FOSIL and the IB Diploma Programme Extended Essay (EE)

Home › Forums › Inquiry and resource design › FOSIL and the IB Diploma Programme Extended Essay (EE)

Tagged: Extended Essay, IB DP

- This topic has 21 replies, 7 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 2 months ago by

Jenny Toerien.

Jenny Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

9th March 2021 at 2:26 pm #37900

All of this reminds me that I soon need to turn my mind to our EPQ support, which will build on the EE support. Currently Chris Foster, our Head of Student Research supervises all of our EPQ students (for us it’s a smaller cohort than for the EE) and delivers an excellent support program for them, including some crossover from the EE support. Support for the EE and the EPQ has a lot in common, so for anyone interested it might also be worth exploring the FOSIL and the Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) topic too. We had an interesting discussion on supporting questionnaire design there last April which was very relevant for this year’s EE Investigation Days and led directly to Chris’ Nearpod ‘lesson’. I really liked Emily‘s suggestion of inviting someone in from the Marketing Department to talk to students, and that remains an option to explore for another year.

8th July 2021 at 1:54 pm #74732We would like to take a more FOSIL based approach to our EE. How do we go about introducing the concept of FOSIL to our students when they haven’t learnt in this way before. Do you talk about the FOSIL stages explicitly or do they become clear through you EE teaching. I would be really interested to know what topics are covered in each of your EE workshops, thank you, Liz

12th July 2021 at 6:30 am #75185Hi Liz

I am sure others will reply soon but I have found it easiest to introduce FOSIL separately. There are a couple of examples of presentations here

A brief introduction like this can then be reinforced as you start to teach the skills needed for EE.

12th July 2021 at 9:32 am #76575Thank you Elizabeth, that is really helpful, best wishes, Liz

18th September 2021 at 10:33 am #78415Hi Liz,

I’m so sorry I missed this one over the summer. We moved schools (and countries) to Blanchelande College on Guernsey which was quite an upheaval and took a lot of time and energy! It may be a bit late for you now, but in the next week or two I will post some more specific detail about what we did in each of our seminars in case that is helpful to you or to someone else in this situation. Broadley though you can see the content of each session on our LibGuide (check the Seminar 1 tab, for example. You can access the tab for each seminar either from the dropdown menu on the Seminars and Workshops tab at the top of that page, or by using the ‘Next’ button at the bottom of that page). You won’t be able to access the videos (which are on SharePoint) but you should be able to see the slides (Which are on Slide Share). I’m currently struggling with my internet connection and can’t see all the slides in that presentation on the LibGuide site for some reason, so will try to post some more stable links for you at some point as well. Be aware that at points where I mentioned the LibGuide in the presentation I usually then dropped out of PowerPoint and did a ‘live’ tour of whichever section of the guide I was discussing.

In answer to your question about FOSIL, the majority of our IB students were a new intake into Year 12 so I did not assume any prior knowledge of the cycle from lower down. The whole of Year 12 (IB and A-Level) had a short introduction to FOSIL during their induction days, but this was quite brief. While there wasn’t time to dwell too much on the cycle in isolation during the EE seminars, we always started with an overview and made it clear when we were stepping between stages (a simple transition slide in a presentation is often enough there). There was also a tab on the LibGuide giving more detail about the inquiry process for those who wanted to explore it. I think the most important feature of the guide and accompanying resources was the FOSIL colour coding as it helped to locate students in the cycle whether they were new to it or not. Whether or not you have an online space like a LibGuide for EE students, consistent use of colour coding and mention of the cycle in your presentations and resources can help locate them, and also makes FOSIL an integral part of the process rather than something that is just mentioned at the beginning and then forgotten. Students then learn to internalise the cycle by working through it rather than being told about it. Another important aspect is that FOSIL is both important for the students, but also for you in your planning and understanding of the inquiry process. The end goal is clearly for them to be able to internalise, understand and use the inquiry process rather than to ‘name the stages in the FOSIL cycle’.

I’m not sure if that rambling is helpful, but I am short on time this morning and wanted to make sure I had made a (very belated) start on answering your question. I will return to it as soon as I can….

21st September 2021 at 8:46 am #78417This week I ran an introduction to the inquiry process for year 12 at Ladies College in Guernsey for students starting their EPQ. I thought I would share my presentation with you in case anyone would find it useful.

Attachments:

2nd December 2024 at 8:25 pm #85069JCS are planning a revision of my 15 January 2021 article The role of the librarian in the IBDP and have kindly allowed me to preserve the original below. Bear in mind that this is a historical post. I am no longer in an IB school – my Level 3 focus now is the Extended Project Qualification and our support for that is very different. However, I think some of the lessons we learnt along the way are still valid and worth reflecting on.

“The role of the librarian in the IBDP

This guest post is by Jennifer Toerien. Jennifer is Curriculum Librarian for Upper School at Oakham School, where students have the option to study in International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IBDP). It was originally published on the Investigating Knowledge blog [no longer running] on 02 December 2020 and has been republished with permission.

If you are reading this you are probably in an International Baccalaureate (IB) school – which means you are very lucky because you almost certainly have a school librarian to support you. But what is the unique role that a librarian should have in your education, and how can you make the most of what your librarian is offering?

It’s not all about the books!

School libraries around the world are under threat (BBC, 2017; ABC news, 2017; Citylab, 2019). As school budgets are being squeezed, many regard a professional librarian (and often even a library) as a luxury they can’t afford rather than an educational necessity. The problem is largely one of definition, and of understanding (both among school leaders and librarians themselves) of what a school librarian does. And that is why the situation is often different in IB schools. The traditional definition of a librarian is “a person in charge of or assisting in a library” (1), where a library is “a building or room containing collections of books, periodicals, and sometimes films and recorded music for use or borrowing by the public or the members of an institution” (2).

In a world where so much information is freely available online, ebooks are on the rise and many print books are cheap to buy, some have even suggested that libraries should be replaced by a well-known online retail giant (Guardian, 2018). But regardless of the arguments about the importance of books in education (and I am convinced they are still very important), the real problem often lies in school librarians grounding their identity in books and reading, not in education. The central purpose of schools is education and that should be the central purpose of school librarians too. If “they aren’t buying what we’re selling” then maybe the problem is with us, not them!

Fortunately, the IB recognises this and has published a document entitled Ideal libraries (IBO, 2018) explaining (3) what you should be able to expect from your school library. It defines (school) libraries as “combinations of people, places, collections and services that aid and extend learning and teaching.” (p.2). Notice that books aren’t mentioned at all – not because they aren’t an important and valuable part of our job, but because they are a tool we use to achieve our purpose, not the reason we exist. This astonishing and inspiring document goes on to explain the key roles of the librarian, and I am going to use it to explain what you should be expecting from your school librarian, and why they are a fundamental part of your IB education.

So what does a school librarian do?

The IBO says in Ideal Libraries that:

Library/ians act as curators of information, caretakers of content and people, catalysts of people and services, and connectors to sources of information, multiliteracies, and reading. Librarians’ responsibilities are inspired by the learning environments they engage with, and in that capacity, they are co-creators of information with the school and the wider community. They challenge learners to seek appropriate information, to use sound methods of inquiry and research, and teach them to question the information they find and use. (p.5)

In short, your librarian is the person to know if you want to learn how to access and work with information to generate and/or answer an inquiry question. You might expect your librarian to have the skills to locate and access information on whatever obscure topic you may have chosen for your EE (or IA), but our role goes far beyond that. It’s our job to be able to teach you to understand how to journey from the vague stirrings of an interest in a topic all the way through to a carefully researched, tightly argued and appropriately sourced and referenced essay answering a thoughtfully worded inquiry question within the space of about nine months, reflecting as you go. In short, it is our job to turn you into an academic researcher (although we prefer the term inquirer).

Shaping the IB Extended Essay process

Your teachers and supervisors are subject specialists, but your librarian is the specialist in inquiry. “Inquiry is an approach to learning whereby students find and use a variety of sources of information and ideas to increase their understanding of a problem, topic or issue. It requires more of them than simply answering questions or getting a right answer.” (Kuhlthau, 2007, p. 2). More broadly, “inquiry is a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world, [and] as such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created” (Galileo Educational Network).

The Extended Essay may be your first major step into the type of inquiry where you have real freedom to choose your own topic, so it makes sense that it should be guided by someone who really understands the process. At Oakham School, our journey with inquiry began with an examination of the EE process and how it could be reshaped to support our students more effectively. In 2010 Darryl Toerien, the Head of Library, had been developing his understanding of inquiry through the work of Carol Kuhlthau and Barbara Stripling. He realised that the EE process that he had inherited when he joined the school in 2008 was largely driven by an administrative need to make sure that students met certain deadlines rather than by a deep understanding of the inquiry process and what it would take for them to get there.

[Image to add later: Oakham School’s first EE timetable (2001-3 cohort)]

Most glaringly, students were expected to select their research question within four weeks of their first introduction to the EE, but were then only given dedicated off-timetable time to work on the EE six months later, a week before their first draft was due. While they were expected to start gathering research materials much earlier, there was no real expectation of any substantial reading until EE “research week”, when they needed to do their reading and writing together in a fairly short concentrated space of time.

From his understanding of Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process, Darryl realised that the inquiry question only emerges from a deep understanding of the topic, achieved by using resources to investigate the topic and build understanding. You go into your investigation with an idea and a direction, and emerge with an understanding of an appropriate question to answer. He also realised that the most challenging, transformative and important work of the EE is not what is often called the “research” – finding resources and reading them – or even writing the essay. It is what comes in between those two – constructing a new (to you) understanding of your topic based on what you have read. This is what changes you and equips you to write an original, evidence-based essay, rather than a disjointed patchwork of other people’s thoughts. But this takes time and support.

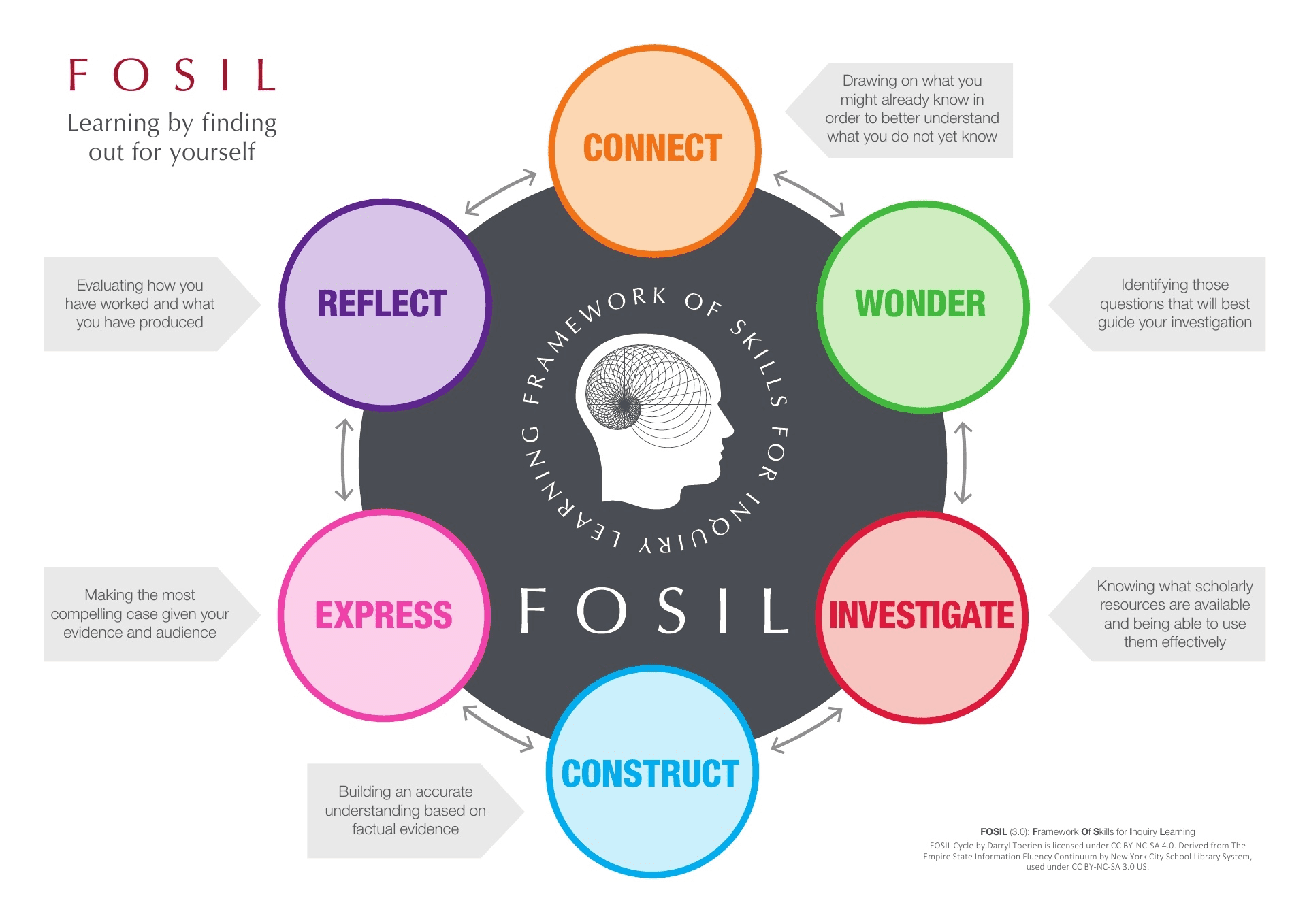

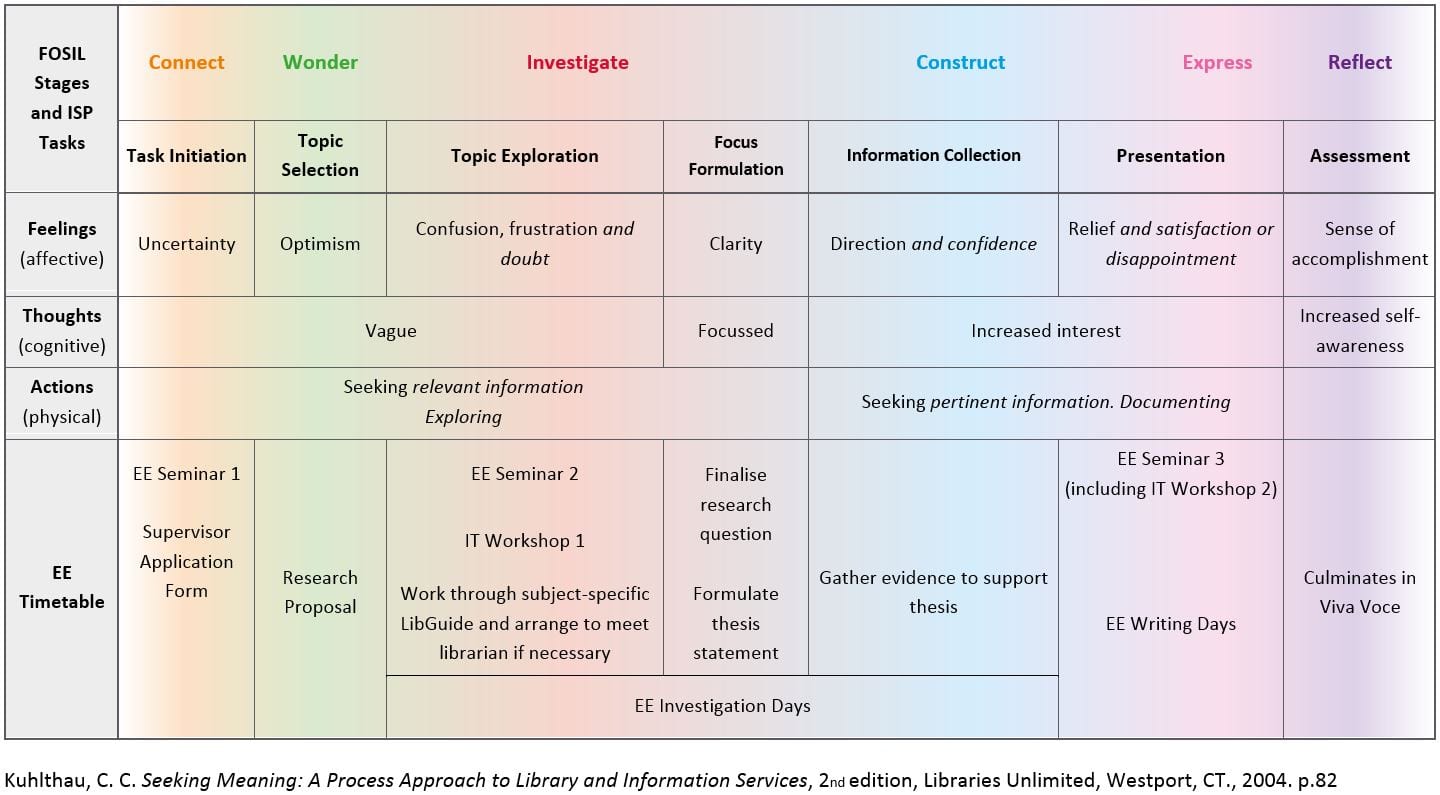

Our current timetable is based on a blend of Information Search Process and The FOSIL Cycle, developed by Darryl based on the Stripling Model of Inquiry within the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum.

The FOSIL cycle is a clear description of all the stages of inquiry, resting on a foundation of decades of research and it would require a blog post of its own to explain how the cycle works and the impact it has on teaching and learning – if you are interested visit the The FOSIL Group website for more information about the cycle, free downloadable resources and a community of educators sharing their ideas in our forum.

By understanding how the inquiry process works, we can guide our students more effectively through it. In this particular case we realised that students had almost no time for Connect and Wonder (the background research and exploration required to understand a topic well enough to ask good questions) and often skipped Construct (building understanding) altogether as they jumped from Investigate (finding out) to Express (writing).

Adding Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process, which described what students might be thinking, doing and feeling at each stage, into the timetable was the final piece of the puzzle.

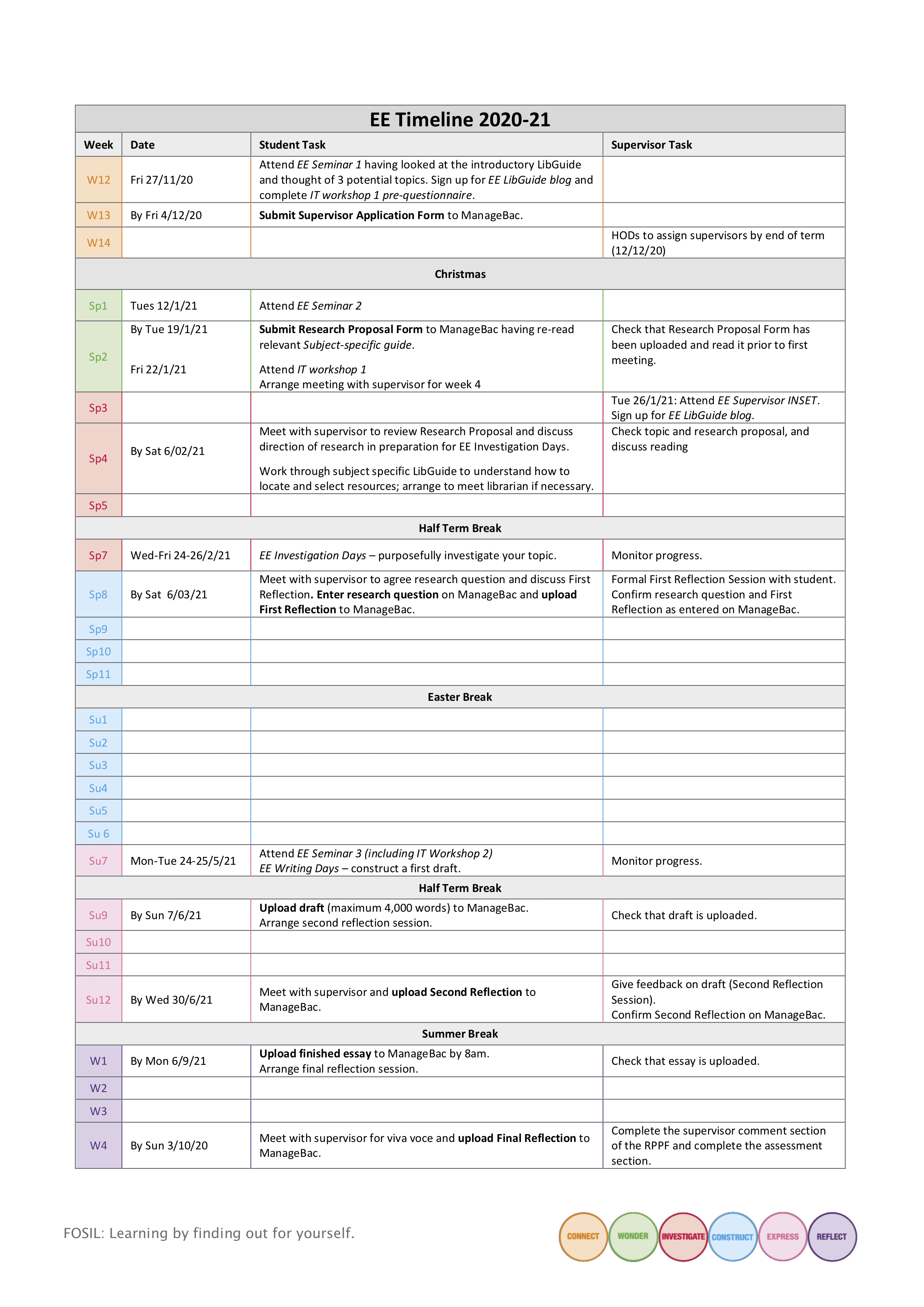

We began to understand how students might be feeling at different stages of the process and when the most appropriate times to offer support were. In terms of structured support (provided centrally to the whole cohort, as opposed to that provided by supervisors) we went from just one seminar at the start of the process to three, backed up by two dedicated IT workshops. We also split the Research Days into two chunks, giving students three Investigation Days off timetable to find resources and start working with them quite early in the process (February), with plenty of time to continue reading, follow up leads and acquire new resources, think through what they had read and discuss it with their supervisors in between that and the Writing Days (June). This Construct time is critical to helping students find their own voices. This is what the new timetable looks like in practice:

Hopefully you can see that this timetable is now informed by an understanding of the inquiry process and the student experience, rather than an administrative need for students to reach certain goals. The Library is also now integral to the EE process, not peripheral. This is the value of involving the Librarian in shaping the EE process.

Supporting the EE process

We now support the EE process through:

- Offering three compulsory targeted seminars at appropriate intervention points.

- Offering two compulsory targeted IT workshops at appropriate intervention points. As our provision has improved further down the school, we are finding more students arriving in the sixth form able to use the tools in Word to cite and reference and generate contents lists. This year we plan to offer parallel sessions for those who have never used these tools before and those who feel reasonably confident and just need a reminder.

- Supporting students in small groups and individually during the Investigation and Writing Days. It’s amazing how often students who thought they were pretty good at searching come out of these seminars surprised at how much they have learnt – if your library offers similar seminars it would be worth attending.

- Providing a web-based support resource (in our case a LibGuide) supporting students at every stage of the process. Our new EE LibGuide absolutely transformed our EE support last year, empowering students to access the support they need whenever they need it, moving through the process at their own pace. Having launched the resource in December 2019 with no idea of what was to come, the guide also enabled us to provide our strongest support ever, despite the coronavirus shutdown. We may continue to use some of the strategies we developed last year even after life returns to normal – for example using video tutorials for IT skills enables students to differentiate and self-pace and revisit in a way that live workshops do not, and allows them to choose PC or Mac based tutorials.

- Offering individual support as requested. We welcome individual requests by email or (before lockdown!) in person, and students often contact us for help finding resources on obscure topics and on citing different types of resources.

- Providing a broad and rich range of print and subscription resources, and purchasing new resources (or suggesting suitable alternatives) on request. Which leads us on to the third strand of the library service – and perhaps the one that springs to mind for most people when they think of the role of the library:

Resourcing the EE process

We have always emphasised using a wide variety of resources for in-depth research like the EE.

I. Books are perfect both for breadth – for reading around, becoming an expert in your topic and putting it into context. They are often (but not always) good academic sources, particularly when from well-known publishers, but you do still have to watch out for bias. Their biggest issue is the publishing time lag, which can mean it is harder to find a range of books about emerging issues, and the cost for niche academic texts.

II. Online journal articles often give very narrowly focussed depth (and can be very current) but have to be used carefully at this level because they can be too focused if you don’t have appropriate grounding in that area. Our most commonly used databases for the EE are EBSCO Advanced Placement source and JSTOR – and both have also proved invaluable last year for the range of ebooks they have during lockdown when the physical library was closed. We also saw increasing use of the Oxford Very Short Introductions ebooks, which offer the quality and depth of print books combined with the searchable convenience of online resources.

III. We have other subscription databases as well, and a third important category is targeted databases aimed directly at students at this level, which are increasingly starting to include video as well as print resources. We picked up the fantasticIdeas Roadshow’s IBDP Portal resource quite late in the process last year, when many of our students were already quite far into the investigation and were moving towards writing. As we approach the start of our EE process this year, I am confident that this innovative and exciting resource will really come into its own during the Connect stage of the FOSIL Cycle.

The short clips and compilations (each of which comes with an accompanying 1-page PDF providing lots of helpful information related to each video, including citing instructions) and the longer, in-depth conversations with world-leading researchers are ideal for students with a vague idea of the subject and perhaps topics they are interested in, but no clear direction. They are perfect for browsing and stimulating interest – and students who discover a line of inquiry that inspires them are assured of a one-hour detailed conversation with an expert in the field (with an accompanying PDF e-book) underpinning each clip or compilation to kick off their investigation!

Shaping you

As you can see from the above, although my role as a librarian does involve the traditional “librarian” activities of acquiring and curating resources, and helping my students to navigate them, it is actually so much bigger than that. I see my role directly as an educator. Perhaps more than anyone else in the school, it is the librarian’s job to nurture, enable and empower life-long learners because our subject is inquiry. I am not constrained by the need to teach my students to pass a Chemistry or Latin or Sports Science exam as well as teaching them how to think and learn independently – how to find, access, interrogate, assimilate, evaluate information and transform it into knowledge for themselves.

Not for me, not for the IB, not for the EE, not for their parents or their teachers. For themselves.

My students think I am supporting them through the EE, but my goal is so much larger. Done properly an EE can be a life changing experience that transforms a young person’s relationship with information and knowledge. It may well be the first time in your life when you realise that you have the power to turn yourself into an expert – when you realise that you know more about an academic topic than anyone around you, including your teachers, and that your thoughts and ideas matter.

I want to empower young people to question the narratives the world offers them, and to have the tools to seek authentic answers to those questions. I believe that the skills and attitudes that you learn through a relationship with your Library/ians during your school career will be vital for your success, not just at university but through the rest of your life.

As Ideal Libraries puts it:

“Libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin. The school may set the conditions for inquiry, encourage inquiry, and to some extent direct it, but learners must initiate inquiry for it to happen.”

You may think librarians spend all day hiding away in the library waiting patiently for someone to come in and ask for a book, but actually we’re hard at work (often late into the night) on changing the world, student by student. As the author and film-maker Michael Moore said of librarians back in 2002:

“They are subversive. You think they’re just sitting there at the desk, all quiet and everything. They’re like plotting the revolution, man. I wouldn’t mess with them.”

1) Oxford University Press. (2010) Librarian. In Oxford Dictionary of English, edited by Stevenson, Angus. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001/m_en_gb0468920

2) Oxford University Press. (2010) Library. In Oxford Dictionary of English, edited by Stevenson, Angus. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001/m_en_gb0468930

3) IBO (2018) Ideal libraries: a guide for schools. Cardiff: IBO. Retrieved 12 June, 2020, from: https://uaeschoollibrariansgroup.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/ideal-libraries-for-ib.pdf “

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.