ChatGPT et al

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › ChatGPT et al

- This topic has 29 replies, 6 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 1 month ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

1st March 2023 at 8:57 am #79732

A discussion about ChatGPT in particular – given the news and the hype – and AI more generally is overdue.

My apologies to Matt, who attempted to get the discussion going a while ago, but ran into technical difficulties on our end – I am hopeful that this has been resolved and that he will add his thoughts here soon.

I have so far lacked time to gather my thoughts, but as I am starting to work on our academic integrity policy, which will include the development of digital and MIL (media and information literacy) skills within an inquiry learning process, the time has come.

1st March 2023 at 2:13 pm #79733I have written a couple of blogs about chatGPT, beginners guide to chatGPT webinar and a couple of podcasts which you may find useful

https://www.elizabethahutchinson.com/post/chatgpt-and-school-libraries and 5 reasons school librarians are essential for teaching research skills

Webinar – ChatGPT and AI

I would also follow Leon Furze and Andrew Herft on LinkedIn… They are doing a lot of great stuff…

I have done 2 podcasts about ChatGPT as well… Here are the links. ChatGPT, school libraries, inquiry and questioning skills and ChatGPT for school libraries

Looking forward to discussing this more with you.

2nd March 2023 at 6:52 am #79773I have just come across Leon’s latest post on creating an AI policy for schools. Thought you might find it useful.

3rd March 2023 at 7:21 pm #79797Thanks Elizabeth – you’ve got my weekend reading sorted! I’m looking forward to having a look through these resources and listening to your podcasts. I would also direct people to John Royce‘s exceptionally well-researched and thoughtful blog posts on his Honesty, Honestly blog:

- Here we are again!, looking at whether it is possible to use “AI detectors” and how to “use [ChatGPT] as a spring board” and treat it “as a tool, not as an enemy…”

- Back to basics, again, reflecting on the proliferation or articles about ChatGPT and looking at it as a prompt to encourage critical thinking (as Google was before it) – this one contains the alarming quote “You may remember former Google CEO Eric Schmidt declaring, ‘I actually think most people don’t want Google to answer their questions… They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next’ (as quoted in The Atlantic article Google’s Growing Problem With ‘Creepy’ PR in October 2010).”

- To be verified…, reacting to the (possible) news in The Times that the IB would be allowing to use AI sources in their essays as long as they credited them.

I have a huge amount of respect for John Royce (as I do for you) as a very experienced and thoughtful IB Librarian trainer, and he researches his articles incredibly thoroughly. I actually use his article The integrity of integrity as one of my sources when I teach citing and referencing to Year 12 and 13 students in the hope that they will also engage with the content!

10th March 2023 at 5:56 pm #79870Thank you for these links, which I will explore. I am reflecting on the following…

ChatGTP was first released by OpenAI on 30 November 2022.

In an article unrelated to ChatGTP, and published at practically the same time on 2 December 2022, Cory Doctorow makes the following point in How tech changed global labor struggles for better and worse:

The original sin of both tech boosterism and tech criticism is to focus unduly on what a given technology does, without regard to who it does it to and who it does it for. When it comes to technology’s effect on our daily lives, the social arrangements matter much more than the feature-sets.

This strikes me as precisely the place to start thinking from.

At the same time I happened to be re-reading Neil Postman‘s The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (1996), which expresses similar concerns. In it Postman makes the point that what we need to know about important technologies “is not how to use them, but how they use us” (p. 44).

Postman goes on to say (p. 44):

I am talking here about making technology itself an object of inquiry, so that Little Eva and Young John in using technologies will not be used or abused by them, so that Little Eva and Young John become more interested in asking questions about the computer than in getting answers from it.

Postman elaborates on this (pp. 188-193, emphasis added), with specific reference Marshall McLuhan:

McLuhan comes up here because he is associated with the phrase “the extensions of man.” [This brings me to] my third and final suggestion [which] has to do with inquiries into the ways in which humans have extended their capacities to “bind” time and control space. I am referring to what may be called “technology education.” … Technology may have entered our schools, but not technology education. …

McLuhan, while an important contributor [to the great story of humanity’s perilous and exciting romance with technology], was neither the first nor necessarily the best who has addressed the issue of how we become what we make. … This is a serious subject. …

[My suspicion for why there is no such subject in most schools] is that educators confuse the teaching of how to use technology with technology education. … As I see it, the subject is mainly about how [technologies] reorder our psychic habits, our social relations, our political ideas, and our moral sensibilities. It is about how the meanings of information and education change as new technologies intrude upon a culture, how the meanings of truth, law, and intelligence differ among oral cultures, writing cultures, printing cultures, electronic cultures. Technology education is not a technical subject. It is a branch of humanities. Technical knowledge can be useful, [but it is not necessary] …

It should also be said that technology education does not imply a negative attitude toward technology. It does imply a critical attitude. … Technology education aims at students’ learning about what technology helps us to do and what it hinders us from doing; it is about how technology uses us, for good or ill, and how it has used people in the past, for good or ill. It is about how technology creates new worlds, for good or ill. …

But in addition [to all the questions I have cited], I would include the following ten principles [in this subject]:

- All technological change is a Faustian bargain. For every advantage a new technology offers, there is always a corresponding disadvantage.

- The advantages and disadvantages of new technologies are never distributed evenly among the population. This means that every new technology benefits some and harms others.

- Embedded in every technology there is a powerful idea, sometimes two or three powerful ideas. Like language itself, a technology predisposes us to favor and value certain perspectives and accomplishments and to subordinate others. Every technology has a philosophy, which is given expression in how the technology makes people use their minds, in what it makes us do with our bodies, in how it codifies the world, in which of our senses it amplifies, in which of our emotional and intellectual tendencies it disregards.

- A new technology usually makes war against an old technology. It competes with it for time, attention, money, prestige, and a ‘worldview.’

- Technological change is not additive; it is ecological. A new technology does not merely add something; it changes everything.

- Because of the symbolic forms in which information is encoded, different technologies have different intellectual and emotional biases.

- Because of the accessibility and speed of their information, different technologies have different political biases.

- Because of their physical form, different technologies have different sensory biases.

- Because of the conditions in which we attend to them, different technologies have different social biases.

- Because of their technical and economic structure, different technologies have different content biases.

Finally, for now, I have just come across Noam Chomsky: The False Promise of ChatGPT (8 March 2023), a guest essay in The New York Times. I have not yet read this properly, but the following struck me as particularly insightful:

It is at once comic and tragic, as Borges might have noted, that so much money and attention should be concentrated on so little a thing — something so trivial when contrasted with the human mind, which by dint of language, in the words of Wilhelm von Humboldt, can make “infinite use of finite means,” creating ideas and theories with universal reach.

The human mind is not, like ChatGPT and its ilk, a lumbering statistical engine for pattern matching, gorging on hundreds of terabytes of data and extrapolating the most likely conversational response or most probable answer to a scientific question. On the contrary, the human mind is a surprisingly efficient and even elegant system that operates with small amounts of information; it seeks not to infer brute correlations among data points but to create explanations.

Next week I hope to integrate this practically with what I have written so of our academic integrity policy.

11th March 2023 at 11:34 am #79871I corrected some typos above.

To reiterate, Postman is not arguing against learning how to use technology, only that this is less important than learning about the changes that technology brings about – changes brought about by whom, to whom and for whom.

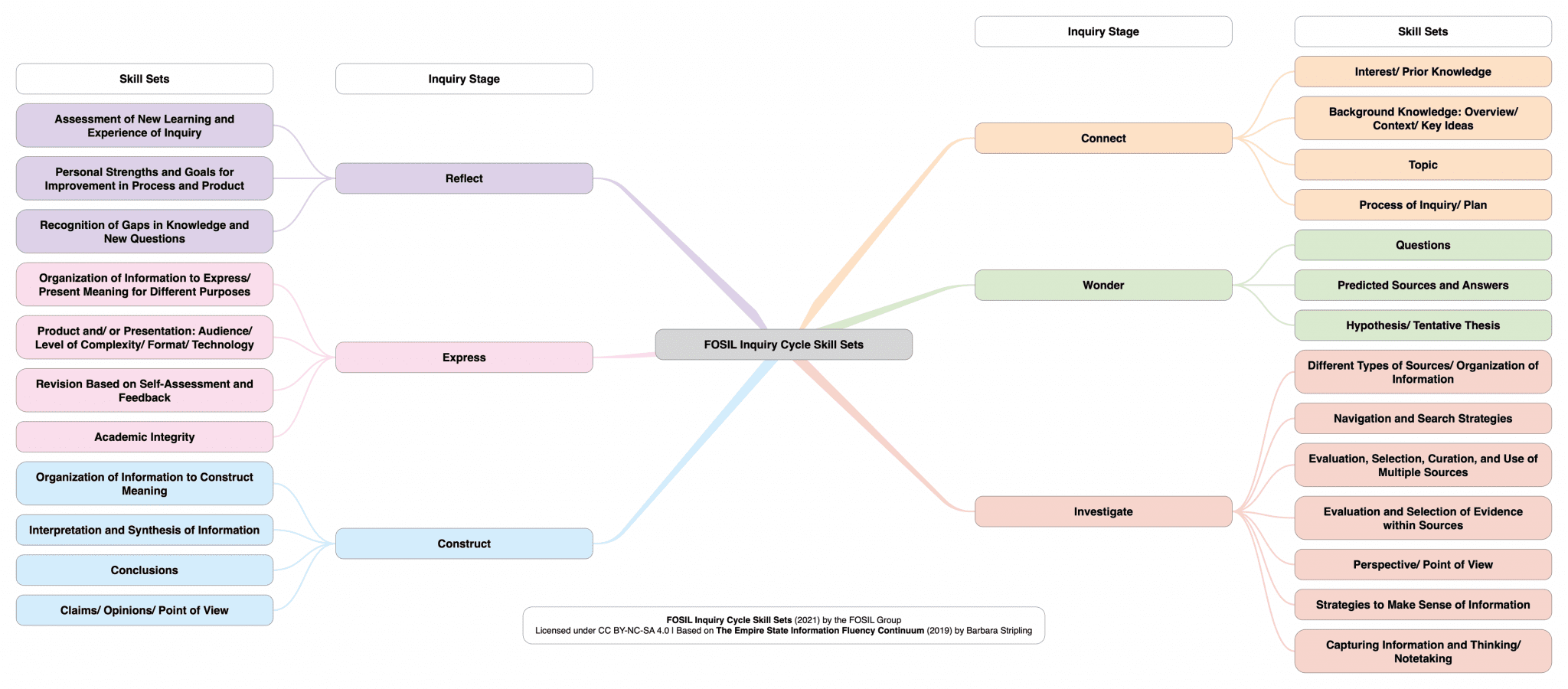

ICT and/ or Computer Science present(s) an obvious and important opportunity to deal with some of this subject’s matter, but not all. Allied to this is the library’s inquiry-centred instructional programme and curriculum, which I will elaborate on in relation to our academic integrity policy.

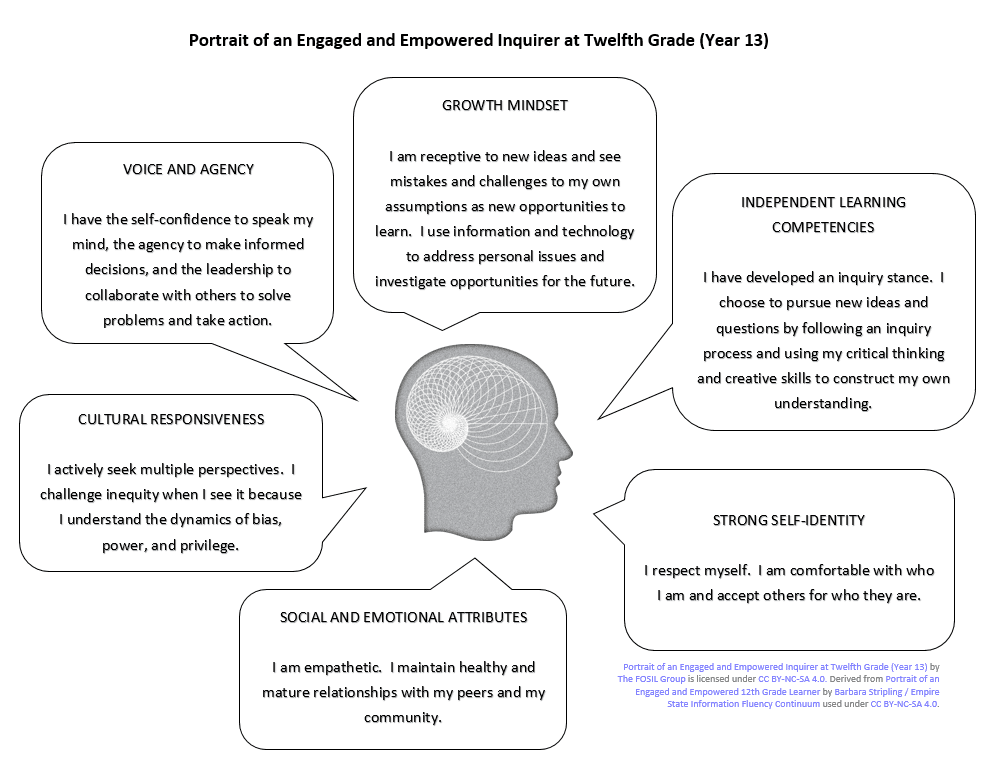

Finally, Chomsky’s view touched on above seems to me to cry out for school librarians who are, in Barbara Stripling‘s terms, teachers of sense-making skills (see E&L Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry).

24th March 2023 at 6:49 pm #79987

24th March 2023 at 6:49 pm #79987The release of GPT-4 – and the accompanying “storm of hype and fright” (Charlie Beckett in the Guardian on 17 March 2023) – prompted me to revisit Doug Englebart‘s most seminal work, Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework (1962).

In Augmenting Society’s Collective IQ (2004, adapted by Christina Engelbart in 2010 and 2015), Engelbart writes:

The complexity and urgency of the problems faced by us earth-bound humans are increasing much faster than our combined capabilities for understanding and coping with them. This is a very serious problem. Luckily there are strategic actions we can take, collectively.

It is against this backdrop that he wrote:

By “augmenting human intellect” we mean increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems. Increased capability in this respect is taken to mean a mixture of the following: more-rapid comprehension, better comprehension, the possibility of gaining a useful degree of comprehension in a situation that previously was too complex, speedier solutions, better solutions, and the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insoluble. … We do not speak of isolated clever tricks that help in particular situations. We refer to a way of life in an integrated domain where hunches, cut-and-try, intangibles, and the human “feel for a situation” usefully co-exist with powerful concepts, streamlined terminology and notation, sophisticated methods, and high-powered electronic aids. … Augmenting man’s intellect, in the sense defined above, would warrant full pursuit by an enlightened society if there could be shown a reasonable approach and some plausible benefits.

It seems to me that “the complexity and urgency of the problems [facing us continue to increase] much faster than our combined capabilities for understanding and coping with them,” and that at some point this must become a critical problem. It also seems to me that this is in some part, perhaps a large part, due to a failure of school to educate towards “more-rapid comprehension, better comprehension, the possibility of gaining a useful degree of comprehension in a situation that previously was too complex, speedier solutions, better solutions, and the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insoluble.” At the same time, our “high-powered electronic aids” evolve ever faster, and this has resulted in the technological means for augmenting our intellect outpacing the development of our individual and collective intellect, and becoming an end in itself.

Although he may not have had this precisely in mind, Postman is right in saying that “of all the ’survival strategies’ education has to offer, none is more potent … than the ‘inquiry environment’” (1971, p. 36), provided that we resist the tendencies that rob the inquiry environment of its potency (which we intend to address at the IASL 2023 Annual Conference in Rome – see Recovering the Educational Promise of Inquiry for presentation). This is because inquiry has engaged and empowered inquirers as its end, which includes the thoughtful use of rapidly-evolving “high-powered electronic aids” to augment our individual and collective intellect.

Bibliography

- Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. (1971). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

5th April 2023 at 1:04 pm #80077I just thought I would share my latest podcast with you. Empowering learning through ChatGPT: Insights from school librarians. I was joined by John Royce, Jeri Hurd, Susan Merrick and Sabrina Cox.

8th April 2023 at 10:38 am #80096Thank you, Elizabeth et al – very interesting, and I know that Jenny has some thoughts to contribute.

I have made some practical progress towards our academic integrity policy, which I will share later. However, I came across the following in Bertrand Russell’s, The Impact of Science on Society (first published 1952):

Broadly speaking, we are in the middle of a race between human skill as to means and human folly as to ends. Given sufficient folly as to ends, every increase in the skill required to achieve them is to the bad. The human race has survived hitherto owing to ignorance and incompetence, but, given knowledge and competence combined with folly, there can be no certainty of survival. Knowledge is power, but it is power for evil just as much as for good. It follows that, unless men increase in wisdom as much as in knowledge, increase of knowledge will be increase of sorrow. (1976, p. 110)

This brings to mind H.G. Wells in The Outline of History:

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe (1920, Volume 2, Chapter 41, Section 4).

However, education can only avert catastrophe if it does not confuse means for ends, and, given that even educational ends are contested, its end is “transcendent and honorable,” for without such an end, “schooling must reach its finish, and the sooner we are done with it the better” – with such an end, however, “schooling becomes the central institution through which the young may find reasons for continuing to educate themselves” (Postman, The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School, 1995).

19th April 2023 at 12:00 pm #80200I have come across three articles/ views for further consideration:

- Moving slowly and fixing things – We should not rush headlong into using generative AI in classrooms (LSE Impact Blog, 1 March 2023, by Mohammad Hosseini, Lex Bouter and Kristi Holmes) | “Reflecting on a recent interview with Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, [the authors], argue against a rapid and optimistic embrace of new technology in favour of a measured and evidence-based approach.”

- ‘I didn’t give permission’: Do AI’s backers care about data law breaches? (The Guardian, 10 April 2023) | “Regulators around world are cracking down on content being hoovered up by ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion and others.”

- AI is remaking the world on its terms, and that’s a problem (Fast Company, 19 April 2023, by Zachary Kaiser) | “Artificial intelligence is making it harder for humans to have agency in their own lives.”

While all three of these articles/ views strike a chord with me, the one that resonates most deeply is AI is remaking the world on its terms, and that’s a problem.

29th April 2023 at 12:59 pm #80286Another interesting article: Why ChatGPT lies in some languages more than others in TechCrunch (26 April 2023, by Devin Coldewey) | “AI is very much a work in progress, and we should all be wary of its potential for confidently spouting misinformation. But it seems to be more likely to do so in some languages than others. Why is that? … It’s already hard enough to tell whether a language model is answering accurately, hallucinating wildly or even regurgitating exactly — and adding the uncertainty of a language barrier in there only makes it harder. … It reinforces the notion that when ChatGPT or some other model gives you an answer, it’s always worth asking yourself (not the model) where that answer came from and if the data it is based on is itself trustworthy.”

—

Assuming that we can overcome these and other legal and ethical objections to using ChatGPT et al (see posts above), what practical objections might we need to overcome, bearing in mind that our fundamental concern here is with augmenting the intellect of our students?

Inquiry, remember, is a response to the desire to know and understand the world and ourselves in it – in other words, reality. This point is worth labouring because everything else hinges on it, and Charles Sanders Peirce (1955, p. 54) makes it powerfully:

Upon this first, and in one sense this sole, rule of reason – that in order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so desiring not be satisfied with what you already incline to think – there follows one corollary which itself deserves to be inscribed upon every wall of the city of philosophy: Do not block the way of inquiry.

Peirce draws our attention to two deeply interrelated things. Firstly, without a desire to learn, the process of learning about reality, which is an inquiry process, is not possible – this should be obvious, but apparently isn’t. Secondly, in desiring to learn, we must also be willing to learn, which is to be open to being changed by what we learn. So, without a desire to learn and an openness to being changed by what we learn, learning is not possible.

These insights highlight the importance and value of the Connect stage, which serves to engage students in the learning process – fanning, or more likely awakening, the desire to learn. Having engaged students in the learning process, Connect also serves to ground and orientate the learning process – identifying what is known, or seems familiar, and gaining a sense of what is unknown, or unfamiliar. This is crucial, because the process of learning about the world and ourselves in it, which is a knowledge-building process, requires information about the world and our place in it. If this knowledge-building process is to be sound, then the information that it depends on needs to reliable. Danny Hillis (2012), in The Learning Map, develops the idea that we ought to be able to learn anything for ourselves with suitable guidance. ChatGPT et al has an obvious role to play here as a guide, but its unreliability as a guide severely limits this role, at least for the time being. As the article referenced above puts it, “it’s already hard enough to tell whether a language model is answering accurately, hallucinating wildly or even regurgitating exactly — and adding the uncertainty of a language barrier in there only makes it harder”. Given this, and also in the words of the article referenced above, “when ChatGPT or some other model gives you an answer, it’s always worth asking yourself (not the model) where that answer came from and if the data it is based on is itself trustworthy”. From what age can we reasonably expect our students to be able to ask these questions, let alone answer them, and from what age can we realistically expect our students to make the effort to do so? In this regard, ChatGPT et al seems to combine the greatest temptations and pitfalls of Google and Wikipedia. This unreliability as a guide in the Connect stage similarly limits the role of ChatGPT et al in particularly the Investigate stage.

The process of gaining a sense of what is unknown, or unfamiliar, in Connect inevitably raises questions that then lead naturally into the Wonder stage, and this transition is crucial, for, as Hans-Georg Gadamer (1994, p. 365) points out, “to question means to lay open, to place in the open [and] only a person who has questions can have [real understanding]”. This presents another seemingly obvious role for ChatGPT et al, which is to help raise questions that are worthy of investigation. However, as Jerome Bruner (1960, p. 40) points out:

Given particular subject matter or a particular concept, it is easy to ask trivial questions….It is also easy to ask impossibly difficult questions. The trick is to find the medium questions that can be answered and that take you somewhere.

These medium questions that can be answered and that take you somewhere are fruitful questions, and they must belong to our students if they are to be fruitful, in that being able to answer these questions matters more to our students than merely finding answers to them. This distinction is crucial, because it makes the difference between finding information that appears to answer a question that you do not care about, and therefore have invested no thought in, and finding information that helps you to formulate a thoughtful answer to a question that you care about answering. This also makes the difference between whether you are likely to care about the reliability of your information, or not. We have already noted the questionable reliability of ChatGPT et al as a guide to the information that is available in response to a question, and this brings into focus some of the limitations of ChatGPT et al in helping us to raise fruitful questions.

Given the extent to which our educational systems are likely to be focussed on students ‘learning’ answers to questions that are not their own, they are likely to need much guidance and support in developing fruitful questions of their own. This will require personal knowledge of the students that grows out of relationship with them. Broadly, this will be difficult, if not impossible, for ChatGPT et al. It is conceivable that, given a certain level of maturity, fruitful questions could emerge out of a ‘discussion’ between a student and ChatGPT, but, as above, we need to ask from what age can we reasonably expect our students to be able to have this kind of ‘discussion,’ and from what age can we realistically expect our students to make the effort to do so.

So far, it seems to me that the role of ChatGPT et al in actually augmenting student intellect is very limited, and therefore, at best, an unhelpful distraction in our work with them.

References

- Bruner, J. (1960). The Process of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (1994). Truth and Method. London: Continuum.

- Hillis, D. (2012, July 19). OSCON 2012: Danny Hillis, “The Learning Map”. Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wKcZ8ozCah0

- Peirce, C. S. (1955). The Scientific Attitude and Fallibilism. In J. Buchler (Ed.), Philosophical Writings of Peirce (pp. 42-59). New York, NY: Dover Publications.

1st May 2023 at 3:26 pm #80287Two apologies – first that it has taken me a while to post because I have been unwell, and second that because it has taken me so long I have done an awful lot of thinking, so this has become a very long post!

I’ve been reading and thinking a lot about this topic recently – thanks Elizabeth for the interesting podcast link[i] (I’ve listened to that twice now!), and Darryl for the rather disturbing articles. I must preface my thoughts by making it clear that I am not a Luddite. I left school at the point the world wide web was really taking off – email was a flashy new technology that I first encountered at university (which makes me seem very old to the children I teach – maybe I am!). But this has changed education for the better. Children (and adults) now are free to pursue their interests and teach themselves about topics that fascinate them to a level that was just impossible for previous generations. That very freedom brings a dizzying array of choices, some of which are more productive and some more ethical than others. Our role as librarians has changed subtly over the years from gatekeeper and curator of scarce resources to expert guide to overabundant resources – but is still just as important as it was, if not more so. I should also mention that although I refer to ChatGPT explicitly because a lot has already been written about it, much of my thinking applies to other AIs such as Google Bard and Bing’s AI.

I was fascinated by Elizabeth Hutchison, John Royce, Jeri Hurd, Susan Merrick and Sabrina Cox’s discussion. It was helpful to hear five information professionals who have been actively exploring this area reflecting on their experiences. I must confess that while I have been following the story carefully, I have not yet signed up to ChatGPT – largely because I have real data privacy concerns about giving my personal phone number to a company that has already used personal data is a way that is so ethically questionable that a few countries are banning it outright[ii] (although Italy has revised that decision[iii] now that Open AI has put some extra privacy features in place). I can see why they might want my email address. I cannot fathom an ethical reason why they need my phone number, and until I understand that I don’t want to give it to them. I will also not be setting any assignments that require my students to sign up. This interesting article highlights some of these concerns: ChatGPT is a data privacy nightmare. If you’ve ever posted online, you ought to be concerned[iv].

Beyond that, I think there are educational opportunities and also very serious educational concerns (beyond the obvious one of children getting chat GPT to do their homework for them).

In-built racism (and other forms of discrimination)

Jeri raised the important point in the podcast that the plagiarism checkers that have sprung up to spot AI generated work are much more likely to produce false positives for second language learners because their writing is less ‘natural’ and more like an AI. Unlike with previous plagiarism checkers (where you could often compare the work and the original sources side by side if necessary), it is impossible to prove either way whether a piece of work is AI generated because the answers are ephemeral. This seems to stack the odds against non-native speakers. There are also plenty of issues with the secrecy around the training material. It is already widely recognised that there the training sets used for facial recognition software led to inherent racism in the products and their use[v], without some scrutiny of the training material for AI systems, there is a strong likelihood and a fair amount of evidence already of inherent bias (see, for example the answer to Steven T. Piantadosi’s question[vi] about how to decide whether someone would make a good scientist).

None of this would matter so much if it was just an interesting ‘toy’, but early indications as far as I can see are that it is being adopted unquestioningly and enthusiastically in a wide range of areas at an alarming rate.[vii]. We absolutely need to be educating our students about the moral and ethical issues involved and explaining the potential real world consequences – this is NOT just about them cheating in homework assignments or even coursework. The challenge is that it is hugely attractive in a wide range of applications because it offers easy but deeply flawed solutions.

Source credibility and downright lies!

In the podcast Susan describes asking ChatGPT and Google Bard to recommend fantasy series for a children aged 11-18 from 2015 –202 and to produce book blurbs for a display. It was astonishing to hear that ChatGPT made every single one of the book recommendations up (less astonishing to hear that the book summaries were poor). But how did Susan know this? Because she is an experienced Librarian who explored the book recommendations and quickly discovered they were fake, and who had read the books so knew the summaries/ recommendations were poor. She was starting from a position of knowledge. Our children are usually starting from a position of relative ignorance about their topic and are much less likely to spot the blatant lies (sorry – I believe technical specialists prefer the term ‘hallucinations’).

Even the CEO of Open AI said on Twitter[viii] in December 2022 that “ChatGPT is incredibly limited, but good enough at some things to create a misleading impression of greatness. it’s a mistake to be relying on it for anything important right now. it’s a preview of progress; we have lots of work to do on robustness and truthfulness.”

As EPQ co-ordinator (as well as further down the school) an important part of my job is teaching students to evaluate their sources – to look at where their information has come from, whether the sources are trustworthy for factual accuracy and what their bias is likely to be.

Chat GPT blows this out of the water.

It does not reveal it’s sources (and even if you ask it to, it is likely to make them up[ix]). So a student (or anyone else) getting information from ChatGPT cannot evaluate their sources for accuracy and bias because they have no idea what they are. Even worse, ChatGPT is very plausible but often just plain wrong. You cannot actually rely on anything that it tells you. If you need to verify everything it says (which I am not sure many students would do in reality) then I don’t see how it saves any time at all. It is a great deal worse than Wikipedia (which can – sometimes – be a helpful starting point, if only because it directs you to external sources which you might then be able to visit and use).

It plagiarises pretty much all its content

There has been a lot of talk about plagiarism by students and plagiarism detection (an arms race that I am not sure we can win), but rather less about plagiarism by ChatGPT itself. Noam Chomsky got a fair amount of press attention recently when he said that ChatGPT is “basically high-tech plagiarism”[x]. Now, although Professor Chomsky is an exceptionally experienced and highly respected educational thinker and linguist, a 94 year old may not be the first person you would turn to for opinions on emerging technologies. He is, however, spot on. ChatGPT takes information from unknown sources and presents it as its own work. And even when asked it is often unable to cite all (or even any) of its sources with any accuracy. How is that not plagiarism? How can we direct students to use a source that is itself so unethical? While I am a big fan of the IBO in many areas, I did find it hugely depressing that they are suggesting that ChatGPT should be a citable source in coursework[xi]. Of course, if you use a source you must cite it, but I think it is important to provide context (such as they might with Wikipedia) about what circumstances (if any) might make this an appropriate source to cite (e.g., if you were writing an essay ABOUT ChatGTP, perhaps).

To me citing an AI such as ChatGPT feels like citing ‘Google’ as a source. It isn’t a source. It is essentially a highly sophisticated search engine. You might as well cite ‘the Library’ or ‘Amazon’ as your source. It doesn’t tell your reader anything about the actual provenance of the information which, surely, is the main point of source citation. Having read the actual statement from the IB[xii] (and associated blog post[xiii]) on this, however, I understand the sentiment behind it. Better to find a legitimate way to allow students to acknowledge use of a new technology than to ban it, which is likely to mean they will just use it without acknowledgement.

Note that even where AI’s do cite actual sources, their lack of ability to actually understand them means that it is easy to cite them out of context – as in this hilariously depressing example[xiv] where Bing’s AI cited Google’s Bard as it erroneously claimed it had itself already been shut down.

It stunts thinking

Our SLS recently produced a very interesting infographic on ChatGPT based on Jeri Hurd’s work. I’m very grateful to them and her for the effort – I haven’t had time to produce anything similar – but I don’t feel I can use it because it is so overwhelmingly positive about ChatGPT and (as you can tell) I don’t feel that way. One of the suggestions is to ask it to produce an essay plan/ outline for you. Now, it may depend exactly what is meant by that, but as a bare statement I find it very uncomfortable. An essay plan, produced at the Construct stage, is a very personal path through your own journey from information to knowledge. It is your chance to pull together all the ideas you have discovered into something that is meaningful and coherent to you and to others. It is, in many ways, more important than the essay (or other product) itself.

If you outsource this thinking, you might as well not bother. As an educator I don’t want to know what ChatGTP ‘thinks’, I want to know what YOU think. There many other subtle and not so subtle ways in which AI tempts students because it will do their thinking for them (I was shown an ad on my Duolinguo app the other day, proudly telling me that I never needed to write an essay again if I downloaded a particular AI app). In Chomsky’s interview with EduKitchen[xv] he says that he does not feel that he would have had a problem with ChatGPT plagiarism with his students at MIT because they wanted the LEARN so they wouldn’t have touched it – he describes AI systems like ChatGPT as “a way of avoiding learning”.

It potentially ‘blocks the way of inquiry’

Many have suggested that the rise of AI such as ChatGTP will spell the end for coursework and make exams paramount again[xvi]. Now it is important to make it VERY clear that inquiry is not all about coursework – some of the richest experience I have had with inquiry have been preparing students for A-level exams. The potential demise of coursework would not reduce the importance of inquiry as an educational tool, but it would make it harder for it to get a foothold in an educational system already biased towards instructionist methods. At the moment skills lessons for coursework are a helpful way in for many librarians to forge new relationships with curricular colleagues and demonstrate what they can offer. With this avenue potentially closing, we as a profession will need to get more creative!

The other suggestion from the podcast that filled me with dismay was the suggestion that essays (including perhaps something like the Extended Essay) could be replaced by being given the draft of an essay and being asked to write the prompt to fix what was wrong with it. As one teaching tool among many, I can see how that could be useful, alongside comparing AI written sources with human written ones, but not to replace essay writing and inquiry themselves. The EE can be a life-changing experience of inquiry for some students, allowing them (often for the first time) to immerse themselves in pursuing their own lines of inquiry on a topic important to them over an extended period of time to produce something new and original. The magic of this would be completely lost if it was only about writing good questions or only about evaluating and improving AI answers to someone else’s question. Extended inquiry definitely still has a vital place – but we do have to work out how AI changes the landscape and how to work with new technologies without destroying what we had. One possible option is robust vivas (or presentations as is the case in the EPQ) accompanying all coursework submissions to make it clear which students actually understand their topics and which do not. But this is very staff and time intensive so I can’t see it catching on wholesale beyond the EE and EPQ.

Of course, there are some amazing inquiry opportunities investigating the technology itself, looking at what it can and can’t do, ethics and potential future uses and, as Jeri found, real opportunities for librarians to take a lead in the schools in terms of how to deal with this new reality. As long as ‘taking the lead’ doesn’t equate to cheerleading for it. I’m also quite interested in the idea of encouraging older students to ask it their inquiry questions and to critique the answers it gives – although I would rather they did that towards the end of their inquiries than at the beginning because I think this is best done from a position of knowledge than relative ignorance. I’d also have to choose an AI that I had fewer data privacy concerns about than ChatGPT, and use it as an opportunity to explore my other ethical concerns with students.

Digital divide

Alongside issues of inherent bias in the systems themselves, I do worry about overenthusiastic adoption of AI in education exacerbating the current digital divide. If AI becomes part of assessment (e.g., students being assessed on how well the write prompts, being allowed or even encouraged to use it in coursework etc.) then it does cause issues for those with less ready access to technology at home who have less opportunity to practice. In one sense this is an argument for using and teaching with AI in school to make sure everyone has some degree of access, but making it an inherent part of assessment has issues. Particularly also because there are already early steps to monetise access[xvii], which is not unreasonable because it is very costly to produce and run, but will create a two tier system. Perhaps it won’t be long before we start seeing ‘institutional access’ options for AI, alongside our existing databases…

So what can it and can’t helpfully do?

One of the most balanced analyses I have come across – neither enthusiastically pro or rabidly anti – is from Duke University in North Carolina. The full article[xviii] is definitely worth reading, but the summary of their suggestions is that ChatGPT could be good for:

- Helping you to broaden your existing keyword set at the start of an inquiry (‘What keywords would you use for a search on…?’).

- Identifying places to search for material (‘Which databases would you recommend for a project on…?’). [Note that this does not take account of paid databases that the user actually has access to via their Library but might be a good way to find free databases.].

- Suggestions for improving writing that you have already produced. [Careful with this one! At what point does the work become the AI’s and not yours? Matt Miller at DitchThatTextBook has an interesting take on that[xix]…There are already strict criteria from most exam boards about the support allowed with proofreading – check first!].

They suggest that it is NOT appropriate for:

- Finding lists of sources

- Summarising sources or writing a literature review [This reminded me of Jeri’s comments on the podcast about Elicit, which I was keen to have a play with. I will include a few comments on this in a separate post.]

- Making future predictions, or giving up to date information about current events

So what do WE do?

Inquiry should be a journey of discovery towards an answer that is personally important and meaningful. I also wholeheartedly agree with Noam Chomsky when he says ‘That students instinctively employ high technology to avoid learning is “a sign that the educational system is failing.” If it “has no appeal to students, doesn’t interest them, doesn’t challenge them, doesn’t make them want to learn, they’ll find ways out,”[xx]‘. If our inquiries are engaging and personal enough then students won’t want ChatGTP’s answers, they will want their own. But once again the bar has been raised for us – the fact that students have this option doesn’t mean we need to find better ways to catch them using it, or encourage them to use it because we know we can’t stop them, but that we need to raise our game again and make learning experiences increasingly meaningful to our students. It is also an opportunity for us as librarians, who are actively wrestling with these issues, to earn ourselves a position at the centre of this debate in our schools, as Jeri discussed doing so successfully on the podcast.

Bibliography

[i] Hutchinson E., Cox, S. (hosts). (2023, March 8). Empowering Learning Through ChatGPT and AI: Insights from School Librarians. [Audio podcast episode]. In School Library Podcast. https://ehutchinson44.podbean.com/

[ii] Pollina, E. & Mukherjee, S. (2023, March 3) Italy curbs ChatGPT, starts probe over privacy concerns. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/italy-data-protection-agency-opens-chatgpt-probe-privacy-concerns-2023-03-31/

[iii] McCallum, S. (2023, April 29) ChatGPT accessible again in Italy. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-65431914

[iv] The Conversation. (2023, February 18). ChatGPT is a data privacy nightmare. If you’ve ever posted online, you ought to be concerned. https://theconversation.com/chatgpt-is-a-data-privacy-nightmare-if-youve-ever-posted-online-you-ought-to-be-concerned-199283

[v] Najibi, A. (2020, October 24). Racial Discrimination in Face Recognition Technology. Science in the News. https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2020/racial-discrimination-in-face-recognition-technology/

[vi] Vock, I. (2022, December 9). ChatGPT proves that AI still has a racism problem. The New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/quickfire/2022/12/chatgpt-shows-ai-racism-problem

[vii] Jimenez, K. (2023, March 1). ChatGPT in the classroom: Here’s what teachers and students are saying. USA Today. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2023/03/01/what-teachers-students-saying-ai-chatgpt-use-classrooms/11340040002/

[viii] Pitt, S. (2022, December 15). Google vs. ChatGPT: Here’s what happened when I swapped services for a day. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/15/google-vs-chatgpt-what-happened-when-i-swapped-services-for-a-day.html

[ix] Welborn, A. (2023, March 9). ChatGPT and Fake Citations. Duke University Libraries. https://blogs.library.duke.edu/blog/2023/03/09/chatgpt-and-fake-citations/

[x] Open Culture. (2023, February 10). Noam Chomsky on ChatGPT: It’s “Basically High-Tech Plagiarism” and “a Way of Avoiding Learning”. https://www.openculture.com/2023/02/noam-chomsky-on-chatgpt.html

[xi] Milmo, D. (2023, February 27). ChatGPT allowed in International Baccalaureate essays . The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/feb/27/chatgpt-allowed-international-baccalaureate-essays-chatbot

[xii] International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2023, March 1). Statement from the IB about ChatGPT and artificial intelligence in assessment and education. https://www.ibo.org/news/news-about-the-ib/statement-from-the-ib-about-chatgpt-and-artificial-intelligence-in-assessment-and-education/

[xiii] International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2023, February 27). Artificial intelligence in IB assessment and education: a crisis or an opportunity? https://blogs.ibo.org/2023/02/27/artificial-intelligence-ai-in-ib-assessment-and-education-a-crisis-or-an-opportunity/

[xiv] Vincent, J. (2023, March 22). Google and Microsoft’s chatbots are already citing one another in a misinformation shitshow. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2023/3/22/23651564/google-microsoft-bard-bing-chatbots-misinformation

[xv] Chomsky, N. (2023, January 20). Chomsky on ChatGPT, Education, Russia and the unvaccinated. Edukitchen [video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IgxzcOugvEI

[xvi] Acres, T. (2023, April 21). ChatGPT will make marking coursework ‘virtually impossible’ and shows exams ‘more important than ever’. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/chatgpt-will-make-marking-coursework-virtually-impossible-and-shows-exams-more-important-than-ever-12861767

[xvii] Nolan, B. (2023, March 16). OpenAI’s new GPT-4 is available for ChatGPT Plus users to try out. Here are the differences between the free and paid versions of ChatGPT. Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/chatgpt-plus-free-openai-paid-version-chatbot-2023-2?op=1

[xviii] Welborn, A. (2023, March 9). ChatGPT and Fake Citations. Duke University Libraries. https://blogs.library.duke.edu/blog/2023/03/09/chatgpt-and-fake-citations/

[xix] Miller, M. (n.d.). How to define “cheating” and “plagiarism” with AI. DitchThatTextBook. https://ditchthattextbook.com/ai/#tve-jump-18606008967

[xx] Open Culture. (2023, February 10). Noam Chomsky on ChatGPT: It’s “Basically High-Tech Plagiarism” and “a Way of Avoiding Learning”. https://www.openculture.com/2023/02/noam-chomsky-on-chatgpt.html

2nd May 2023 at 12:38 am #80288I was just listening to a fascinating programme on ChatGPT on BBC Radio 4 – Word of mouth: Chatbots. Really interesting conversation between Michael Rosen (multi award winning children’s author, poet, performer, broadcaster and scriptwriter) and “Emily M Bender, Professor of computational linguistics at the University of Washington and co-author of the infamous paper ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots’”. The segment I am listening to right now is on inbuilt bias in AI. Given Jeri’s concerns on Elizabeth’s pocast about Google Bard recommending Reddit as a source, I was startled to hear from Professor Bender that ChatGPT was trained by looking at sites linked by Reddit users (because that was the easiest way to get a lot of data where real humans link to a diverse range of topics). The whole episode is worth listening to, but that fact jumped out at me. I wonder whether that changes anyone’s view of the output of ChatGPT?

[Note that a quick websearch suggests that ChatGPT-2 was largely trained on sites suggested on Reddit, but -3 had significant additions to that training data (including the English Language version of Wikipedia). The training sources for -4 have not been revealed as far as I can tell. I haven’t found a suitably reputable source to link for this information, but have seen it on a number of different websites – if anyone has a good source for this, do post below. I did find this article from the Washington Post about Google’s AI dataset, which didn’t fill me with confidence about that either…]

Professor Bender also says “I like to talk about the output [of AI chatbots] as ‘non-information’. It is not truth and not lie….but even ‘non-information’ pollutes our information ecosystem.”

2nd May 2023 at 6:27 am #80289Hi Jenny, thanks for your very interesting and thoughtful comments. I too heard Michael Rosen’s interview and found it deeply worrying especially as many people seem to either be jumping headlong into the ‘what it can do for me’ or the ‘head in the sand’ camps and neither are helpful. I do feel that as school librarians we have to find a way to understand and work with it. These forum discussions are useful to all of us to help us understand and work out a way forward.

Highlighting the concerns is one way like you have above, but we also need to find ethical ways to work with it too. I remember when Wikipedia came into our schools and there was very clearly a wave of ‘you should not use it’ but if we had taken the time to understand it a little more we would have got to the place we are now, quicker. Which I feel is, like you said Jenny, ‘can be a helpful starting point’.

I do have concerns about students using it for research purposes without the knowledge and understanding about where the information comes from. This is an interesting role for school librarians and one we should not shy away from. Although there are many concerns I do think we need to find a positive way to use this technology. After all it is here to stay so lets find ways to use it ethically and cautiously. Our students of today will be using this technology within the professions of the future. We can’t put it back in the box and pretend it is not there.

I can understand why teachers are getting excited about using it as it seems to make the everyday tasks quicker, like lesson planning for example. It seems to me that if these tasks can be supported by AI then this is a positive thing.

We also need to remember that a large majority of our population, teachers and students have still not been anywhere near it, for some of the reasons you gave Jenny such as, no access to technology, but others really are not ready to work out what this can do yet or don’t see it as part of their lives.

This does not come across in main stream media or social media as you would imagine that everyone is engage which really is not the case. We are at the beginning of this wave and with our information expertise hats on we can be at the forefront of helping others find a way to work with it with understanding. We have always said that an independent learner is someone who know where to find the quality information quickly and this still is true. Just because AI is there does not mean it is the best place to find your answers and we just need to keep explain why this is still the case.

With all the concerns pointed out above and understanding that we can’t stop this wave. What can school librarians do practically and helpfully to work with AI in the future as well as highlighting its huge failings of course? Which in time will decrease I am sure.

10th May 2023 at 5:42 am #80344Good Morning All, Kay Oddone has just shared this article on Twitter written by Barbara Fister and Alison J. Head Getting a grip on ChatGPT Certainly and interesting read and one to add to our collection above.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.