Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment

Tagged: digital inquiry

- This topic has 35 replies, 8 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 11 months ago by

Rachel Huskisson.

Rachel Huskisson.

-

AuthorPosts

-

13th March 2021 at 1:49 am #38282

I love this conversation because your insights and challenges are making me think about the practical implementation of inquiry-based learning and teaching. Although I was a classroom teacher and a building-level school librarian for over 20 years, I have been engaged at a whole-district and library-educator level for the many years after that wonderful on-the-ground experience. I tend to think large picture and ignore the day-to-day implementation.

That being said, I would like to counter your feelings of lack of preparation for the paradigm shift because you were not trained as a teacher. I regard the librarian role as a fellow learner as well as a teacher. I have learned the most about the skills I need to teach students by engaging in inquiry as a learner myself and reflecting on the process. How did I find a topic that I was passionate about? Where did I seek information? How did I make sense of the information I found? What did I do if the sources were too pedantic and complex for my taste? I actually have two topics that I have been pursuing for years, just because I’m interested in them. As I thought about my own research, I discovered several tendencies that I am ashamed to admit, but that are pretty common with students. I succumb to confirmation bias, I interpret meaning based on my own assumptions and making quick inferences from headlines and graphics, I quit looking when I cannot easily find “good” information, and on and on.

By looking at my own inquiry learning, I developed a level of comfort in my inquiry-based teaching. I could identify the skills I needed to teach. When I then went to the next step of thinking about how to teach those skills, I did rely on my teaching background briefly to structure the lesson in four phases: direct instruction, guided practice, independent practice, and sharing and reflection. But what unlocked the content of direct instruction and guided practice for me was, once again, putting myself in the learner’s role. I remember trying to develop a lesson on inference. I know how to make inferences and always used to tell students to make inferences while they read. But some students don’t know how to make inferences. I challenged myself to think through my mental process in making an inference – what were the steps I had to go through to perform the skill? I then was able to select text about a sample topic and transparently model my own thinking as I was making inferences (direct instruction). Then I guided students to think through the process as they were making inferences from a different passage of text (guided practice). I provided students with graphic organizers to lead them through the steps during independent practice. Then we came together to share inferences and reflect on what students had learned about making inferences.

I have one other comment that I think is relevant at this point in our conversation. I do not believe that the only time to teach relevant inquiry skills is when students are engaged in a full inquiry project. If we are reading a story to early elementary students, we are teaching skills of inquiry when we ask them to make predictions from the cover, or compare the feelings of two different characters, or interpret the meaning of the illustrations, or state the main idea of the story. I have been doing some learning recently about the deep reading skills that are necessary and integral for inquiry. When we know that a history teacher is preparing to cover a particular era, we can curate high-quality resources and offer to teach students one important skill as a part of that classroom work (e.g., to identify point of view, interpret visuals, or question the text to uncover the explicit and implicit meanings in those sources). My thinking is that we can start the journey toward inquiry in our schools by infusing the skills of inquiry throughout the curriculum and being transparent to the students and teachers that the skills they are learning in their classroom assignments will all come together and empower them to be successful at larger inquiry projects.

Although it may seem that we are ahead of you in implementing inquiry-based learning through our school libraries in the United States, I can assure you that we are not. We’re in this learning path together. This conversation is helping me figure out how to shift the traditional paradigm of the school librarian’s role to become the facilitator of a school-wide inquiry stance.

13th March 2021 at 12:57 pm #38339This has been the strangest of weeks, which has meant that I have not yet been able to contribute to this fascinating discussion, although I hope to do so properly tomorrow.

Two things for now, though.

Firstly, Barbara makes the enormously important point that “she has learned the most about the skills she needs to teach students by engaging in inquiry as a learner herself and reflecting on the process”. My journey to inquiry – which began in 2008, resulted in FOSIL in 2011, and continues beyond 2021 – started with an inquiry. If we are expecting students in Year 12 (Grade 11) who have chosen to do the IB Diploma Programme – which requires them to complete the compulsory Extended Essay, which requires them to cite and reference to a recognized bibliographic standard – to cite and reference to a recognized bibliographic standard, then how do we effectively equip them for this requirement systematically and progressively in all of their years leading up to Year 12? This led me to what I mistakenly thought was an information literacy framework – FOSIL originally stood for Framework Of Skills for Information Literacy – but, serendipitously, turned out to be Barbara’s framework of the inquiry process and underlying framework of inquiry learning skills. I had an opportunity to reflect on this incredibly steep learning curve in an interview with Elizabeth, which I hope will serve as both inspiration and encouragement on this journey that we are all still on – see An Extraordinary Journey: FOSIL (Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning).

[Edit: I forgot to mention in this regard that the tag line for FOSIL is Learning by finding out for yourself (not by yourself, which suggests minimal or no guidance and/ or interventions). This is as true for our students as it is for us. This is also necessitated by the situation that many of us find ourselves in, which Ruth raises above about the lack of specialist sector training, which I also touch briefly on below.]

Secondly, this paradigm shift, which we should continue discussing, coincides with what may be another paradigm shift, which is the shift from a predominantly print to a predominantly digital environment, and which we should begin discussing. This paradigm shift, which I think it is, presents us with opportunities, but also challenges. We should, therefore, give some thought to what, if anything, fundamentally changes when we shift from a predominantly print to a predominantly digital environment. Two examples come to mind:

- If our students struggle to read print texts thoughtfully, which they appear to do, then they are likely to struggle much more with reading digital texts thoughtfully, and for a range of reasons. Is this essentially the same problem, or a fundamentally different one?

- In reading Jacques Ellul, I came to appreciate that a sufficient change in quantity results in a change in quality, which, in turn, requires a different response. So, when information, which knowledge is constructed from, is scarce, then the problem is finding reliable information. However, when we are confronted with a superabundance of information, then the problem becomes discerning reliable information, which may appear to be the same, but is qualitatively, and therefore fundamentally, different, I think.

Finally, in passing, school librarians are teachers, regardless of whether they, or anyone else for that matter, recognize this. The challenge for many of us, as Ruth points out, is that our profession may not recognize this, which then makes developing ourselves as specialist teachers, which we are, significantly more challenging.

17th March 2021 at 2:52 pm #39094Thank you all for what you have said, it’s both providing reassurance and helping me to develop my understanding in this area.

To answer one of Darryl’s points about the shift to a predominately digital environment.

I know from my own experiences that reading on a screen isn’t as easy as in print form (I printed off the article we’re discussing as I can’t read something like that on a screen). We know about using things such as post-it notes, highlighters, pen and pencil when we’re reading a printed text, but I think we do need to give some thought to how this might work in a digital environment. It’s a real challenge as people can be working on a device ranging from a phone to a large PC or laptop and whilst there are virtual post-it notes, they are often fiddly to use. Saying that there are advantages to the digital environment; such as the ability to enlarge text, change the colour of the background or even have the text read to you. I think it’s important that at the very least we acknowledge the difficulties of reading on screen as then the pupil knows that it is not just them who struggles.

18th March 2021 at 10:31 am #39249I think this article makes some interesting points about the mental shift required to support digital inquiry versus bibliographic inquiry. I know I have had occasions of disappearing down the digital rabbit-hole that Barbara describes and I am sure many others have too.

I think this links up to topical issues such as fake news. It is relatively straightforward for a librarian to weed through the bibliographic sources to ensure they’re reasonably accurate and reliable. Checking for out of date material is a long-accepted part of the librarian’s role. However, this is not something librarians are able to do for digital sources in the same way and students need to be able do a lot of that weeding for themselves – but that requires teaching them how to do so.

Learning how to assess the biases present in online sources, weigh up their relative merits, and decide how much weight to give to each one is an important skillset and becoming ever more so given social media’s tendency to become an echo chamber for one point of view once you start to disappear down the aforementioned rabbit-hole.

This links into the inquiry process as a whole because if you are using digital sources you need to first find them (and Barbara makes some useful comments about the need for librarians to know some of the nitty gritty of using search terms etc) but then to assess their value.

Both these points strike me of practical value that I can be quietly encouraging amongst students using the computers in my library even when they’re not doing a full-scale inquiry, but are simply trying to look something up for a smaller piece of homework.

Darryl’s point about reading digital sources is also relevant as it can, I believe, at times be easy to skim over writing on screen without really taking the information in. I watched a short video by Alex Quigley of the Education Endowment Foundation on this subject last year. The link to that and the research sources he based it on is: https://www.theconfidentteacher.com/2020/07/reading-on-screen-a-warning/

20th March 2021 at 11:29 am #39612(I’m going to apologise in advance – I find it really hard to think ‘out loud’ in small chunks, which would probably be more helpful for a discussion like this, and which all of you seem to do so well. Curiously in that sense, given the topic under discussion, I am perhaps less at home in the fast-paced digital environment than many of you! I having been reading and thinking about all the interesting ideas here and in the chapter and now find myself with a little bit of time to contribute to the discussion, so it is all likely to come flooding out over several longish posts. Sorry!)

We have a lot to thank the democratizing power of the digital environment for – without it we wouldn’t be having this discussion here. The internet is an amazing professional development tool, but is as much a problem for us as for our students. How do we make sure that we are learning from ‘experts’ rather than just those with the loudest voices? What makes an expert these days? Has the digital environment changed that? In the past there were high barriers to getting your voice widely heard. That didn’t mean, for example, that ‘bad’ books (by which I mean inaccurate, poorly researched or heavily biased) didn’t get published, but they were arguably much less common that ‘bad’ digital resources are today. Equally, there was almost certainly much that wasn’t widely shared or published that would have been of great value, and collaboration such as this across large distances by professionals who may often work alone was much more complicated (as evidenced by some of the fascinating letters between great academics of history!).

Barbara’s comments about the four phase lesson model (direct instruction, guided practice, independent practice, sharing and reflection), both in this forum and in her chapter really struck me because I think that many anti-inquiry direct-instruction enthusiasts would be very surprised to see an inquiry specialist advocating this approach. The false direct-instruction vs inquiry-learning debate does a lot of harm to education in general because it forces good educators into taking extreme positions – and generates a lot of guilt because these positions are ultimately untenable at both ends of the spectrum. Constructivism (and inquiry) is a stance, not a teaching method. It is about supporting (and challenging) children to find a personal connection with a topic and to construct their own firm understanding of it through experience, NOT about abandoning children to figure out thousands of years of academic progress by themselves (a concern raised with me yesterday by a Science colleague who is very interested and engaged in educational debate and progress in our school, is very open to the idea of inquiry and for whom I have a huge amount of respect). As such, direct instruction is one of a number of very valid tools that we can use during PART of an inquiry. The main differences between constructivist and instructivist approach show more in the nature and content of the four phases.

I mention this in part because of the debate we have been having here about teaching experience and qualifications. I think it is important to understand what we bring to the table as Librarians. I have found my teaching experience and training very useful, but Politics teachers in my school don’t want to talk to me about planning inquiries because I was a Physics teacher (they could talk to any of their Physics colleagues for that). They want to talk to me because I am a Librarian. It takes time and experience to build confidence with this – but you can start small with individual skills sessions, building confidence and relationships. Professional development opportunities and discussions like this are also very valuable, as is the opportunity to kick ideas for individual inquiries around in the forum. It still amazes me that I can add value to the teaching of even subjects I have never studied, and I still feel nervous approaching a meeting about a brand new inquiry. But as the conversation begins it becomes clear that my perspective is very different because I am not a subject specialist, and have experience of inquiry across other disciplines, which my subject colleagues don’t have, and this helps us to shape something better together than we could have done alone. It is also worth remembering that we are not suggesting that we offer something magical that our subject colleagues couldn’t do if they invested enough time and energy into it – more that we are investing our time in inquiry while they invest theirs in their specialism so that together we can achieve more. We are all on a journey, and there will always be people ahead of us who can offer help and people behind who need our support. And however uncertain we feel, we are usually ahead of our classroom colleagues on the inquiry journey simply because we have chosen to invest our time in it.

[More to follow relating more specifically to the digital environment and to Barbara’s fascinating and thought provoking chapter.]

20th March 2021 at 1:49 pm #39632I am particularly interested in how we counter and mitigate some of the more negative aspects of the digital environment, in order to benefit from the more positive ones. In this post I wanted to focus on the act of reading itself in the digital environment.

Reading in print and online are clearly different, and Barbara’s chapter prompted me to explore this further. This blog article led me to this excellent meta-analysis (Delgado, Vargas, Ackerman and Salmerón, 2018), which found that there is significant evidence to suggest that reading comprehension is better for print texts than digital ones, especially when:

- Under time constraints

- Reading informational rather than narrative texts

(both likely conditions during inquiry).

Moreover, readers of digital texts (under time constraint) were more likely to be overconfident and predict that their understanding was better than it actually was. The ‘screen inferiority’ effect increased over the 18 years prior to the study, suggesting that children who have grown up in a digital environment are actually less likely to understand as well from digital texts as from print versions. Delgado, Vargas, Ackerman and Salmerón (2018, p.34) state that “If simply being exposed to digital technologies were enough to gain these skills, then we would expect an increasing advantage of digital reading, or at least decreasing screen inferiority over the years”, implying that digital reading skills need to be taught.

There are suggestions that the digital environment promotes a shallower engagement with texts (known as the Shallowing Hypothesis), which can spill over into engagement with print texts – and one article I read while thinking about this (which I now can’t find – can anyone help me with the evidence here?) suggested that the effects that reading digitally have on comprehension and concentration can spill over into our interactions with print texts. So someone who spends a lot of time reading on screens may then find it harder to concentrate for the length of a print book. Anecdotally this resonates because we see in our reading lessons how hard many children find it to concentrate on just sitting and reading a book for 40 minutes. Was this always the case? Has the digitally connected world they inhabit made it worse? (Or did I just not notice it when I was growing up because I and my friendship circle were readers?)

The study states that “[a]n encouraging finding from Lauterman and Ackerman (2014) and Sidi et al. (2017) is that simple methodologies (e.g., writing keywords summarizing the text, framing the task as central) that engage people in in-depth processing make it possible to eliminate screen inferiority, in terms of both performance and overconfidence, even under a limited time frame” (Delgado, Vargas, Ackerman and Salmerón, 2018, p.35), but cautions that “Lauterman and Ackerman (2014) found that methods to overcome screen inferiority are effective only for people who prefer digital reading, but not for those who prefer paper reading” (p.24). It also suggests that by reading in a digital environment students drop an average of 2/3 of a year of the average reading comprehension progress they would make at elementary school, which is fairly significant.

So what can we do?

- The digital environment promotes broad shallow reading, and there are stages of inquiry that suit that. In some ways it is ideal for Connect (except that finding what you need online when you aren’t yet quite sure what you are looking for can be a challenge!). Perhaps an argument for a set of curated, linked online resources at the start of an inquiry that students can explore during the Connect stage. Particularly if it is a more open inquiry. Curiously we have tended to go in the other direction out of necessity. When resourcing mixed (print and digital) inquiries we have tended to use more general books as a starting point, and then allow students to explore online once they have a clearer idea of their topic. Largely because it can be difficult to find print resources that allow them to fully explore the questions that they generate.

- Lauterman and Ackerman’s finding (above) that simple active note-taking methodologies make a real difference to comprehension is very encouraging, and makes it even more important to teach effective note-taking in a digital environment. It would be interesting to pursue whether it makes a difference whether these notes are handwritten or not. I would imagine that the Construct graphic organisers we use also help to promote comprehension and narrow the gap between print and digital reading in a similar way. The other interesting finding here is that this only works for those who prefer digital reading, making it important that students who prefer to read in print have access to a printer when working with digital resources. I certainly know some students in this category at IB DP level, who prefer to print articles they have found and keep them in a folder, rather than save them as PDFs or links. This can present its own citing and referencing issues if they do not make an appropriate note of the source and they need to be aware of this. I have suggested using the Annotated Bibliography on screen to keep track of their sources, and the Investigative Journal in print in this case.

[Note that the flip side of the coin, beyond the scope of the study, is the impact of digital tools like Immersive Reader to support struggling readers and enable them to access information that might otherwise be beyond their reach.]

- For some inquiries where we have curated a set of resources (print and/or online) in advance, it might be worth providing these as a print pack where possible and appropriate. We have done this in the past where computer rooms were not available or where we preferred to keep students in the classroom for some reason, but maybe there is an argument for this as a more deliberate strategy in some cases.

- Perhaps encourage deeper reading by clearly distinguishing between ‘exploration’ time and ‘deep reading’ time, requiring students to nominate a small group of resources that they will stick to and read more deeply at a certain point, whether in print or on screen.

- Making students aware of the research, so that it can inform their metacognitive reflections – especially given the ‘overconfidence’ finding. There could actually be a great inquiry topic on exploring the effects of reading online…

- Make time and space for students to read print resources. Focusing on reading a book (fiction or non-fiction) for any length of time is a skill that needs to be practiced. Reading lessons do still matter at secondary level and we need to fight for them in our schools.

I would also suggest that the ability to search within texts on a digital environment gives students the ability to access information in texts that might otherwise prove too challenging for them (due to their length). This is a double-edged sword – particularly in the light of the decontextualization that Barbara discusses.

[I have been meaning to read Maryanne Woolf’s “Reader, come home: The reading brain in a digital world” for a while now, and this discussion has finally prompted me to take it out the library. Now I just need to tear myself away from screens for long enough to read it! 😊]

What do other people think? What do you do to mitigate the negative effects of the digital environment and promote the positive ones? Have you noticed any effects of the digital environment on your students?

20th March 2021 at 3:17 pm #39643Barbara’s chapter has so much to explore that it is difficult to know where to stop, but my last comments (for now!) relate to source evaluation. This has always been an important part of our job as Librarians, however, as Stephanie says, the access to resources that students now have through the internet means that it is not enough for us to curate resources for students, they need to be able to evaluate them for themselves. This has long been a staple of Information Literacy teaching and is one of the many skills that Librarians continue to deliver, support and develop through inquiry.

We use the CRAAP test* with our students, and one of the complaints they often make is “but that will take too much time” – and that is part of the point. While it is very important to evaluate all the sources you use, this is especially important and particularly time consuming for sources from the free internet. While we don’t want to make the task so onerous that they don’t bother, equally there is no point making a very superficial evaluation of a website. That just promotes false confidence in poor sources. Making a reasonable effort with source evaluation also levels the playing field for books and databases – the extra effort to access these generally (but not always) more reliable sources seems worth it when balanced against the extra effort required to determine the value of a general internet source.

I strongly recommend John Royce’s excellent series of three articles entitled Not just CRAAP when preparing to teach source evaluation, as they really changed and expanded the way I thought about and taught this skill.

Source evaluation is also a good time to talk about bias and perspective and how to make sure you read a diverse range of points of view. Clearly the first step towards this is understanding how to identify bias, and recognising that all sources (and readers) have an inherent bias which can only be mitigated by recognising this and making an effort to read a ‘balanced diet’. In many senses we are better off in the digital environment than we were in a purely print environment because we have access to so many more points of view. It is also important to recognise, however, that while everyone may have an opinion, not all opinions are equal and, in considering all sides of an argument, students need to be able to sift out fact from opinion and carefully reasoned argument from assertion. It reminds me of the old adage “Keep an open mind, but not so open that your brains fall out“!

Which source evaluation tools do others use? Do you stick with one throughout the school, or use a range? How do you find your students get on with them?

*One of our science teachers was concerned enough about the name “CRAAP test” that she contacted the English department to check whether it was really OK to use the word crap in class! While on the one hand the name is intended to be humorous to help students to remember the acronym, it was a reminder that we need to be careful not to make staff (and possibly students) feel uncomfortable. (You’ll be unsurprised to learn, given that English texts at higher levels can often contain some challenging language, that the English department had no problem with the word CRAAP.)

21st March 2021 at 10:27 am #39823[I have posted this at the start of the Topic as well.]

The Q&A with Barbara Stripling will take place on Sunday 28 March 2021 at 2pm-3.30pm GMT / UTC and is centred on this discussion.

- Colleagues who wish to join us will need to register in advance using this link: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZYpcO-opzIiHNCSvWStj_j20TkaAszVOPYw

- After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

The Q&A will be recorded for colleagues who are not be able to join us for practical reasons.

As with everything on the FOSIL Group website, the chapter that we will be discussing – Empowering Students to Inquire in a Digital Environment – is free to download for purposes of the discussion here with the kind permission of colleagues at School Library Connection and Libraries Unlimited / ABC-CLIO.

While it will be possible to follow the discussion without joining the FOSIL Group, participating in the discussion will require registering for an account, which is free.

If inquiry, as we are coming to understand it, is “a dynamic process and stance aimed at building knowledge and understanding of the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community,” then inquiry in a digital environment is of vital concern for us, and we hope that many of you will be able to join us in this discussion, whether directly or indirectly.

23rd March 2021 at 10:56 pm #40307What an interesting discussion we are engaged in about inquiry in the digital environment. I have read each of your entries with great interest and find myself puzzling over many of the same issues as you. Although we know that there are many skills and attitudes that are important for inquiry learning itself, whether it is pursued in the print or the digital environment, I am intrigued by the new or enhanced competencies demanded by inquiry in the online context.

I would like to pose some areas that we might explore more deeply together in our conversation on March 28. I recognize the challenges inherent in each of these areas, but I am still trying to figure out how I might help students overcome those challenges. What practical strategies can we figure out together?

1. Visual literacy. The online environment uses visual images, placement, highlighting, color, and attention-focusing techniques to implicitly guide the reader’s sense-making. If something is set aside in a box or presented graphically, then the reader may automatically classify that information as more important than other information embedded in the text. The seduction of visuals may encourage our students to hop from one visual to the next, gathering superficial first impressions and losing the context of the surrounding text.

2. Homogeneity of online information. Darryl mentioned that, with the glut of information now available online, learners must shift their focus from simply finding information to assuming responsibility for determining the reliability of information. Part of the dilemma for students is that all online information can appear to be homogeneous, to have the same value and authority. Blogs, student projects, texts by both experts and nonexperts, organizational websites, opinion pieces, commercial messages – all can be designed to appeal and attract readers or at least clicks. Two aspects of the CRAAP test that Jenny referred to seem to be the most relevant to help students differentiate among seemingly equal sources – authority and purpose. How can we help students learn to determine both authority and purpose, select the most reliable information for their academic pursuits, and carry that discernment over to their personal online searching?

3. Diverse perspectives. I am troubled by the impact of the digital environment on the diversity of the content of the information that students find. I think it is difficult for students to find credible and authoritative information from diverse perspectives, both because it is difficult to figure out the search strategies that will yield equally valid information from different points of view and because we seem to be naturally inclined to succumb to confirmation bias. The lateral and linked nature of much online information offers students the opportunity to gather additional information by following the links in their initial source, but the linked information is, of course, written from the same perspective. How do we enable students to seek, find, and pay attention to diverse perspectives?

4. Deep reading. Students (and all of us, for that matter) tend to read online texts superficially. Several of you noted that you print out any document that requires deep reading and reflection; I do the same. I understand that we cannot expect our students to print out every article they encounter. There are a number of deep reading strategies that we should teach during the inquiry process, but I still have some questions about how to enable students to interact with online text, make sense of the information they find, and use that information to drive their original thinking and new understandings. I think students get a lot of value from taking notes and reflecting by hand, so I think I would forego teaching students online notetaking. Instead, I would expect students to use graphic-organizer notetaking templates that provoke their deep reading, thinking, and personal connections while they are taking notes. I would probably modify the graphic organizers to align with different formats of information (e.g., podcasts, photos, data sets). I am interested in practical strategies that others have developed to foster deep reading in the online environment.

Those are a few of the areas where we might explore in our conversation next Sunday. I look forward to meeting all of you online.

24th March 2021 at 6:54 am #40370I just wanted to briefly reply to Jenny’s comments. Thank you for pointing out that teachers are interested in your expertise in inquiry and not that you are a physics teacher. I really had never thought of it that way! If we become an expert then this is what they are after. If we are prepared to give it the time that it needs we will certainly become the expert that not only our teachers need but also feel more confident in what we are teaching.

There is so much to unpack here. Jenny your ‘what can we do’ list is very thought provoking and I can see many things that I have tried over the years listed here. I would agree that I find it difficult to read online deeply and do prefer to print out longer articles. It has also had an effect on my concentration levels of reading too. I find I have to allocate time to reading fiction otherwise I would just end up distracted by what I might be missing online. I wonder if our younger students will become more able to read everything online or if there will always be this divide with deeper reading in print?

I am also interested in the CRAAP test as I do think that we have probably moved on from evaluating websites this way. In some ways, a list of things to look out for is not always the best way to evaluate I feel as a website can’t always be judged this way. Unfortunately, it is too simplistic but time-consuming. An interesting take on this comes from Mike Caulfield called Getting Beyond the CRAAP test which made me think more deeply about how the internet has changed since such lists were created. I think what this shows is that school librarians have to keep moving forward too. I have often been caught out by feeling comfortable in my ‘new’ skill or tool, only to find out that actually I am now out of date and need to change my thinking or tool. I have to admit that I have yet to teach a website evaluation lesson without a list so would be interested to hear what a lesson without CRAAP would look like.

Finally, I am really looking forward to our Q&A on Sunday and am delighted to see Barbara’s ideas for our practical discussion.

24th March 2021 at 12:21 pm #40394In the interview Elizabeth links to with Mike Caulfield, he says: “Stuff is reaching us with minimal gatekeeping.”

I think that is the key point with digital data by comparison to print. Print has been through multiple gatekeepers: editors, publishers, booksellers and librarians. If it’s an academic article in a journal, it’s probably been peer-reviewed. However, someone can set up a website or a blog online or join a social media platform (often for free) and start sharing their own opinions. Some of these are so professional looking that it can be harder to differentiate between the reliable and the fringe. The links Jenny shared to John Royce’s articles illustrate how even things like the CRAAP Test can now flounder when faced with those circumstances, so is it so surprising that many adults do too.

Does that mean we should ditch the CRAAP Test? Maybe not. I can still see merit in teaching the points raised by it, but I think we need to look beyond it too. Appearances can be deceiving. Polished and professional looking websites can still be the home of extremist views. Perhaps we need to go back to that old adage: don’t judge a book by it’s cover.

25th March 2021 at 7:15 pm #40580A really interesting discussion here about the CRAAP test – and Elizabeth’s link to Getting beyond the CRAAP test is well worth following however I would say that the issue that both Mike Cauldfield and John Royce have with the CRAAP test is not the idea itself, more the way it is taught and presented. Yes, it can be presented as a mindless list of a million things to check off a list before you can use a website, and no, that isn’t helpful. Particularly if, as Mike says, in The problem with the checklist approach you ask students to look for outdated things like how professional a site looks, whether there are spelling errors and how many ads there are, or if you dwell too much on the importance of the domain name. His SIFT approach does look really interesting, and it is fantastic that he has provided all the materials under Creative Commons (we’re big fans of that here!) – but it is largely asking students to do the same thing as the CRAAP test, just presented in a different way. What are they looking for under “Investigate the source” if it isn’t some sense of:

- Is this Current?

- Is it Relevant to my inquiry?

- Does it seem to be reasonably Accurate? (How do I know? Have I checked it against other sources? Does anything about the claims feel odd?)

- Does the writer/site have any Authority to make this claim? (How do I know? Have I checked their general reputation, not just the qualifications they claim to have?)

- What is the Purpose of this story? (What are they trying to convince me of and why? Everyone is selling something!)

Having said that, I will be having a good look at the Check please site, because I think there is a lot there that could be really helpful (even if I choose to combine it with CRAAP). Thanks Elizabeth!

I think Mike is absolutely right that it is easy for students to get overloaded, and as such I tend to go for a ‘light touch CRAAP test’. Rather than mechanically go through the motions of the whole list, I would encourage students to focus on the area they think is most important for that source. As Barbara says, Authority and Purpose are pretty much non-negotiable. Currency and Relevance are very quick (if it isn’t relevant, there is no point continuing with the rest!), and Accuracy is often tied up with Authority.

There are many ways to teach source evaluation, and all of them have advantages and disadvantages, but what we are actually teaching students is a sense of healthy suspicion. Does it seem too good to be true? Does something seem a bit odd? Does it tie up with what you knew already? Then giving them the tools to follow up their suspicions. It doesn’t have to be very time-consuming if you start with reasonably reputable sources – but they need guidance on where to find reasonably reputable sources and what they ‘feel ‘ like. And we need to talk honestly and non-judgementally about Wikipedia. What is it good for? What isn’t it good for? Why do you need to be careful with it? (This is part of a presentation we use on this topic occasionally).

In the article Mike says (emphasis added):

“The CRAAP approach assumes that students need to learn, for example, that authority on a subject matters, that funding matters, that conflicts of interest matter, and asserts if we train students in a twenty minute catechism that reviews these issues each time they’ll make better decisions. The reality is checklist or no checklist we know most of these issues when we see them. Most people get intuitively that Russian state media is not be the best source on whether Russia was involved with the downing of MH17. The difference between the professional fact-checker and the student is a set of digital habits that quickly reveal that RT is a Russian propaganda arm, or that a particular naturopathic cancer center has a reputation for quackery. The gap isn’t the understanding, it’s the missing context.”

I do actually disagree with him here (and this may be because I am mostly working with younger students). Many of our students don’t have a good understanding of authority (which is why Wikipedia can be a problem – because they don’t really understand, or sometimes care, what they are dealing with). They also aren’t great at realising that all of the sources that they read have an agenda of some kind and that they need to be alert to that. I’m not convinced that many untrained high school students would automatically have a problem with a Russian state media source giving information about the downing of MH17. Particularly if they were new to the story and didn’t really understand the agendas involved. Yes, the gap is the missing context, but that context needs to be taught and the CRAAP test is one way to do that (as is SIFT). And it doesn’t have to be taught as a 20 minute checklist.

In that sense (and I don’t find myself saying this very often!) I am with Professor E. D. Hirsch (a well-known opponent of Inquiry Learning) – we cannot treat children as if they have the same level of social and cultural literacy that adults have. Where Professor Hirsch and I deviate, as far as I understand it, is that he feels that this means that inquiry is an unsuitable way for young people to acquire new understanding, where as I believe that it means that we need to give them tools and support to do what an expert would do automatically. We need to give them a scaffolding that can drop away once they fully grasp the underlying skills and concepts.

I have used this presentation and accompanying resources to teach the CRAAP test to both Year 9 and Year 12. An important point about it is that the Breitbart article on which it is based is a very well-written, well-presented article – and they have largely not heard of Breitbart (a highly questionable, very right-wing US media outlet). The key here is getting them to spend a few minutes looking for information about the organisation and the article outside the original site (a vital point that I picked up very strongly from John Royce’s article) before reading too deeply. The other key point is to give them some useful tools to help them to check the leanings of unknown sites (such as https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/ ). Those of us from the UK, for example, know that The Daily Mail is a right wing tabloid, prone to hyperbole, often inaccurate and downright misleading, whereas The Times is a broadsheet that is right-centre in tone but largely accurate in its reporting. Do our students know that? Or do they just think that we would prefer them to read the Times because the Mail is a bit gossipy and more ‘fun’? Do many adults realise quite how misleading the Mail can be, and how dangerous a news diet based a single media source is, particularly one like this? It is a national paper, after all. We need to be giving students practical tools like Media bias/Fact check, and keeping pace with change. This is a good tool now – just as domain names were a good tool 15 years ago. In 10 years time, I’m sure we will need different tools to support something like the CRAAP test. But that doesn’t mean the test itself is a bad one.

As Stephanie says – let’s teach them not to judge a book by its cover. But then we do need to give them some other criteria to judge it by, given the whole point is that their ‘gut feel’ is not yet well-developed.

P.S 1: after looking at the Breitbart article with Year 12, one student was quite aggrieved that it got such a low score. He said “But they’ve worked so hard to make it look good. Don’t they deserve some credit for that?”. Perhaps that is an argument for doing away with the scoring aspect of CRAAP. We aren’t giving the sites a mark for effort – we’re looking at whether they are suitable sources to use in our work!

P.S. 2: the Times/Mail discussion is another powerful argument for promoting reading and literacy (digital or otherwise) in our schools generally. One of the startling facts that Alice Visser-Furay highlighted in her excellent presentation for CILIP SLG in July 2020 (also available from her website, Reading for Pleasure and Progress) was that the average reading age of an article in the Sun (UK tabloid) was 8 years old, while for the Guardian (UK broadsheet) it was 14 years old. There is a social imperative to make sure that the next generation of the voting public have the literacy skills (and inclination) to get their news from reputable sources.

26th March 2021 at 3:43 pm #40831I’ve read with interest what you have all said on the CRAAP test and it will certainly be helpful as I plan for an upcoming teaching session with year 7 boys, which will be on the evaluation of sources. I particularly like the idea of a ‘light touch CRAAP test’ as the year 7 groups I’ve taught previously, have struggled with the CRAAP exercise I’ve done with them in the past. I’ll think through how I might do this differently.

I think what Barbara had to say on p.56 on the need for students to be taught have to evaluate the different formats information is available in is really interesting. I don’t know the answer here, but it’s certainly a really interesting thing to think about. When I was thinking about this, my recent experience in self-testing for Covid-19 came to mind. When I read through the instruction booklet, I was slightly overwhelmed as there’s a lot of information in it and it’s a bit overwhelming. I was chatting about it with my library colleague and she recommended that I watch the video. So I did and the video really helped me to understand what I needed to do. What’s interesting and having reflecting on the process, now that I’ve done it a few times, is that neither format of information was sufficient on it’s own. For example, the video doesn’t demonstrate exactly where the tonsils are, you also need the picture in the booklet.. Applying this learning to my own teaching, I would want to say to students, that they should use a variety of formats in their research. A video certainly does make something more accessible, but you also need information in other formats to really get a full understanding.

Thank you so much for writing such interesting responses, I’ve enjoyed reading them and I look forward to the conversation we’ll have on Sunday afternoon. I sometimes feel like I should be doing more as a school librarian, but I was so encouraged when I received these words from my line manager this week; “Well done, too, on the way you have continued to raise the profile of the Library with staff and pupils, by highlighting how it can contribute to the education we offer in so many ways. I appreciate that it is a challenging time for librarians, but you are setting an excellent example for what can be done despite the restrictions we continue to face.” These words apply to all of us, we are doing a good job 🙂

26th March 2021 at 3:45 pm #40834The latest posts by Elizabeth, Stephanie, and Jenny have pushed me to think more deeply about evaluating online sources. I agree that we need to teach students how to evaluate the sources/websites they find and giving them specific criteria to consider is at least a starting point. I agree that laboring through all of the criteria for each source is time-consuming and perhaps counter productive (because students won’t continue with that beyond an academic requirement). But I also think there is value to giving students enough specific and detailed practice in using each of the criteria that they become habits of mind. I totally agree with Jenny that our goal is to make source evaluation second nature, so that students quickly decide which criteria are important to assess for each source and they can use specific strategies to make their own decisions about the value of a source.

Then I started thinking about the criteria themselves and ended up with some additional considerations that I am wondering about. When we check for authority (Jenny provided the important insight to look outside of the original source), I think students may need to check the authority of both the publisher/organization and the author (if named separately). For the publisher, students should consider point of view/bias and reputation. Both are very difficult to assess. For the author, students need to consider the authority in context. I will never forget working with students to determine authority and we discovered that the author had a PhD, but in a completely unrelated area to the topic at hand. This “authority” was actually offering his personal opinion rather than authoritative evidence about the topic.

The authority issue becomes even more complicated when an author or presenter is an authority on the topic, but offers information that is contrary to the bias of the publisher and therefore should not be dismissed as representing the publisher’s point of view. That happens occasionally in the US when a television network host interviews someone live (e.g., when Fox News, a very conservative news outlet, interviewed Dr. Fauci, a recognized expert in COVID). It’s hard for anyone to sort through the conflicting information to figure out what’s true (or mostly true). I think that’s why so many of us succumb to confirmation bias.

I loved what Stephanie said about judging a book by its cover. We all tend to do that, I think. Even librarians have figured out that, if we want our administrators to read our library news and reports, we need to package the information visually or in an easy-to-read format, because they are too busy to read in-depth narratives. Infographics have become increasingly popular as a way for librarians to communicate with administrators, parents, and even teachers. I think this is why I am convinced that visual literacy must be a part of our teaching, because all students are inundated with visual information and they are absorbing subliminal messages.

Your conversation has also caused me to think more deeply about purpose. I am not sure about how to teach students to determine a source’s purpose. How can we help students decide if the purpose is to educate, persuade, criticize, entertain, or editorialize? Once they decide, how do we help them determine the impact on the credibility and usefulness of the information? And, along those lines, how do we help students recognize their own purpose and how that impacts what information they gather and how they interpret it?

The focus on students’ purpose brings me to my next consideration about evaluating information. Much of our conversation has been about evaluating sources. After students have done that, they then need to evaluate and interpret the information within the sources. I think that’s when deep reading skills become so important. Especially in the digital world of live presentations, podcasts, and television broadcasts, students need to recognize that even reliable, authoritative sources might “publish” a segment that includes misinformation, biased opinion, or strategic gaps in information. Whew! It seems exhausting. This is where Jenny’s wisdom gives us a way forward: “what we are actually teaching students is a sense of healthy suspicion.”

We’ll talk more in a couple of days. I’m looking forward to it.

26th March 2021 at 8:37 pm #40937Ahead of the Q&A on Sunday, and opportunity to reflect on the discussion so far.

It appears to me that for many school librarians there is a paradigm shift that needs to precede the paradigm shift that Barbara refers to in her chapter, which is to recognize that the school library has a clearly defined pedagogical programme, and that the impact, and therefore value, of the school library is directly linked to the quality of this programme. This pedagogical programme is outlined in Chapter 5 of the IFLA School Library Guidelines, which draws on over 60 years of international research into the effectiveness of school libraries. For reference, the 5 core instructional activities of the professional school librarian are: (1) Literacy and reading promotion; (2) Media and information literacy instruction, which may be within an (3) Inquiry-based learning model; (4) Technology integration; (5) Professional development for teachers.

As a consequence of the school library’s pedagogical programme and the school librarian’s core instructional activities, the school librarian is a teacher, regardless of whether they recognize it or not, which is part of this first paradigm shift.

The question is, a teacher of what?

This question gives rise to the second paradigm shift.

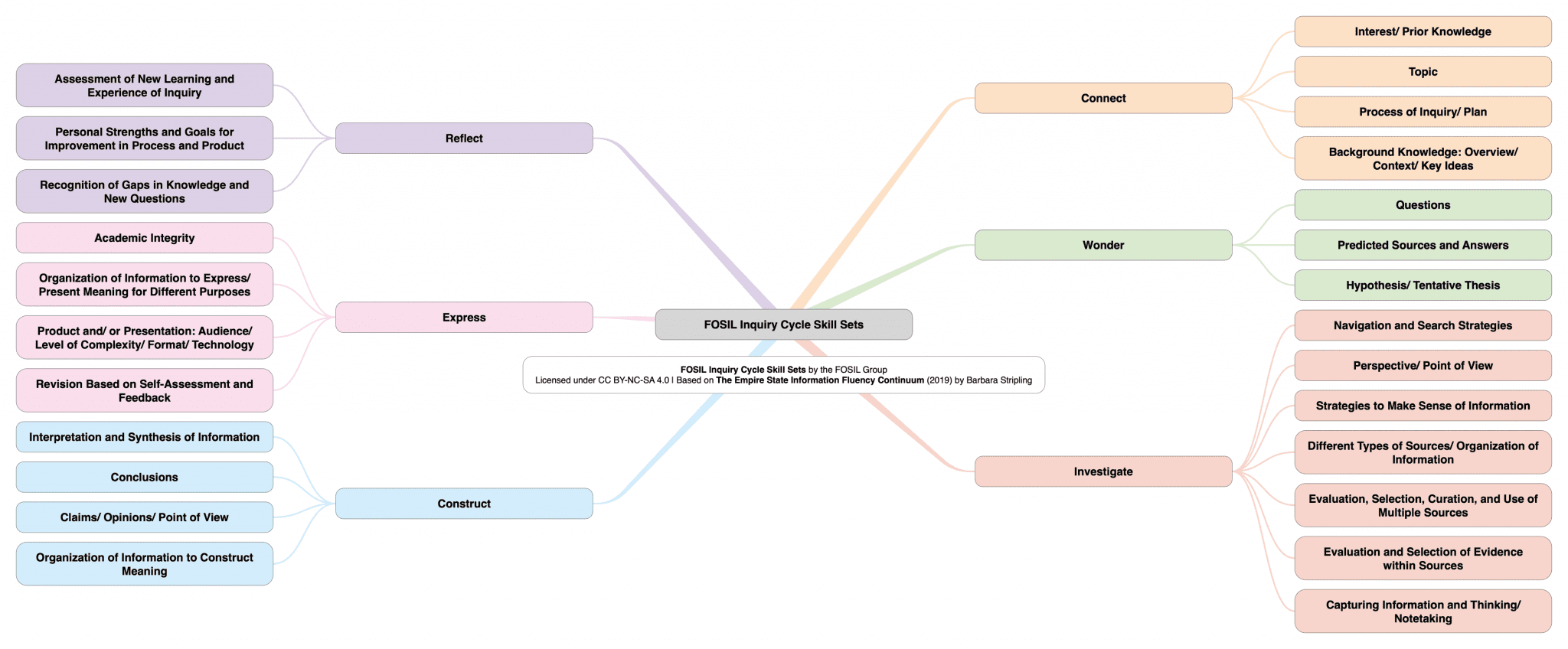

In E&L Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry, Barbara makes the point that John “Dewey’s recognition of the need for both content and skills provided solid justification for the role of a school librarian as a teacher of sense-making skills”. This contours the second paradigm shift for me, which is a shift from a narrow concern with sources of information – mainly the information search, evaluation and retrieval aspects of Investigate, and the academic integrity aspect of Express (see Figure 1 below) – to a broad concern with the full process of learning from information in the context of subject area teaching. This process of learning – building knowledge and understanding/ making sense – from information is the school librarian’s subject specialism, and the basis for collaboration with classroom teachers/ colleagues.

This takes time, and is more or less difficult depending on our particular circumstances, but take courage – I have been wrestling with this on some level since becoming a school librarian in 2003, and Barbara for far longer, yet here we all are. It is worth reiterating Barbara’s point above that she has learned the most about the skills she needs to teach students by engaging in inquiry as a learner herself and reflecting on the process, and my point above that the tag line for FOSIL, reflecting my insight into this process, is Learning by finding out for yourself (not by yourself, which suggests minimal or no guidance and/ or interventions).

To understand why this paradigm shift matters, recall our expanded definition of inquiry, which is “a stance of being open to wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community“. Evidence of our collective failure to effectively educate to this end is overwhelming, hence the urgent necessity for this second paradigm shift, which, as Barbara points out in her chapter, is still underway. Furthermore, a paradigm shift is always traumatic, but the second one will be doubly so for those colleagues who have not yet recognized the signs of the first one.

While our primary concern is with inquiry learning in the context of subject area teaching, the IB document Ideal libraries: A guide for schools that I referred to above reminds us that “libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin” (p. 9). This means that the nature of the library as a learning space, which is different to the classroom as a learning space, will provide opportunities for both formal and informal interventions in student inquiry that the classroom does not – which is why, “ideally, the librarian is trained in many ways of creating conditions for inquiry within and beyond the classroom” (p. 9) – but always in our role as teachers of sense-making skills.

Then, we get to what I think is a third paradigm shift, which is the shift from a predominantly print to a predominantly digital environment. Marshall McLuhan’s insight that the medium is the message – or massage, in that the medium works us over completely (1996, p. 26) – is helpful, because while our concern remains understanding what is said, the digital medium through which it is said problematizes understanding in a paradigmatically different way. This means that we are needing to simultaneously deal with two problems: the age-old problem of building knowledge and understanding from information, mainly though reading (see Reading for Inquiry Learning, particularly from this post onward); the new problem of the digital medium, which McLuhan, quoting A. N. Whitehead (pp. 6-7), warns is a major advance in civilization, and that “the major advances in civilization are processes which all but wreck the societies in which they occur” (consider, for example the 25 March 2021 US congressional hearing into the role of social media in promoting extremism and misinformation, with specific reference to the 6 January 2021 insurrection at the Capitol – Google, Facebook Twitter grilled in US on fake news).

This – and for other excellent reasons raised in this discussion, particularly related to the physiology of reading – means that at times we will need to critically embrace the digital medium, while at other times we will need to actively resist it.

This also overlaps with the discussion about CRAAP (or other) testing.

Inquiry, as we have said, is a stance, or attitude, of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic learning process. This dynamic inquiry learning process proceeds through distinct but interrelated stages, each of which is enabled by concrete skills that need to be developed systematically and progressively, and between the library and the classroom, over the course of a student’s time at school.

(It is worth reminding ourselves that FOSIL, based as it is on the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, is all of these things – a robust framework/ model of the inquiry process, a highly coherent PK-12 (Reception-Year 13) framework/ continuum of concrete inquiry learning skills, and a growing collection of specialized graphic organizers that can be adopted/ adapted for instructional and/ or formative assessment purposes – and more – the FOSIL Group is a growing international community of inquiry that has grown up around FOSIL, but is not limited to FOSIL, and one that benefits from active collaboration with Barbara.)

Even at the Skill Set level, or what the ESIFC terms Indicators, a concern with “bullshit and the art of crap-detection” (Postman, 1967) is evident, particularly in the Investigate and Connect stages (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: FOSIL Cycle Skill Sets

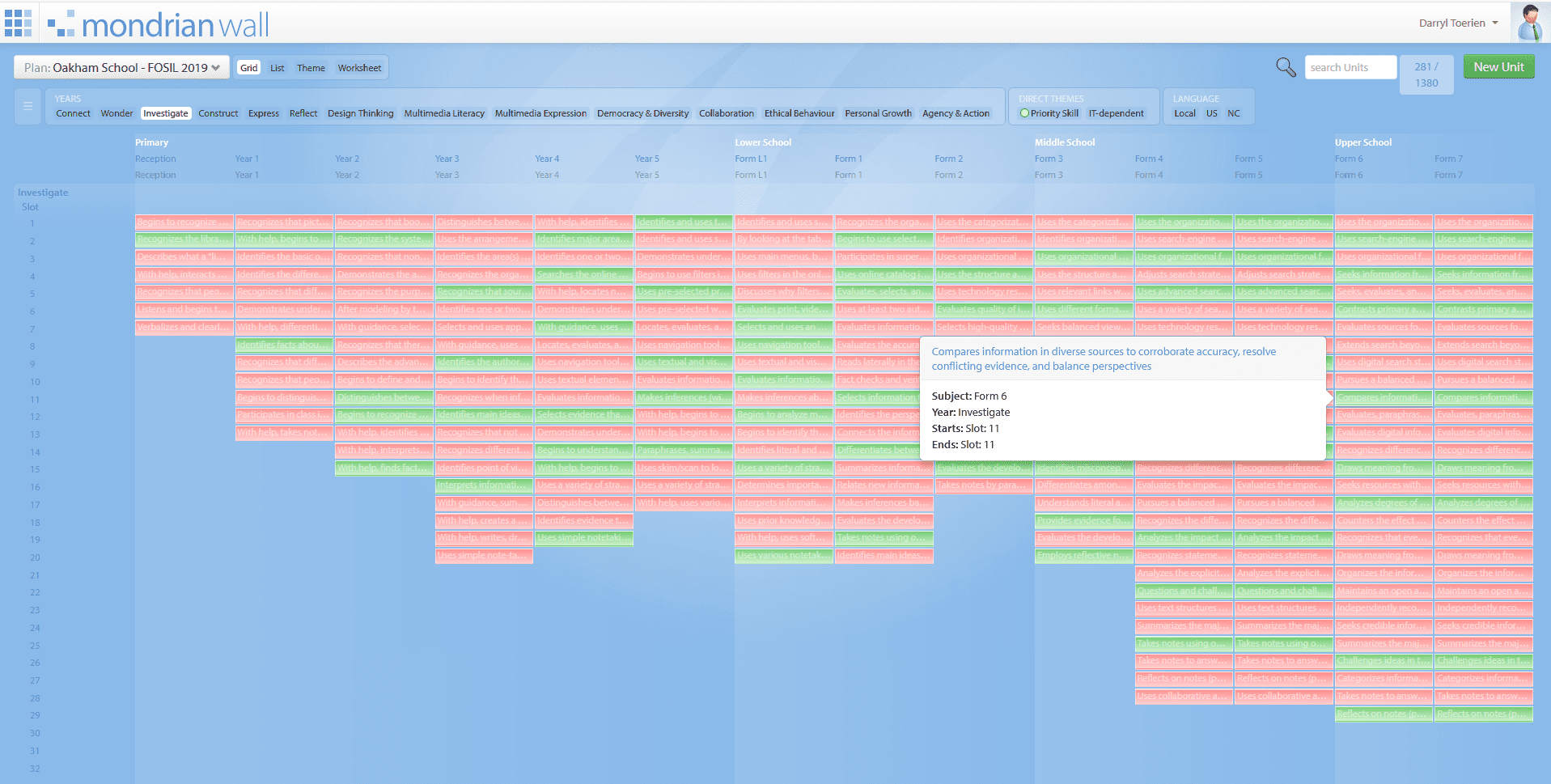

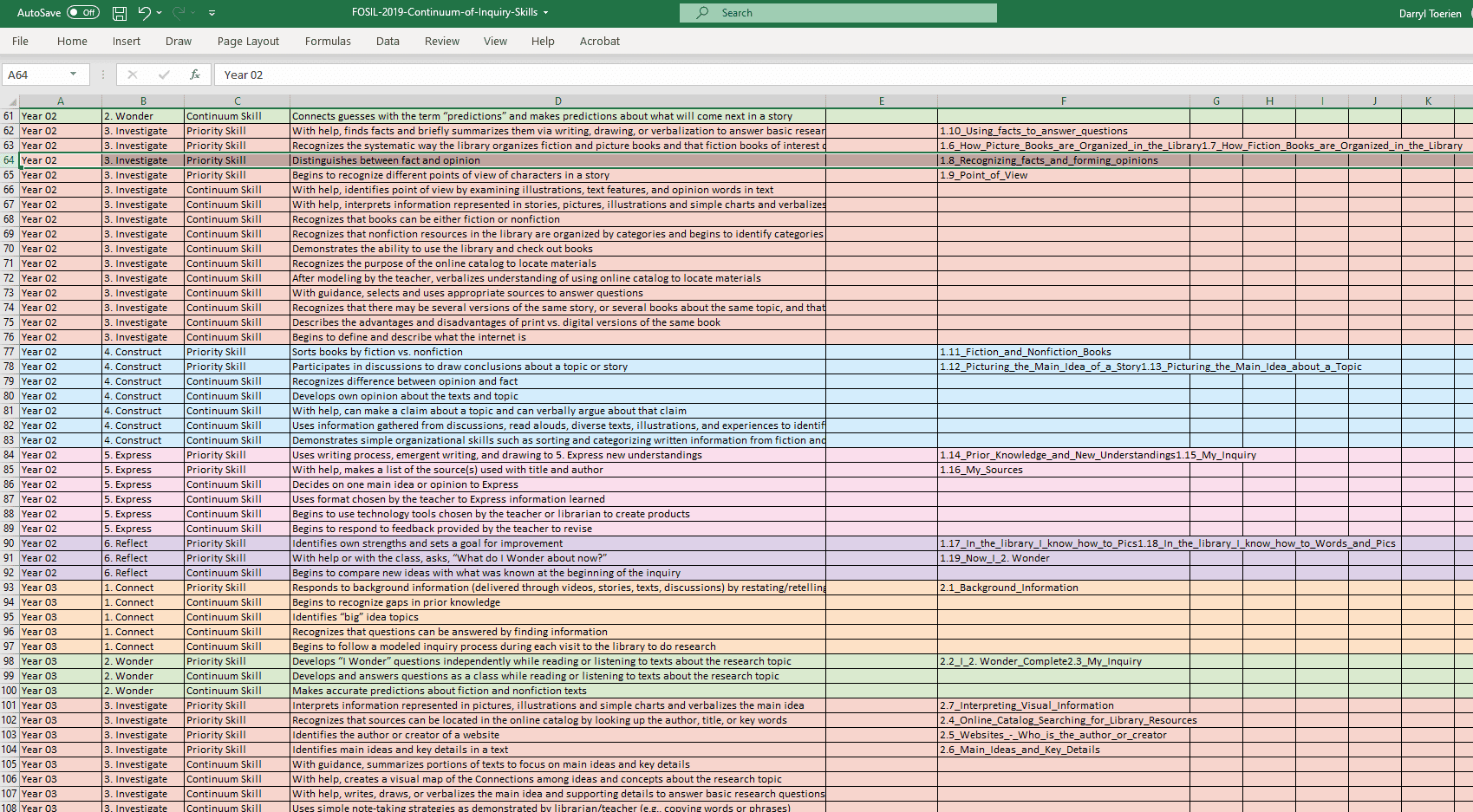

At the Skill level, this stance, or attitude, towards “bullshit” gives rise to a developmental continuum of concrete skills that enable increasingly sophisticated “crap-detection” (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 below, for example).

At the Skill level, this stance, or attitude, towards “bullshit” gives rise to a developmental continuum of concrete skills that enable increasingly sophisticated “crap-detection” (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 below, for example).Figure 2: Priority Skills (Green) and Continuum Skills (Red) in the Investigate Stage

Figure 3: Snapshot of Priority and Continuum Skills for All Years and Stages

It is important to point out that, like with the CRAAP test, this is not a crushing list of skills to teach, but rather a developmental description of the skill sets that children need if they are to be be effectively equipped for the lifelong task of learning for themselves – hence the identification of priority skills, and even those are up for thoughtful debate in our local contexts.

This is what I find is missing from most discussions about the inability of students to discern misinformation, disinformation and malinformation, especially from the perspective of university, which is the recognition that our system of schooling is perfectly designed to achieve the results that it is getting – without a systematic and progressive approach to developing the skills that enable the process of effectively learning from information within the context of content area teaching, we bear responsibility for their inability to do so outside of or beyond school. This, then, is much more than the failure of a tool, or even a failure in our approach to using that tool.

Thanks, Helen, for the encouragement and also looking forward to Sunday.

References

- IBO. (2018). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organisation.

- McLuhan, M., Fiore, Q., & Agel, J. (1996). The medium is the massage. London: Penguin Books.

- Postman, N. (1969, November 28). Bullshit and the Art of Crap-Detection. Retrieved from Escaping from Bullshit: http://ditext.com/wordpress/2018/10/08/neil-postman-bullshit-and-the-art-of-crap-detection/

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.