Making a business case to allow for more FOSIL

Home › Forums › Effecting change and the roles of the subject teachers and teacher-librarians / librarians in inquiry › Making a business case to allow for more FOSIL

- This topic has 12 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 9 months ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

20th April 2021 at 3:49 pm #47257

I am writing to ask for your help. I’m a chartered librarian working alone in a large state, IB, secondary. I am employed to work 25hrs a week, term time only and have found that once I’ve managed the physical stock this leaves me with very little time to get my teeth into anything more substantial. I am very keen to persuade the school to use me more effectively and to really develop Inquiry skills across MYP and The IBDP.

In order to acheive this I am hoping to employ an apprentice to take on the role of a Library Assistant. If I am going to get the budget for this would I need to produce a business case. I am planning to use the IB school library guidelines and the IFLA documentation as the backbone of the case but just wondered if anyone else has already done something similar or has any experience or information which might help me.

Thank you in advance, Ruth

20th April 2021 at 3:54 pm #47260Hello, Ruth.

I have and am very happy to share.

How urgent is this?

Darryl

20th April 2021 at 4:59 pm #47276Thanks Darryl,

I’d like to complete my case in the next couple of weeks so that there is time for the Head to consider it as part of the budget process which begins next month.

Ruth

21st April 2021 at 5:24 am #47445No problem, Ruth.

I have a tight deadline for Friday, but will try to pull the main components together for you on Saturday.

Wishing you success in advance,

Darryl

21st April 2021 at 4:45 pm #47594Hello, Ruth.

I have uploaded the presentation that I prepared for Blanchelande College to FOSIL Presentations, which broadly outlines the case for a school library that is an enabler of FOSIL-based inquiry learning, and which is informed by the IFLA School Library Guidelines and the IB’s Ideal libraries: A guide for schools.

The PowerPoint presentation – Not for Lack of Vision – may be also be downloaded from here (some of the slides have explanatory notes).

I will add something more detailed on Saturday.

Darryl

21st April 2021 at 5:17 pm #47599Thank you so much for taking the time to do this now. I appreciate that Darryl

22nd April 2021 at 5:49 am #47741Always a pleasure, Ruth.

24th April 2021 at 12:10 pm #48301Simon Sinek (2009) makes the point that people do not buy into what we do (mission), but why we do what do (purpose).

Purpose, as I understand it, is the reason why we exist, and why it would matter if we didn’t.

The difference between why (purpose) and what (mission) is subtle, but profound, and I would bet that most cases for the school library would start with what the school library does.

This is the reason for starting my presentation with Harold Howe’s observation that what a school thinks about its library is a measure of how it feels about eduction – our focus is not what the school thinks about the library, but how the school feels about education. The fact that a school has committed itself to the IB MYP and DP – in which inquiry is a curriculum stance (Tilke, 2011) – strongly suggests that it feels a certain way about education, which predisposes it to thinking about its library in a certain way. Being clear, therefore, about how the school feels about education must be our focus and starting point.

While it will not be possible in the time available to develop this line of thought more fully, or even summarize it more helpfully, the following may be useful.

(All Guidelines are inspirational and aspirational – the more inspirational they are, the more aspirational they can be.)

—

It is not possible to discuss library staffing, especially in this country, without clarifying what we understand a school library to be within a broader educational context, which is why Harold Howe’s observation that “what a school thinks of its library is a measure of what it feels about education” is so insightful.

Our Benchmark for school libraries is the IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015).

Definition of a school library (p. 16) | A school’s physical and digital learning space where reading, inquiry, research, thinking, imagination, and creativity are central to students’ information-to-knowledge journey and to their personal, social, and cultural growth.

Distinguishing features of a school library (p. 17) | More than 50 years of international research, collectively, identifies the following distinguishing features:

- It has a qualified school librarian with formal education in school librarianship and classroom teaching that enables the professional expertise required for the complex roles of instruction, reading and literacy development, school library management, collaboration with teaching staff, and engagement with the educational community.

- In order to meet the teaching and learning needs of a school community, it is essential to have a well-trained and highly motivated staff, in sufficient numbers according to the size of the school and its unique needs. … The operational aspects of a school library are best handled by trained clerical and technical support staff in order to ensure that a school librarian has the time needed for the professional roles of instruction, management, collaboration, and leadership. (p. 25)

- See Australian School Library Association Recommended Minimum Information Services Staffing Levels (2020).

- It provides targeted high-quality diverse collections (print, multimedia, digital) that support the school’s formal and informal curriculum, including individual projects and personal development.

- It has an explicit policy and plan for ongoing growth and development.

Role of the school library (pp. 17-18) | A school library operates within a school as a teaching and learning centre that provides an active pedagogical program integrated into curriculum content, with emphasis on the following:

- Resource-based capabilities – abilities and dispositions related to seeking, accessing, and evaluating resources in a variety of formats, including people and cultural artefacts as sources.

- Thinking-based capabilities – abilities and dispositions that focus on substantive engagement with data and information through research and inquiry processes, the processes of higher order thinking, and critical analysis that lead to the creation of representations/products that demonstrate deep knowledge and deep understanding.

- Knowledge-based capabilities – research and inquiry abilities and dispositions that focus on the creation, construction, and shared use of the products of knowledge that demonstrate deep knowledge and understanding.

- Reading and literacy capabilities – abilities and dispositions related to the enjoyment of reading, reading for pleasure, reading for learning across multiple platforms, and the transformation, communication, and dissemination of text in its multiple forms and modes to enable the development of meaning and understanding.

- Personal and interpersonal capabilities – the abilities and dispositions related to social and cultural participation in resource-based inquiry and learning about oneself and others as researchers, information users, knowledge creators, and responsible citizens.

- Learning management capabilities – abilities and dispositions that enable students to prepare for, plan, and successfully undertake a curriculum-based inquiry unit.

Conditions for an effective school library program (p. 18) | Research has shown that the most critical condition for an effective school library pedagogical program (i.e., a planned comprehensive offering of teaching and learning activities) is a qualified school library professional.

Human resources for a school library (p. 25) | Because a school library facilitates teaching and learning, the pedagogical program of a school library needs to be under the direction of professional staff with the same level of education and preparation as classroom teachers. … In order to meet the teaching and learning needs of a school community, it is essential to have a well-trained and highly motivated staff, in sufficient numbers according to the size of the school and its unique needs. … The operational aspects of a school library are best handled by trained clerical and technical support staff in order to ensure that a school librarian has the time needed for the professional roles of instruction, management, collaboration, and leadership.

—

For comparison, the IB definition of a school library (Ideal libraries: A guide for schools, 2019, p. 2) | A combination of people, places, collections and services that aid and extend learning and teaching … The library and the librarian can be thought of as an interdependent system or a library/ian…that supports all learners’ and teachers’ progress towards becoming better inquirers, consumers and creators of information.

Libraries and inquiry (p. 9) | Libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin…and the librarian is responsible for energizing and maintaining the inquiry process. Ideally, the librarian is trained in many ways of creating conditions for inquiry within and beyond the classroom … Inquiry is more expansive than research, and facilitating it requires expertise beyond research methods (Callison, 2015 and Levitov, 2016).

Conclusion (p. 12) | The IB strongly recommends that the library system of people, places, collections and services—or what is referred to as the library/ian—be designed to support and energize academic learning, service learning, and social and emotional support for the community. The library/ian should be directly represented in curriculum planning and development in the school community.

—

The IB Programme standards and practices (2018 and updated 2019) requires the school to maintain a functioning and active library consisting of adequate combinations of people, places, collections and services that aid and extend learning and teaching (p. 8).

See Australian School Library Association Recommended Minimum Information Services Staffing Levels (2020).

—

References

IBO. (2018). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organisation.

IFLA School Library Guidelines (2015)

Sinek, S. (2009, September). How Great Leaders Inspire Action. Retrieved from TED: https://www.ted.com/talk/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action

Tilke, A. (2011). The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program and the School Library: Inquiry-Based Education. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

27th April 2021 at 4:06 pm #49117Thank you so much Darryl. I need to read and digest this properly and will the share the business case I write for SG (SLT) as soon as I’m happy with it.

27th April 2021 at 5:58 pm #49144A pleasure, Ruth.

I should have added that the IFLA Guidelines elaborate on the first distinguishing feature at some length (pp. 38-45), identifying the core instructional activities that constitute the school library’s pedagogical programme as:

- literacy and reading promotion (pp. 39-40)

- media and information literacy (MIL), which may be developed within the chosen model of the inquiry learning process (pp. 40-41)

- inquiry-based learning, which may include the development of MIL skills within the chosen model (pp. 41-44)

- technology integration (p. 44)

- professional development for teachers (p. 44)

“School librarians recognize the importance of having a systematic framework for the teaching of media and information skills, and they contribute to the enhancement of students’ skills through collaborative work with teachers (p. 8) … These [inquiry and lifelong learning, self-directed learning (i.e., metacognitive), and collaborating] skills are best developed progressively within a subject context, with topics and problems drawn from the curriculum” (p. 42).

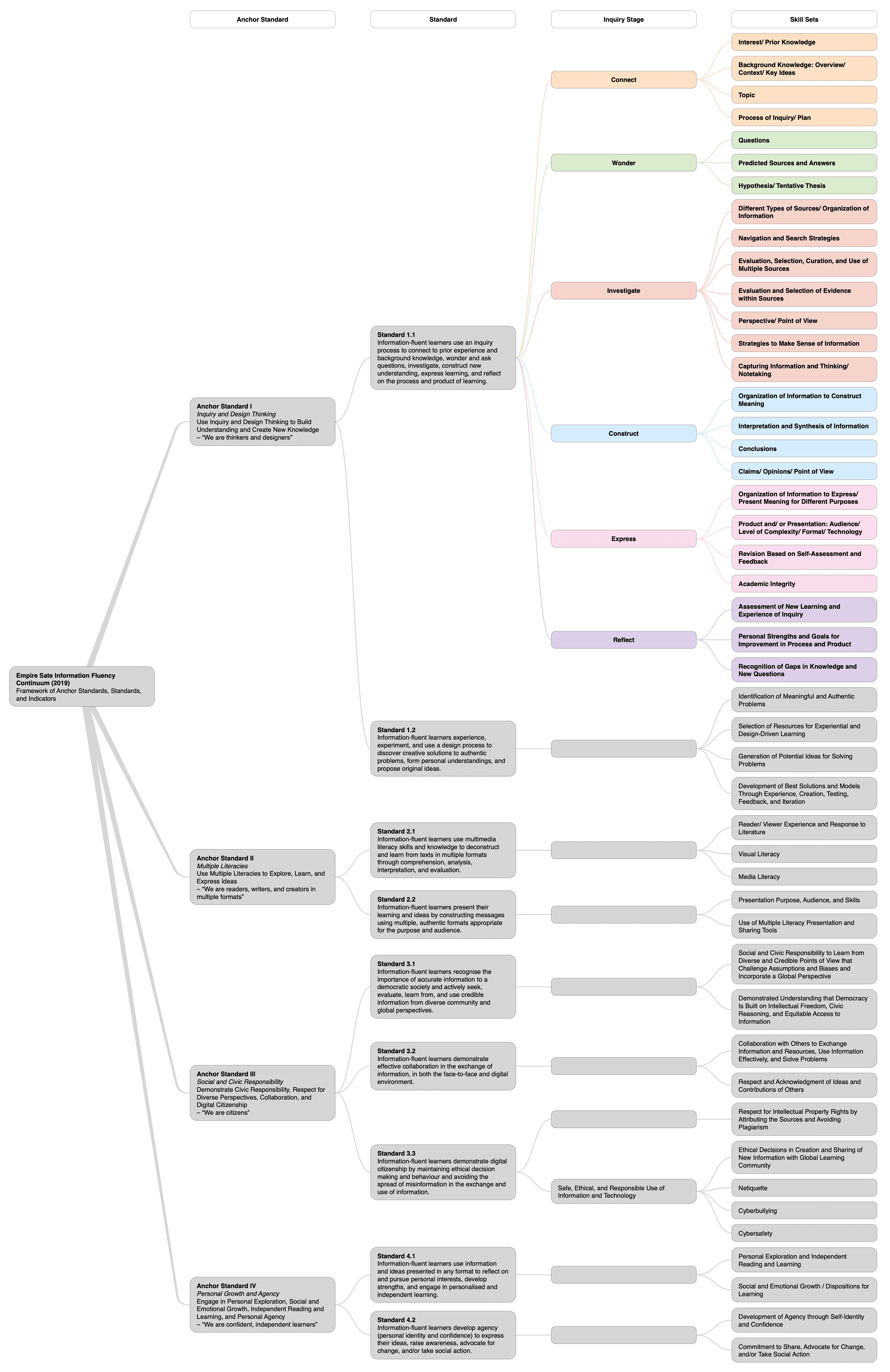

This makes FOSIL – as a sound instructional model of the inquiry learning process undergirded by a detailed framework of skills covering Inquiry & Design Thinking, Multiple Literacies, Social & Civic Responsibility, Personal Growth & Agency (ESIFC, 2009 & 2019) – a compelling choice, I think.

More broadly, I am beginning to understand that FOSIL in its fullest sense addresses all 5 of the core instructional activities of the school library’s pedagogical programme as outlined in the IFLA Guidelines.

28th April 2021 at 8:57 am #49316A ‘final’ consideration is the link between school libraries/ librarians and student achievement. A helpful article is Why school librarians matter: What years of research tell us, by Keith Curry Lance and Debra E. Kachel (March 26, 2018) in Phi Delta Kappan.

However, references to this article are often misleading.

The positive correlation demonstrated since 1992 by the library impact studies is between “high-quality library programs and student achievement”. While Lance and Kachel state that “the mere presence of a librarian is associated with better student outcomes,” which extend beyond student achievement, this is still in the context of the school library program (i.e., what the school librarian does).

The context of the school library impact studies is specifically American, although they are instructive. As Lance (2019, p. 50) writes in “Last Lecture” Remarks about the Current Status and Future of School Librarianship and School Library Research (in Symposium of the Greats: Wisdom from the Past & A Glimpse into the Future of School Libraries, edited by David V. Loertscher and Blanche Woolls):

Ironically, while most of us understand the profound limits of standards–based testing—not to mention the devastating toll it has taken on U.S. public education—it is a simple fact that a quarter–century of impact studies would not, and could not, have happened had it not been for the ubiquity of such testing and the high stakes put on their results. Except for their ubiquity, the data necessary for the research would not have existed. Except for the high stakes, nobody would have cared enough to bother funding research like ours.

This, in my opinion, is the real value of the IFLA Guidelines, which is that they apply the lessons of the school library impact studies to an international research context stretching back over 60 years.

The key point, then, is that the distinguishing features of a school library as outlined in the IFLA Guidelines – professional and paraprofessional staffing levels appropriate for the size of the school and its unique needs, delivering a high-quality pedagogical program based around the core instructional activities, supported by targeted high-quality diverse collections, and subject to an explicit policy and plan for ongoing growth and development – are the optimal conditions for the school library to produce said positive correlations with student achievement, and related desirable outcomes.

It is fine if we – individually and/ or collectively – do not yet have all of this, but it is vital to our success that we be clear about what we need to be striving for.

10th May 2021 at 1:07 am #52471As a school we are working through the consultation for the school plan 2026, the vision for the next 5 years of education. Staff have been asked for comments and given the opportunity to take part in discussions that are intended to help form the vision for the next 5 years. I saw this as an opportunity to suggest that we embed FOSIL.

One of the questions we were asked is ‘If you were choosing a school for your child in 2030 what would it look like’. This made me smile because my comment when I heard about Darryl’s move to Blanchelande College was that I would choose a school because it had implemented FOSIL across the board.

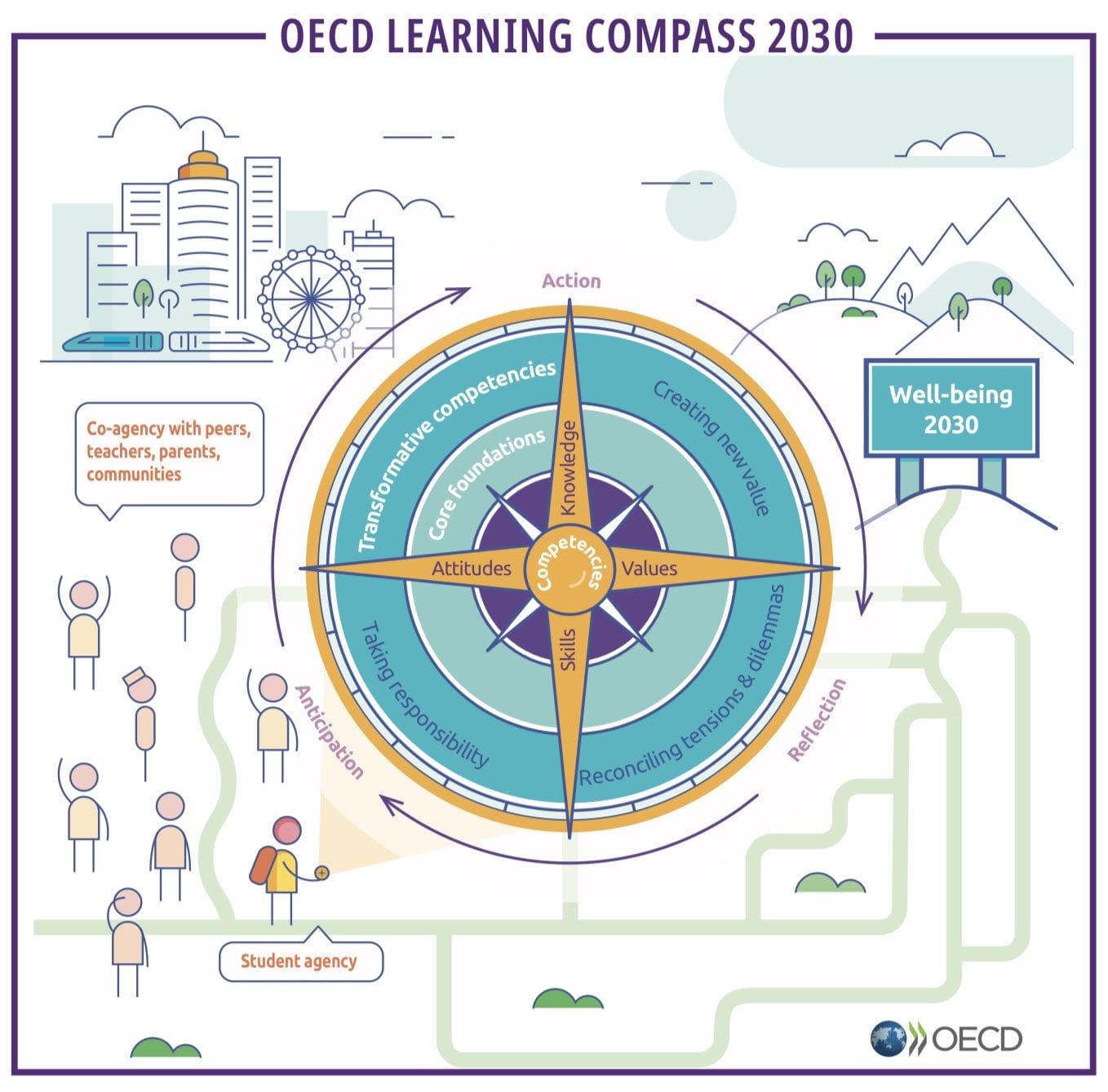

In the presentation we were asked to consider the OECD’s future of Education and Skills 2030 project. If you haven’t come across this it is well worth investigating. Central to the explanation is the Learning Compass (OECD, 2018) which they describe as giving the students ‘agency; the capacity to set a goal, reflect and act responsibility to effect change. To act rather than be acted upon.’

Data and digital literacy is one of three core foundations and the whole compass of competencies is developed through a ‘cyclical learning process; anticipating, acting and reflecting’ (AAR). I wonder if this is beginning to sound familiar? Apologies if I’m teaching my grandmother to suck eggs but I didn’t come across any other mention of this on the forum.

The Anticipation part of this process is going further than Connect. ‘Anticipation requires more than just asking questions; it involves projecting the consequences and potential impact of doing one thing over another, or of doing nothing at all’ (OECD, 2019) which gave me cause to question whether this is a development of connect or something broader. Are we asking for a level of anticipation when students connect? Should they be anticipating outcomes or is this in danger of narrowing their inquiry? I like the idea of anticipation, particularly if it conscious, that is to say that part of the connect process is to exercise conscious anticipation and consider what students anticipate as being the outcome of their inquiry and how that might influence their investigation.

AAR is designed for a wider approach to education than teaching based inquiry, it seems to be an approach to action across students’ lives ‘A key aspect of the anticipation phase of the AAR cycle is the ability not just to respond to current events but to anticipate future events’ (OECD, 2019). However, it seems that there is a connection to be nurtured here and obvious parallels to be drawn.

The OECD state that the AAR cycle is a catalyst for the development of student agency ‘… defined as the capacity to set a goal, reflect and act responsibly to effect change. It is about acting rather than being acted upon; shaping rather than being shaped; and making responsible decisions and choices rather than accepting those determined by others.’ This idea brought to mind the discussions, held elsewhere on the forum, about ‘FOSIL is Learning by finding out for yourself (not by yourself, which suggests minimal or no guidance and/ or interventions’ (Toerien, 2021). I think there is a connection here; the agency to find out by yourself, to effect a change in your knowledge rather than having that change imposed upon you by a teacher who tells students rather than leads them to inquire.

I will certainly be using this as leverage, not only in my case for an apprentice (which I’ve attached here but have not had feedback on) but also as a means of influencing the school’s strategic plan and vision for 2026.

Attachments:

10th May 2021 at 2:03 pm #52641Thank you so much for sharing this, Ruth, and hoping for the desired outcome.

I include the OECD Learning Compass for reference below:

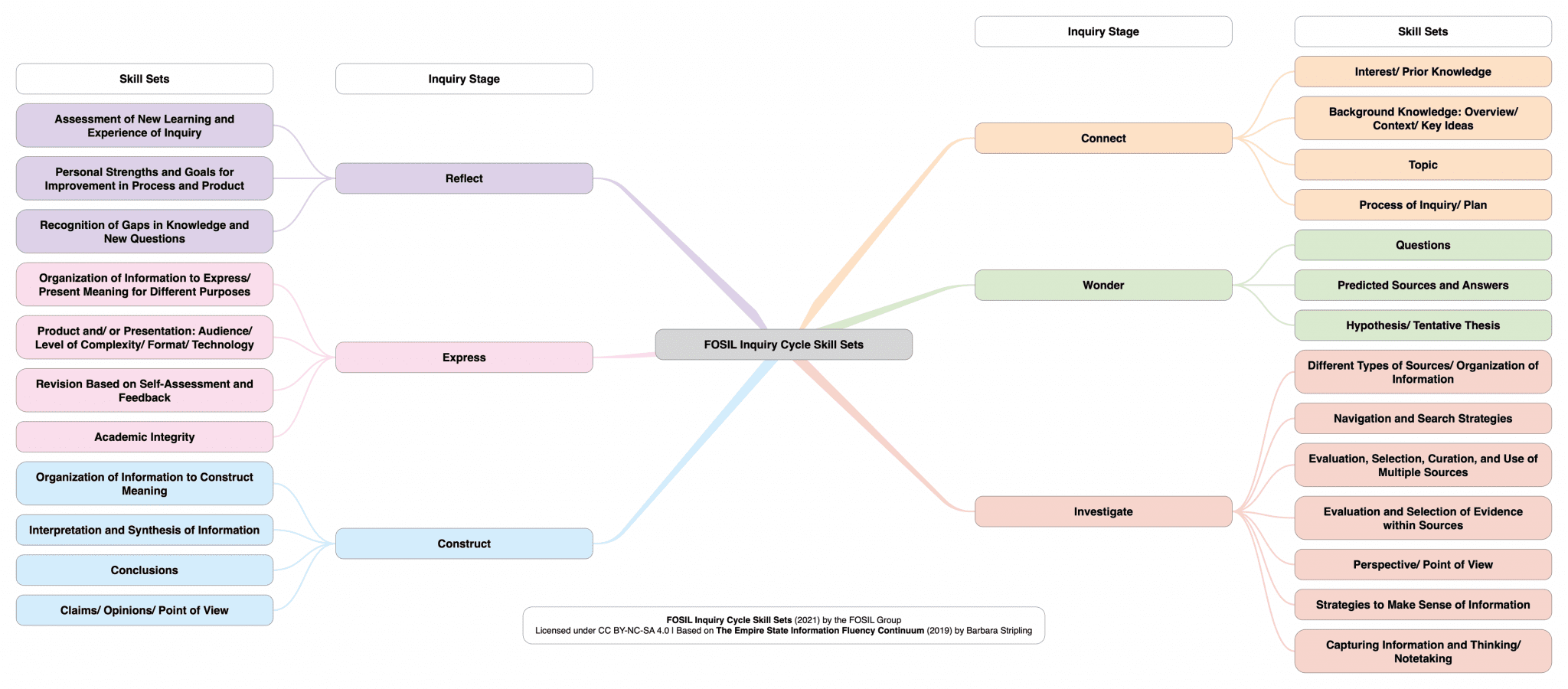

Regarding your question about Anticipation and Connect, I would say that Anticipation encompasses Connect and Wonder, which is clear from the FOSIL Inquiry Cycle Skill Sets (see below):

Also, bearing in mind that inquiry is only one of the standards in the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum (see below), the complementarity becomes quite striking (download as PDF):

- It has a qualified school librarian with formal education in school librarianship and classroom teaching that enables the professional expertise required for the complex roles of instruction, reading and literacy development, school library management, collaboration with teaching staff, and engagement with the educational community.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.