Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College

Home › Forums › Inquiry and resource design › Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College

- This topic has 18 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 7 months, 3 weeks ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

14th June 2024 at 9:07 am #83623

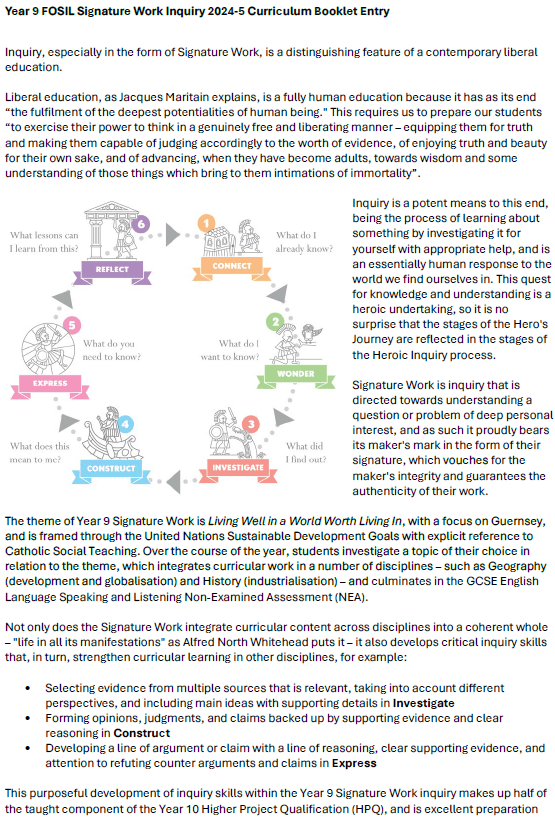

A quick update.

The Year 9 Signature Work Inquiry leads to the GCSE English Language speaking and listening Non-Examined Assessment. Students are currently presenting their 5-minute speech, which is followed by a 5-minute Q&A, and I am very pleased with the quality of their work.

I am also delighted that FOSIL Signature Work Inquiry will be a timetabled subject for Year 9 next year, with an allocation of 1 lesson and 1 homework a week, which I will teach. This will allow me to develop this inquiry even more purposefully.

Meaningful curricular links with English and Geography (sustainable development) remain, and I am developing a meaningful curricular link with Theology in terms of Catholic Social Teaching.

I have produced a brief overview of the inquiry below:

I am now working on a subject overview and description for the Curriculum Information for Lower Seniors booklet, which I will share when done.

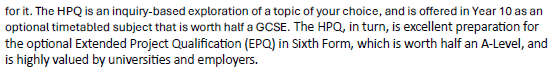

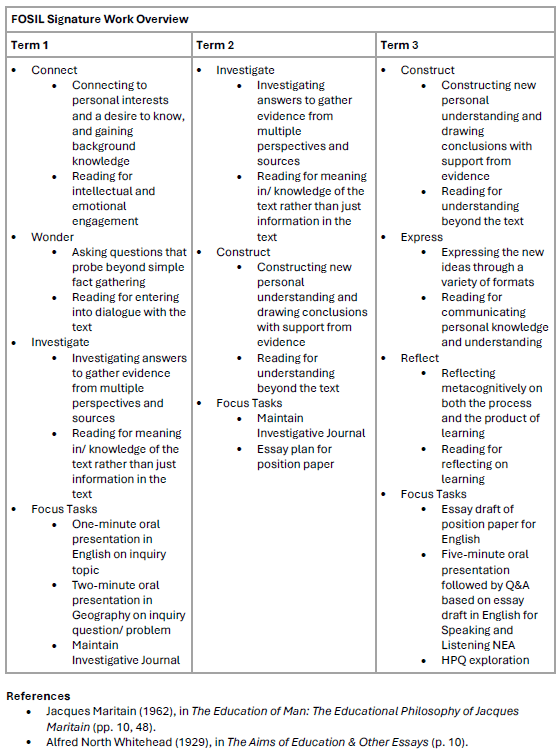

10th December 2024 at 3:00 pm #85123I can’t believe the first term is about to end, with so much that I have yet to reflect on.

However, I can quickly share the subject overview and description for the Curriculum Information for Lower Seniors booklet (see below or download as a PDF):

11th March 2025 at 3:05 pm #85777

11th March 2025 at 3:05 pm #85777In Defence of the Essay

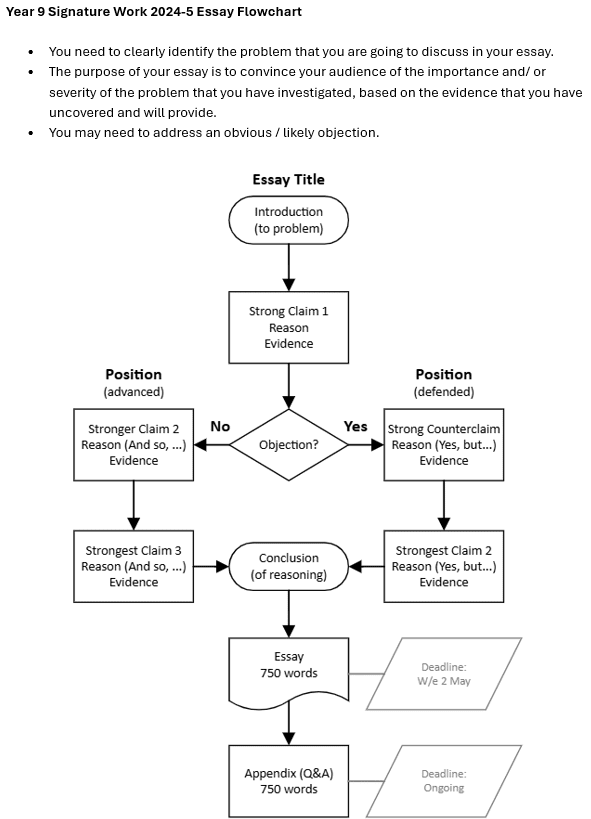

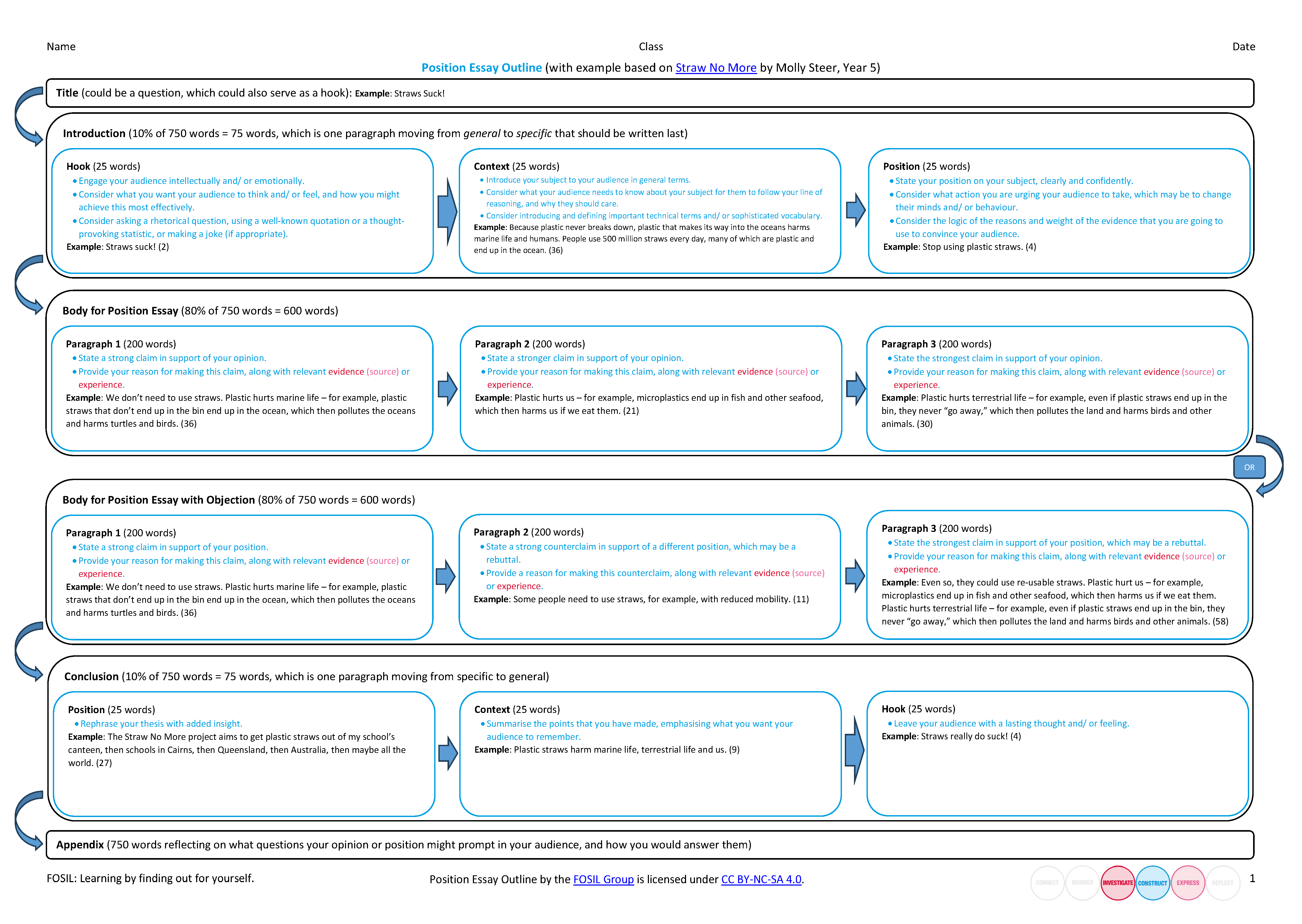

We have reached the point in the Year 9 Signature Work inquiry where we shift our focus from thoughtful reading to thoughtful writing, which will take the form of a 750-word essay in which students will (a) clearly identify and define the problem that they intend to discuss, and (b) attempt to convince their audience of the importance and/ or severity of the problem based on evidence that they uncovered during their investigation and will present in their essay.

Why, one might ask, as some do, teach students to write an essay if AI can write a better essay? Now while there may be more to this question than at first appears, it is, as asked, a question that demands an answer.

The simple answer is that we are not, in fact, teaching students how to write an essay, but to think, with the essay in this case being a tool to think with, and a particularly powerful one at that.

This distinction may seem pedantic, but is, in fact, profound, especially as AI intrudes its way into every aspect of our lives.

As Christopher Newfield (2025) writes:

My root worry about AI has always been that while it was making machine learning better, it was also making human learning worse. I am not alone in this. Teachers, who are responsible for helping students think, were increasingly furious about what AI was doing to the student brain.

A week before ChatGPT was released, Jane Rosenzweig, director of Harvard College’s Writing Center, made what should be an obvious point: “Writing—in the classroom, in your journal, in a memo at work—is a way of bringing order to our thinking or of breaking apart that order as we challenge our ideas. If a machine is doing the writing, then we are not doing the thinking.”

…

I draw several conclusions here.

…

Second, the high-value economic benefits of AI require fully empowered human use of AI as tools. Benefits will depend on society devoting much more effort than it now does to the expansion of human capabilities, rather than seeing technology as rescuing society from the self-inflicted enshittification of its human systems. The rigourous teaching of writing and thinking is more essential than ever.

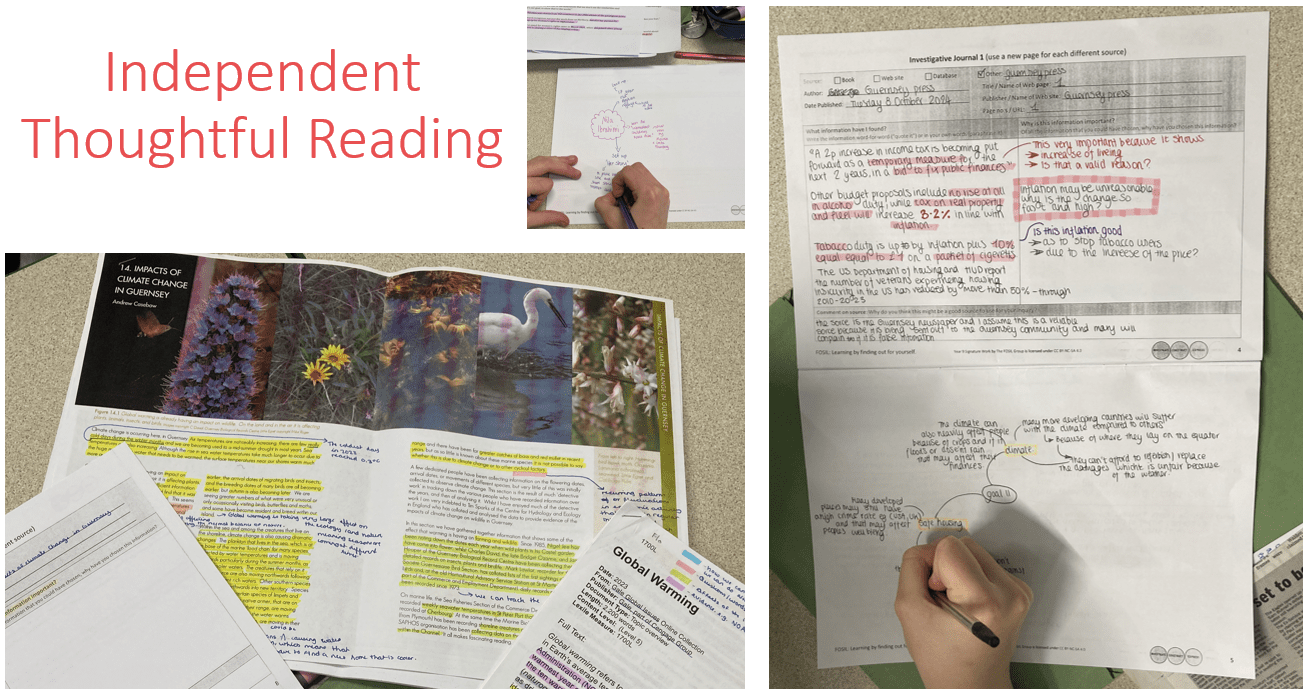

Students have now spent a term investigating a SDG-related problem that they have identified and defined, which is a distinguishing feature of Signature Work inquiry. I have been deeply impressed by how purposefully many students in this cohort have used their Investigative Journals as tools to think with.

The next step, however, is daunting, even for university-level students, which is why there is real value in helping students with this in school. As Newfield (cited above) explains:

I learned during my decades of teaching university-level writing that students can mostly find a general topic that interests them. But they struggle with the next question: what do you want to say about your topic? What’s your thesis, your claim, about it? This stage turns out to be very hard, and the simple reason is that it’s where independent thinking has to happen. It’s where the student diverges, however slightly, from what has already been said. If a GPT product is available, the student—or anyone, myself included—will be tempted to use it to skip this thinking stage.

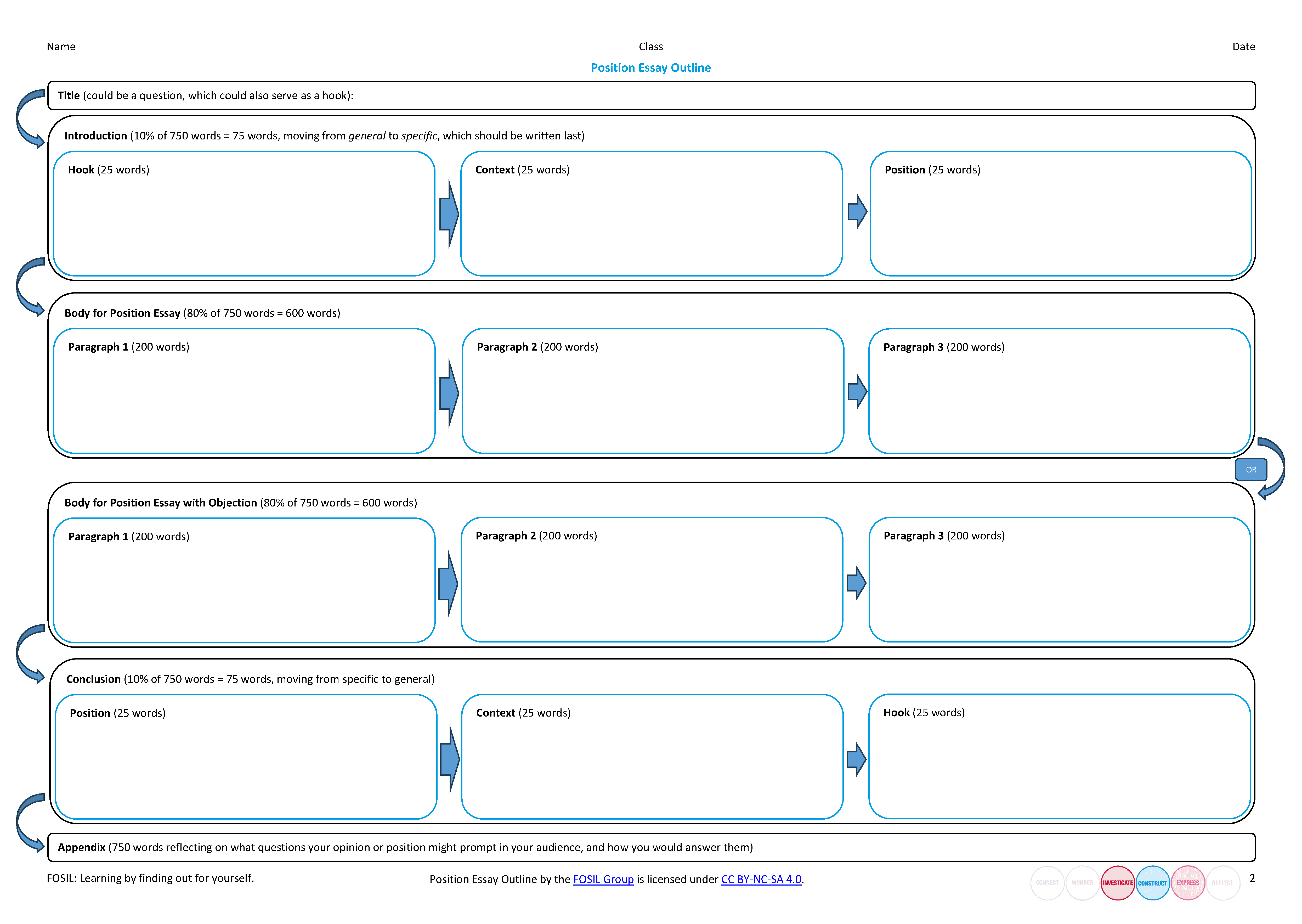

To help students with this last year, I developed the Opinion Essay and Position Essay flowchart and graphic organiser (see post #83043 above). This year I have simplified the flowchart and graphic organiser slightly (see below), and also added an example to the graphic organiser based on the Straw No More presentation by Molly Steer at TEDxJCUCairns (2017), which we looked at in class.

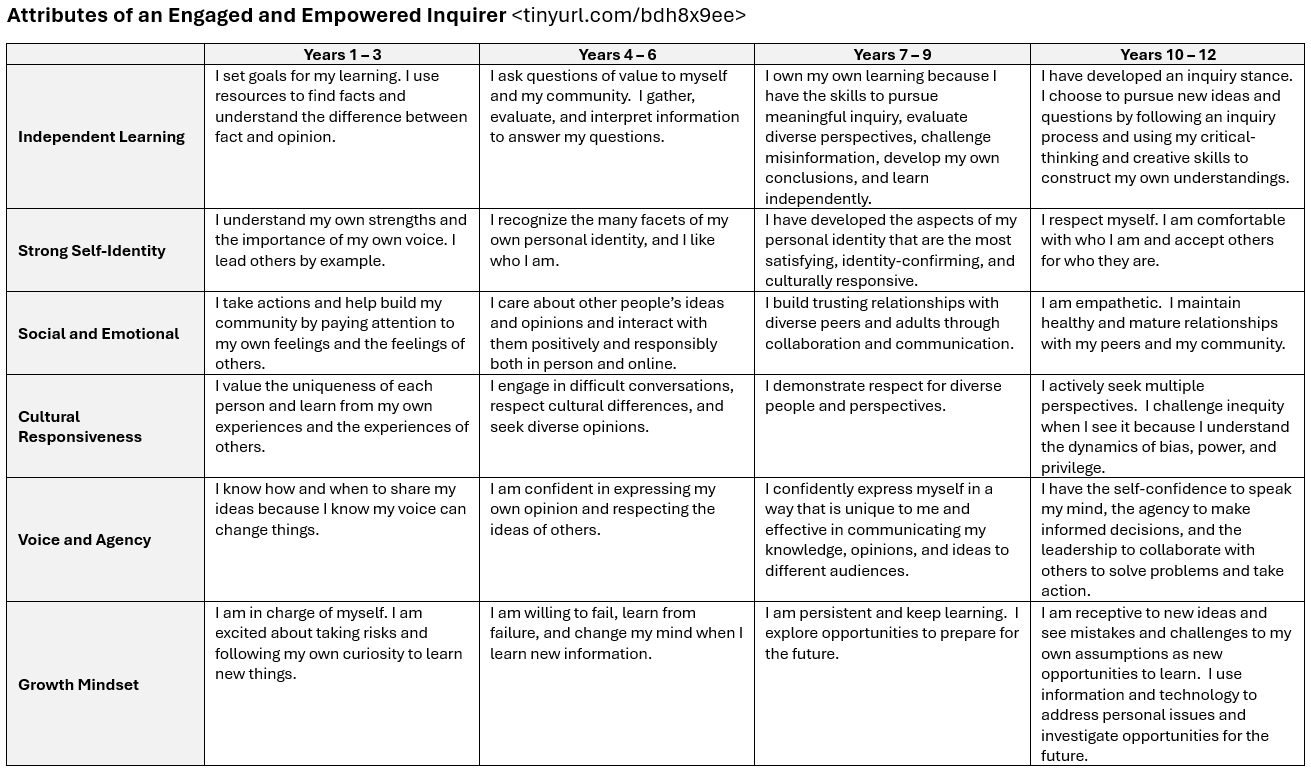

This is the critical moment, as Newfield highlights above, when students become more fully themselves, or less, as they face twofold temptation of letting the machine [and its programmers] think for them and speak for them–as Janet Salmons (2025, emphasis added) warns, “the implicit message [of AI offering to (re)write for you] is less than subtle: use the words we tell you to use, in the style we tell you to use, to say what we tell you to say, in the voice we tell you to use,” which is bringing about a “‘flattening’ of contemporary writing.” This is when I must trust that I have sufficiently “encouraged [my] students to engage in the process of acquiring knowledge, which is a very difficult process, [without which] all you get is memorisation and reproduction in tests” (Young, 2022), or in this case, copy & paste. This encouragement to engage–to Connect–takes time and energy, to be sure, but time and energy well spent on enabling my students to develop as engaged and empowered inquirers, increasingly willing and able to learn for themselves.

My confidence is high.

References

- Newfield, C. (2025, March 4). The Fight About AI. Retrieved from Independent Social Science Foundation: https://isrf.org/blog/the-fight-about-ai

- Salmons, J. (2025, January 28). Finding Your Voice in a Ventriloquist’s World – AI and Writing. Retrieved from The Scholarly Kitchen: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2025/01/28/guest-post-finding-your-voice-in-a-ventriloquists-world-ai-and-writing/

- Young, M. (2022, September 21). What we’ve got wrong about knowledge & curriculum. (G. Duoblys, Interviewer) Tes Magazine.

24th June 2025 at 1:08 pm #86956On Thursday, 19 June, we held our third annual Year 9 Signature Work Inquiry Celebration.

As I explained to parents, the Signature Work poster is similar to an article’s Abstract, in that it both summarises a larger body of work and reflects a learning journey that is itself embodied and situated.

This year I gave parents an overview of what this learning journey entailed: deeply thoughtful reading into a personally-chosen topic related to the theme; a 1-minute speech in English; a 2-minute speech in Geography; a 750-word essay plan overview; an essay plan; a handwritten draft essay; a typed re-draft; a typed re-draft in response to feedback, and; cue cards for the 5-minute speech in English.

As is customary, one student was chosen to represent Year 9 with their speech, and this year we could not be prouder of Flo.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.