Making Sense of Evidence in Education

Home › Forums › Effecting change and the roles of the subject teachers and teacher-librarians / librarians in inquiry › Making Sense of Evidence in Education

- This topic has 2 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 2 years, 3 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

7th May 2022 at 11:10 am #78945

This was originally posted to the Oakham School Teaching & Learning blog, which no longer appears to exist and so I preserve it here.

Making Sense of Evidence in Education

A blog post by Chris Foster

I’m grateful to Jenny Toerien and Julie Summers whose blog posts have encouraged me to commit my own thoughts to paper. I think Jenny’s post Locating Ourselves in the Epistemological Landscape raises important points about education as a contested field (Grenfell, 2012). I hope this post will help colleagues to find their way through the educational field more easily.

To make sense of educational research we need to acknowledge that most decisions we make on how we use evidence – whether systematic research, theoretical knowledge, school data or practical knowledge gathered by our experiences – are ideological decisions. This is because the notions of ‘education’ and ‘evidence’ are social constructs with meanings that are contested. We should therefore not be surprised if people understand these concepts in different ways (Wallace & Wray, 2011, p. 71).

In this post, I will argue that because of the contested nature of educational research, it is particularly important that we know where the data and methods we are using to make sense of evidence in schools sit in the field of education, and any underlying assumptions their use presumes. This is no small task for two reasons: not all teachers have experience of research in education, and the yawning chasm between practice in schools and research produced by university-based academics. To help with this, I propose two tools: a map of the field of education and an investigative journal for teachers to help them engage critically with sources. In a future post I will describe the different types of evidence we might draw upon as teachers and present another tool, a research proposal form to help budding practitioner researchers in schools focus their questions. These last two are adaptions of tools produced for postgraduate researchers that fit very well into Oakham’s FOSIL framework (Wallace & Wray, 2011; The FOSIL Group, 2019).

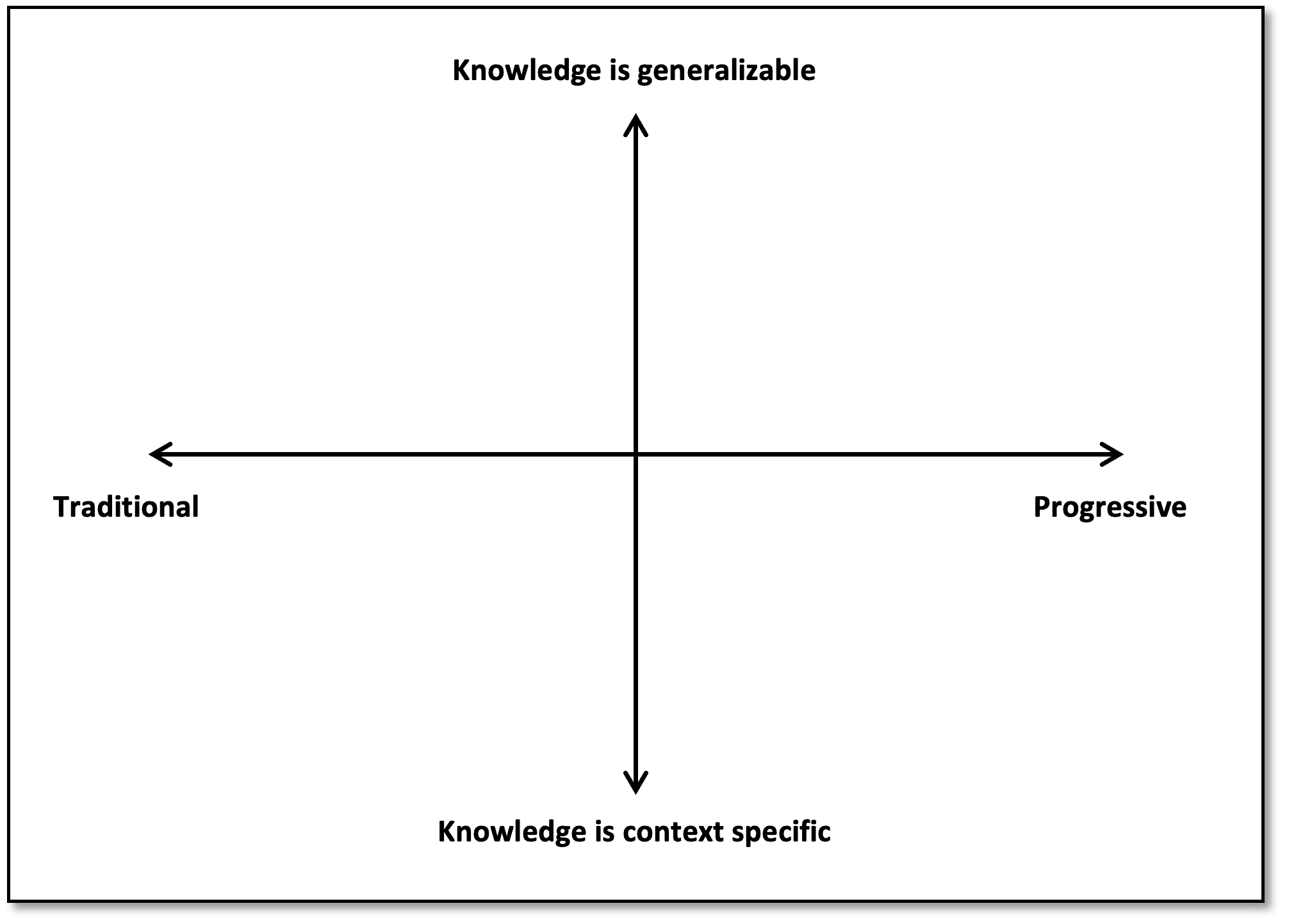

Mapping the field of education

The mental map I have produced is ‘simply a way of thinking about the social world so that different aspects can be considered and evaluated independently’ (Wallace & Wray, 2011, p. 70). The basic mental map is shown in Figure 1. Its purpose is to provide the critical reader with a simple map of the academic field of education. Like any map, it is an abstraction and a reduction. It’s not possible to include all the details and dimensions – it wouldn’t be a map if it could – but I think the two dimensions I have chosen (traditional/progressive and generalizable/specific knowledge claims) have the most explanatory power in the context of schools and school teaching. Both dimensions should be thought of as changing gradually from one extreme to the other.

The map’s x-axis illustrates my point about the foundations for many decisions in education. Where an individual’s approach falls on the traditional/ progressive continuum is an ideological decision. The y-axis plots how we think about knowledge in schools, and the features of knowledge that we think is of most use to us. Do we place more weight on widely generalizable knowledge collected from large trials or the fine detail of local case-studies? Again, this is an ideological position.

We can use this mental map to orient ourselves in the educational field. The strength and weakness of this tool is the way it reduces a complex field down to two dimensions, which can be an oversimplification. However, once we have acknowledged our own position in the field and can recognise that of others, we move beyond a situation where people from different ideological positions are talking past each other can approach differences as a start of a conversation. I have departmental colleagues who hold different pedagogical views to my own, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that one of us must be wrong. Our challenge is to see what we can learn from each other.

Figure 1: A mental map of the field of education

A similar approach can be taken with educational research too. We can use the type of research methods a researcher employs to gather data and how they think about curriculum content and skills to place a piece of research on our mental map. In this case, the y-axis indicates the degree of generalization of knowledge claims made by a piece of research. Knowledge that is very context-dependent is usually endogenic, created in a school for local use. At the other extreme, highly generalizable knowledge is often exogenic, produced by the academy and designed to be widely applicable.

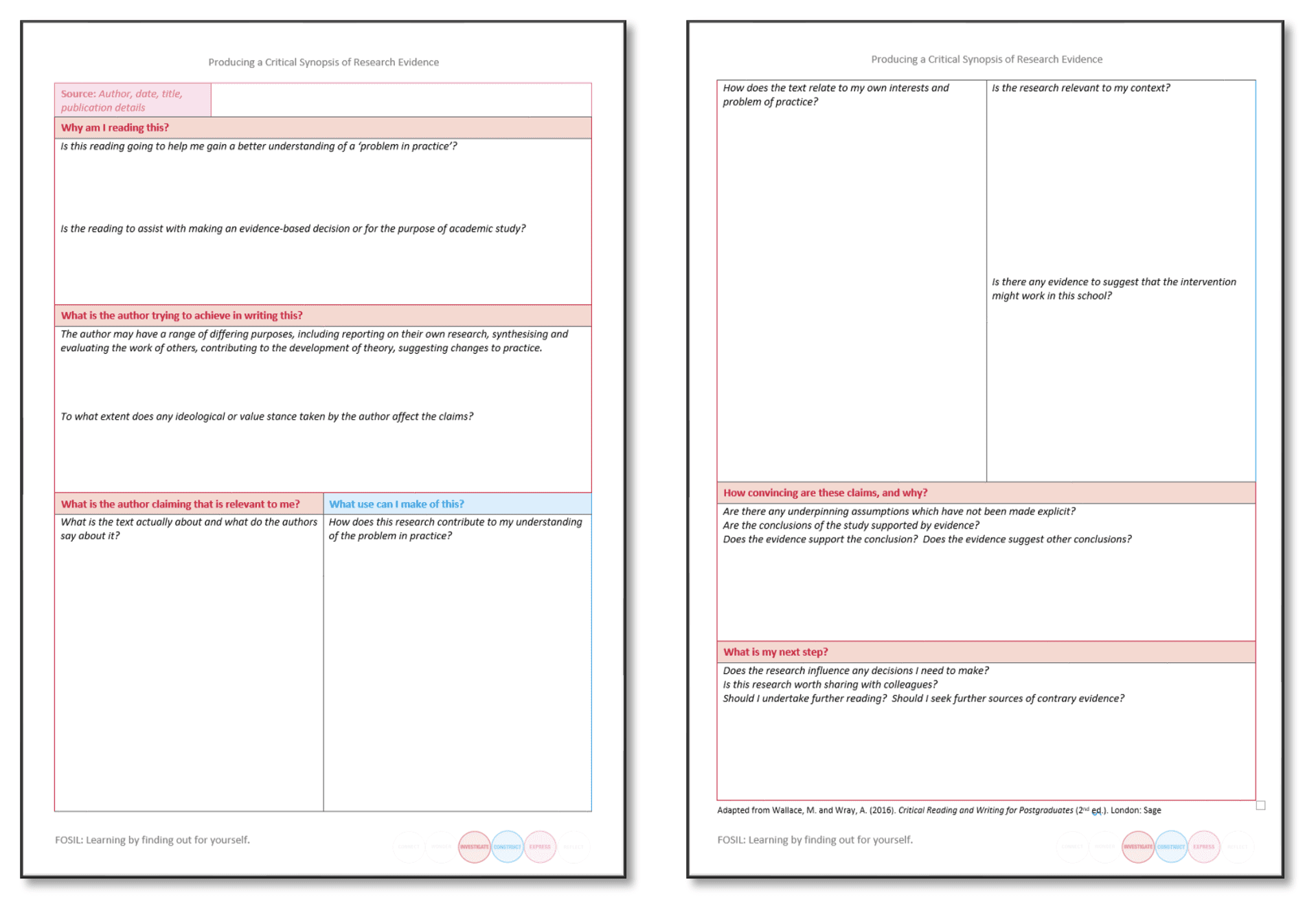

How can we read more critically? The Critical Synopsis of Research Evidence tool

Thinking about where the research might be placed on the map is a step towards recognising the ideological position of the author and underlying assumptions the work is based upon; this can help us to view research as a dialogue between author and reader. The Critical Synopsis of Research Evidence tool can help us with this task of making sense of our practice by interrogating evidence. The tool (which can be downloaded here) is shown in Figure 2. I have adapted the work of Wallace and Wray (2011, p. 238) and Jones (2018, p. 106) to produce the tool, and given it a FOSIL twist by using the structure and colours familiar to users of FOSIL materials. These place different aspects the task into the appropriate inquiry stage. The tool is designed to work in a similar way to the FOSIL Investigative Journal (The FOSIL Group, 2019).

Figure 2: The Critical Synopsis of Research Evidence Tool

To encourage the reader to think about the claims a piece of research makes and what this means to our practice in school, the tool asks the following questions of the evidence:

- Why am I reading this?

- Is this reading going to help me gain a better understanding of a ‘problem in practice’?

- Is the reading to assist with making an evidence-based decision or for the purpose of academic study?

- What is the author trying to achieve in writing this?

- To what extent does any ideological or value stance taken by the author affect the claims?

- What is the author claiming that is relevant to me?

- What is the text actually about and what do the authors say about it?

- How does the text relate to my own interests and problem of practice?

- What is the author claiming that is relevant to me?

- What use can I make of this?

- Is the research relevant to my context?

- Is there any evidence to suggest that the intervention might work in this school?

- How convincing are these claims, and why?

- Are there any underpinning assumptions which have not been made explicit?

- Are the conclusions of the study supported by evidence?

- Does the evidence support the conclusion? Does the evidence suggest other conclusions?

- What is my next step?

- Does the research influence any decisions I need to make?

- Is this research worth sharing with colleagues?

- Should I undertake further reading? Should I seek further sources of contrary evidence?

I think it is also important for us to realise that there are different types of evidence we might draw upon in schools. In a future post I will describe the different types of evidence we might draw upon as teachers and present another FOSIL-based tool in the form of a research proposal form to help budding practitioner researchers in schools focus their questions. This new FOSIL tool is an adaption of the ‘educational prescription’ used in the training of medical students in Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) (Straus, Richardson, Glasziou, & Haynes, 2005).

Bibliography

- Grenfell, M. (2012). Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jones, G. (2018). Evidence-Based School Leadership and Management. London: Sage.

- Straus, S., Richardson, W., Glasziou, P., & Haynes, R. (2005). Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. Third. Elsevier; Philadelphia, USA: 2005 (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

- The FOSIL Group. (2019). An introduction to FOSIL. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from The FOSIL Group: Advancing Inquiry Learning: https://fosil.org.uk/

- The FOSIL Group. (2019). Invesigative Journal. Retrieved January 30, 2020, from FOSIL Group: https://fosil.org.uk/resources/

- Wallace, M., & Wray, A. (2011). Critical Reading and Writing for Postgraduates (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

2nd October 2023 at 7:41 pm #81407I read this post with interest today after reading a book I found in our Staff Library called Children as Decision Makers in Education by Sue Cox, Caroline Dyer, et al. This led me to this Guidance for Teachers from 2007 https://www.participatorymethods.org/sites/participatorymethods.org/files/Children%20Decide%20UEA%20%202007.pdf. Entitled ‘Children Decide: Power, Participation and Purpose in the Primary Classroom’, the guidance was written after six schools – teachers and the children in their classroom – took part in action research to understand how children are involved in decision making in the classroom and the effects that their work had on the classroom, curriculum and on teaching and learning.

I am thinking a lot about inquiry learning in the context of High Performance Learning (I will start a new thread about this!) and about how to effect the mindset shift needed to embed inquiry in the classroom and the Teacher Guidance linked above is interesting in a couple of different ways. Firstly, that in looking at children’s role in decision making in the classroom, changes were made to the processes of the classroom.

“An emerging conception of the project was that decision making should not be seen as an end in itself, but as a ‘principle of procedure’ for working with children across the whole curriculum. We felt that the project could affect the whole school ethos in this way and had the potential for remodelling and transforming the curriculum. A focus on decision making foregrounded learning ‘how. Similarly, the way in which the project encouraged ‘enquiring minds’ signalled a shift in the curriculum towards processes of learning, rather than emphasising content. There were some changes in the classroom culture as a result of the project. For example, where there was a focus on behaviour, children took more responsibility for themselves, because they were making more of the decisions. Such changes were indicative of the way that children were being empowered to make decisions about their learning.”

This perhaps could be a vehicle for driving a mindset shift?

However. One of the essays in the book is entitled ‘Children as researchers: experiences in a Bexley primary school’ and details their work facilitating children to research their own topics (Why can’t we ride horses to school/why do people steal) and it is interesting to read their report of their work. “‘Children as researchers’ goes beyond an inquiry approach to learning – it enables children to contribute to discussions and understandings of their world in a more equal way as they can back their views with the weight real research offers”. Which shows something of a misapprehension of what inquiry learning is and how it differs – or not – from (action) research and I think points to the problem! I think there is a certain inbuilt irony to the process of creating an action research project to create more inquiry in the classroom – or at least to create the environment which is conducive to facilitating the ‘knowledge to understanding’ journey of both the students and the teacher.

30th October 2023 at 11:02 am #81682Thanks for this, Mary-Rose.

Some quick thoughts.

Your observation underscores Neil Postman’s point – made with Charles Weingartner more than 50 years ago! – that “of all the ‘survival strategies’ education has to offer, none is more potent or in greater need of explication than the ‘inquiry environment'” (1971, p. 36, emphasis added). This remains the case, and realizing the educational promise of inquiry requires some understanding of the debilitating tendencies that rob inquiry of its potency, four of which we addressed most recently in our AASL presentation – Leading an Inquiry-Based School: Discovering the Promise – which are:

- Inquiry as a dynamic process and skills is divorced from learning important content.

- Inquiry is reduced to a mechanical process with no spirit of wonder and puzzlement.

- Without both a spirit of wonder and puzzlement and a dynamic process, inquiry is reduced to a thoughtless fact-finding activity.

- Increasing emphasis on the “engineering of learning” based on ‘hard evidence’ from the field of cognitive science endangers the possibility of inquiry.

What we have yet to address is the extent to which an individual school is, or isn’t, what John MacBeath (1993) termed an enabling environment, and discussed so perceptively.

In the context of inquiry, the work of the Developing Inquiring Communities in Education Project (DICEP) is extraordinary. DICEP started in 1991 as a collaboration between teachers in public schools (Grades 1-8) in metro Toronto and surrounding areas and university teacher educators at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) of the University of Toronto. Over 10 years, the Project saw a shift in focus from “a study of ‘Learning through Talk’ in elementary science classrooms [to] creating opportunities for inquiry-based learning and teaching at all levels and in all areas of the curriculum” (p. 2).*

Gordon Wells, who led the collaboration, concludes with the following observations:

- “In general terms…the force that drives the enacted curriculum must be a pervasive spirit of inquiry, and the dominant purpose of all activities must be an increase in understanding.” (p.7)

- “However…there is no straightforward, universal method of achieving these goals .” (p.7)

- “Each classroom is thus unique. And so, if teachers are to create communities that work collaboratively toward shared goals while valuing diversity of opinion…and, at the same time, are to foster individual initiative and creativity, they also must approach the task in a spirit of inquiry….In fact, teacher and students together must become a community of inquiry with respect to all aspects of the life of the classroom and all areas of the curriculum.” (p.7)

- “First, if classrooms were to become places where students were actively and enthusiastically attempting to construct answers to questions that were of real interest to them – rather than simply going through the routines of ‘doing school’ – more would be needed than the introduction of prepackaged inquiry activities, taken from teachers’ manuals or downloaded from the Internet.” (p.8)

- “Second…a great deal hinged on being able to change the habitual patterns of interaction in the classroom, with their built-in assumptions that it was teachers, not students, who were entitled to ask questions and that such questions should be the ones to which there were correct answers, already known by the teacher….really interesting questions rarely had simple answers.” (pp.8-9)

- “Not only do schools, as institutions, have established patterns of organization…that make it difficult to depart from traditional practices, but both teachers and students have been enculturated into roles and routines that are often hard to break.” (p.9)

- “Every classroom is unique in respect to the persons it brings together, the resources available to them, and the constraints under which they operate. This means that any theory of pedagogy or curriculum necessarily has to be adapted and modified according to local conditions. There is, however, a much more fundamental reason for the failure of top-down reform, namely, that the relationship between academic theory and the practice of teaching is much less direct than the implementation model implies.” (p.16)

- “In the long term…for change to become institutionalized it must be appropriated by those who are involved on a continuing basis, and enacted in the moment-by-moment decisions that make up daily classroom practice.” (p.15)

As for the misapprehension of inquiry in relation to research, we explored this in an INSET session at Blanchelande – Blanchelande 2023 | No Mo FOFO: Developing Inquiry Through Research Homework – from which I quote:

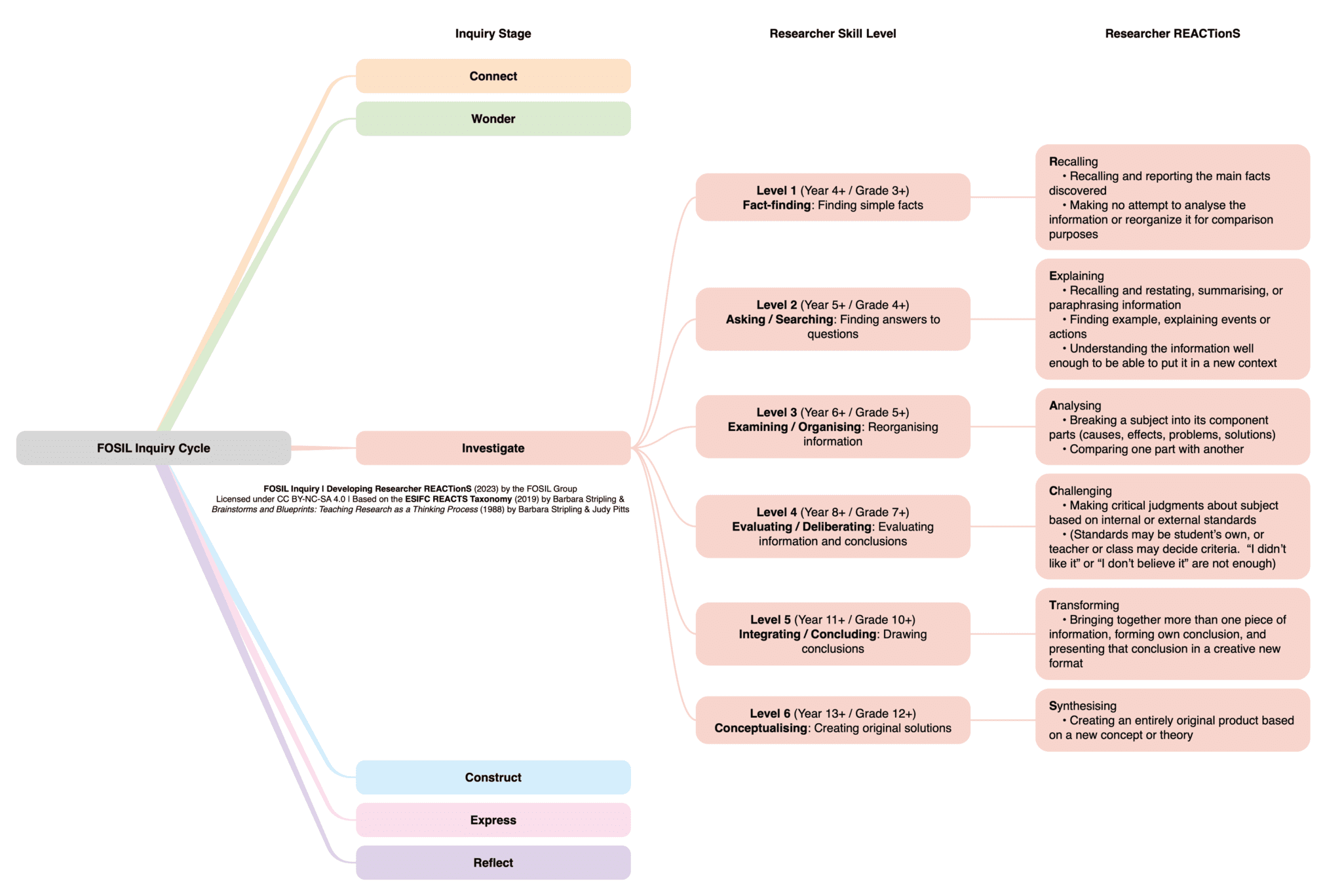

Research is integral to inquiry – mainly in, but not limited to, the Investigate stage of the inquiry process – and aims at “generating evidence for [answering] the chosen/ given question through empirical investigations of various kinds and/ or from consulting relevant [and reliable] sources” (Wells, 2001, p. 191). By definition, then, all research is thoughtful, but only thoughtful research tasks actually develop researchers. And in turn, inquirers.

This misapprehension is what happens when inquiry is divorced from learning important content.

*The work of DICEPS was foundational for the Galileo Educational Network (GEN), which served as the professional learning arm of the School of Education at the University of Calgary from 1999-2022, whose defintion of inquiry ours is enlarged from:

Inquiry is a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community.

References

- Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. (1971). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- MacBeath, J. (1993). Learning for Your Self: Supported Study in Strathclyde Schools. Strathclyde : Strathclyde Regional Council.

- Wells, G. (2001). The Development of a Community of Inquirers. In G. Wells (Ed.), Action, Talk, & Text: Learning and Teaching Through Inquiry (pp. 1-23). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Why am I reading this?

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.