Integrating FOSIL with MYP ATLs

Home › Forums › Skills, skills frameworks and stages in the FOSIL Cycle › Integrating FOSIL with MYP ATLs

- This topic has 22 replies, 5 voices, and was last updated 10 months, 4 weeks ago by

Ruth.

Ruth.

-

AuthorPosts

-

24th May 2019 at 10:42 am #1369

Oakham School became a candidate school for the IB Middle Years Program in September 2018, which was an exciting step because it confirmed and cemented the School’s philosophical commitment to move towards a more inquiry-based educational paradigm. There is a lot of new terminology to get to grips with in a move like this, such as: Key and Related Concepts; Global Contexts; Factual, Conceptual and Debatable Questions; and Approaches to Learning (ATL). If you are not careful it is easy for the jargon and the paperwork to become overwhelming and mask the important shift in educational thinking that needs to take place.

Lucy, our Lower and Middle School Curriculum Librarian, has done an amazing job in getting to grips with the language and supporting some of the early adopters through all phases of their first MYP inquiries (see, for example, Year 7 English Inquiry and Year 7 History Inquiry). One question that has come up frequently from teaching staff is “How does this integrate with FOSIL?”. Our challenge is to demonstrate how FOSIL, which is a powerful tool for understanding and supporting the inquiry process, is fundamental to effective support for MYP inquiries rather than a competing (and complicating) model. It isn’t a ‘bolt-on’ initiative – a set of boxes to tick after you have planned your inquiry to show that you are ‘doing FOSIL’ as well as MYP – but rather a tool that can help everyone to plan and support inquiries more effectively and efficiently and, critically, to get to grips with some of the MYP terminology.

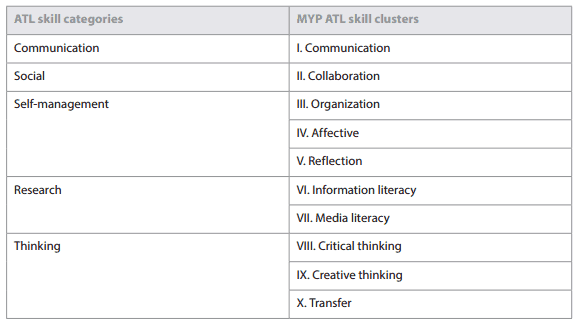

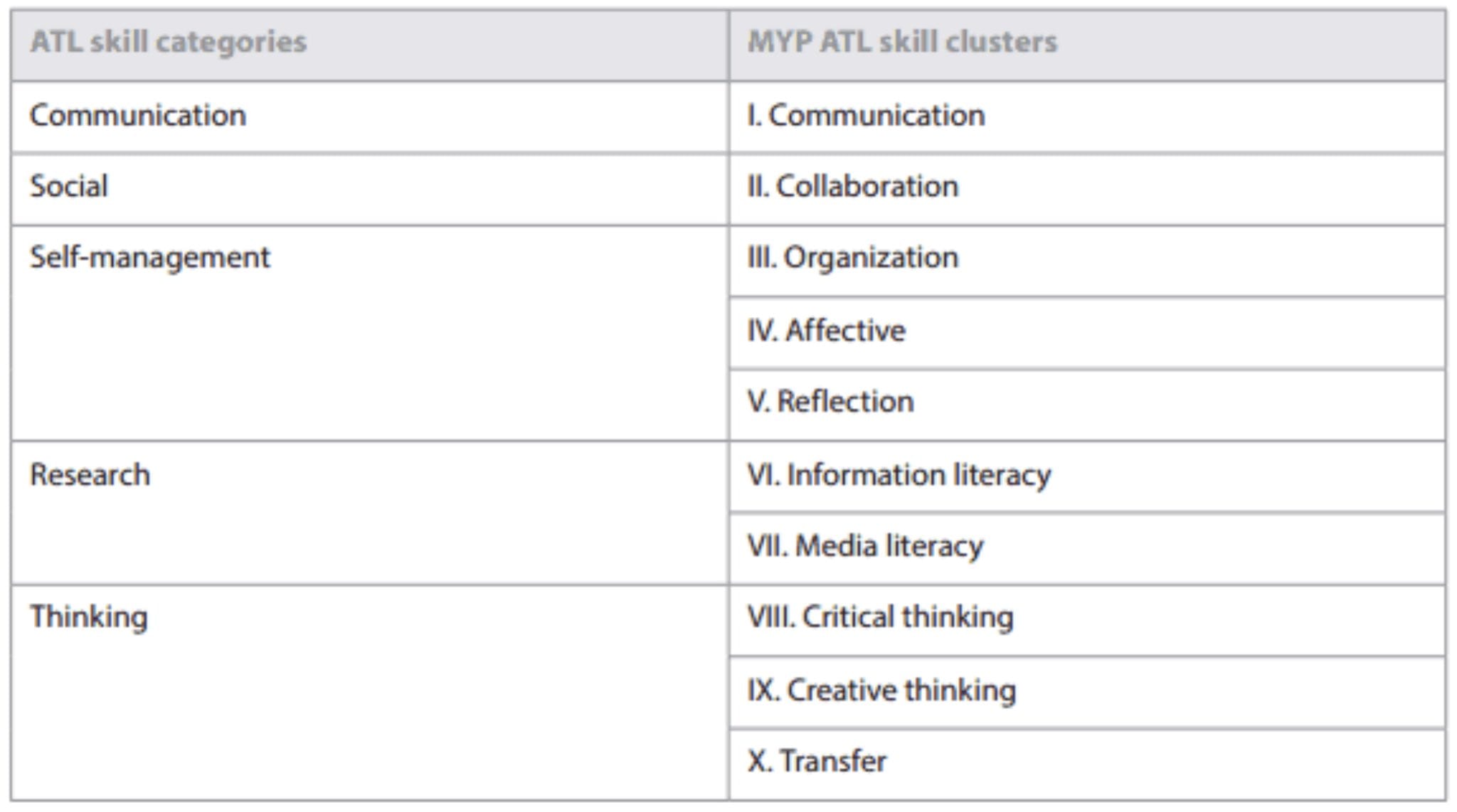

In helping teachers to fill in the MYP planning paperwork, we found that one aspect that was particularly difficult was selecting which ATLs to focus on during each unit – whether an inquiry or inquiry-led. This is not surprising given there are more than 130 to choose from, divided into 5 categories, and 10 clusters within those categories.

24th May 2019 at 10:55 am #1370

24th May 2019 at 10:55 am #1370In order to help teachers to get to grips with the new skills more easily, we needed to align them with the FOSIL skills. We had to demonstrate that these frameworks are not just two different versions of the same thing, but that they can work together effectively to support learning and make planning easier. The FOSIL skills are generally more concrete, they show how students progress as they move through the school, and have linked resources (that students are already used to) showing what that skill might look like in the classroom.

We were aware that there was a HODs’ horizontal curriculum planning day coming up on June 11th and were keen to put something together before then to help to demonstrate how the two frameworks could be meaningfully integrated to make their jobs easier. The main challenges we faced were:

- Some of the ATL skills encompassed a vast range of skills in a single sentence, so we mapped several different rows of FOSIL skills to the same ATL skill.

- Because of the way they were arranged, several skills were repeated worded in slightly different ways in different categories, so we mapped several different ATL skills to the same row of FOSIL skills.

- Some ATLs relate to social development and have no specific analogue in the FOSIL framework, either because they are developed over the course of a whole inquiry (e.g. Demonstrate persistence and perseverance) or because they do not relate to inquiry skills at all (e.g. “Practice strategies to prevent and eliminate bullying”). We decided to categorize these as either “whole inquiry” or “PSHE” skills.

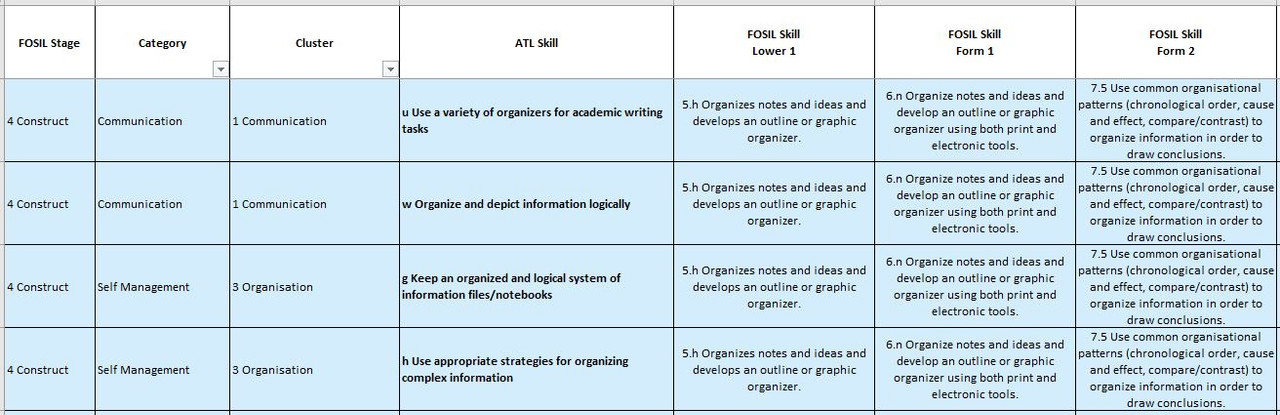

Chris, our Head of Student Research, began the process by identifying which stage of inquiry he thought each ATL skill was most suited to, Lucy continued it by matching individual ATL skills to specific FOSIL skills, and I pulled everything together into a spreadsheet (see images, above). My first task was to rearrange the FOSIL skills into separate rows showing how a single skill progresses up the school, something we have been meaning to do for a while, then I could match each ATL to one or more rows.

Although still a work in progress, we presented the spreadsheet to the Director of IB, MYP Co-ordinator and Deputy Head (Academic) on Monday (May 20th), along with examples of a concrete set of FOSIL resources that had been used in inquiries to support particular FOSIL skills – and therefore could now be matched to ATLs. They were excited enough by the prospect of a resource that could help HODs to link the ATL skills and FOSIL – and, perhaps more importantly for them, to help HODs to understand what the ATL skills might look like in the classroom – that they have invited Darryl, our Head of Library, to lead a session at the upcoming HODs’ horizontal curriculum planning day on June 11th. This is an exciting and important opportunity, but doesn’t give us long to complete, polish and refine the integration so that it is ready for use!

We know that several of you will be on the same journey and would love to hear where you have got to and what you have learnt so far.

25th January 2021 at 6:34 am #35026Hi Jenny,

This is where I was hoping to end up, with a document detailing how FOSIL allows the ATLS to be taught and measured without lots of extra work on behalf of the teachers. I am planning on a handbook with examples for many of the skill at each level.

However, I fear that without the kind of Librarian resource that Oakham have it may never come to pass. This is a huge ask but I was wondering whether you are planning to make the entire spreadsheet available here? I do recognise that you and your colleagues have put a vast amount of work into this and that I would need to look at it in light of our curriculum, school environment and student intake but it would be such a huge boost to FOSIL in our school.

At the least, thanks for showing it can be achieved,

Ruth

26th January 2021 at 9:37 am #35093Hello, Ruth.

I have picked this project up and am, coincidentally, working on it this week.

The intention for the FOSIL Group was always for us to achieve together what would not be possible for us to achieve on our own. Jenny will upload the template with the footer that you asked about after EE Supervisor INSET this afternoon (yesterday proved too ambitious), and I will ask her how much more there is in the spreadsheet and whether it is worth sharing.

I have steered the project in a different direction (see below), and hope to finish by the end of the week.

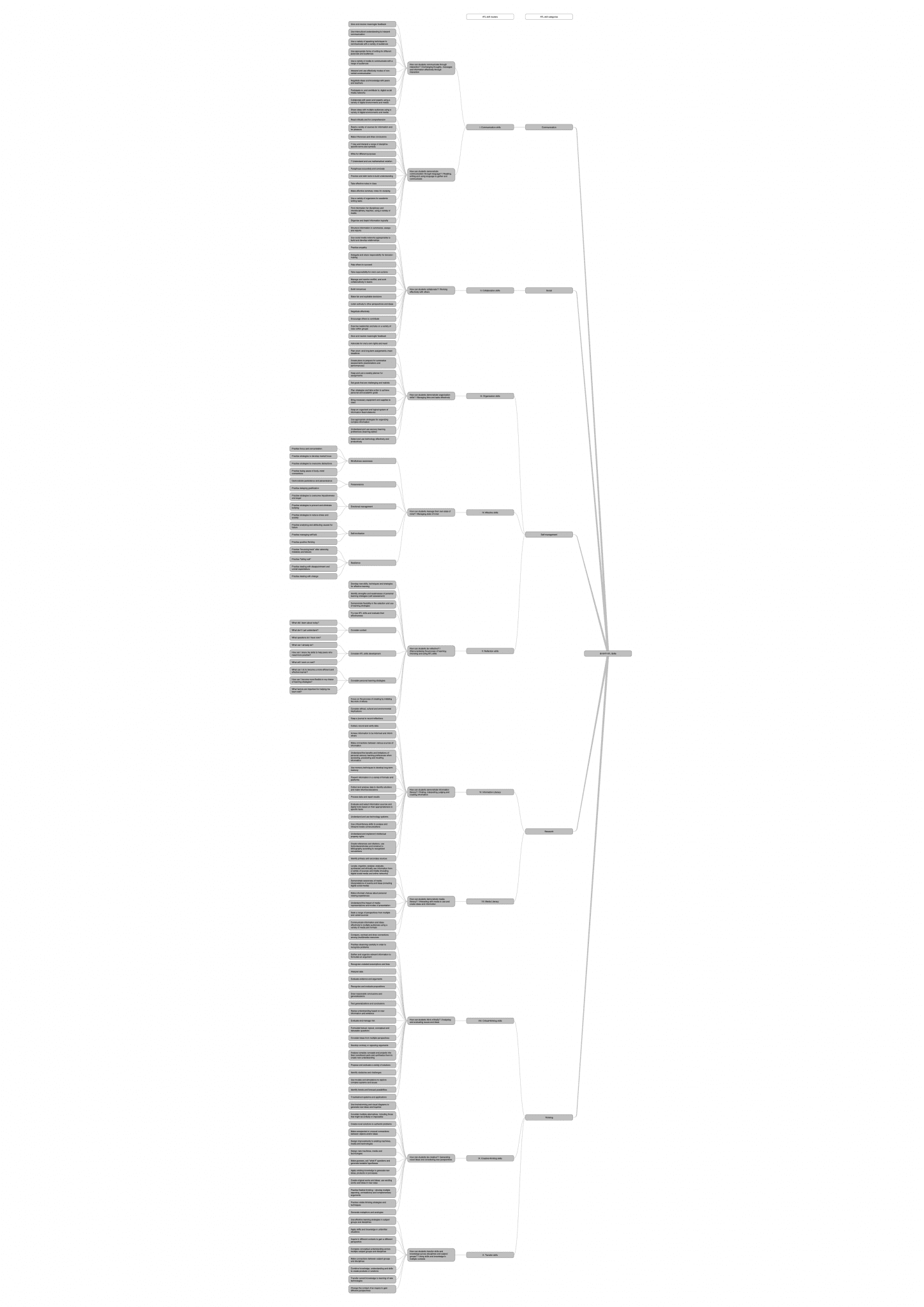

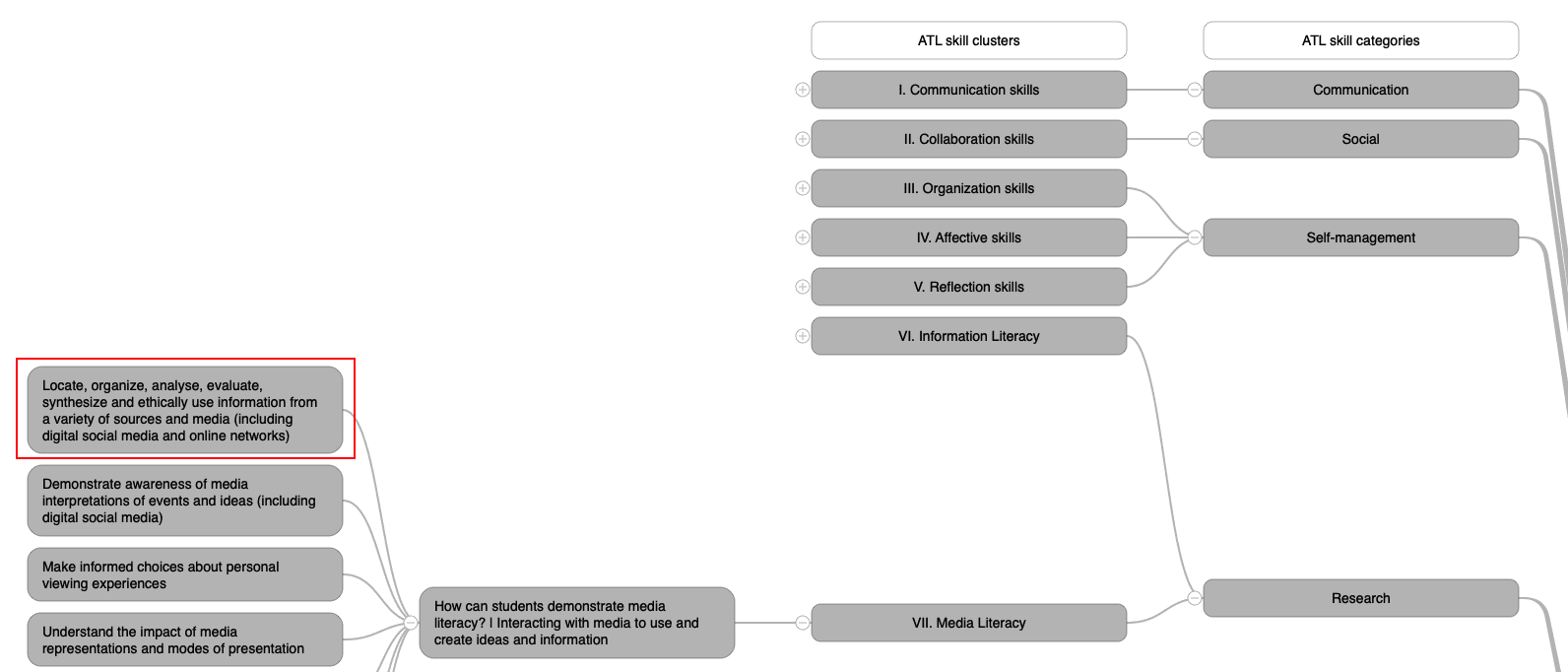

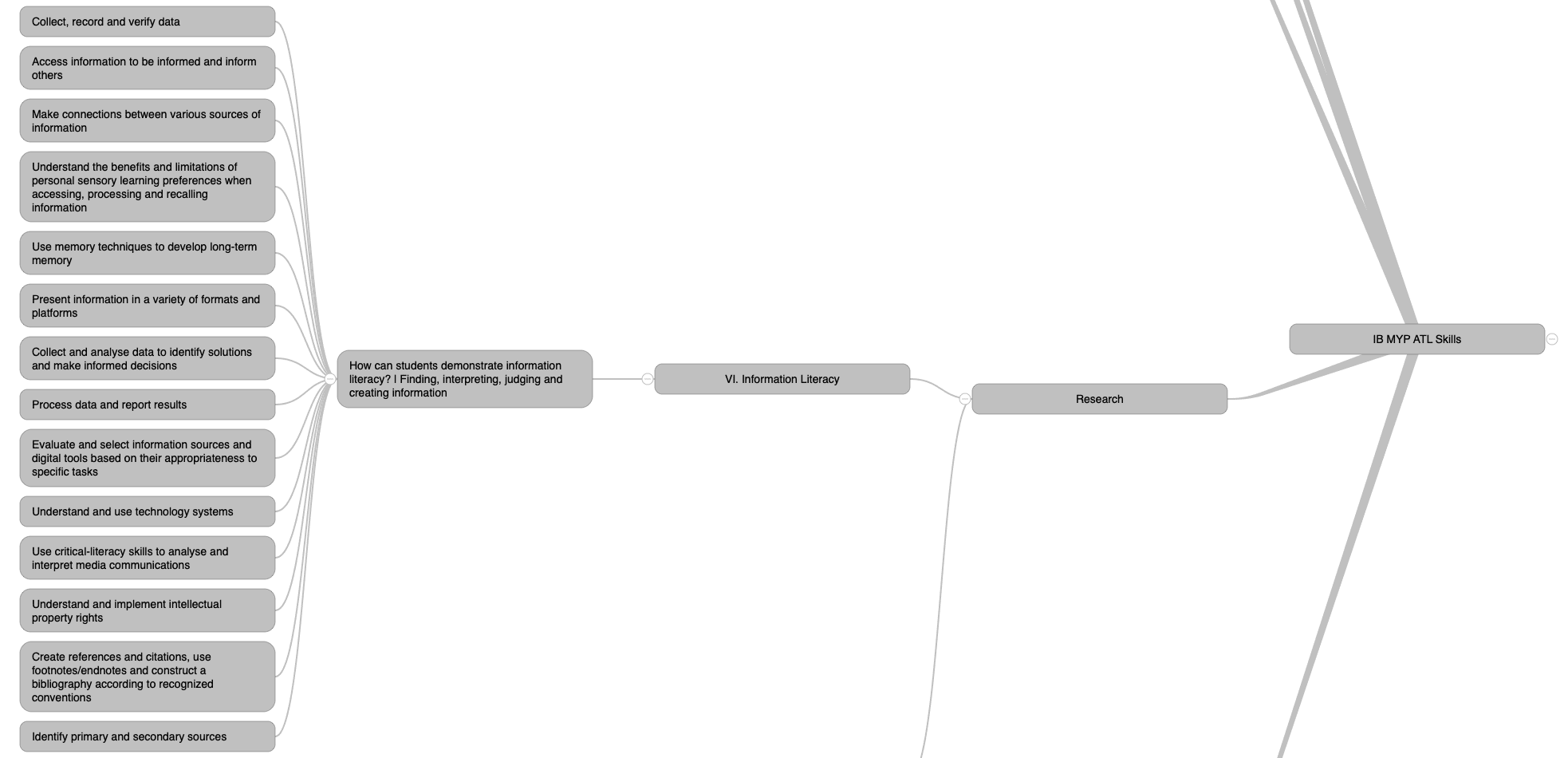

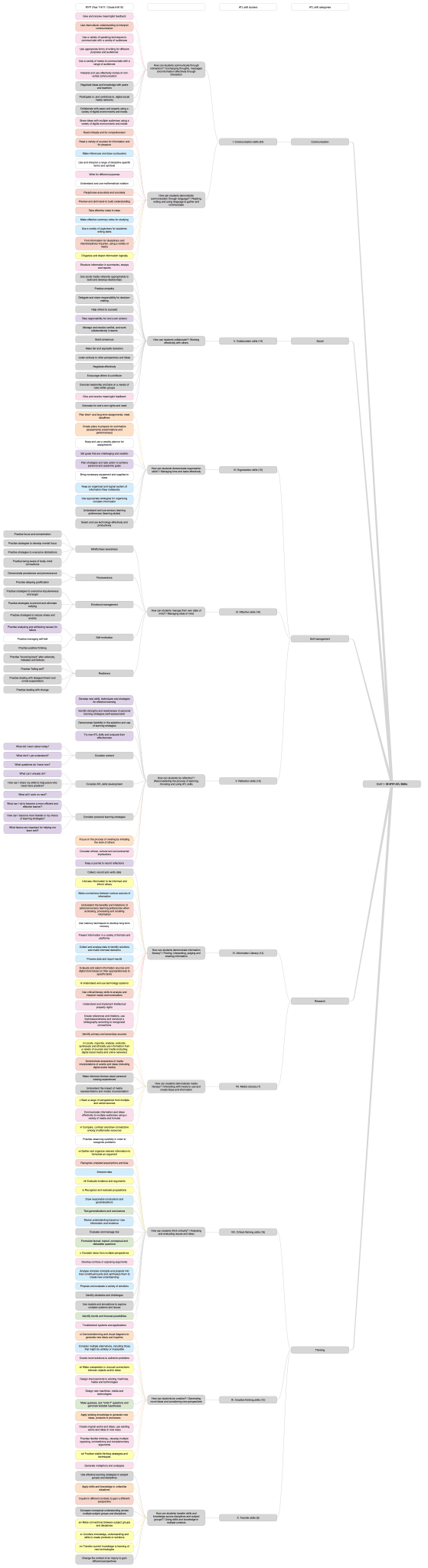

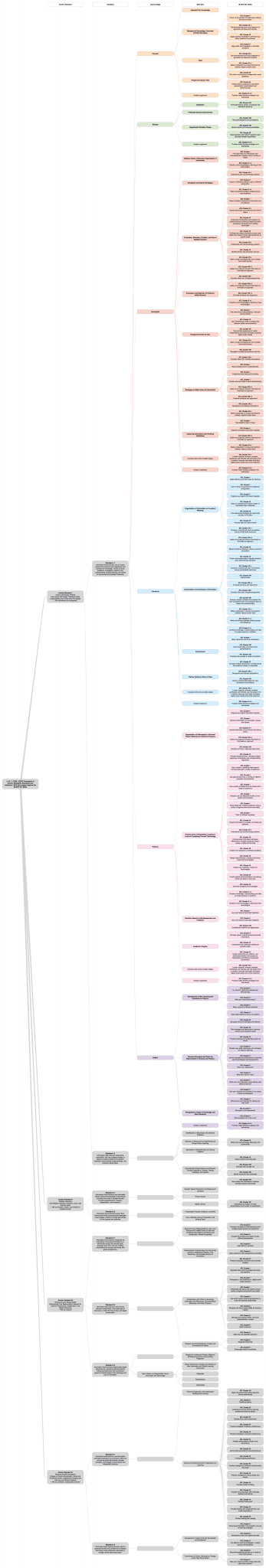

I have created a branching map of the ATL Skill categories, clusters and skills, as well as a branching map of the FOSIL [and ESIFC] skill sets.

This week we will map the ATL skills across to the FOSIL [and ESIFC] skill sets. I am hopeful that all of the ATL clusters and categories will have skills in the FOSIL skill sets, because this will go a long way towards making sense of the ATL skills within a logical process, as well as making them more manageable (the 140 listed in the documentation are indicative rather than imperative).

More to follow later this week.

ATL Skill categories, clusters and skills (download as A3 poster here – the map is very large, but legible at 400% zoom)

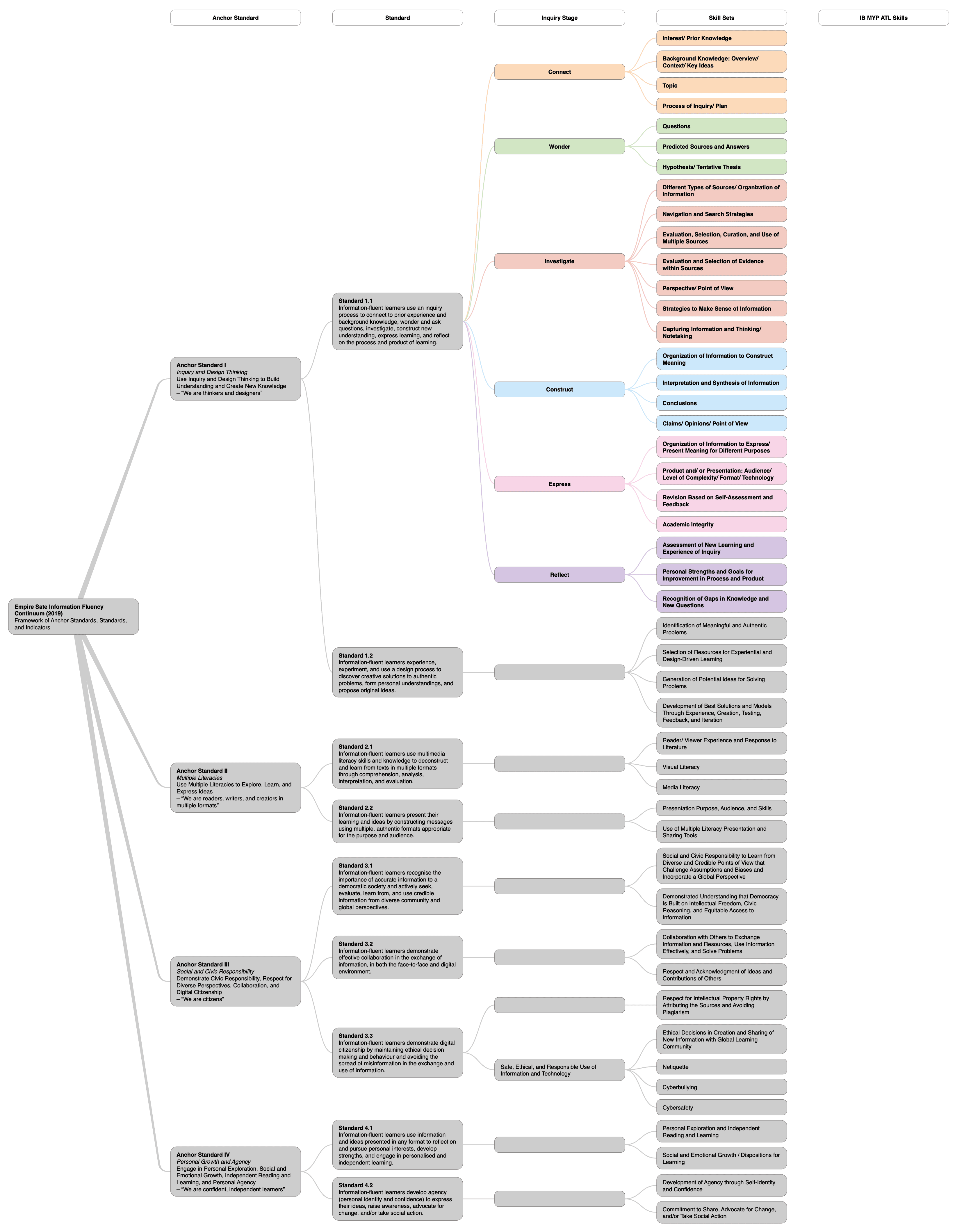

FOSIL and ESIFC Skill sets (download as A3 poster here – the map is large, but legible at 140% zoom)

27th January 2021 at 12:40 pm #35161

27th January 2021 at 12:40 pm #35161Goodness me, this is a huge amount to think about. I’m both impressed and envious of what you have achieved so far.

I could really do with a course / workshop / real live conversation about this so I can get the thinking clear in my head. I wonder if there are any other IB Librarians who would be interested in working this through together. If anyone is keen maybe we can carve out some time together?

27th January 2021 at 4:09 pm #35184Hi Ruth,

I’ve attached the spreadsheet for what it’s worth – although I think the direction Darryl has taken now will ultimately prove both more fruitful and easier to explain to classroom colleagues. I must confess that I haven’t done anything on this for about a year because aspects of my job changed and I was pulled in a different direction (which is why Darryl has picked it up) so it is not as complete as I would like it to be. We are having another push to look into this more seriously now though, for various reasons, so your timing is excellent. Darryl’s also been having some fascinating and very productive conversations with Barbara Stripling, who developed the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, on which FOSIL is based, which have reinforced to him how much thought and expertise went into the original formulation of the skills, and how much they have to offer in integrating the ATLs meaningfully into inquiry.

Conversations are always fruitful – and the last year has shown how much is possible with online meetings – so it would be great to get together at some point soon. As you say – anyone else out there interested in joining the conversation?

[Note: my spreadsheet is a bit crude. A database would be better for this really, and in the longer term we are hoping to use our Mondrian Wall curriculum mapping software. The two sheets in my spreadsheet are not ‘connected’, they are just the same data sorted in different ways. If you make changes on one sheet, delete the other, make a new copy and resort it using the dropdown menus at the top.]

Attachments:

28th January 2021 at 11:52 am #35242Ok, so I think, having looked at these I do now understand the relationship between them. I think the work you are planning will effectively join the ESIFC on the left across the void to the ATLs on the right. Is that correct?

If so I think my next step would be to look at the curriculum plans across the school and see where the skills can best be introduced and reinforced across MYP. This would create another 3 maps that sit behind this and show its practical implementation in years 7, 8 and 9 (we only run the 3 year MYP) Is that what you are planning?

I think that I may need to have done that before I am able to get the staff on board. Clearly, I would only be able to suggest ideas and any detailed lesson documents or workbooks would be my next step when teachers have seen the benefit and we can collaborate.

28th January 2021 at 1:01 pm #35247Across the void – exactly!

I’ll share more on this tomorrow.

2nd February 2021 at 1:29 pm #35520Apologies for the delay, but I am working around some constraints in the mapping software.

From the perspective of FOSIL, the Approaches to learning (ATL) skills present 3 problems.

The first is that the ATL skills are grouped logically into categories and clusters (see Figure 1 below), but not logically according to stages in the inquiry process, such as FOSIL (see Figure 2 below and attached as an A3 poster).

Figure 1: IB MYP ATL Skill Categories and Clusters

Figure 2: FOSIL Inquiry Stages and Skill Sets

This is odd, because “inquiry, as a curriculum stance, pervades all [IB] Programmes” (Tilke, 2011, p. 5). This then creates a practical problem for teachers/ librarians, because they either need to figure out which stage of the inquiry process individual ATL skills logically belong to, or they need to figure out which ATL skills fit logically into each of the stages of the inquiry process. Given that some ATL skills from all the clusters / categories need to be taught explicitly, the gap between the logic of the ATL skill clusters/ categories and that of the inquiry process practically ensures that these inquiry-learning skills will not be developed systematically and progressively within the inquiry process.

It is worth pausing to clear up a misconception at this point. Inquiry is an approach to learning (hence the MYP Approaches to learning) and teaching (hence the MYP Approaches to teaching). FOSIL is both a model/ framework of the inquiry process and a framework/ continuum of the inquiry-learning skills that enable the stages of the inquiry process. FOSIL is, therefore, an approach to learning and teaching, and so encompasses all of the ATL skill clusters / categories. The misconception is that inquiry, and by association FOSIL, is the same as research, and is, therefore, reduced to the Research ATL skill category, which only involves the Information Literacy and Media Literacy ATL skill clusters. The IB recognizes this – Ideal libraries: a guide for school (IBO, 2018, p. 9), citing Callison (2015) and Levitov (2016), states that “inquiry is more expansive than research, and facilitating it requires expertise beyond research methods”. This echoes the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015), which identify developing media and information literacy (MIL) skills within the inquiry process as core instructional activities of the school librarian. From the perspective of FOSIL, it is more accurate to think of research as Investigate, with elements of Express and Construct.

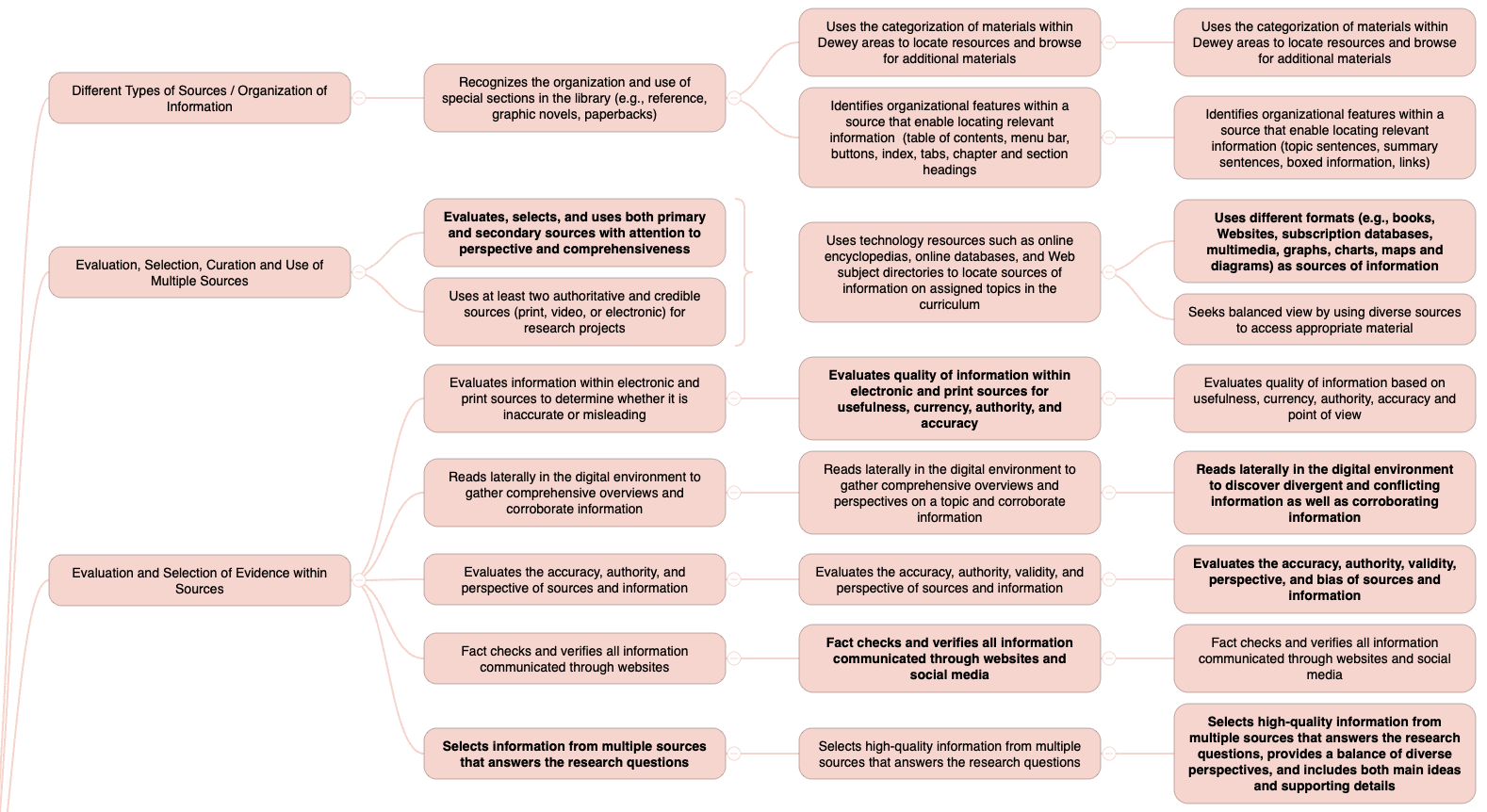

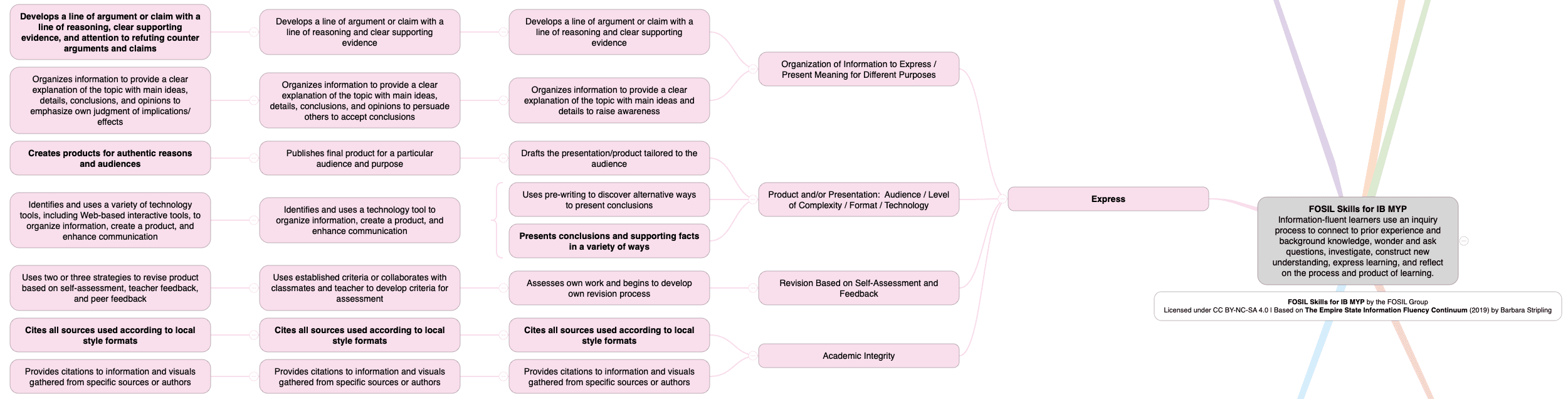

Secondly, the 140 ATL skills listed in the IB documentation is not meant to be prescriptive, and schools may use their own framework of skills provided that they cover all of the ATL skill clusters/ categories. This is a tall order, though, and it is more likely that schools will view the list of 140 ATL skills as canonical and end up treating them as peripheral, rather than integral, to the inquiry process. By contrast, the inquiry-learning skills that make up the continuum of inquiry-learning skills that FOSIL is based on (see Figure 3 and 4 below, for example, both of which are attached as A3 posters) are integral to the inquiry process. This continuum of inquiry-learning skills – stretching from PK (Reception) to Grade 12 (Year 13) – was developed by Barbara Stripling in 2009, endorsed by New York State in 2012 as the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, and reimagined in 2019 “to adapt to the changing information, education, and technology environments, as well as the increasing diversity in our student populations”.

Figure 3: FOSIL Inquiry Stages, Skill Sets and Priority Skills for MYP (Grades 6-8 / Years 7-9)

Figure 4: FOSIL Inquiry Stages, Skill Sets and Continuum Skills with Priority Skills for MYP (Grades 6-8 / Years 7-9)

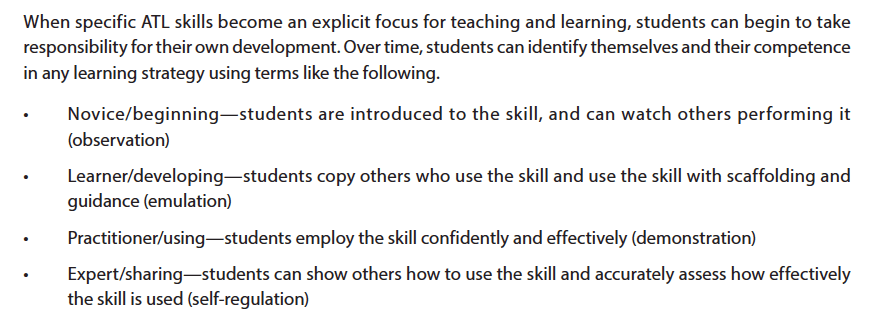

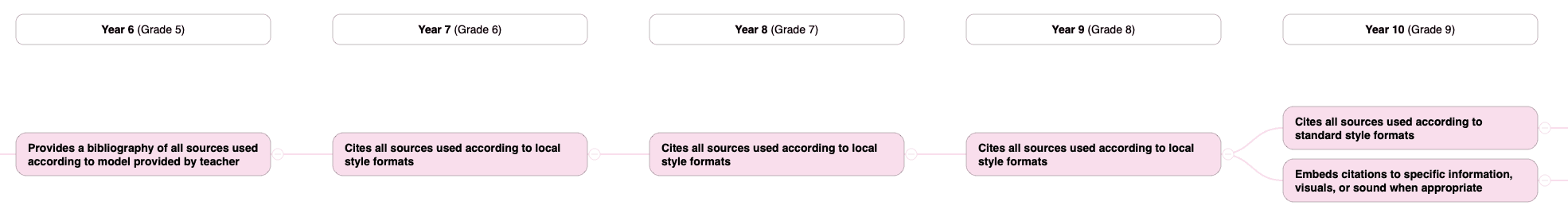

Thirdly, there is the question of proficiency / competence. MYP: From principles into practice (IBO, 2017, p. 107) states:

While this fine for assessing competence / proficiency in any given ATL at any given point, it presents practical difficulties for the teaching of the ATL skills in a systematic and progressive way. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, some of the ATL skills are actually skill sets, or complexes of skills (see, for example, Figures 5 and 6 below). Secondly, there is no sense of how a given ATL skill, or complex of skills, develops over the course of the MYP (see, for example, Figures 5 and 6 below), or even over the course of a single year.

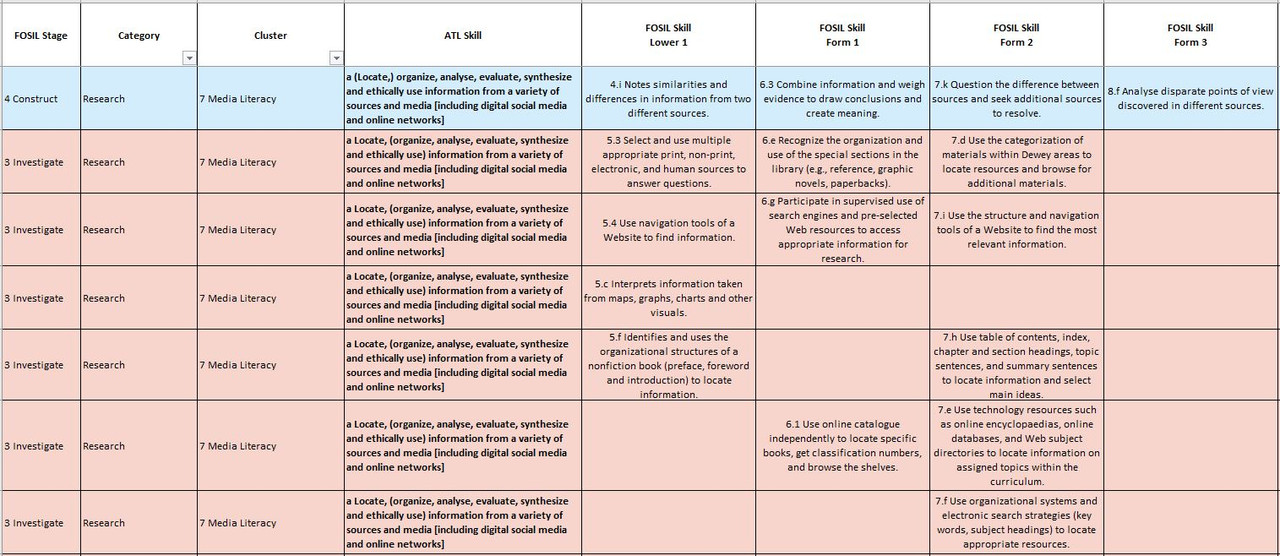

For example, the ‘single’ ATL skill of “locating, organizing, analysing, evaluating, synthesizing and ethically using information from a variety of sources and media (including digital social media and online networks)” (see Figure 5 below) is actually a [very] complex of skills/ skill sets, which are mainly located in part of the Investigate stage of FOSIL (see Figure 6 below), although there are also elements of Construct and Express included for good measure!

Figure 5: Example of a Complex ATL Skill

Figure 6: Partially Unpacking and Progressively Developing a Complex ATL Skill in FOSIL

I will develop this post further with a practical example drawn from our Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project and Year 9 Individual Project (which are instructive for Grade 6 (Year 7) and Grade 11 (Year 12), and the mapping of the MYP ATL skills to the FOSIL skill sets.

—

References

- Callison, D. (2015). The evolution of inquiry : controlled, guided, modeled, and free. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

- IBO. (2017). MYP: From principles into practice Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organization.

- IBO. (2018). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organization.

- Levitov, D. (2016). School Libraries, Librarians, and Inquiry Learning. Teacher Librarian, 28-35.

- Tilke, A. (2011). The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program and the School Library: Inquiry-Based Education. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

2nd February 2021 at 2:54 pm #35528Thanks Darryl,

That is a brilliant articulation of the issue I had been grappling with but had not yet managed to articulate. Having read this summary of this issues I can now see clearly why I had had such difficulty matching the ATLs to FOSIL and then thinking about how this can inform the practical implementation of inquiry learning. I fear I may be working towards an achievable goal?

3rd February 2021 at 11:49 am #35588Thanks – it took me long enough 🙂

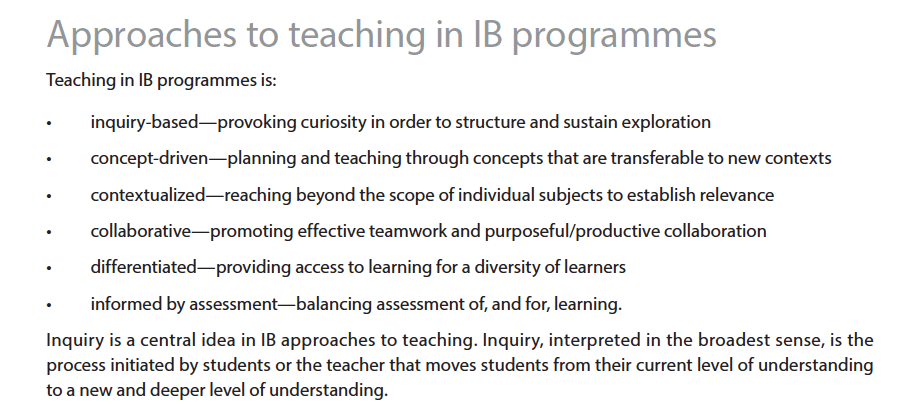

Not only do I think this is an achievable goal, but I also think that it is vital that we pursue this goal. The key to achieving this goal will be to provide confidence-inspiring evidence that approaching the ATL skills through FOSIL not only satisfies the IB’s requirements for the explicit teaching of ATL skills, but actually benefits the teaching and learning of the ATL skills, as well as the Approaches to teaching more broadly (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Approaches to teaching

The immediate value of FOSIL (or any other sound model of the inquiry process) is that it makes the stages of the inquiry process explicit. MYP: From principles into practice makes reference to the inquiry process and the inquiry cycle, but does not, as far as I can tell, explicitly model this process/ cycle. The added value of FOSIL, as discussed in my post above, then, is that it is both a sound instructional model of the inquiry process/ cycle and a continuum of the inquiry-learning skills that enable each of the stages of the process/ cycle – see E&L Memo 1 | Learning to know and understand through inquiry by Barbara Stripling and Reflecting on E&L Memo 1 with Barbara Stripling for insight into the development of the inquiry model and continuum of inquiry-learning skills that FOSIL is based on.

It is important to be clear that approaching the ATL skills through FOSIL does not mean that all teaching and learning needs to be a full inquiry that involves all of the stages of the FOSIL inquiry process – a misconception that arises from a lack of understanding that inquiry is both a process and a stance – but it is difficult to imagine any teaching and learning that does not involve skill sets/ skills from one or more of the stages in the FOSIL inquiry process. This is entirely consistent with the view of MYP: From principles into practice that “not all approaches to teaching in the MYP will take place in an inquiry setting”, and “can include lectures, demonstrations, memorization and individual practice” (p. 74).

I have not had time today to include a practical example, but will aim to do so tomorrow.

By way of encouragement from MYP: From principles into practice (p. 64):

Schools can use this list [of ATL skills] to build their own frameworks for developing students who are empowered as self-directed learners, and teachers in all subject groups can draw from these skills to identify approaches to learning that students will develop in MYP units.

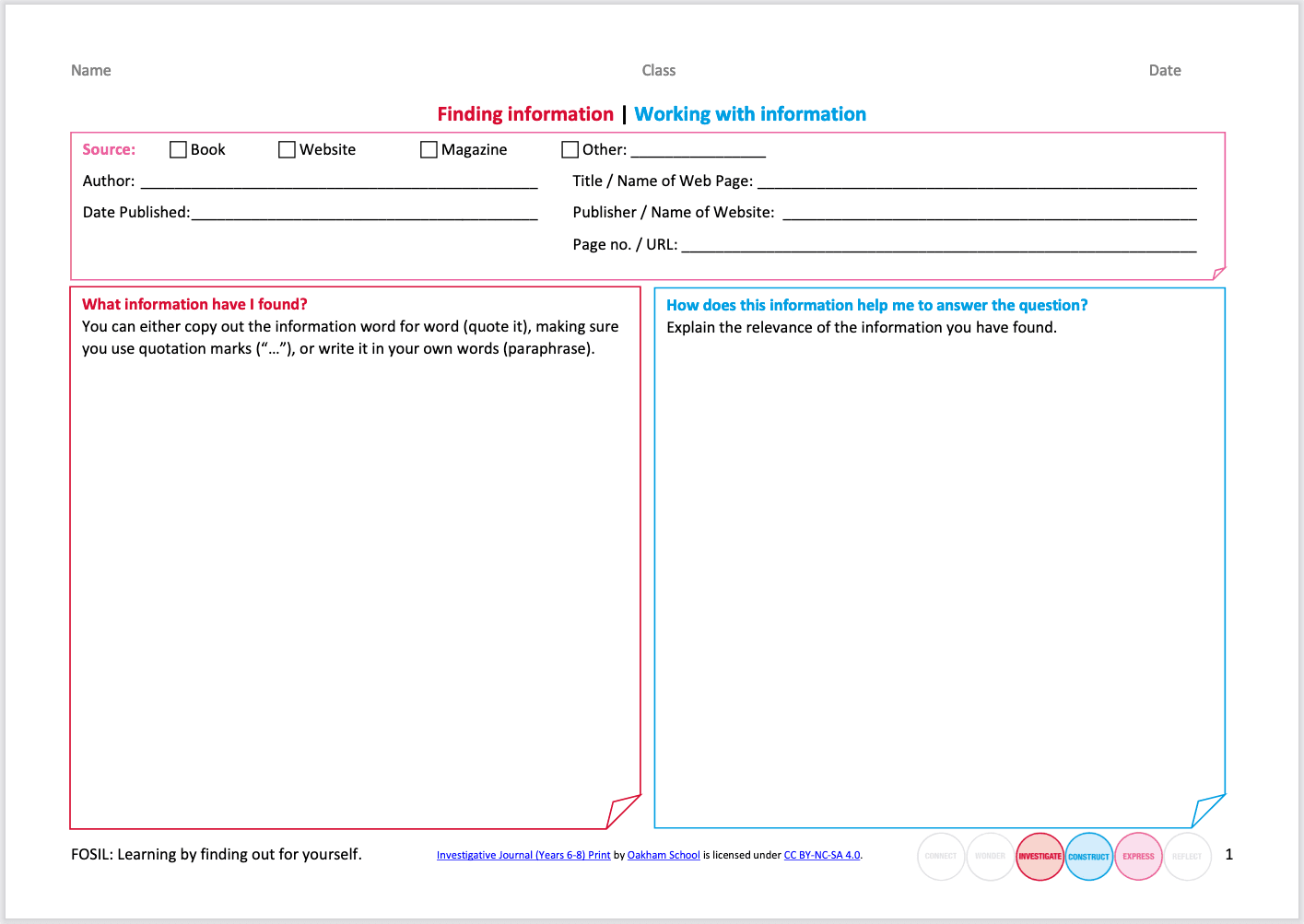

7th February 2021 at 12:18 pm #35784I will use citing sources to illustrate various aspects of the discussion above.

Citing is 1 of 14 ATL skills located within the Information Literacy cluster in the Research Category (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Citing as an ATL Skill

By contrast, citing constitutes the Academic Integrity skill set in FOSIL, which is located in the Express stage (see Figure 2 below), and which, regardless of the terminology used, is consistent with instructional information literacy models as well as instructional models that develop information literacy skills within the inquiry process.

Figure 2: Citing as a FOSIL Skill

This matters from an instructional point of view, because in addition to teaching students how to cite (which requires mainly technical and mechanical competence, but also academic competence), we also need to teach them when to cite, which is when they are sharing their knowledge and understanding with reference to the sources of information that their knowledge and understanding is built from (which requires mainly academic competence). This reflects the broader problem with the ATL skills, which is that the logic of the categories and clusters is not the logic of the learning process, which in the case of the MYP is an inquiry-based learning process.

Using Year 9 (Grade 8) as an example, which is instructive for Year 7 (Grade 6) and Year 12 (Grade 11), a number of practical difficulties emerge.

Year 9 (Grade 8) is the final year of our 3-year MYP. As explained in the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project Topic, approximately half of the students joining us in Year 9 are new to the school, with the other half joining us from our Lower School. (In Year 7 (Grade 6), the overwhelming majority of student are new to the school, while in Year 12 (Grade 11) a significant minority of students are new to the school, mainly to do the IB Diploma Programme.) From the perspective of the school library, information literacy skills instruction has benefitted from a process approach since the early 1980s, although the broader shift towards a specifically inquiry-process approach, and hence the development of inquiry-learning skills within the inquiry process, has been underway since the early 1960s. In the absence of a national continuum of inquiry-learning skills – which, in the case of the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum that FOSIL is based on, includes literacy, inquiry, critical thinking and technology skills, involves both the cognitive and affective domains, and addresses cognitive, emotional and social development – students entering the school in year 9 do so with varying degrees of competence in citing their sources. Since the development of FOSIL in 2011, all students entering Year 9 from our Lower School will be increasingly competent in citing their sources, and ought to describe themselves as Practitioner at the very least (see Figure 3 below), given that we have had 2 years to teach them to cite their sources, and they ought to have had 2 years to practise citing their sources across all subject groups.

Figure 3: ATL Skill Competence Levels

By contrast, the overwhelming majority of students who are new to the school in Year 9 would describe themselves Novice. This situation presents us with 2 instructional problems, which are mirrored in Year 7 and Year 12, which are (1) how to effectively develop the level of competence of all students in a certain skill when for some/ many that skill is a new skill, and (2) how to effectively teach that skill so that all students describe themselves as at least Practitioner. From the perspective of the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project, students encounter the skill of citing their sources during the process of an inquiry, which means that they record the details of their sources mainly during the Investigate stage of the inquiry, and then cite their sources during the Express stage. This means that the skill is taught and practised as part of the inquiry process, which is a learning process. This also means that the skill is encountered as a means to an end – embedded in learning – rather than an end in itself. The fact that the skill is a means to an end also means that those students who are already Practitioners can simply use the skill of citing in the course of their inquiry, while those students who are Novices can benefit from greater instructional help, either from the teacher or, preferably, other students who are Experts. However, from an instructional point of view, I would expect all students to emerge from the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project as at least Practitioners of the skill of citing their sources, because this is the level that I would be teaching this skill at.

Now, if we had an equivalent to the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project In Year 7, then I would expect all Year 7 students to emerge from the Year 7 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project as at least Practitioners of the skill of citing their sources, because this is the level that I would be teaching this skill at. This raises another aspect of the problem with the progression of skills within the ATL. Within the FOSIL continuum of skills, the skill of citing sources progresses developmentally (see Figure 4 below).

Figure 4: The Development of Citing in the FOSIL Continuum

It is worth noting that while citing as a technical term first appears in Year 7, making the distinction between something that I have created and something that someone else has created, which is the foundation that academic integrity rests on, is first taught in Reception (Pre-K). Our local style format, or house style, is based on [a simplified] APA, which is what we teach and use in Years 6, 7 and 8. We actually make the shift to full APA as our standard style format in Year 9, because we have the opportunity to do so through the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project – and not in Year 10 (Grade 9), when the focus of teaching and learning has almost entirely shifted to preparation for the Year 11 (Grade 10) public GCSE public examination – and it proved to be developmentally appropriate to do so.

By contrast, there is no sense of how the ATL skill of “creating references and citations, using footnotes/endnotes and constructing a bibliography according to recognized conventions” develops over the course of either the 3-year or 5-year MYP.

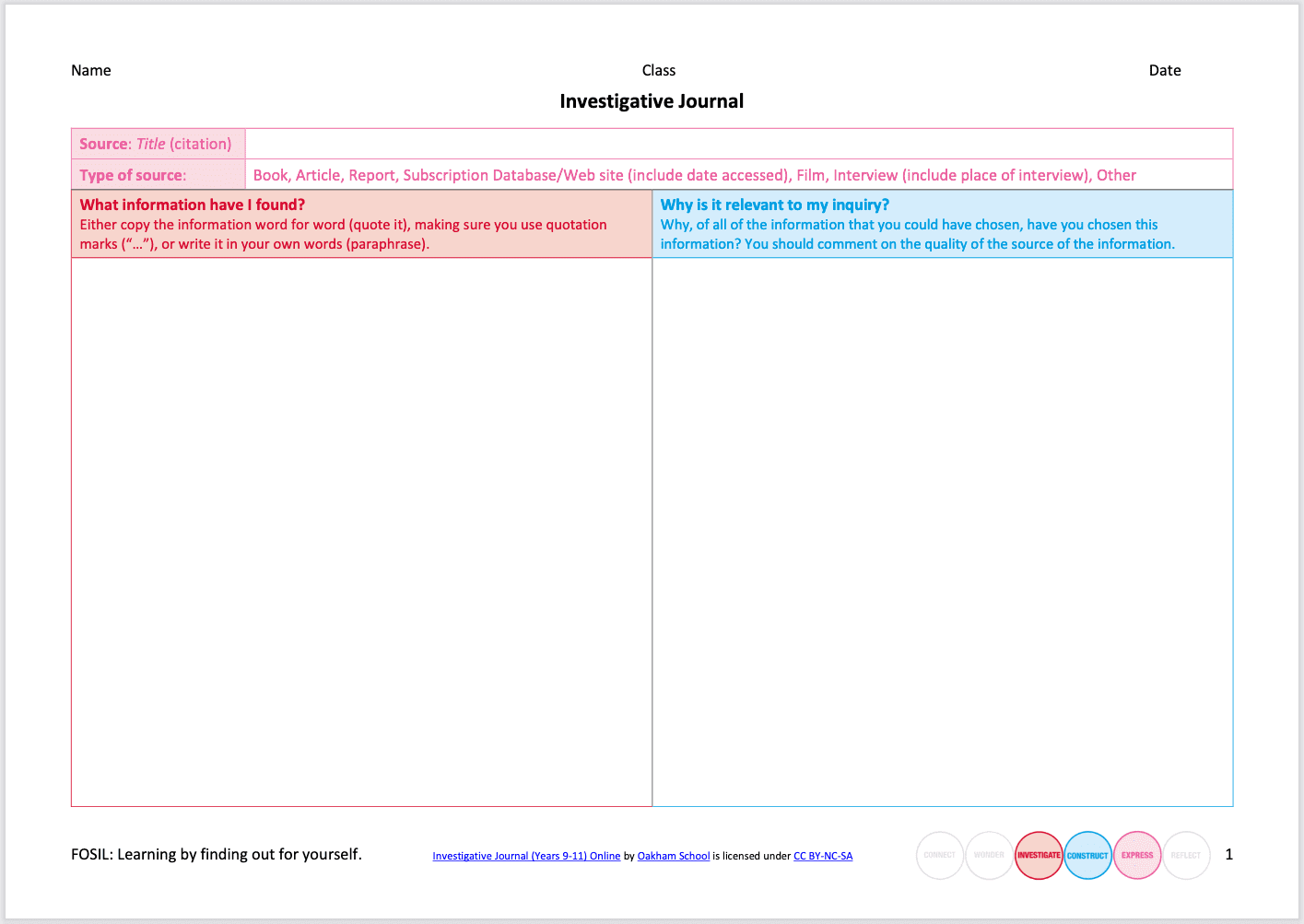

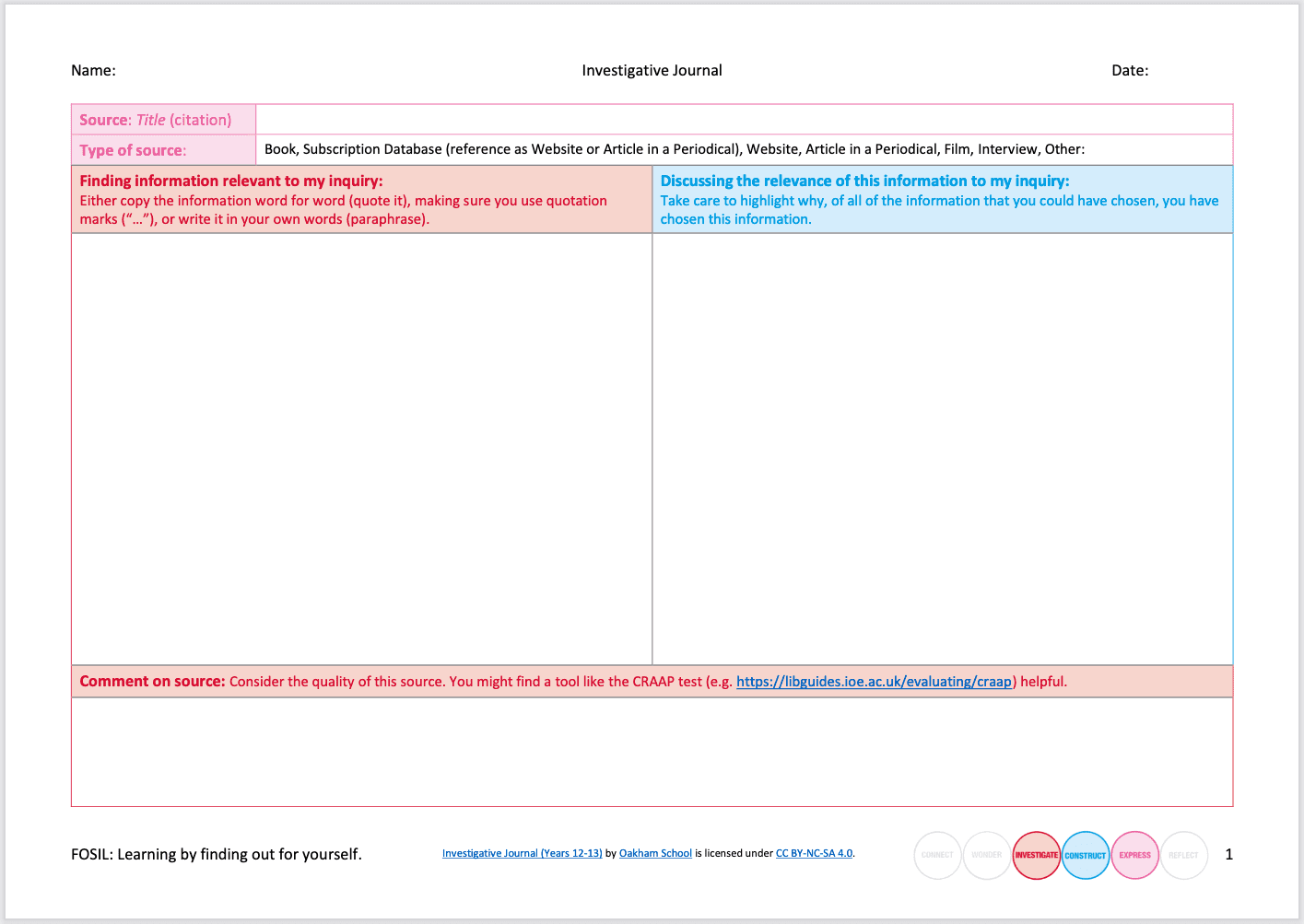

I’ll end with the example of how the graphic organiser that we designed to support the use of this skill [and others], which is then also evidence of the use of this skill, develops from Years 6-8, through Years 9-11, to Years 12-13. For examples of student work that this leads to, please see the Year 9 FOSIL Inquiry Skills Project and the and Year 9 Individual Project.

Figure 5: Investigative Journal for Years 6-8 (Grades 5-7)

Figure 6: Investigative Journal for Years 9-11 (Grades 8-10)

Figure 7: Investigative Journal for Years 12-13 (Grades 11-12)

8th February 2021 at 10:36 pm #35871

8th February 2021 at 10:36 pm #35871I’ve just finished mapping the ATL skills against the standards and indicators from the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (the root of FOSIL), and have shared this on the attached spreadsheet. Darryl is in the process of pulling all this into the mind mapping software we use and will share the more visual version (and the insights it gives) at some point in the next few days. The indicators are effectively categories that describe a line of skill development, while those lines of skill development within each indicator describe how the students’ competence should develop as they move up the school. For example, from Darryl’s example above on citing and referencing, the indicator is Express: Academic integrity (from Anchor Standard 1.1: Information-fluent learners use an inquiry process to connect to prior experience and background knowledge, wonder and ask questions, investigate, construct new understanding, express learning, and reflect on the process and product of learning, which is the part of the Information Fluency Continuum from which all of FOSIL is drawn). In this indicator, the expression of the skill in the classroom develops from:

- Recognizes the difference between own drawing or creation and someone else’s drawing or creation

in Reception (Pre-K) all the way up to the triple skill set of

- Cites all sources used according to standard style formats

- Embeds citations to specific information, visuals, or sound when appropriate

- Ensures that all completed products are plagiarism–free and all visuals and sound are used within copyright provisions

in Year 13 (Grade 12).

I think looking at the ATLs against the indicators like this is much more powerful than looking at individual skills in isolation because there is a sense of progression within each indicator (have a look at the Continuum section of the ESIFC website to see the skill progression. This is also in the FOSIL Skills framework, but we were working with the previous version of the ESIFC when we set that up, so the indicators were not divided into the helpful subsections). The progression attempts to answer the questions “Where had this student come from before they started the MYP, and where will they be going afterwards?”. As a subject teacher it was always very important to me to understand this progression. Like many Science teachers, I was always less comfortable teaching my non-specialist subjects in Junior Science. Not because I couldn’t do Biology or Chemistry at that level, but because I wasn’t also teaching them beyond it, so didn’t have an insight into where that subject was going and what foundations I needed to lay for work higher up the school in the same way that I did for Physics.

You wouldn’t dream of setting out a subject-based syllabus along the lines of e.g. (for Physics) “Develop your understanding of Forces over three/five years, from Novice to Expert level”. You would give some thought to what that might look like in practice, and what students would need to learn at each stage. I think this is equally important with skills. It isn’t about having a discrete skill and deciding whether the student has mastered it yet or not, it is about looking at how to progress that skill at a developmentally appropriate rate. I don’t think any of us truly believe that at the end of even a 5 year MYP a student will be an ‘Expert’ in all the inquiry skills they will ever need, so what does expert really mean in this context?

It is, of course, easy to criticize an existing framework and I am aware that a lot of work must have gone into setting up the ATLs, but there are many reasons why I think the ESIFC, and by extension the FOSIL skills framework, is more helpful to teachers than the ATL skill list. This is why we have made the effort to map across the two. It is also worth reiterating (as Darryl said above) that, as far as the IB are concerned:

Schools can use this list [of ATL skills] to build their own frameworks for developing students who are empowered as self-directed learners, and teachers in all subject groups can draw from these skills to identify approaches to learning that students will develop in MYP units.

MYP: From principles into practice (p. 64), emphasis added

As long as all the ATL categories and clusters (not the individual skills) are covered in a balanced way over the three/five years, IB schools do NOT have to use the specific 140 ATL skill list that the IB provide in an appendix to From principles into practice*. Our mapping shows that (with a very small handful of exceptions that I will explain in the next post) the full ESIFC (of which FOSIL is a significant part) covers all the individual ATL skills, and certainly all the categories and clusters. In terms of embedding skills progression in a meaningful way into the curriculum, it might actually make more sense for an individual school to use FOSIL (supported by the ESIFC) instead of that 140 ATL skill list. But even without taking that step, using them in tandem would still be a huge step forward.

[*Note, this is not just my opinion. Diane McKenzie, a very experienced teacher-librarian, library consultant, teacher trainer and IB workshop leader wrote this fascinating article about not getting too hung up on the ATL list in the FPiP appendix back in 2016.]

Attachments:

11th February 2021 at 3:38 pm #36030Thank you, Jenny.

I will post at greater length tomorrow (including downloadable posters), but wanted to preview Draft 1 of the mind mapping of the FOSIL and ATL skills integration based on the mapping in your Excel spreadsheet above (see Figures 1 and 2 below).

In short, as expected, a well-designed FOSIL inquiry will develop ATL skills from all 10 of the ATL skill clusters, and the spread of ATL skills will be even greater if we take into account the broader emotional and social development that occurs during the inquiry process.

Figure 1: FOSIL / ESIFC Reflected in the IB MYP ATL Skills

Figure 2: IB MYP ATL Skills in the FOSIL / ESIFC Skill Sets

11th February 2021 at 4:47 pm #36059

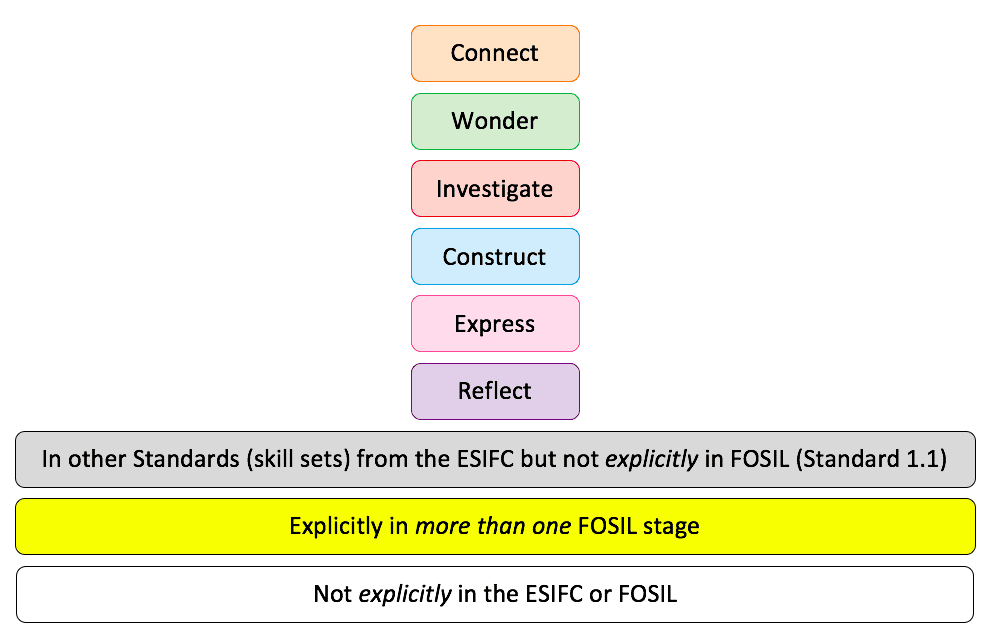

11th February 2021 at 4:47 pm #36059The ATLs and FOSIL are arranged quite differently. Darryl’s first diagram makes this very clear. Although you can’t read the words because the text is small (but this will be possible on the poster version he’ll publish tomorrow), actually this almost makes it easier to track patterns. I am in the process of putting together a selection of insights the whole process has given me, but in order to help you to interpret Darryl’s diagrams above we thought a key might be helpful (he will share this again on the posters tomorrow):

- Some of the ATL skills encompassed a vast range of skills in a single sentence, so we mapped several different rows of FOSIL skills to the same ATL skill.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.