, one- or two-day learning experience, that we had to restrain ourselves from continuing to add other ideas. We reminded ourselves to stay within the realm of the essential questions.

After deciding on an essential question and determining a curricular frame, educators are prepared to take the next step to design the instructional experience. Darryl is going to share our instructional designs for a limited experience (1-2 days) and an extended inquiry experience (8 days).

26th March 2021 at 3:45 pm in reply to: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment #40834The latest posts by Elizabeth, Stephanie, and Jenny have pushed me to think more deeply about evaluating online sources. I agree that we need to teach students how to evaluate the sources/websites they find and giving them specific criteria to consider is at least a starting point. I agree that laboring through all of the criteria for each source is time-consuming and perhaps counter productive (because students won’t continue with that beyond an academic requirement). But I also think there is value to giving students enough specific and detailed practice in using each of the criteria that they become habits of mind. I totally agree with Jenny that our goal is to make source evaluation second nature, so that students quickly decide which criteria are important to assess for each source and they can use specific strategies to make their own decisions about the value of a source.

Then I started thinking about the criteria themselves and ended up with some additional considerations that I am wondering about. When we check for authority (Jenny provided the important insight to look outside of the original source), I think students may need to check the authority of both the publisher/organization and the author (if named separately). For the publisher, students should consider point of view/bias and reputation. Both are very difficult to assess. For the author, students need to consider the authority in context. I will never forget working with students to determine authority and we discovered that the author had a PhD, but in a completely unrelated area to the topic at hand. This “authority” was actually offering his personal opinion rather than authoritative evidence about the topic.

The authority issue becomes even more complicated when an author or presenter is an authority on the topic, but offers information that is contrary to the bias of the publisher and therefore should not be dismissed as representing the publisher’s point of view. That happens occasionally in the US when a television network host interviews someone live (e.g., when Fox News, a very conservative news outlet, interviewed Dr. Fauci, a recognized expert in COVID). It’s hard for anyone to sort through the conflicting information to figure out what’s true (or mostly true). I think that’s why so many of us succumb to confirmation bias.

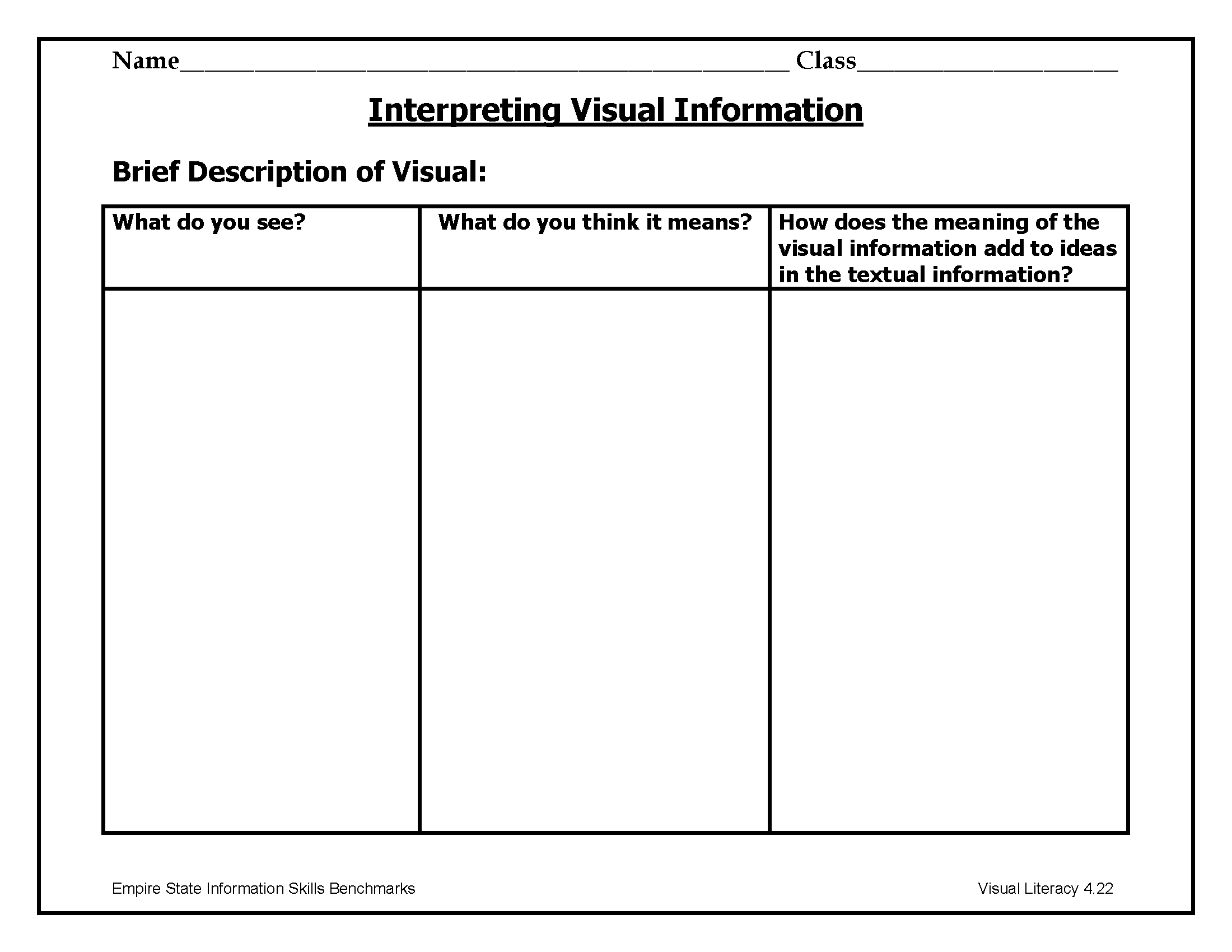

I loved what Stephanie said about judging a book by its cover. We all tend to do that, I think. Even librarians have figured out that, if we want our administrators to read our library news and reports, we need to package the information visually or in an easy-to-read format, because they are too busy to read in-depth narratives. Infographics have become increasingly popular as a way for librarians to communicate with administrators, parents, and even teachers. I think this is why I am convinced that visual literacy must be a part of our teaching, because all students are inundated with visual information and they are absorbing subliminal messages.

Your conversation has also caused me to think more deeply about purpose. I am not sure about how to teach students to determine a source’s purpose. How can we help students decide if the purpose is to educate, persuade, criticize, entertain, or editorialize? Once they decide, how do we help them determine the impact on the credibility and usefulness of the information? And, along those lines, how do we help students recognize their own purpose and how that impacts what information they gather and how they interpret it?

The focus on students’ purpose brings me to my next consideration about evaluating information. Much of our conversation has been about evaluating sources. After students have done that, they then need to evaluate and interpret the information within the sources. I think that’s when deep reading skills become so important. Especially in the digital world of live presentations, podcasts, and television broadcasts, students need to recognize that even reliable, authoritative sources might “publish” a segment that includes misinformation, biased opinion, or strategic gaps in information. Whew! It seems exhausting. This is where Jenny’s wisdom gives us a way forward: “what we are actually teaching students is a sense of healthy suspicion.”

We’ll talk more in a couple of days. I’m looking forward to it.

23rd March 2021 at 10:56 pm in reply to: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment #40307What an interesting discussion we are engaged in about inquiry in the digital environment. I have read each of your entries with great interest and find myself puzzling over many of the same issues as you. Although we know that there are many skills and attitudes that are important for inquiry learning itself, whether it is pursued in the print or the digital environment, I am intrigued by the new or enhanced competencies demanded by inquiry in the online context.

I would like to pose some areas that we might explore more deeply together in our conversation on March 28. I recognize the challenges inherent in each of these areas, but I am still trying to figure out how I might help students overcome those challenges. What practical strategies can we figure out together?

1. Visual literacy. The online environment uses visual images, placement, highlighting, color, and attention-focusing techniques to implicitly guide the reader’s sense-making. If something is set aside in a box or presented graphically, then the reader may automatically classify that information as more important than other information embedded in the text. The seduction of visuals may encourage our students to hop from one visual to the next, gathering superficial first impressions and losing the context of the surrounding text.

2. Homogeneity of online information. Darryl mentioned that, with the glut of information now available online, learners must shift their focus from simply finding information to assuming responsibility for determining the reliability of information. Part of the dilemma for students is that all online information can appear to be homogeneous, to have the same value and authority. Blogs, student projects, texts by both experts and nonexperts, organizational websites, opinion pieces, commercial messages – all can be designed to appeal and attract readers or at least clicks. Two aspects of the CRAAP test that Jenny referred to seem to be the most relevant to help students differentiate among seemingly equal sources – authority and purpose. How can we help students learn to determine both authority and purpose, select the most reliable information for their academic pursuits, and carry that discernment over to their personal online searching?

3. Diverse perspectives. I am troubled by the impact of the digital environment on the diversity of the content of the information that students find. I think it is difficult for students to find credible and authoritative information from diverse perspectives, both because it is difficult to figure out the search strategies that will yield equally valid information from different points of view and because we seem to be naturally inclined to succumb to confirmation bias. The lateral and linked nature of much online information offers students the opportunity to gather additional information by following the links in their initial source, but the linked information is, of course, written from the same perspective. How do we enable students to seek, find, and pay attention to diverse perspectives?

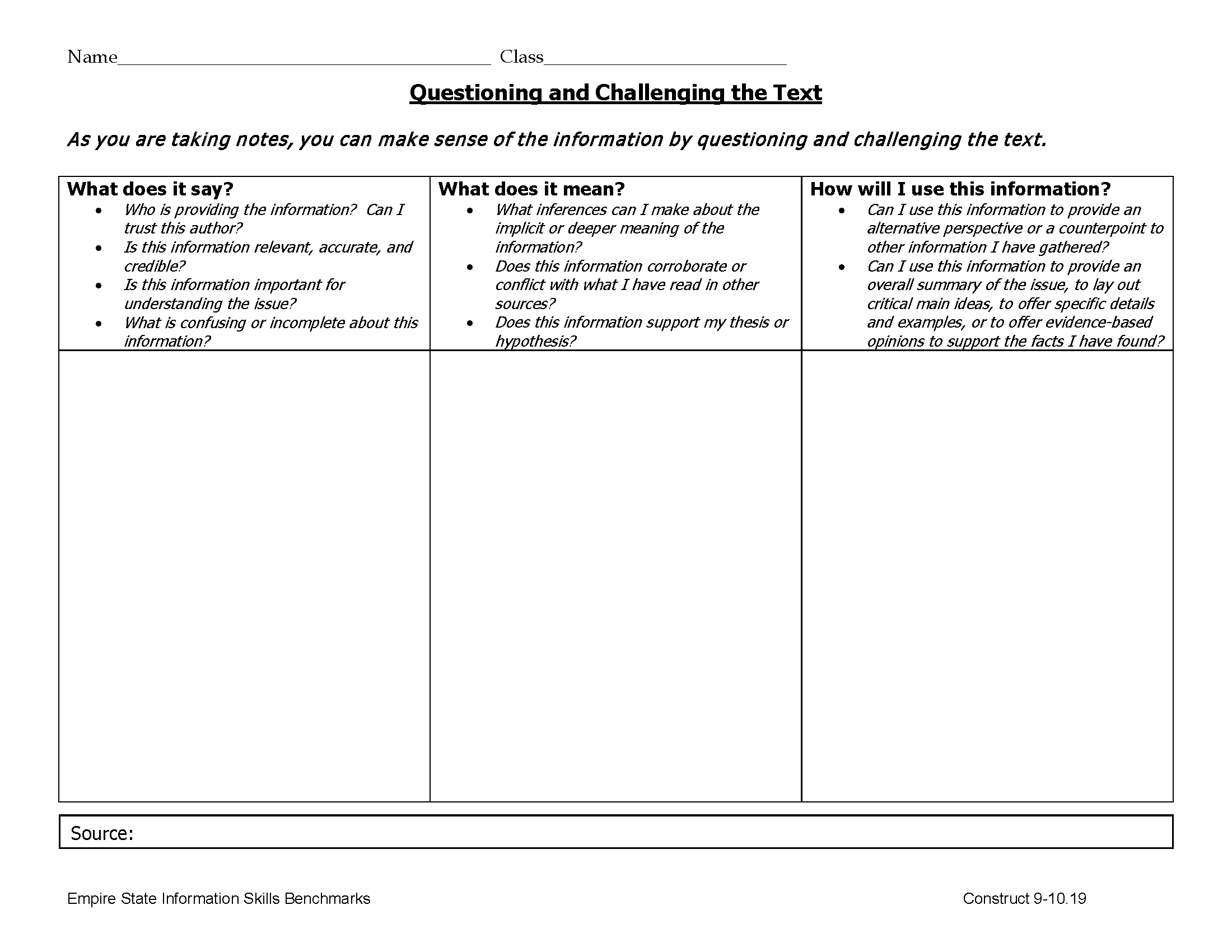

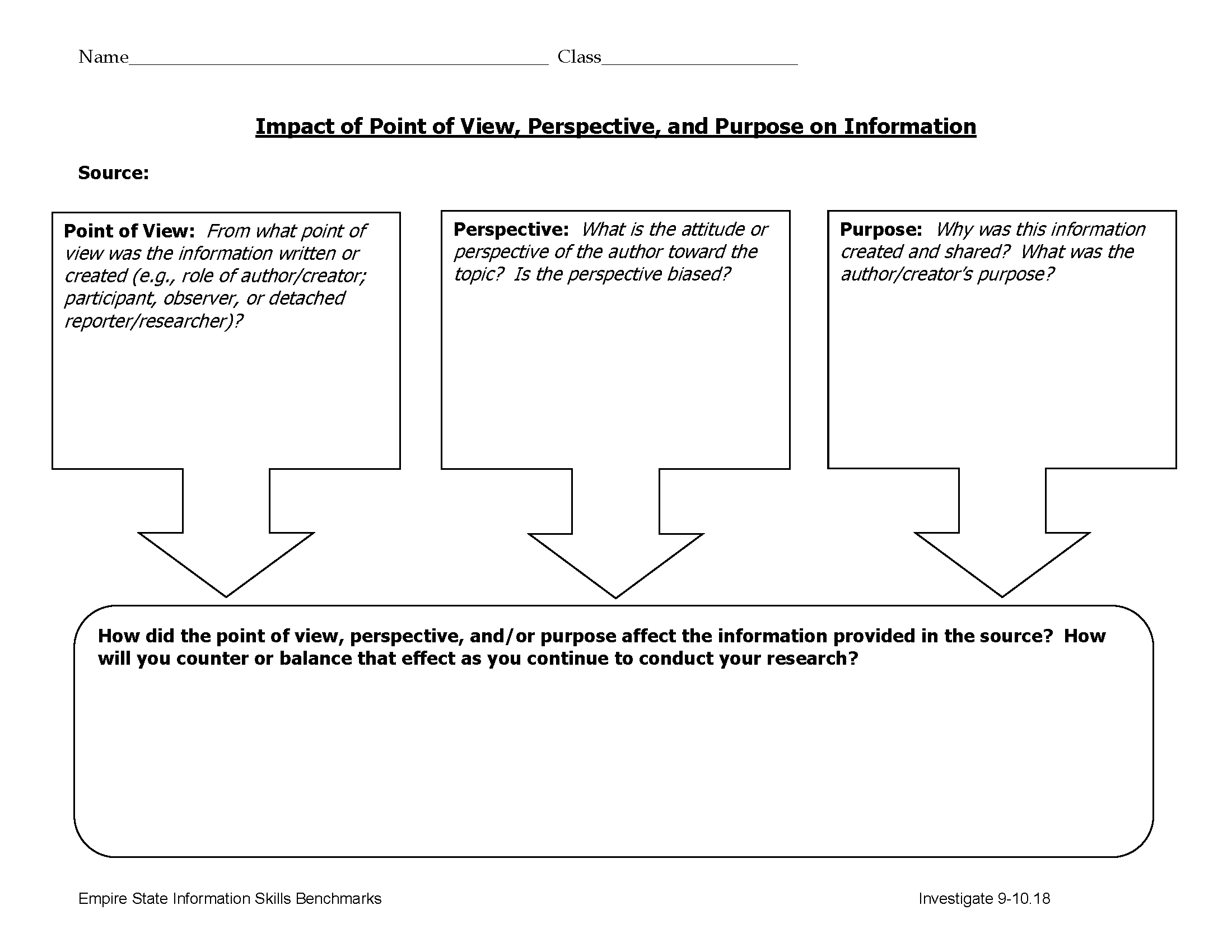

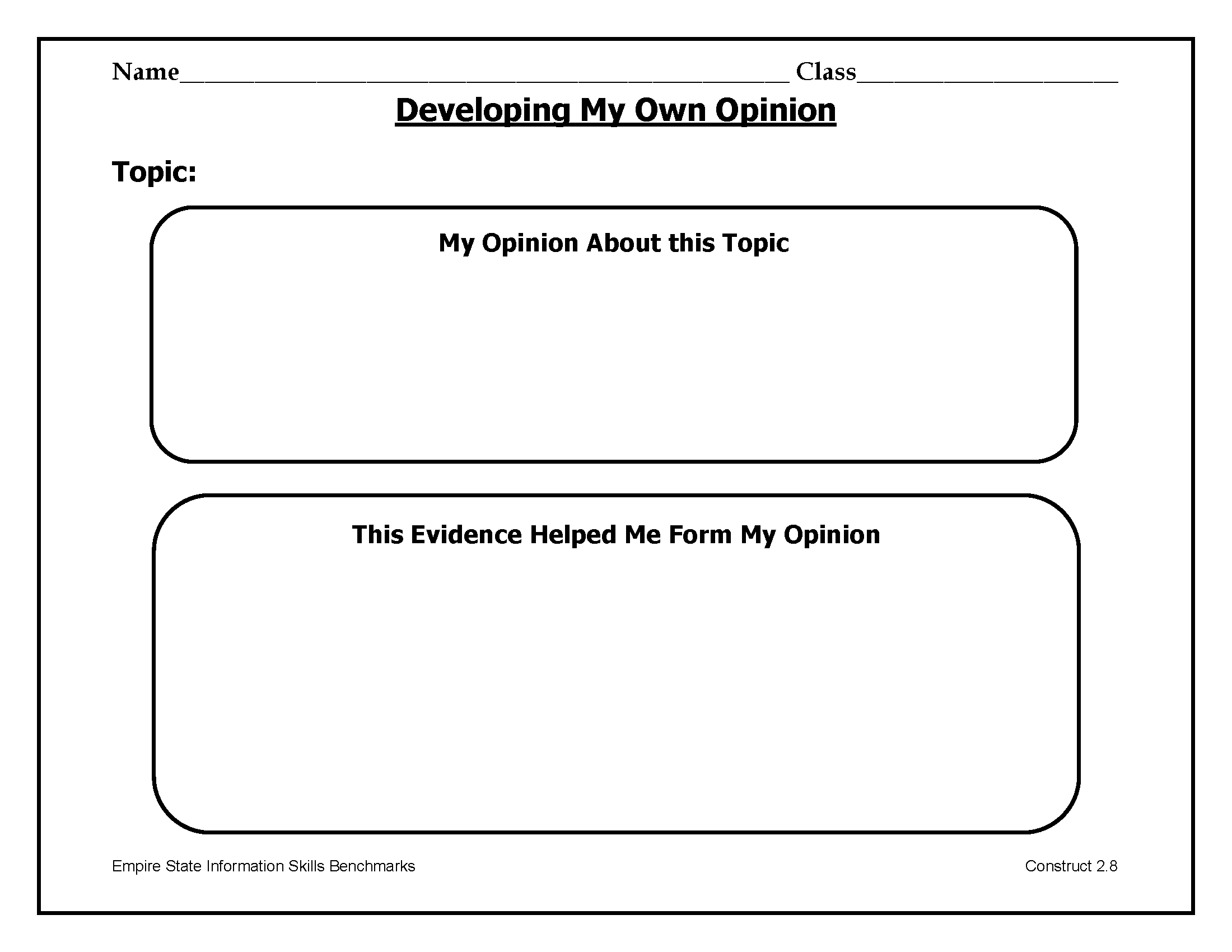

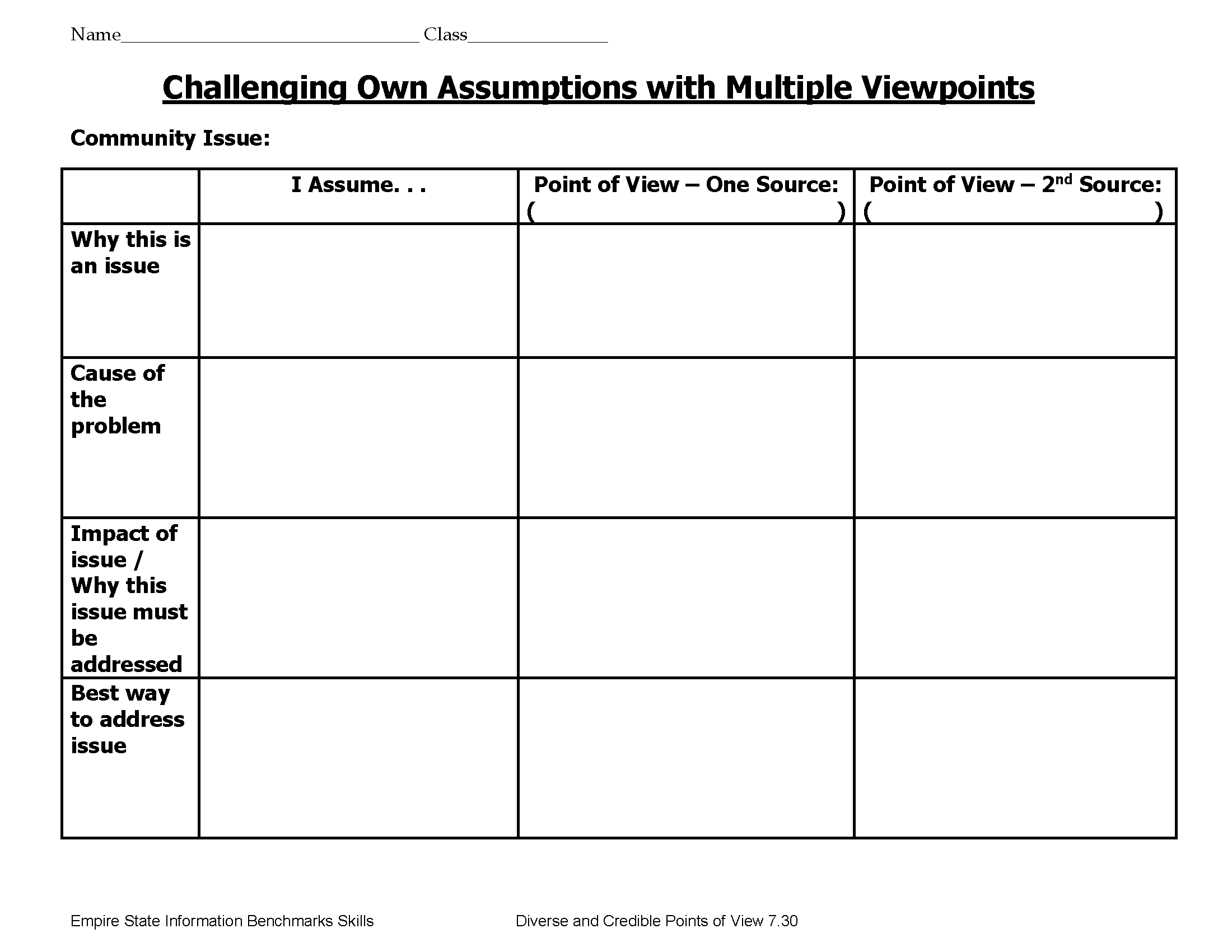

4. Deep reading. Students (and all of us, for that matter) tend to read online texts superficially. Several of you noted that you print out any document that requires deep reading and reflection; I do the same. I understand that we cannot expect our students to print out every article they encounter. There are a number of deep reading strategies that we should teach during the inquiry process, but I still have some questions about how to enable students to interact with online text, make sense of the information they find, and use that information to drive their original thinking and new understandings. I think students get a lot of value from taking notes and reflecting by hand, so I think I would forego teaching students online notetaking. Instead, I would expect students to use graphic-organizer notetaking templates that provoke their deep reading, thinking, and personal connections while they are taking notes. I would probably modify the graphic organizers to align with different formats of information (e.g., podcasts, photos, data sets). I am interested in practical strategies that others have developed to foster deep reading in the online environment.

Those are a few of the areas where we might explore in our conversation next Sunday. I look forward to meeting all of you online.

Graphic organizers (at least the ones I create and use) are different from worksheets in several important ways. First, graphic organizers are skill-based, not content-based. In other words, they are designed to guide students through the thinking process of performing a skill and to provide transparent evidence that they can perform the skill successfully. Students must think while they are working through a graphic organizer. They cannot copy their text on the organizer from any external resource; they cannot simply parrot information that someone else has already figured out. Traditional worksheets, on the other hand, often ask students to find the right, content-based “answers” in their resource or textbook and simply rewrite the answers on the worksheet.

Graphic organizers are used as a part of instruction, not as a replacement for instruction. They are used in the moment of an instructional lesson when students are ready to apply the skill on their own, after the skill has been taught, modeled, and practiced as a whole class. I think we have all had the experience of trying to learn a new skill (I think of learning new technology applications) by reading step-by-step instructions and then realizing that we haven’t really learned the skill until we try to do it. Well-designed graphic organizers provide the opportunity for students to practice the skill on their own; as an added bonus, they often offer embedded guidance and support to students through prompts, strategic visual design (e.g., Venn diagrams or mind mapping webs), reminders, and checklists. By using graphic organizers, students can independently practice applying a skill they have just been taught, but at the same time feel supported by the scaffolding built in to the organizer.

Graphic organizers are powerful tools to use for formative assessment of skill development. They allow teachers to see how well students have applied a new skill to build new knowledge and understanding. Well-designed graphic organizers will enable teachers to assess where and even why students are confused and respond either by intervening with individual students or by reteaching the skill to the whole class. In other words, graphic organizers are most useful during the process of learning so that adjustments can be made, rather than as a summative assessment to assign a grade at the end of a learning experience.

I think perhaps the main reason that I love using graphic organizers is that they allow me to see inside a learner’s mind. They allow me to join my learners on their path to new understandings. To me, graphic organizers are an effective tool for engaging with learners during a reflective inquiry journey.

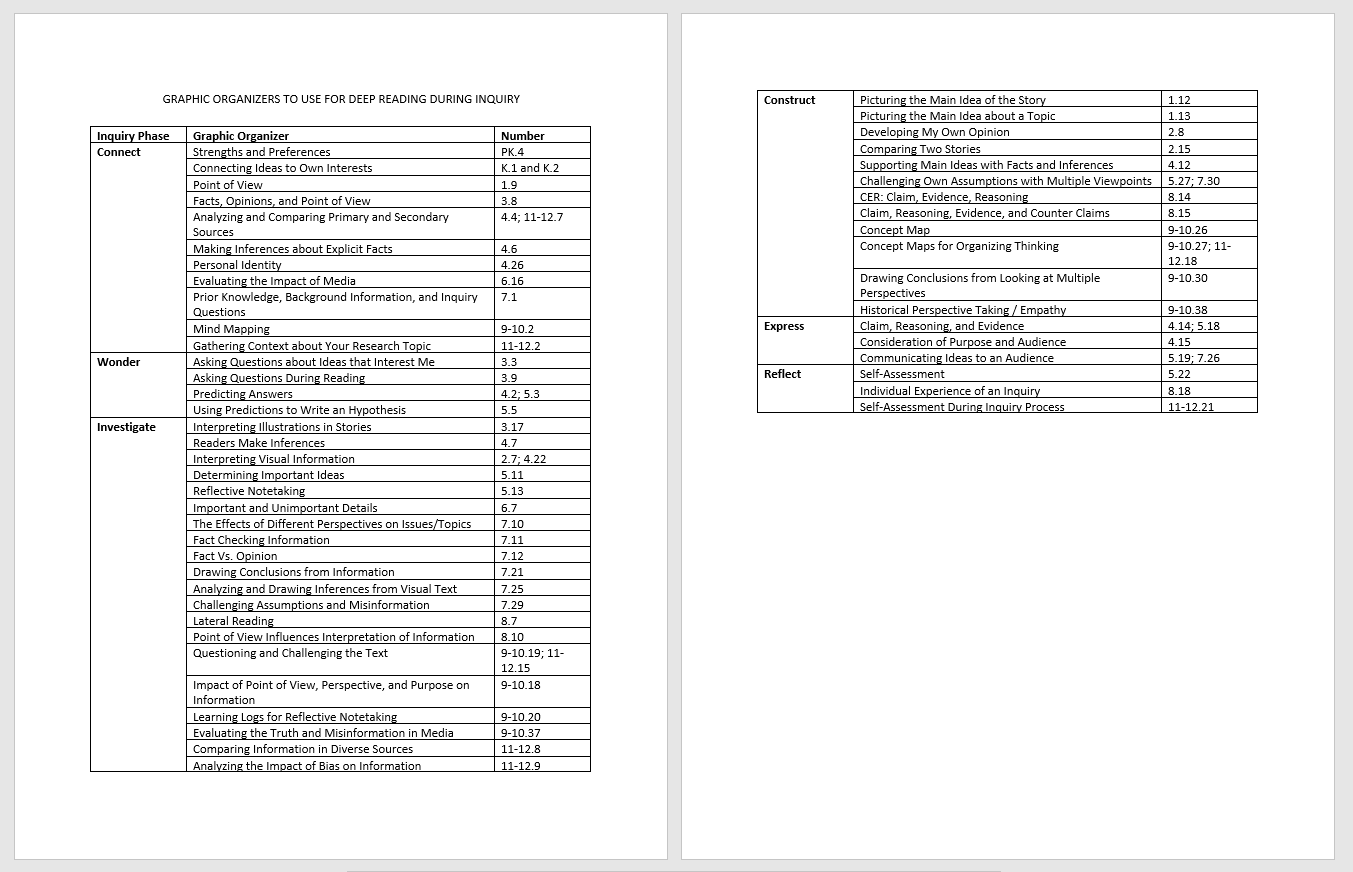

Here is a list of ESIFC graphic organizers that I think would be most appropriate for teaching the skills of deep reading (click on the image to expand it).

13th March 2021 at 1:49 am in reply to: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment #38282

13th March 2021 at 1:49 am in reply to: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment #38282I love this conversation because your insights and challenges are making me think about the practical implementation of inquiry-based learning and teaching. Although I was a classroom teacher and a building-level school librarian for over 20 years, I have been engaged at a whole-district and library-educator level for the many years after that wonderful on-the-ground experience. I tend to think large picture and ignore the day-to-day implementation.

That being said, I would like to counter your feelings of lack of preparation for the paradigm shift because you were not trained as a teacher. I regard the librarian role as a fellow learner as well as a teacher. I have learned the most about the skills I need to teach students by engaging in inquiry as a learner myself and reflecting on the process. How did I find a topic that I was passionate about? Where did I seek information? How did I make sense of the information I found? What did I do if the sources were too pedantic and complex for my taste? I actually have two topics that I have been pursuing for years, just because I’m interested in them. As I thought about my own research, I discovered several tendencies that I am ashamed to admit, but that are pretty common with students. I succumb to confirmation bias, I interpret meaning based on my own assumptions and making quick inferences from headlines and graphics, I quit looking when I cannot easily find “good” information, and on and on.

By looking at my own inquiry learning, I developed a level of comfort in my inquiry-based teaching. I could identify the skills I needed to teach. When I then went to the next step of thinking about how to teach those skills, I did rely on my teaching background briefly to structure the lesson in four phases: direct instruction, guided practice, independent practice, and sharing and reflection. But what unlocked the content of direct instruction and guided practice for me was, once again, putting myself in the learner’s role. I remember trying to develop a lesson on inference. I know how to make inferences and always used to tell students to make inferences while they read. But some students don’t know how to make inferences. I challenged myself to think through my mental process in making an inference – what were the steps I had to go through to perform the skill? I then was able to select text about a sample topic and transparently model my own thinking as I was making inferences (direct instruction). Then I guided students to think through the process as they were making inferences from a different passage of text (guided practice). I provided students with graphic organizers to lead them through the steps during independent practice. Then we came together to share inferences and reflect on what students had learned about making inferences.

I have one other comment that I think is relevant at this point in our conversation. I do not believe that the only time to teach relevant inquiry skills is when students are engaged in a full inquiry project. If we are reading a story to early elementary students, we are teaching skills of inquiry when we ask them to make predictions from the cover, or compare the feelings of two different characters, or interpret the meaning of the illustrations, or state the main idea of the story. I have been doing some learning recently about the deep reading skills that are necessary and integral for inquiry. When we know that a history teacher is preparing to cover a particular era, we can curate high-quality resources and offer to teach students one important skill as a part of that classroom work (e.g., to identify point of view, interpret visuals, or question the text to uncover the explicit and implicit meanings in those sources). My thinking is that we can start the journey toward inquiry in our schools by infusing the skills of inquiry throughout the curriculum and being transparent to the students and teachers that the skills they are learning in their classroom assignments will all come together and empower them to be successful at larger inquiry projects.

Although it may seem that we are ahead of you in implementing inquiry-based learning through our school libraries in the United States, I can assure you that we are not. We’re in this learning path together. This conversation is helping me figure out how to shift the traditional paradigm of the school librarian’s role to become the facilitator of a school-wide inquiry stance.

I recognize the importance of teaching deep reading skills as a part of inquiry, but I also know the power of enabling the development of deep reading whenever and whatever our students are reading – from stories to websites to personal explorations to inquiry. As a part my work in 2018 to develop a PK-12 information fluency continuum (adopted throughout New York State and called the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum – ESIFC) (https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc), I created a large body of graphic organizers to guide students’ independent practice for each of the priority skills in the continuum. I have selected a few that I thought would be particularly relevant to the teaching of deep reading skills. Excerpts of those graphic organizers are below, but the full, Word versions can be downloaded free from the above site. I have included the identifying numbers of the graphic organizers for your convenience.

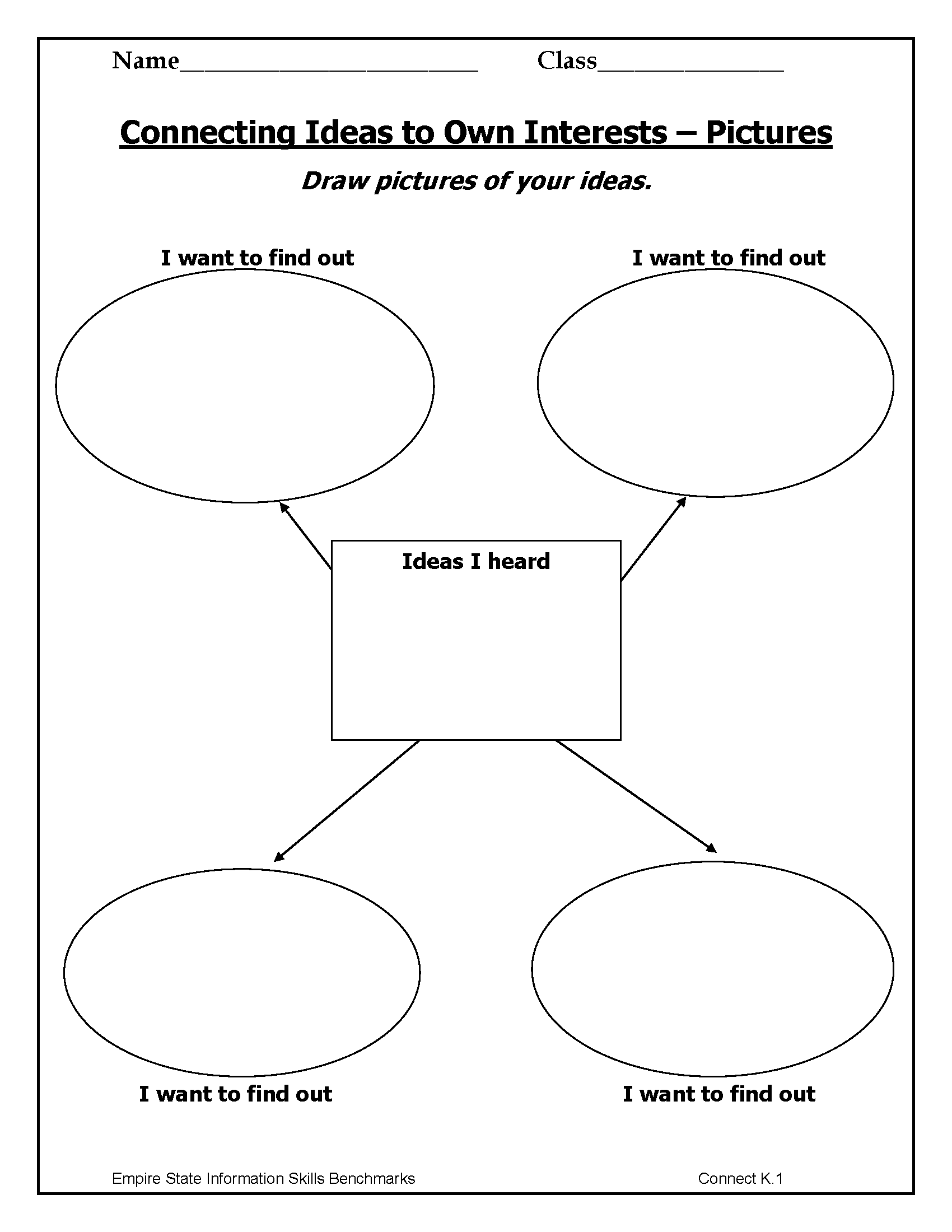

Connect. A foundation of deep reading is the reader’s ability to make connections between the text and his own interests, prior knowledge, and questions. We can start with early elementary children by enabling them to connect ideas to their own interests (K.1).

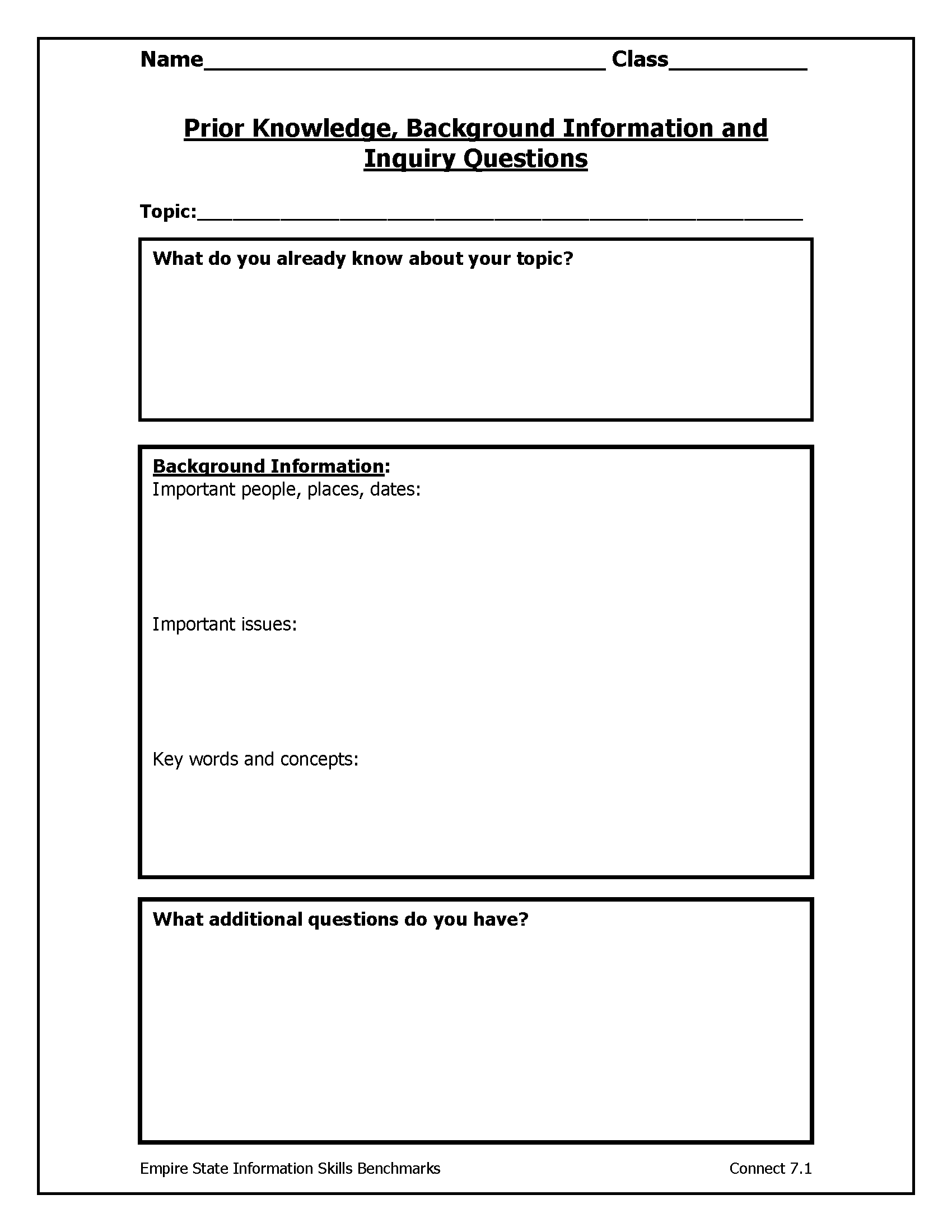

By the time students are in middle school, we can teach students to use their own prior knowledge and the background information they have gained to start asking inquiry questions (7.1).

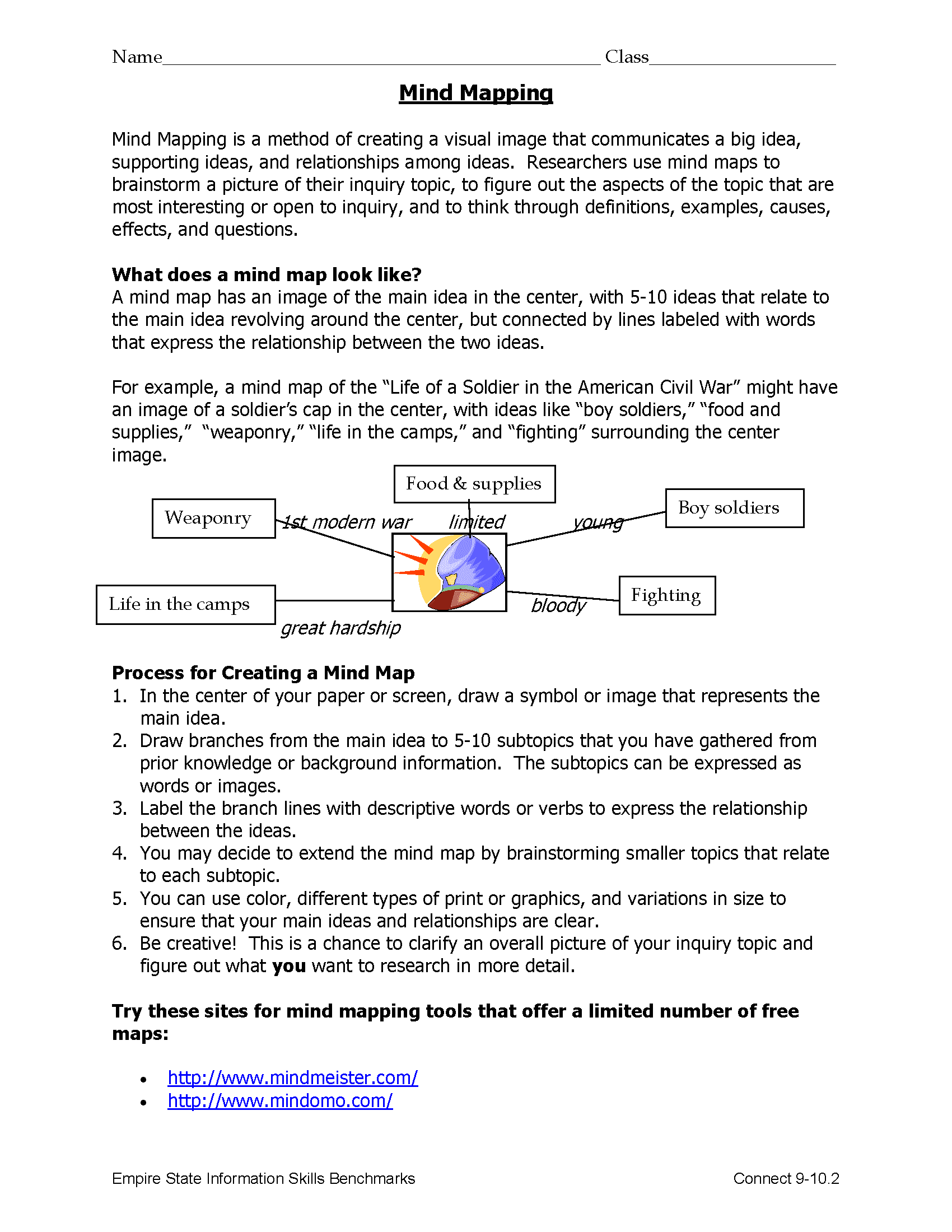

One of the important aspects of the Connect phase is for students to gain an overview picture of the whole idea, so that they can keep that context in mind when they select their focused topic for research. Librarians can develop a mind map with the whole class, with students contributing the ideas they have gained through their own reading or prior experience and the class deciding how the ideas fit together into a larger picture. Older adolescents can be taught to perform the complex reading skill of concept mapping independently (9-10.2).

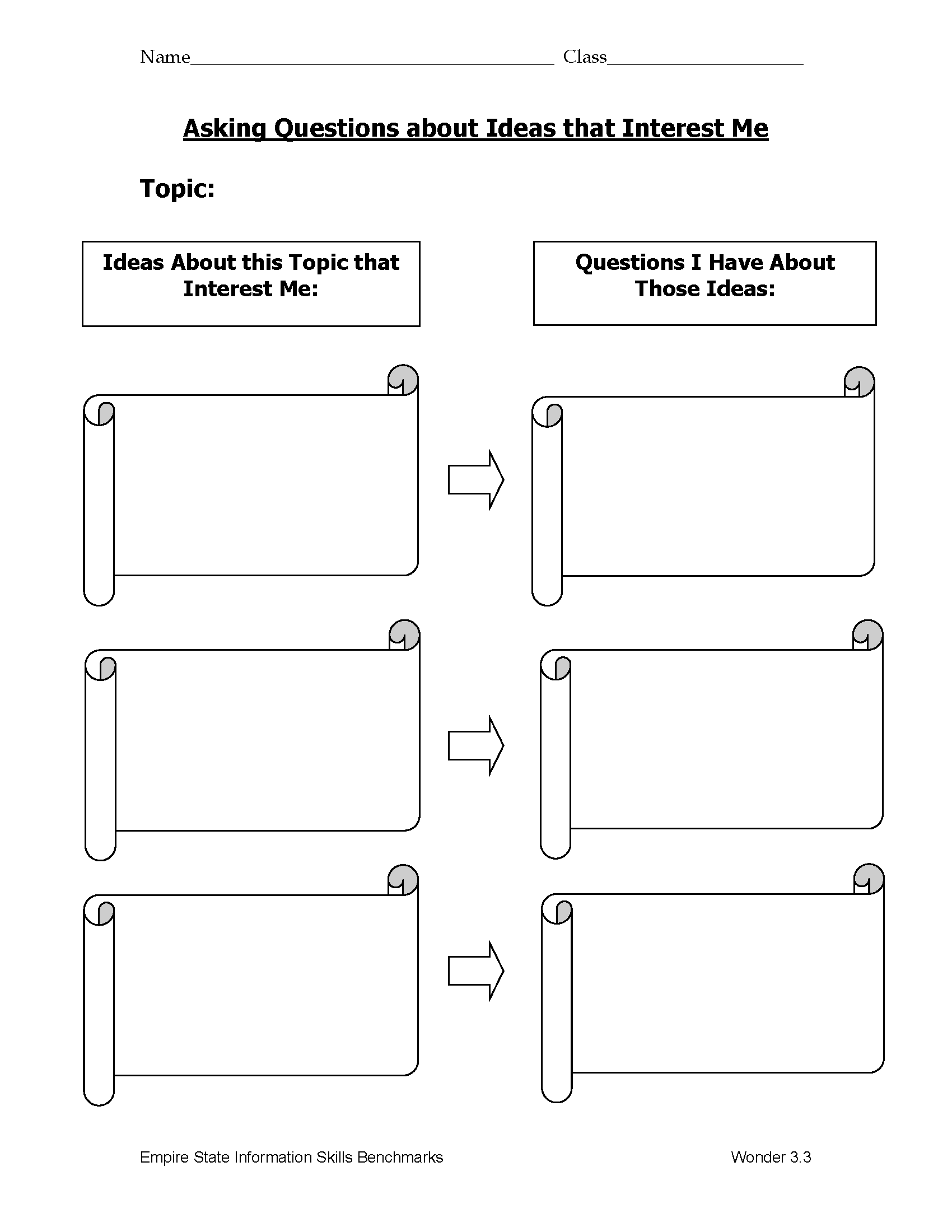

Wonder. Two of the deep reading strategies that enable students to develop Wonder questions that they are motivated to pursue are 1) to make sure that their questions emerge from a personal area of interest (3.3)

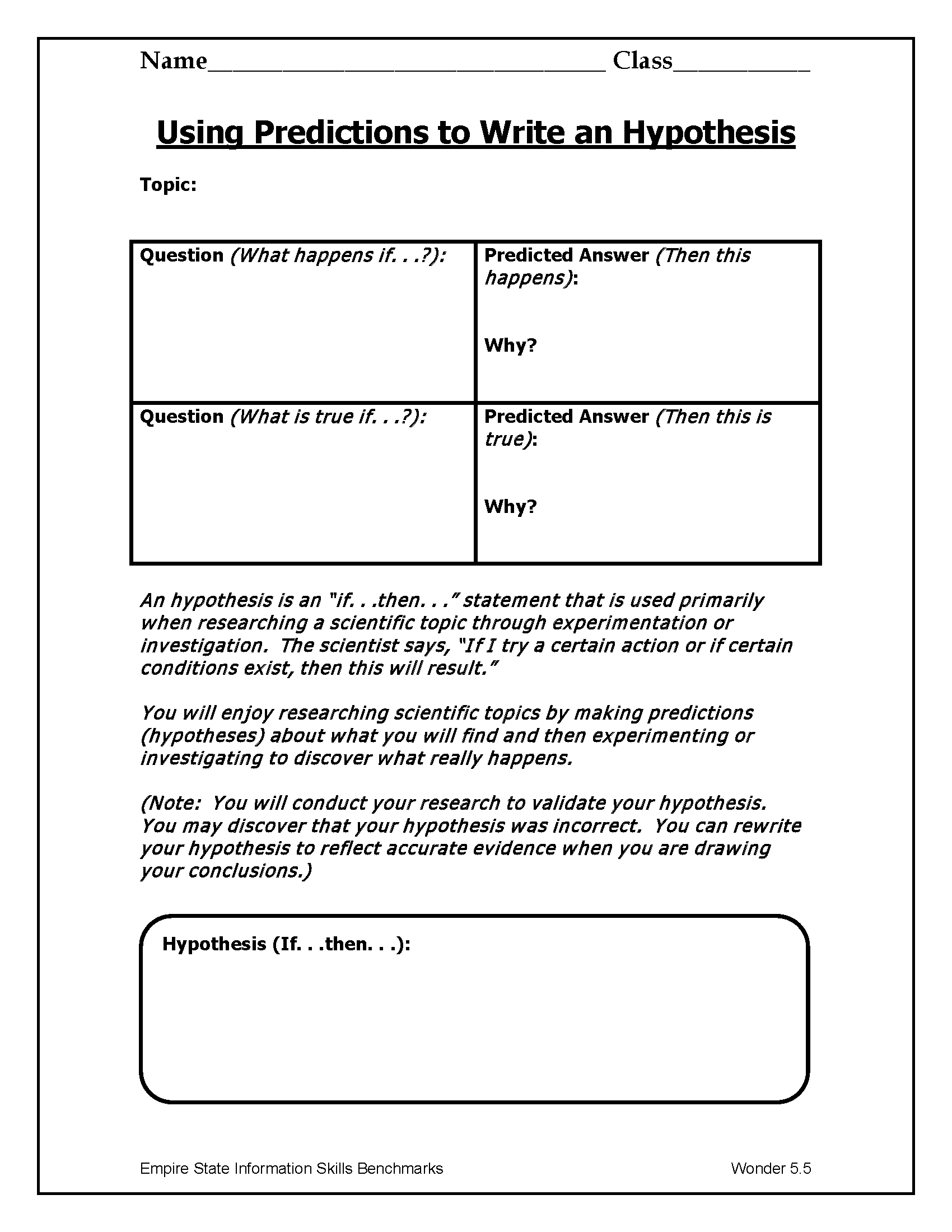

and 2) to guide them in predicting the answers they might find (and even to form an hypothesis based on their predictions) (5.5).

Reading experts have shared that, when students are personally invested and looking for answers to their questions as they read, they are more likely to read for meaning beyond simple comprehension of the text.

Investigate. Reading plays a prominent role during Investigate in any inquiry experience. The challenge for librarians is to teach students to interact with the text (in any format), to draw meaning that goes deeper than simply copying information, and to question, evaluate, and challenge the evidence they discover. The number of deep reading skills and strategies to be used during Investigate is quite large, but I have selected four skills that may not be as familiar to many librarians.

Much valuable information and alternative perspectives are offered through visualizations, including graphics, photos, art, political cartoons, and all forms of media. Students do not necessarily respond thoughtfully to visuals. Teaching that skill can start in early elementary (by drawing meaning from story book illustrations, for example) and can build in sophistication over the grades. The following graphic organizer could be to teach elementary students to interpret visual information (4.22).

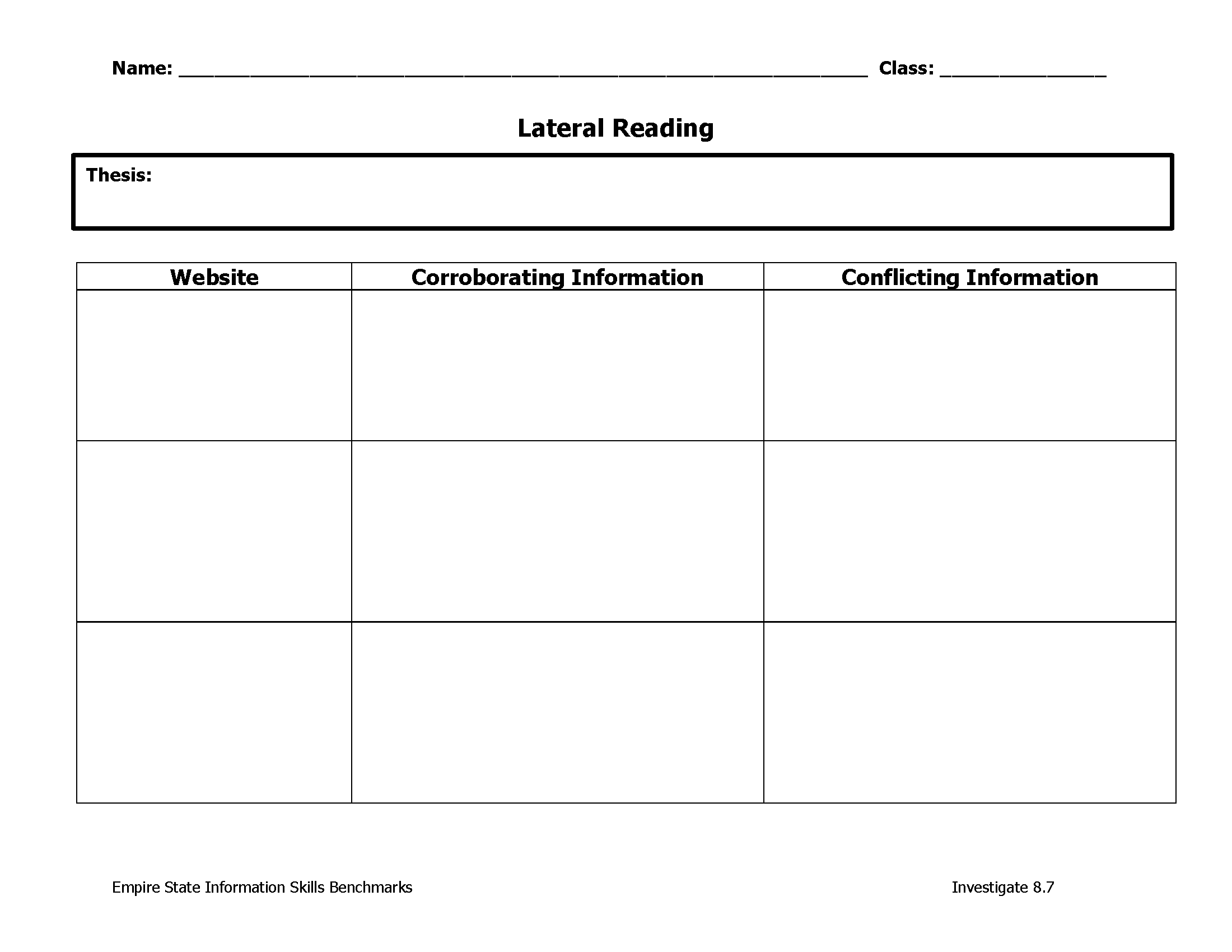

By the time students are in middle school, they should be expected to check their own inquiry process by making sure that they have been open to corroborating and conflicting information, rather than simply finding only information that confirmed their prior assumptions or their favored point of view. Teaching the strategies of lateral reading will strengthen and deepen their investigations (8.7).

An important deep reading skill, to question and challenge the text, is honestly one of the most difficult to make a permanent habit of mind, for adults as well as young people. Often the time pressures of assignment due dates will lead to cursory reading and quick fact accumulation. Expecting students to take notes in a graphic-organizer format that is designed to generate reflection and questioning is an effective way to build deep reading and thoughtfulness into investigations. The graphic organizer below is one example that librarians might use (9-10.19).

From the earliest moments in school, young people need to start identifying point of view in text that they read (or have read to them). Elementary students might start by looking at the point of view of characters in a story. These students must learn to transfer that skill to nonfiction texts during their inquiry investigations. By the time that students are in secondary school, they can be taught to assess the impact of point of view, perspective, and purpose on the information itself (9-10.18).

Construct. Although students may not be reading any new texts during the Construct phase when they are developing their own opinions and conclusions, they are re-reading their notes and perhaps sections of the sources they found most critical to their investigations. Reflective reading at this stage involves synthesizing the evidence they have discovered with the thoughts, opinions, feelings, and meanings that they have formed in response to the evidence.

When I first started focusing on inquiry, both as a stance and as a process for learning, I remember simply telling my students to draw their own conclusions after they had found the information they needed. When I saw my students struggling, I realized that the deep reading and inquiry skills of Construct must be taught explicitly. Students may be able to form opinions naturally, but those are not opinions based on careful assessment of the evidence. I had to teach students how to construct their own ideas and understandings based on their investigations and their careful analysis.

Young students can be taught to form their own opinions in early elementary. The essential piece is that they must tie their opinions to the evidence they have heard or discovered (2.8).

By the time students are in middle school, they should be expected to identify their own assumptions and challenge them by considering multiple viewpoints (7.30). Direct instruction on how to identify the viewpoint or perspective of a text, plus graphic organizers to guide them through the analysis process, will enable students to construct their own understandings based on evidence.

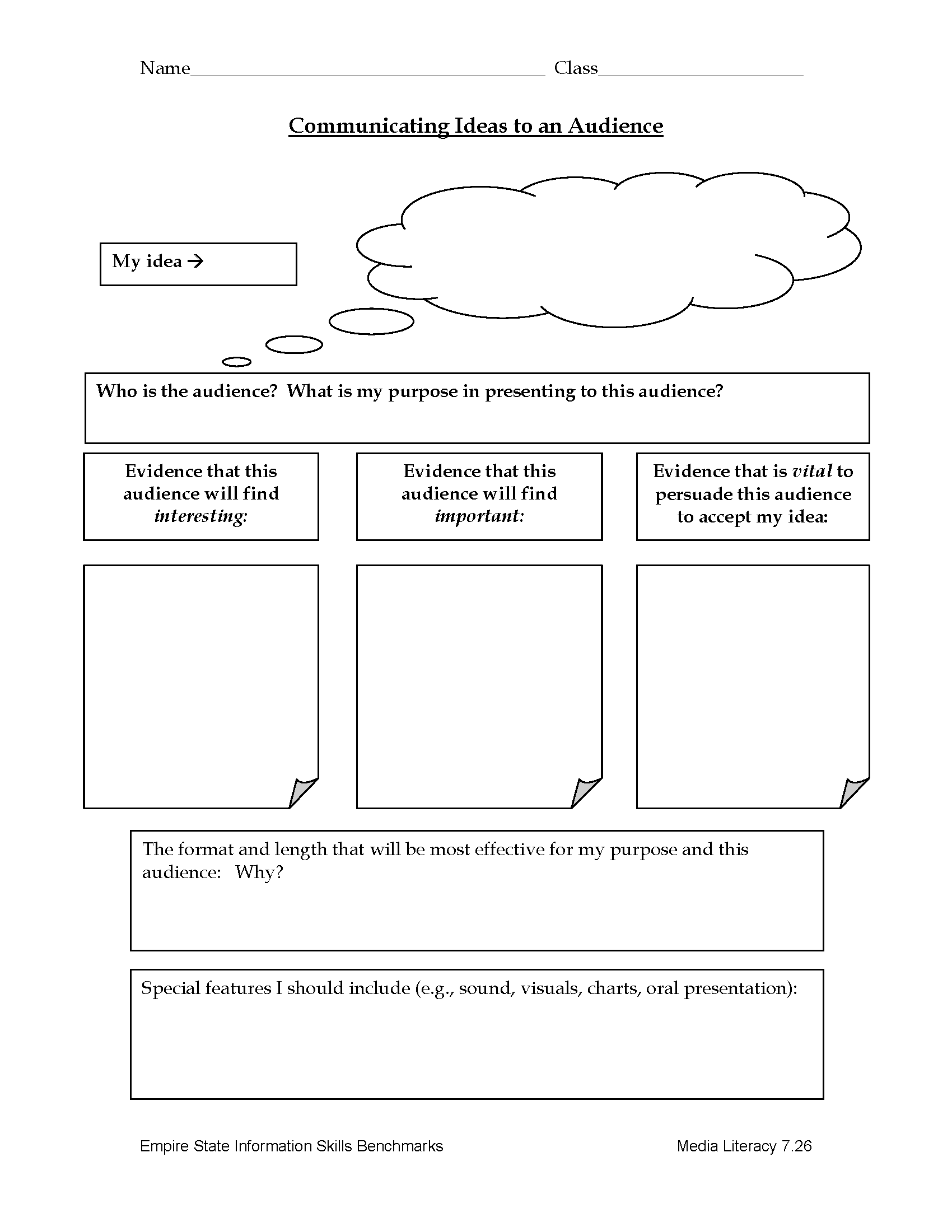

Express. A broad interpretation of deep reading skills at the Express phase includes teaching students to use language and other communication tools to create and share expressions of their new understandings. As leaders of inquiry for the whole school, librarians are in an excellent position to assume responsibility for teaching students the creation and presentation skills that will be relevant whenever they have the opportunity to share their learning. One communication skill that is rarely taught is “reading” an audience and tailoring a presentation to appeal to that audience (7.26).

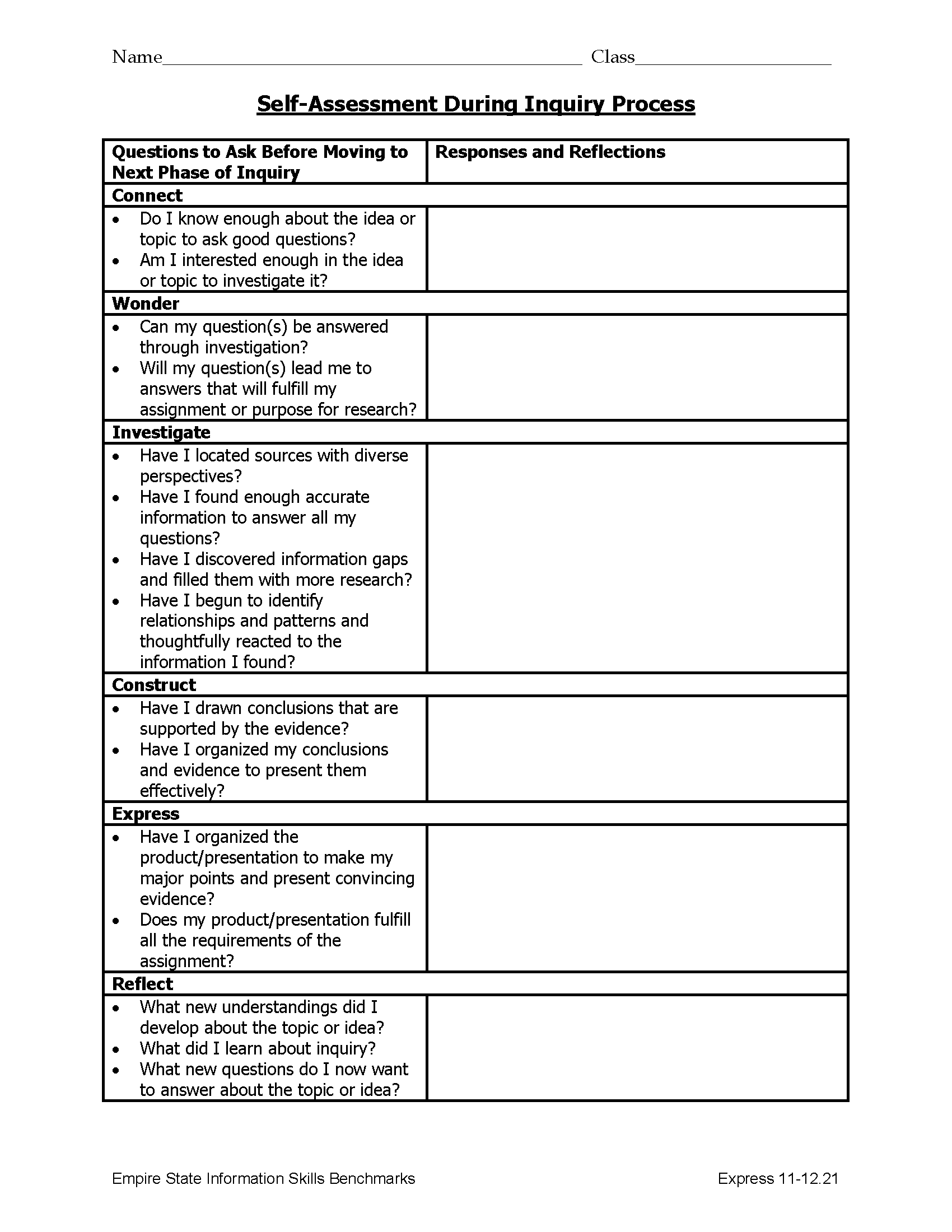

Reflect. Although reflection is built in to every phase of the inquiry process, the value in reflecting on the entire process and product at the conclusion of the inquiry experience is that it enables the learner to move from a look at one experience of inquiry to a broader perspective on inquiry as a process and a stance on learning. The concluding reflection allows the learner to self-assess and to be in charge of setting personal goals for improvement. The first template below offers questions for the learner to ask himself throughout the process of inquiry (11-12.21).

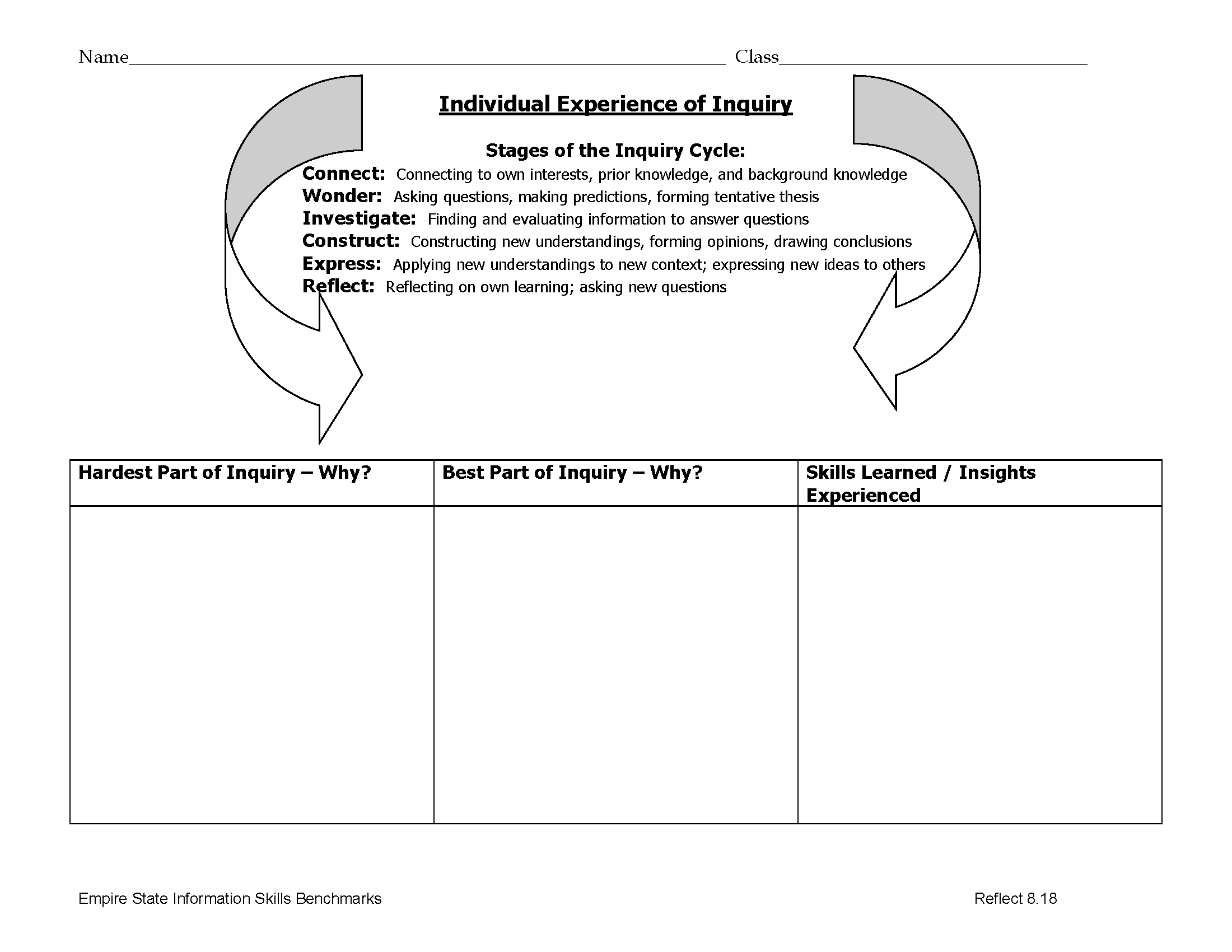

Students at every grade level can be asked to think about their individual experience of inquiry. The graphic organizer below can be adapted for any grade level (8.18).

Half of the fun of using graphic organizers in order to guide students during their independent practice is designing organizers that enable students to be transparent in their thinking while they are performing a skill. Librarians can use these formative assessments to discover when students are struggling and perhaps even where their confusions lie. Students have a sense of completion and success when they have been able to successfully follow the thinking process inherent in the deep reading and inquiry skills we are teaching.

I am very interested in this conversation about inquiry at the elementary level. I do think it’s important to help students, even at the primary level, understand the underlying process. I would, of course, teach it through an appropriate real-life example, like the process of choosing a pet. I agree that students can handle the names of the phases when they actually understand what it means to Connect or Construct. The way that inquiry is implemented in elementary school, especially the primary grades, is by necessity quite different from the upper grades where the librarian has more time with the students and many more opportunities to work with teachers on designing full inquiry experiences.

I have thought of a couple of ways that I would approach the challenge of implementing inquiry in the elementary grades. First, I would decide the priority skills that I wanted to teach for each grade in order to focus and limit the number of skills I planned to teach. That is why the ESIFC has explicitly highlighted priority skills. In consultation with your teachers, you can decide what inquiry skills are most important for the students at your school. Priority skills will certainly include thinking skills, but also probably include social and emotional competencies, like being able to identify personal interests and feelings. Inquiry is propelled when students are motivated by their own experiences and personal connections.

These skills can be taught separately from a full inquiry experience. I think a powerful way to teach them to younger students is through picture books and stories. If we want students to be able to tell the difference between fact and opinion, for example, we might read a story with both and talk through the criteria to tell the difference as we identify both facts and opinions in the story. I would be explicit with the students that they are learning how to be inquirers even while we are reading stories together. I would use graphic organizers to give students a chance to practice differentiating between fact and opinion (and to give me a chance to assess their success at learning the skill).

When we do have a chance to guide students through an entire inquiry experience, we can expect students to use the skills they have already learned (with support as needed) and scaffold the skills we have not yet taught (like providing the best sources for students to use, rather than expecting them to select their own resources for this project).

I feel comfortable at this cumulative approach to inquiry because I would have developed a continuum of priority skills with the teachers at my school. We would all know what we need to teach for students to develop as inquirers and we would have the comfort of knowing that the important skills will build over time.

I am very interested in your further thoughts about implementing inquiry at the elementary level.

4th March 2021 at 5:07 pm in reply to: Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment #37491I agree with you, Elizabeth, that we, as librarians, need to offer more than simply teaching traditional research skills. If we accept the “paradigm” that inquiry is a way of learning, a stance that guides one’s interaction with the world (in school and beyond), then librarians must engage with the whole child, not just the academic or cognitive side.

I have been trying to understand what it means to “engage with the whole child.” Instinctively, I knew that social and emotional skills were a part of learning, but I have been pursuing my own inquiry into the SEL realm. I have been investigating the blend of social and emotional skills and attitudes with the cognitive skills of inquiry. That idea speaks to your point about understanding what students bring to the inquiry – they need to know who they are, what prior knowledge and experiences will inform their new learning, what assumptions and attitudes (feelings) they hold that will affect their interpretation of new information, what interests them about the topic, and so on. An inquiry stance demands mindfulness, an understanding of everything the learner brings to the table, including past experiences, feelings, knowledge, questions, interests, and passions.

I believe that we can enable our students to become mindful learners by guiding them through a reflective process of inquiry. Our students need to think about what and how they are learning throughout the process. To guide them, we need to transform our pedagogy to a more constructivist approach that enables students to construct new understandings on their own, applying the skills and strategies that we teach. For me, then, the paradigm shift for librarians includes both our understanding of what we need to teach, but also how we need to teach. I think we need to adopt an inquiry stance on librarianship.

I have been reflecting lately on the role of reading, and more broadly literacy, in enabling learners to make sense of themselves and the world. The superficial type of reading fostered by the digital environment and the preponderance of misinformation and even disinformation have put me on high alert. I am worried about the tendency of both adults and young people to dart from one site or source to another, processing little beyond graphics and headlines, ignoring any text that is too complex or challenging, and believing anything they “read.” If my goal is to enable students to become independent learners with an inquiry stance on the world, then it is my responsibility to integrate the teaching of deep reading skills into my teaching of inquiry.

To provoke my own thinking, I recently read Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World by Maryanne Wolf. Although Wolf’s focus is reading, I engaged with the book through my lens of inquiry. I tried to translate Wolf’s ideas about digital reading into the types of reading and the skills that I thought would be most important at each phase of inquiry. It’s been an interesting process. I have certainly deepened my understanding of the skills that students need to be able to develop their own ideas, interpretations, and conclusions throughout the process of inquiry. I share my thoughts below in the hope that others will push back, question, and add to my ideas about integrating deep reading with inquiry.

Connect. The Connect phase of inquiry has probably been impacted more than any other phase by my new understanding of deep reading skills. Originally, I envisioned students engaged in overview activities, like listing what they think they already know about the topic and gathering background knowledge of the main ideas, people, dates of the overall topic. In my mind, Connect was largely an intellectual experience. By adding deep reading strategies, Connect can be transformed into a highly personal, relevant, and meaningful start to an inquiry experience. I would teach students to identify their own feelings and assumptions about the topic, read laterally to discover multiple perspectives, determine the importance of information, create a conceptual map of major ideas and overall context, and discover aspects of the topic that are personally interesting or evocative.

Wonder. Wonder questions are usually generated from the internal and external connections that students make during the Connect phase. Teaching the strategy of questioning the text will facilitate the development of questions that students are motivated to pursue through inquiry: challenging the ideas in text (Why?, What if?, So what?); extending the ideas in text (What else is important?, Whose voices are missing?); and connecting to their own personal interests (Why do I care about this?, What intrigues me?).

Investigate. An important reading strategy to enable students to pursue deep meaning and not just bits of information during their investigations is interactive reading. Two-column notetaking provides a template for students to think about the information they are noting and respond in the right column with questions, challenges, opinions, and emotional reactions. Many students find their investigations challenging because they lose focus, get frustrated, or get overwhelmed. We can teach reading self-management skills to help students overcome their challenges: maintaining focus by setting a daily limited learning target, using question-based notetaking strategies, continuous self-monitoring of comprehension and interpretation; and maintaining a research log of reflections on their progress. Wolf reminded me that both deep reading and inquiry require “cognitive patience,” or the time, persistence, and open mind to think deeply and let new ideas percolate.

Construct. Students should be engaged in reflective reading during Construct to facilitate combining their internal knowledge (experiences, feelings, interpretations) with their external knowledge (information they have acquired during their investigation, their responses to that information) to form new understandings. Several skills of reflective reading are particularly valuable for students during Construct: perspective taking (empathy), or understanding another’s perspectives, feelings, and actions; challenging their own thinking by questioning their own interpretations and conclusions; and what Wolf calls “reading for the narrative,” or looking for the conceptual whole that brings all of the new ideas together into a new understanding that makes sense.

Express. Imagination is an important component of deep reading that is essential during the Express phase. Students can use creative thinking to envision, develop, and present expressions of their learning that convey multiple layers of meaning – new understandings and the supporting evidence, personal interpretations and conclusions, and the personal passions and self-confidence that developed during the whole inquiry experience.

Reflect. The deep reading strategy of reflection should permeate the entire inquiry experience, but the final reflection presents the opportunity for students to solidify their inquiry stance. When students reflect on their inquiry process and product, they recognize their own strengths and challenges in engaging in academic and personal learning. They develop agency and self-confidence to adopt an inquiry stance as a way of interacting with the world.

I recognize that this reflection on the power of integrating deep reading strategies into inquiry is aspirational. I am thinking about the vision I want to achieve for all our students. Now, we must all engage in the hard work of figuring out how to bring this vision to life in our schools.

Wolf, Maryanne. Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. NY: Harper, 2018.

-

AuthorPosts