Portraits of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › Portraits of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer

- This topic has 3 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 2 years, 3 months ago by

Barbara Stripling.

Barbara Stripling.

-

AuthorPosts

-

22nd June 2022 at 12:33 pm #79022

This topic will accompany and elaborate on the latest in my series for The School Librarian, the quarterly journal of the UK School Library Association.

See here for the series so far.

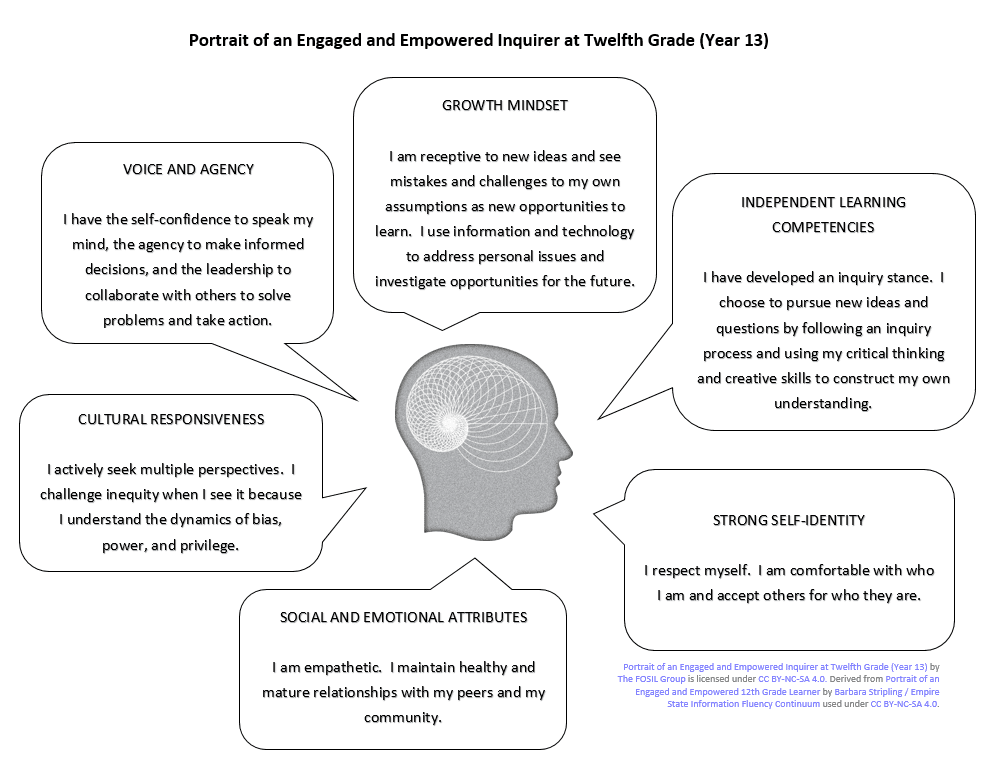

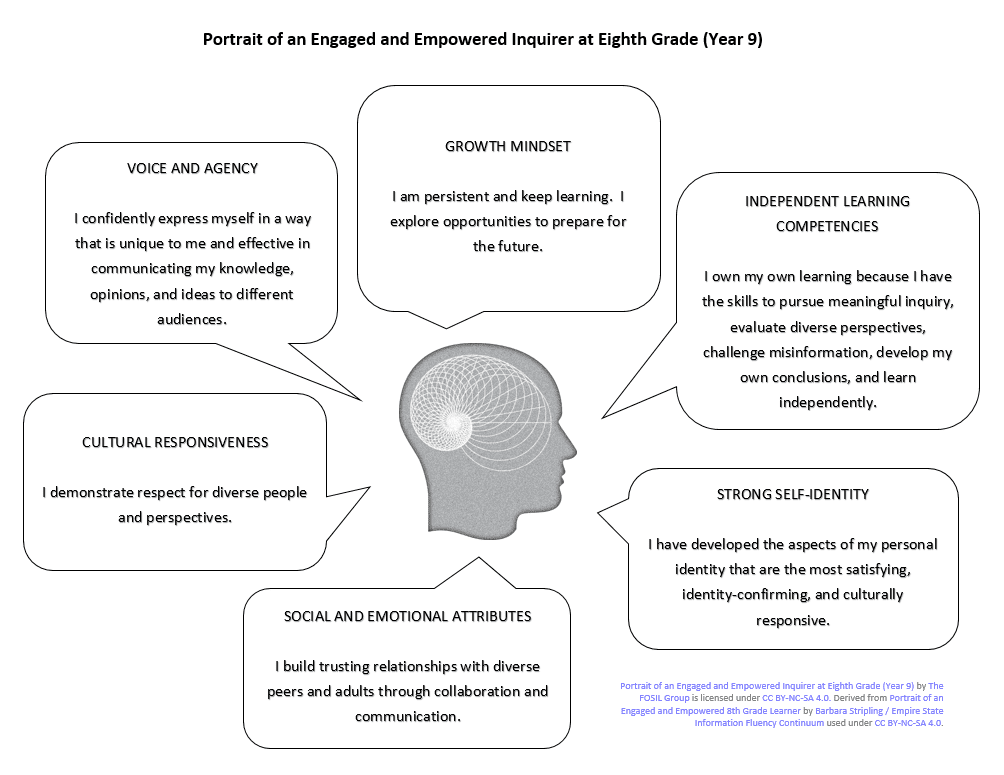

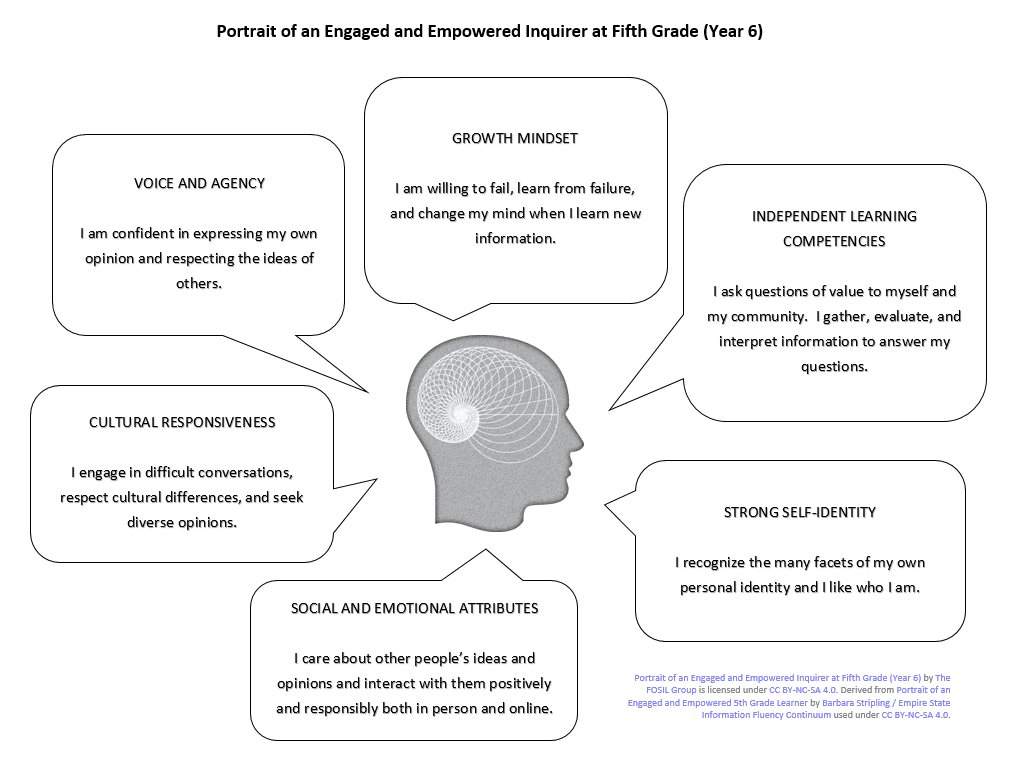

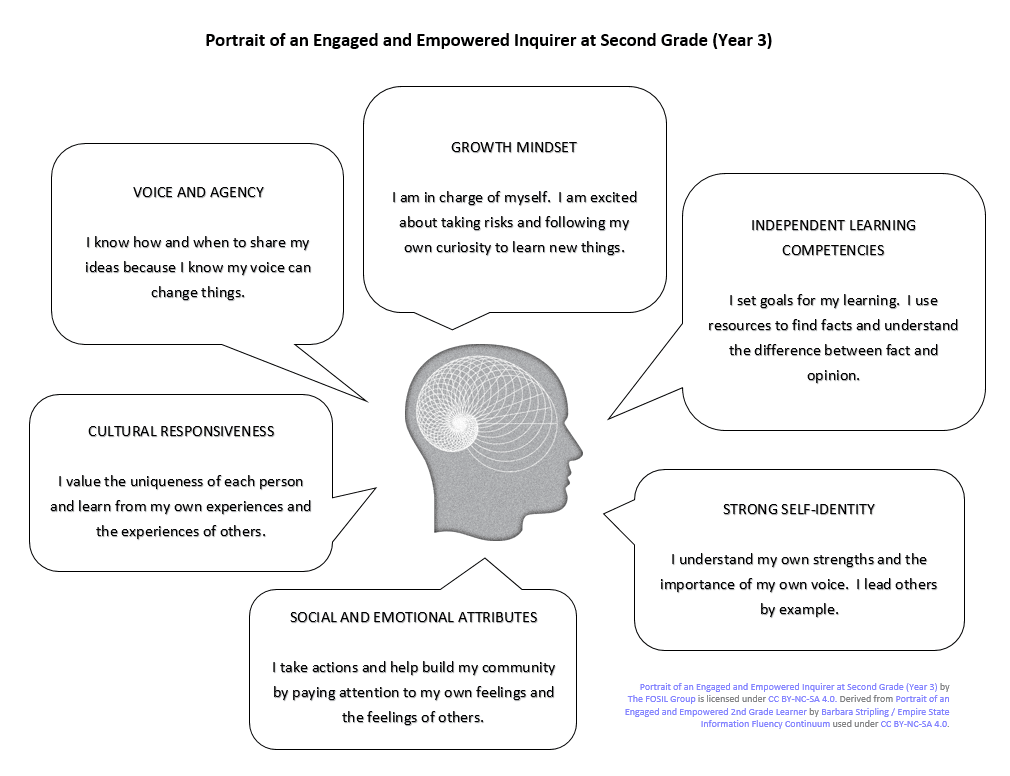

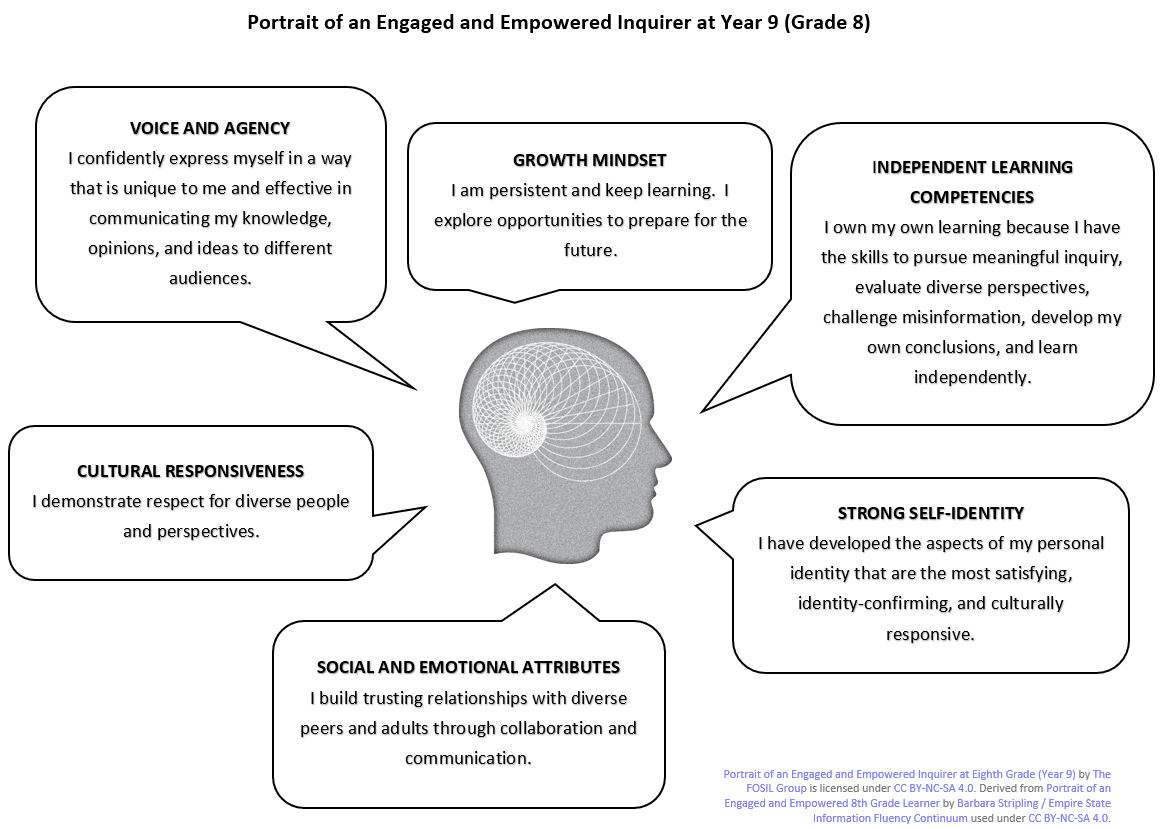

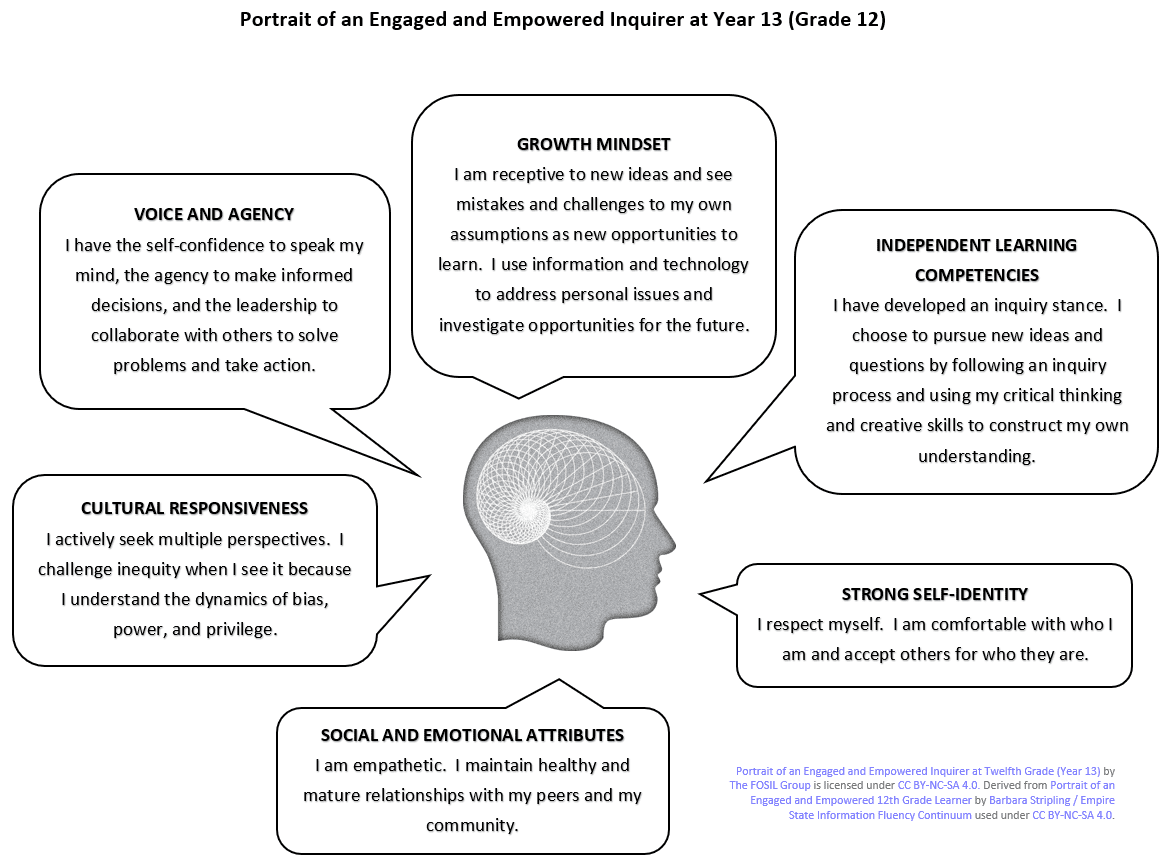

12th July 2022 at 11:04 am #79054As I wrote in The School Librarian, Volume 70, Number 3, Autumn 2022 (see here), inquiry, and in our case FOSIL-based inquiry, has the Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Twelfth Grade (Year 13) as its end (see Figure 1 below) and is the systematic and progressive means to this end (see Figures 2, 3 and 4 below).

The Portraits were developed by Barbara Stripling and Digital Lead Librarians in New York City, and are a profound statement on the educational process from the perspective of a school library integral to that process.

Figure 1: Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Twelfth Grade (Year 13)

Figure 2: Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Eighth Grade (Year 9)

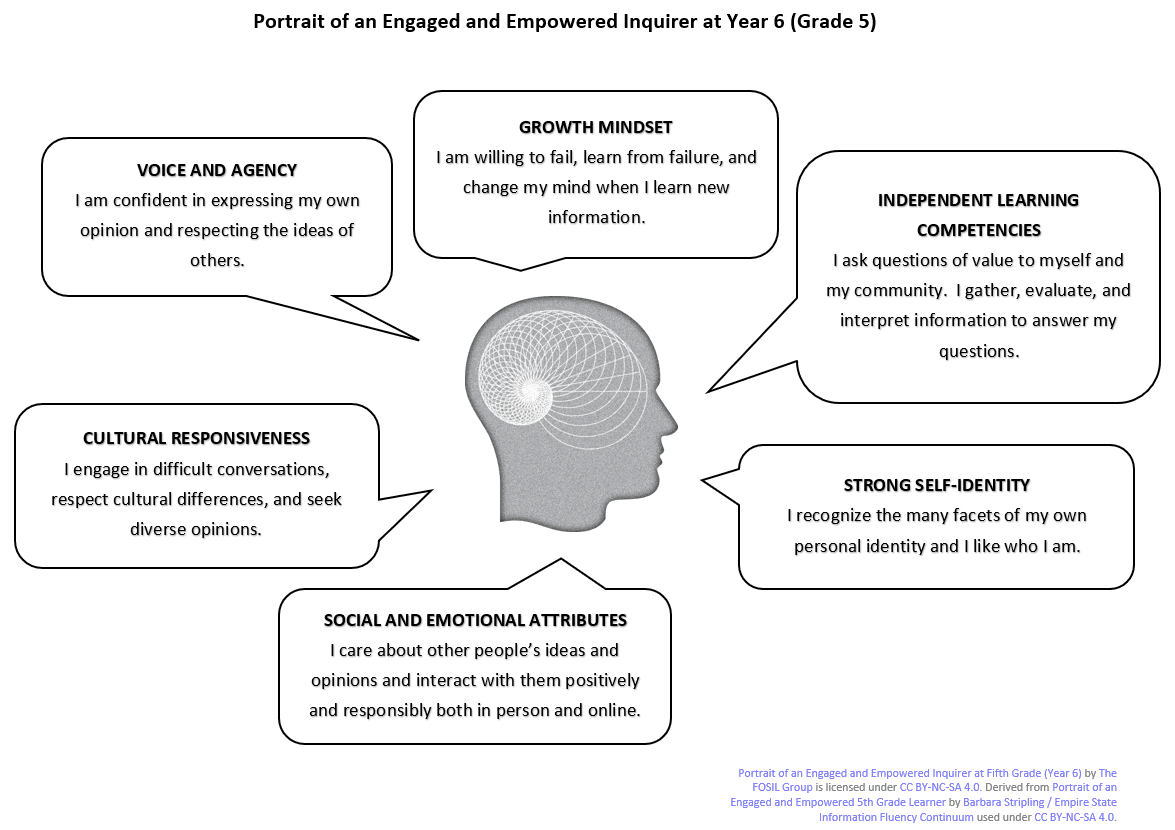

Figure 3: Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Fifth Grade (Year 6)

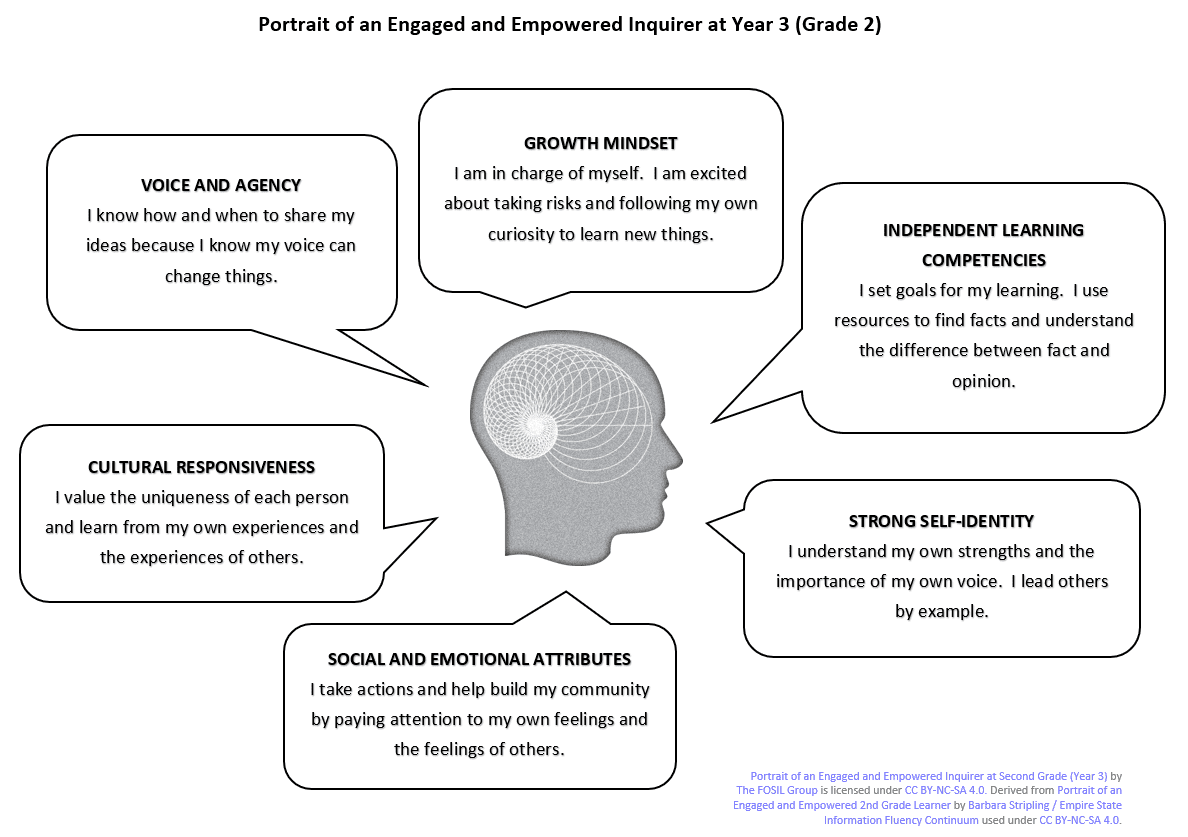

Figure 4: Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Second Grade (Year 3)

28th October 2023 at 1:03 pm #81678Edit (2023/10/30): I have added links to the revised graphic organisers and have also added PDF downloads.

—

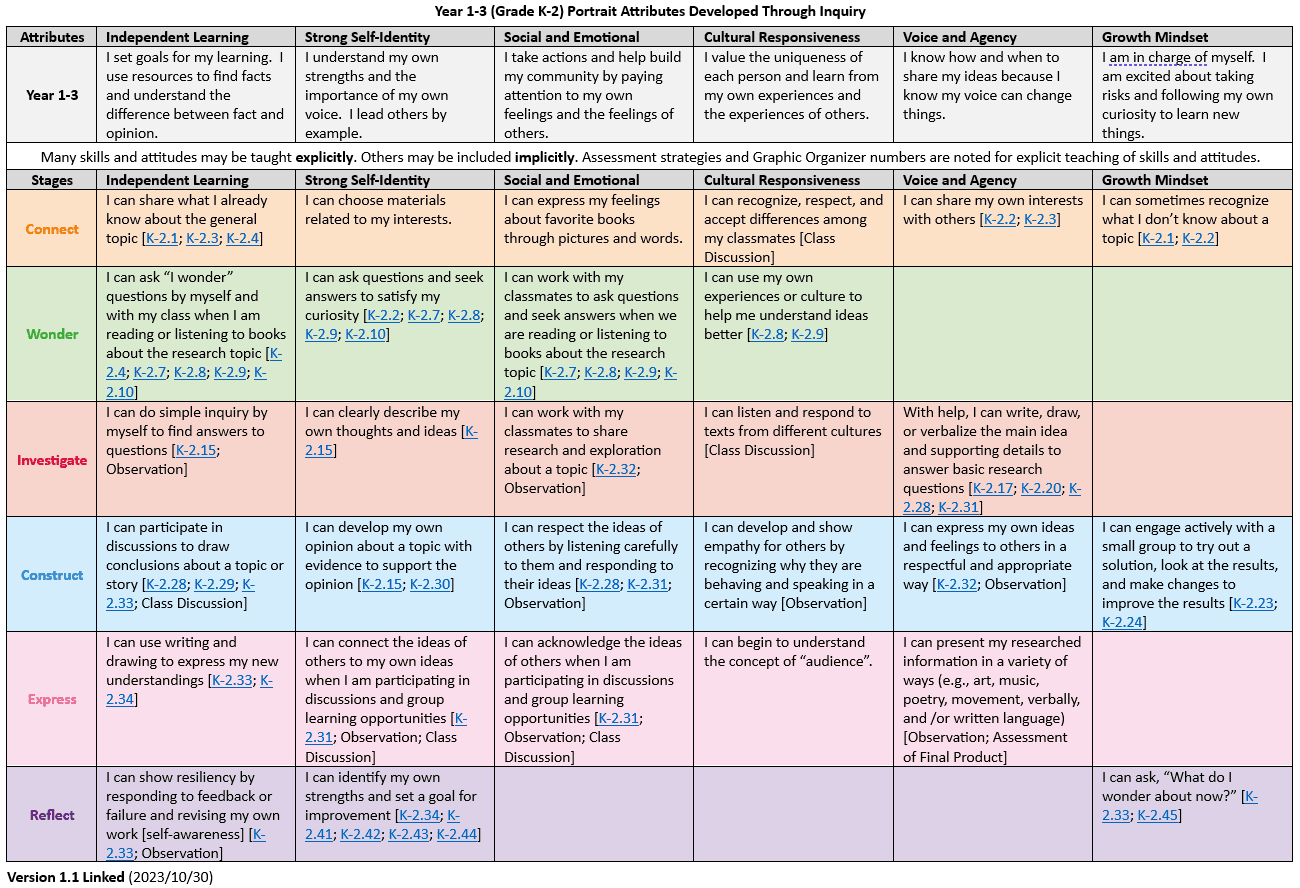

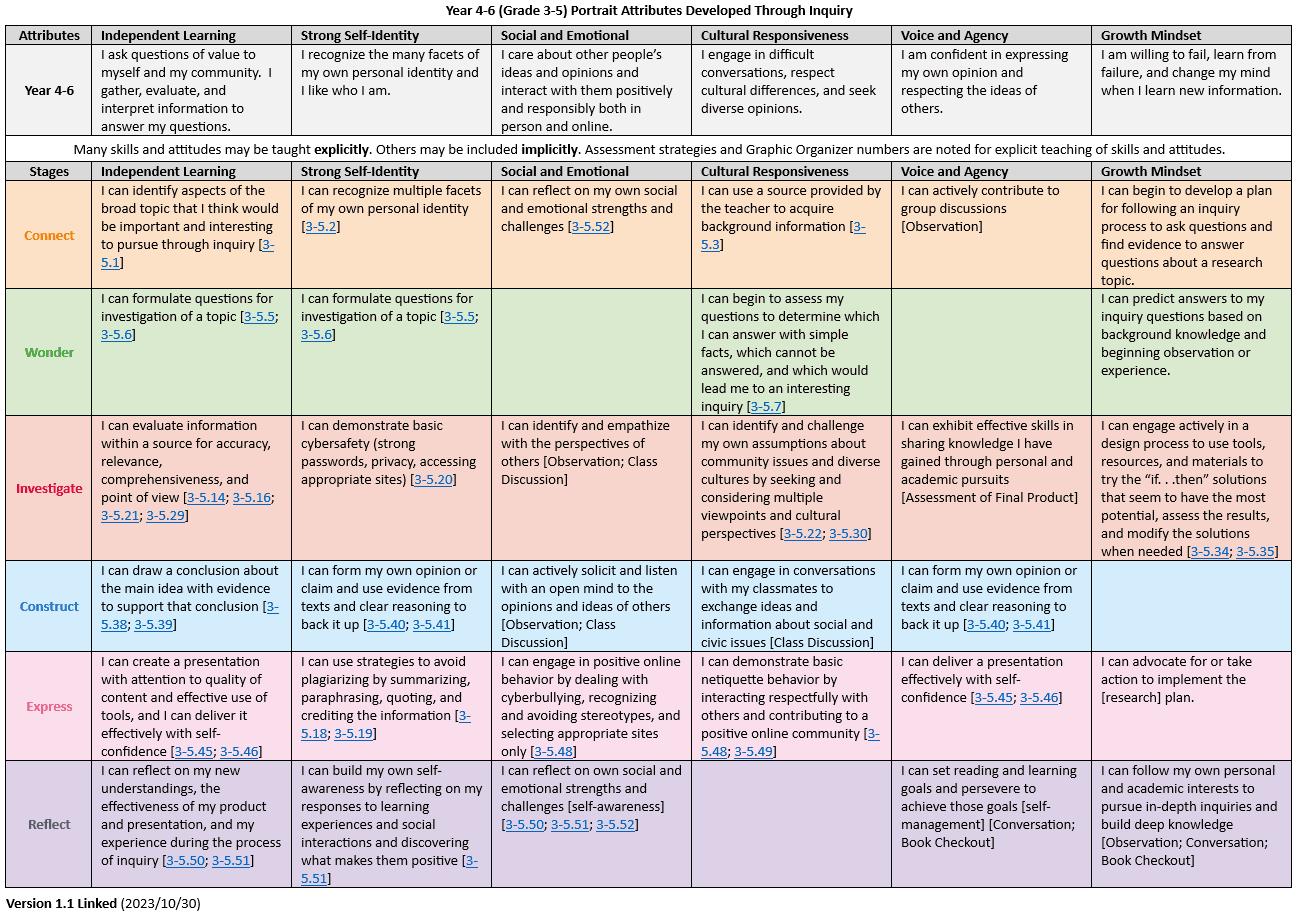

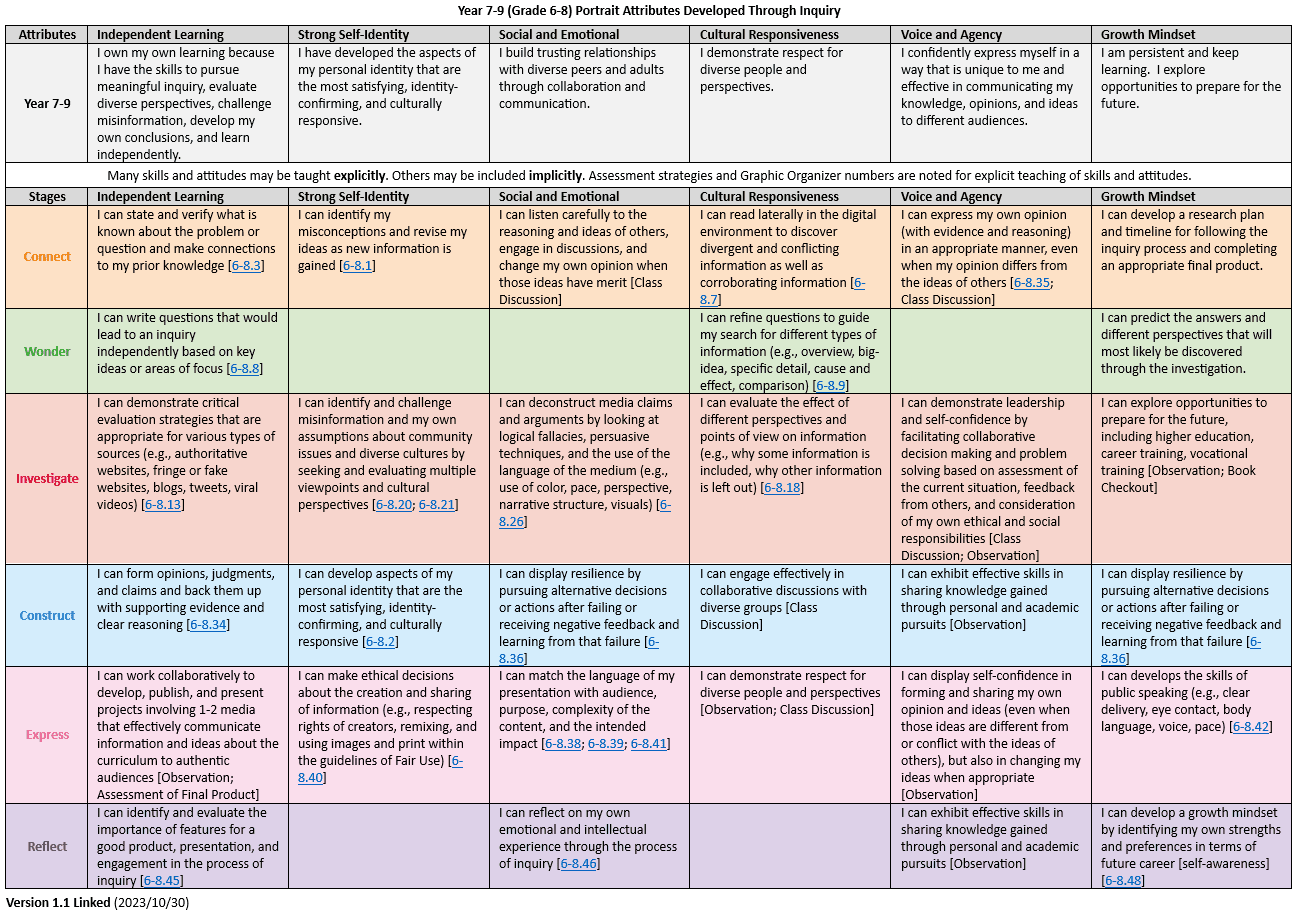

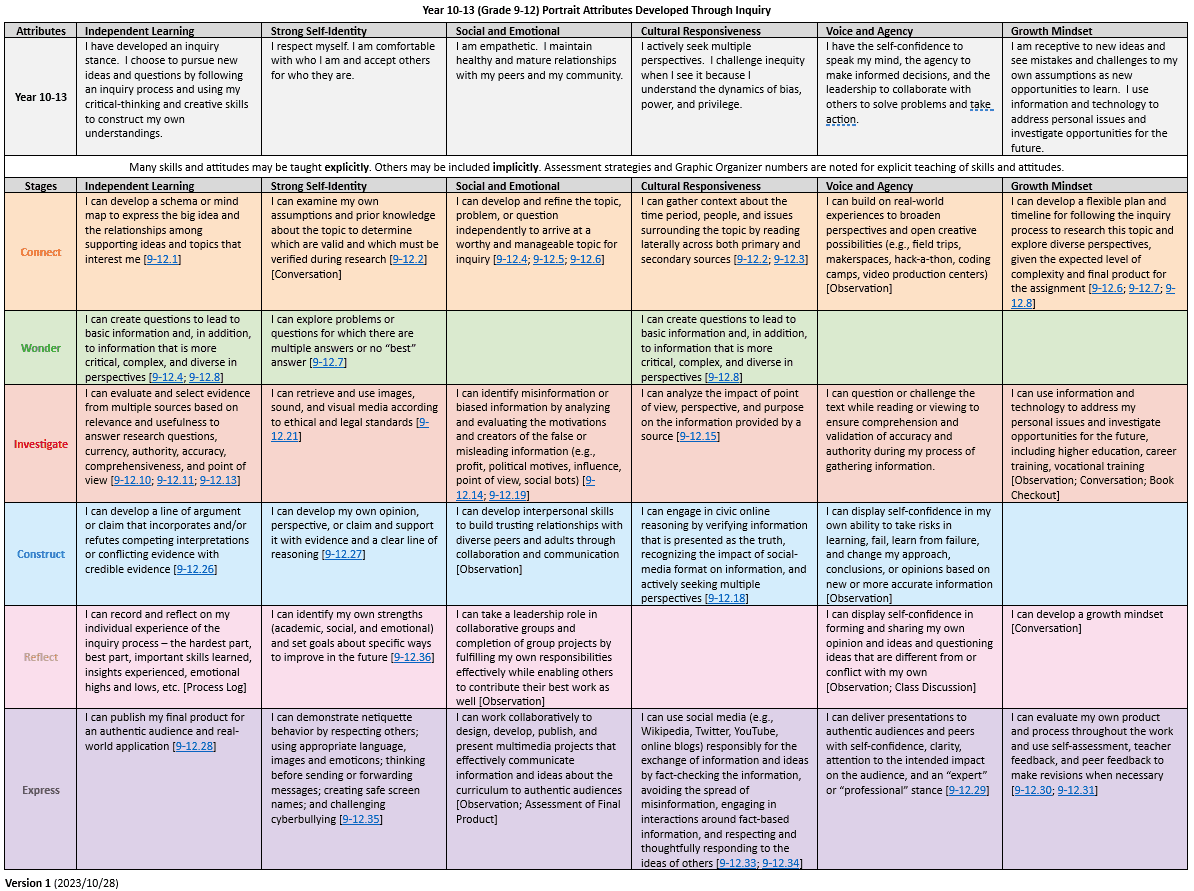

I include below the next stage in the development of the Portrait of an Engaged and Empowered Inquirer at Years 3, 6, 9, and 13, which are the typical Portrait Attributes Developed Through Inquiry in Years 1-3, 4-6, 7-9, and 10-13.

I will elaborate in due course.

Portrait Attributes Developed Through Inquiry in Years 1-3 (PDF download).

Portrait Attributes Developed Through Inquiry in Years 4-6 (PDF download).

Portrait Attributes Developed Through Inquiry in Years 7-9 (PDF download).

Portrait Attributes Developed Through Inquiry in Years 10-13 (PDF download).

1st November 2023 at 8:25 pm #81723

1st November 2023 at 8:25 pm #81723One of the reasons that I started developing the portraits is that I believe, first, that we (school librarians, classroom teachers) must always focus primarily on our students and their intellectual, social, and personal growth (rather than the library or library collection). That learner filter enables me to make good decisions about the library program, resources, and instruction. Secondly, I know that I need to be able to envision the learners I am trying to “create” in order to plan and implement a library program that builds students through a continuum of development. What does a second grader who has developed essential skills and attitudes look like? What is my role, as a librarian, in provoking and nurturing that development?

I have been pursuing my understanding about inquiry-based teaching and learning through the library for the last twenty years. My work on developing an inquiry process and a PK-12 continuum of skills (entitled the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum – ESIFC) has continued to be modified, adapted, and deepened as my own understanding has become more complex and nuanced. Two years ago, I worked with a group of stellar librarians in New York City to update the ESIFC and align it with new NY digital fluency standards and a new framework of cultural responsiveness. Hard work, but we shared our revised ESIFC and graphic organizers online through a Creative Commons license (https://slsa-nys.libguides.com/ifc).

As I was facilitating that work, I realized that my philosophy about the librarian’s role in teaching and learning through the library had changed. I believe that school librarians must accept the responsibility for teaching the whole child – the critical and creative thinking skills of inquiry and literacy (independent learning), but also the whole-child attributes of self-identity, social and emotional strengths, cultural responsiveness, voice and agency, and a growth mindset. The group of NY City librarians did initial work on defining the whole-child attributes for grades 2, 5, 8, and 12. Those grades were selected because, in the United States, they are benchmark points in a child’s educational experience. I have continued the work and have developed a comprehensive alignment of specific skills and attitudes for each of the portrait attributes with the six stages of my inquiry process – Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express, Reflect.

All of those skills were already embedded in the ESIFC, but by explicitly listing them under their appropriate portrait attribute, we can see how we can teach a lesson to middle schoolers focused on Connect, for example, to enable students to state what they already know or assume about the problem or question (independent learning), and, during the same lesson, enable them to identify their own misconceptions (self-identity), understand how they personally connect to the topic (voice and agency), and discover different perspectives on the same topic (cultural responsiveness). It sounds a bit complicated, but many (most?) lessons we already teach touch on those personal attributes. With an intentional portrait focus, we can be explicit and let the students know how many skills and competencies they are learning beyond the content.

Because my goal is to engage and empower student inquirers, I wanted students to recognize their own empowerment. The next step, then, was to develop “I can” statements for each of the attributes. I think those “I can” statements can be shared with students before inquiry experiences, so that they recognize the skills they will develop through their own active learning. Typically, in the United States, students are told the content goals before a unit or lesson, but little mention is made of the skills they will develop. The “I can” statements turn the responsibility for learning over to the students and give them a picture of success.

I plan to continue devcloping tools and strategies for whole-child teaching guided by the portraits. I know I will continue collaborating with Darryl and Jenny to provide models of units and lessons for others to adopt and adapt. We are interested in your own reactions to this work and your thoughts about next steps.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.