Article | ALISS Quarterly

Tags: ArticleAugust 1, 2023

The first published article about FOSIL – Not Waving but Drowning: Reconsidering Transitions at Oakham School – was written by Darryl Toerien for ALISS Quarterly (Volume 9, Number 3, April 2014), the journal of the Association of Librarians and Information Professionals in the Social Sciences.

Almost exactly 10 years later Darryl was invited by the Editor to write a reflection on the extraordinary developments of and around FOSIL since then, which are ongoing.

The article is shared here with permission from the Editor.

—

Rethinking the Idea of a School Library As Integral to the Educational Process

If history is the consequence of ideas (Ellul, 1989), then the idea of the school library as integral to the educational process, and by extension to school, seemingly has long lost its power to produce a history of school libraries in which this turns out to actually be the case. This, then, makes a history of schools without school libraries increasingly likely, even as the catastrophic consequences of this history become ever clearer. The reasons for this historical development are many and varied, and need to be uncovered for the record, but the pressing questions that remain before us are whether or not it is too late to reimbue this idea with enough power to change history, and whether or not we are willing to make the effort on behalf of those who depend on us to do so?

I was kindly invited by the Editor to revisit an article that I wrote for a Special Issue of ALISS Quarterly (Volume 9, No. 3, April 2014) – Supporting staff and student development: Transitions – which was titled, Not Waving but Drowning: Reconsidering Transitions at Oakham School (Toerien, 2014). The reason for revisiting the original article is that it was the first article that I wrote about FOSIL, and the current article effectively marks 10 years of intense development of FOSIL as a means through which the school library becomes integral to the educational process. It is fitting, then, that as I write this article, Blanchelande College – where I was appointed as Head of Inquiry-Based Learning in 2021, which is 10 years since I first conceived of FOSIL – has been shortlisted for the UK School Library Association Enterprise of the Year Award, given that this very idea is the focus of our submission.

FOSIL stands for Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning, although in 2014 I understood it as Framework for Oakham School Information Literacy (for more on the naming of FOSIL, which is isn’t just an acronym, see here, and for a brief history, see here). This shift in instructional focus is significant, and it mirrors a global shift from information literacy to the development of information literacy skills within an inquiry process, a shift that is reflected in the first edition of the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2002) and the second edition (2015). Curiously, this shift is not reflected in UK professional guidelines – for example, in the second edition of The CILIP Guidelines for Secondary School Libraries (2004) and the third edition (2014), even though the UK was represented on the Standing Committee of the IFLA School Libraries Section during this period – which is a historical curiosity with far-reaching consequences. One of these consequences is that inquiry is poorly understood in the UK and, therefore, often confused with information literacy, with the main difference here being that inquiry is a learning stance and process that (1) is directed towards acquiring important subject content, and (2) draws on a range of learning skills, some of which are information literacy skills.

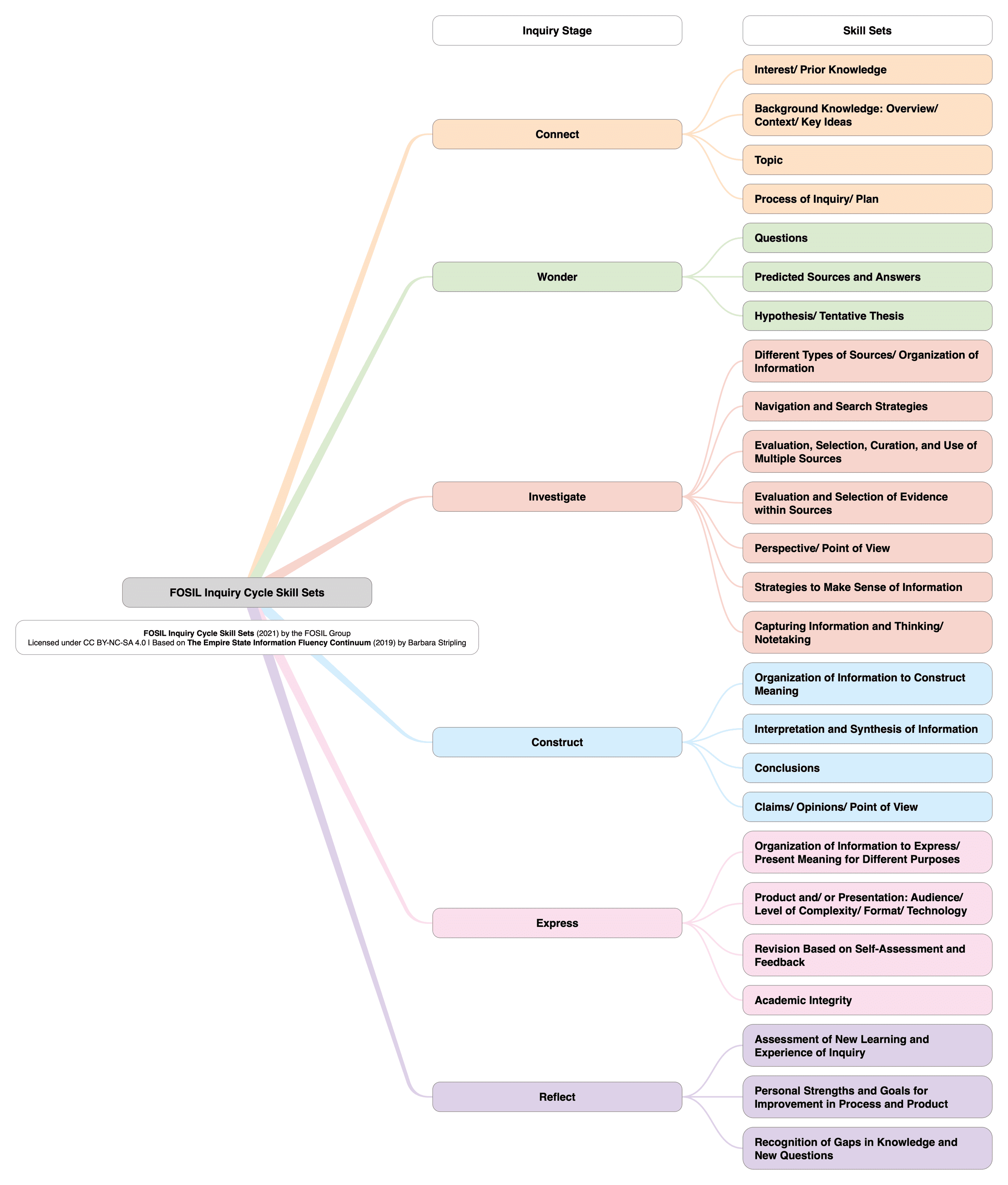

FOSIL (2011) is an instructional model of the inquiry process that is based on the work of Barbara Stripling, Professor Emerita at Syracuse University, as reflected in the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (2009 & 2019, although Barbara developed the instructional model in 2003). The ESIFC/ FOSIL is then also a framework of inquiry skills – metacognitive, cognitive, emotional, social and cultural, with many being technology-dependent by definition or in use – that enable each stage in the inquiry process, and that are developed systematically and progressively from PK-12 (Reception-Year 13) within the context of subject area learning and teaching. Figure 1 below shows the FOSIL Inquiry Cycle stages and skill sets – for the PK-12 framework of skills, see here.

Figure 1: FOSIL Inquiry Cycle and Skill Sets

The ESIFC is endorsed by the New York State Education Department, which serves more than 3.2 million students across 4,236 schools, and has been widely adopted/ adapted within and beyond the US. In April 2020, FOSIL was commended by Barbara in email correspondence with the author for its “clear and elegant presentation of inquiry,” and we have since developed a deep and lasting collaboration on the co-evolution of the ESIFC/ FOSIL. Fruit of this collaboration is evident in, for example, the publication in 2022 of Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (Schultz-Jones & Oberg), with the ESIFC and FOSIL accounting for two of the five models selected for the book: The Stripling Model of Inquiry (Stripling B. K., 2022) and FOSIL: Developing and Extending the Stripling Model of Inquiry (Toerien, 2022). Moreover, FOSIL is the only major model where ongoing development is being led from within a school rather than a university or as a commercial enterprise. This, and the fact that our work is freely available under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, accounts in large part for the growing popularity of FOSIL around the world, particularly in Australia, where it has become the model of choice for students on the Master of Education in Teacher Librarianship programme at Charles Sturt University. To support the adoption/ adaption of FOSIL, we established the FOSIL Group in 2019, which is an international community of educators who frame learning through inquiry, and whose growing membership represents well over 30 countries at the time of writing. There are 864 Forum posts across 203 Topics, with 87 FOSIL-based Resources freely available to download. Since my first article on FOSIL in April 2014 and this one, I have written at least 40 FOSIL-related pieces for publication, varying in length from a blog post to a book chapter (some of which are available here), with a book in the pipeline, and made at least 60 FOSIL-related presentations (some of which are available here).

Why?

I return to Neil Postman (1996, p. x), who argued that “non-trivial schooling can provide a point of view from which what is can be seen clearly, what was as a living present, and what will be as filled with possibility”. Inquiry – understood as “a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in society” (Stripling & Toerien, 2021) – is fundamental to non-trivial schooling. This is why Postman further argued that of all the survival strategies that education has to offer, none is more potent than inquiry or in greater need of explication (1971), provided that we avoid the tendencies that sap inquiry of its educational potency (1979), which is the focus of an extended workshop that I have been invited to co-lead at the IASL Conference in Rome (17-21 July 2023). Briefly, these tendencies are:

- to divorce inquiry as a dynamic process and skills from learning important content;

- to reduce inquiry to a mechanical process by divorcing it from a spirit of wonder and puzzlement;

- to divorce inquiry from both a spirit of wonder and puzzlement and a dynamic process, and so reduce it to a thoughtless fact-finding activity;

- to “engineer learning” through ever-more technical teaching methods based on ‘hard evidence’ from the field of cognitive science.

That our children are in desperate need of a potent survival strategy is painfully clear from even a passing glance at any given day’s news. The complex existential crisis that threatens to overwhelm them is of our making and is epistemological in nature, a consequence of the breakdown of the knowledge-building process, which is an inquiry process, resulting in an inability to see clearly “what is” and so be able to deal appropriately with reality (Toerien, 2024). By contrast, the ability to see clearly “what is” and so be able to deal appropriately with reality has been the hallmark of an educated person since ancient times (Willard, 1999), although why and how this changed is beyond the scope of this article. Perversely, our own trivial schooling makes it all the less likely that we will be able to provide our children with a non-trivial one, thereby failing them a second time. However, library-led resistance to trivial schooling is not yet futile, as our submission for the SLA Enterprise of the Year Award demonstrates (see here).

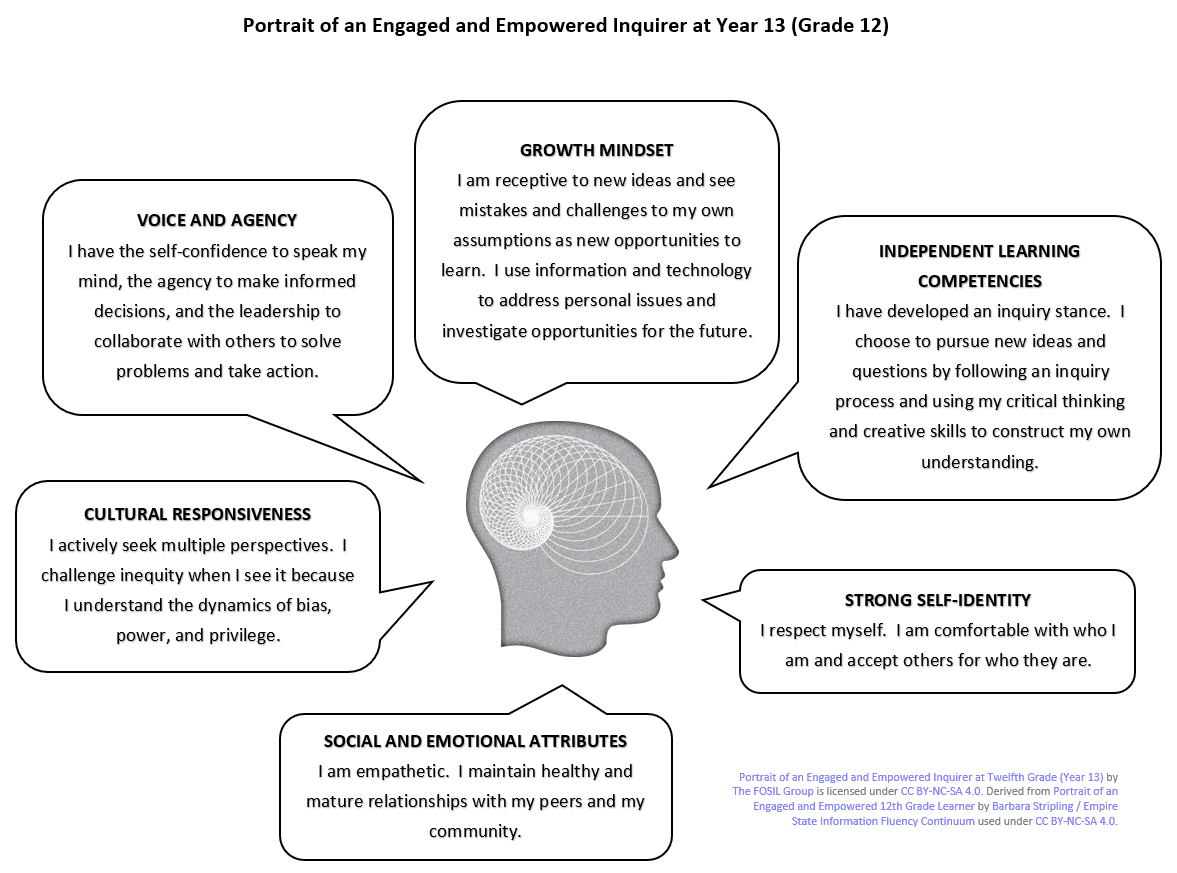

I end with our portrait of an engaged and empowered inquirer at Year 13 (see Figure 2 below), which represents a student who emerges from their non-trivial schooling both willing and able to strengthen the reality-based community of error-seeking inquirers upon which liberal democracy depends (Rauch, 2021). Inquiry has this as its end and is the means to this end, and Charles Sanders Peirce (1955, p. 54) powerfully frames this educational imperative:

Upon this first, and in one sense this sole, rule of reason – that in order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so desiring not be satisfied with what you already incline to think – there follows one corollary which itself deserves to be inscribed upon every wall of the city of philosophy: Do not block the way of inquiry.

The revolution will not be televised.

Figure 2: Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Grade 12 (Year 13)

—

Bibliography

- CILIP School Libraries Group. (2004). The CILIP Guidelines for Secondary School Libraries (2nd ed.). London: Facet Publishing.

- CILIP School Libraries Group. (2014). The CILIP Guidelines for Secondary School Libraries (3rd ed.). London: Facet Publishing.

- Ellul, J. (1989). The Presence of the Kingdom. Colorado Springs: Helmers & Howard.

- IFLA School Libraries Section. (2002). IFLA/UNESCO School Library Guidelines (1st ed.). The Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions.

- IFLA School Libraries Section. (2015). IFLA School Library Guidelines (2nd ed.). The Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions.

- Peirce, C. S. (1955). The Scientific Attitude and Fallibilism. In J. Buchler (Ed.), Philosophical Writings of Peirce (pp. 42-59). New York, NY: Dover Publications.

- Postman, N. (1979). Teaching as a Conserving Activity. New York, NY: Delta.

- Postman, N. (1996). The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. New York, NY: Random House.

- Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. (1971). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Rauch, J. (2021). The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defence of Truth. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Schultz-Jones, B. A., & Oberg, D. (Eds.). (2022). Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry.Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

- Stripling, B. K. (2022). The Stripling Model of Inquiry. In B. A. Schultz-Jones, & D. Oberg (Eds.), Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (pp. 48-61). Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

- Stripling, B. K., & Toerien, D. (2021). Inquiry: An Educational and Moral Imperative. School Library Association Weekend Course: Leading School Libraries: Library, School, Sector. School Library Association (UK). Retrieved from https://fosil.org.uk/forums/topic/sla-2021-inquiry-an-educational-and-moral-imperative/

- Toerien, D. (2014). Not Waving but Drowning: Reconsidering Transitions at Oakham School. ALISS Quarterly, 9(3), 12-15.

- Toerien, D. (2022). FOSIL: Developing and Extending the Stripling Model of Inquiry. In B. A. Schultz-Jones, & D. Oberg (Eds.), Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (pp. 62-76). Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

- Toerien, D. (2024). Digital Literacy: Necessary but Not Sufficient for Life-Wide and Life-Long Learning. In J. Schmidt (Ed.), Libraries Empowering Society through Digital Literacy Education. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

- Willard, D. (1999). The Unhinging of the American Mind – Derrida as Pretext. In B. Smith, European Philosophy and the American Academy (pp. 3-20). Chicago: Open Court Publishers. Retrieved from https://dwillard.org/articles/unhinging-of-the-american-mind-derrida-as-pretext-the

Login | Register or fill out the form below to comment as a guest