ChatGPT et al

Home › Forums › The nature of inquiry and information literacy › ChatGPT et al

- This topic has 29 replies, 6 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 1 month ago by

Darryl Toerien.

Darryl Toerien.

-

AuthorPosts

-

11th May 2023 at 12:38 am #80345

Hello everyone!

What an incredibly informed and balanced discussion of ChatGPT and its ilk! I have really enjoyed reading these posts and will be following up on many of the links shared.

I agree that it is concerning that there seem to be two extreme responses to this evolution; head in the sand or jumping in the deep end. What I am most concerned about is the way that so much conversation centres around ChatGPT as it exists today. While it is great that some teachers are taking the intiative and playing in this space, to spend extensive time designing very specific ways to use the tool seems to me to be missing the point…that the free iteration of ChatGPT we are working with is just a very brief pitstop along the way. I’m definitely not suggesting we avoid using the tool completely – however I’d rather the debate, time and energy be devoted to the bigger picture – taking a step back to ask ‘how might this evolving technology impact not just single lessons or assessment tasks, but teaching and learning in general?’ ‘What are the ethical implications of using these tools and how do we prepare our students (and fellow teachers) to use them in an informed and balanced way?’ ‘What are our responsibilities as educators to walk the line between building students’ skills in using technologies and building students’ capacities to problemsolve and think deeply and critically without technologies (e.g. exercise their human brains rather than their digital brains)?’

There may not even be answers to these questions, and I believe having read your discussions that you are all thinking along the same lines, but I do think this is where the Teacher Librarian/School Librarian can really take a leading role – being freed to encourage the bigger picture thinking that teachers who are tied down to specific curricula may not have as much opportunity to undertake. It seems to me that AI is not something we will become competent in – we will never understand what’s happening inside the black box – but it is something we can encourage a spirit of inquiry about, and an ongoing questioning and challenging rather than just accepting everything presented at face value.

That’s just my personal thinking at this stage. I’m hoping to initiate some research, and have been asked to write and present on this topic, so I am really looking forward to learning more, and have already learnt from your generously shared thoughts in this forum!

My colleagues and I will be attending IASL in Rome, and I’m really looking forward to meeting you in person and having some great chats about this and other school library related topics – I think we can build a strong international network :).

Warm regards,Kay.

20th May 2023 at 5:03 pm #80506Hi Kay, thank you for your thoughtful contribution. It’s a real pleasure to welcome you to the FOSIL Group community. Please do subscribe to our all forums to receive notifications of new posts. We also look forward to meeting you in Rome.

Thanks Kay and Elizabeth for flagging Barbara Fister and Alison J. Head’s excellent article on ChatGPT.

I found myself largely in agreement with most of what they said but it did remind me of something that has been in the back of my mind for a while. In all the comparisons with Wikipedia, we need to be very careful of statements like “Even the most strident critics eventually came around. Wikipedia gained recognition in campus libraries as a tertiary source”, which imply that Wikipdedia was always fine and once we all stopped being so hysterical about it and looked at what it actually was, we realised it was actually pretty good and started to integrate it into teaching and learning. That does ignore the fact that Wikipedia got a lot better over the years.

It’s worth winding back through the ‘history’ of some of the early articles to remind ourselves of this. Even in 2008 there were long articles on important topics with just a few references – as an example, I looked through the President of the United States article history (one of the Wikipedia features I do really like):

- The article was first written in September 2001

- It got its first dedicated ‘References’ section in November 2007 (there had been a variety of iterations of external links, notes, further reading, footnotes and notes and references sections before that but nothing substantial), but it was pretty sparse.

- The first time a “this article needs more citations” banner appeared was on July 19th 2008, at which point the 5,200 word article had just 19 citations (274 words per citation). By comparison today’s article has 195 citations for an article with around 10,600 words (54 words per citation).

As Fister and Head acknowledge, at a certain point scientists and academics also started to actively engage with Wikipedia to help to improve the articles.

My point is that Wikipedia has got a lot better (perhaps closer to the more traditional encyclopaedia), which is why we can now – with caveats and reservations – include it in teaching and learning to an extent that would not have been sensible for about the first ten years. It does still have serious limitations as anything other than a tertiary source. As its founder Jimmy Wales famously said in 2006 “For God [sic] sake, you’re in college; don’t cite the encyclopedia.”. For younger students (for whom citing an encyclopaedia might be appropriate) the content is just not written at an age appropriate level. In making this guide to Britannica School for a Year 7 (11-12 year olds) group this week I was reminded just how flexible and accessible it is for different age groups (click the arrows to scroll through the slides). Wikipedia does have its place, but I’m not sure how often it is actually a student’s most useful first port of call – and never their last.

I agree with Kay 100%. There is little point handwringing about how awful AI is and that it should be banned in educational settings based on how it manifests right now. It is bound to change and get better and objections based purely on how often it is wrong (which at the moment seems to be quite a lot!) will fall away. Equally it would be crazy to jump in and embrace it fully and enthusiastically without criticism, and not just because in its current incarnation it is flawed.

Kay is right that our focus needs to be on the big questions. Under the surface, the rapid evolution and adoption of AI has very serious ethical, moral, social and legal issues (and some particular ones related to largely being a proprietary technology, where corporate vested interests are always going to be an issue) which we as Librarians are ideally equipped to wrestle with. It is also likely to change the educational landscape hugely, just as the growth of the internet did. I left school just as the internet was really getting started in the mid 1990s, and my experience of education was quite different from students’ experiences today – and changes have generally been for the better I think.

I do think that discussions of Wikipedia are a distraction here (and Fister and Head point out that social media was arguably a much bigger influence in society than Wikipedia was). Wikipedia did not cause massive educational shifts because the information it carried was already ‘out there’ on the internet, it was just an (arguably for some) more convenient package. AI has the potential to cause seismic shifts because, while it is still working with information which is publicly available (as far as we know) it has the ability to endlessly synthesise and repackage that information to suit different agendas and voices. It is designed to give us what we want, even if that involves making stuff up. And what we want is not always what we need.

The challenge is going to be that this shift is likely to happen very rapidly. Almost certainly more rapidly than the original impact of the internet on education, in part because the connectivity is already there. Most people have internet enabled devices, and the vast majority of schools in the developed world certainly do. AI is, on the surface, fairly intuitive so everyone can have a go – and children are notoriously good and enthusiastic adopters of new technologies but, as any Librarian teaching search skills and source evaluation will tell you, they are generally not nearly as good as they think they are.

So if we have big questions to address about how AI will impact education and how we need to adapt to prepare children for an increasingly AI integrated world (with all the many complex issues that brings), then we need to act quickly. This is a debate about education and society, not about one particular technology or manifestation of that, and Librarians need to push to get a seat at the table, both as educational leaders plan for the future of education, and as leaders more broadly plan and legislate for the future of society. We absolutely need to be part of those conversations in our schools, with leaders, teachers and students (neither as doomsayers or cheerleaders but as voices of reason!). But we need to think beyond that as well.

I was powerfully reminded of that this morning when I woke up to an article in The Times entitled “AI ‘is clear and present danger to education’: School leaders announce joint response to tech“, which announced that a group of educational leaders led by Dr Anthony Seldon (historian and author, currently head of Epsom College, and formerly Brighton and Wellington Colleges) wrote a letter to The Times stating that:

“AI is moving far too quickly for the government or parliament alone to provide the real-time advice schools need. We are thus announcing today our own cross-sector body composed of leading teachers in our schools, guided by a panel of independent digital and AI experts. The group will create a website led by heads of science or digital at 15 state and private schools. It will offer guidance on the latest developments in AI and what schools should use and avoid.”

It really struck me that Librarians are not mentioned at all here (school librarians in the UK are not viewed as specialist teachers, so would not be included in the phrase ‘leading teachers’ as they might be overseas), and we need to be pushing for a voice in projects like this. This is the task, and we need to set our sights high. We absolutely need to be part of those conversations in our schools, and I’ve heard some wonderful stories of school librarians using the opportunities provided by a new technology that has unsettled some in their schools to get out into classrooms to offer their expertise. But that is not enough. AI has some serious and disturbing implications (as well as exciting opportunities) for education and for society and we need to explore these fully, take an informed position and make our voices heard as educators AND information professionals before others shape the future for us, and we are left on the sidelines, trying to justify our place in the new educational landscape rather than being part of shaping it.

22nd May 2023 at 1:41 am #80524Jenny, your final observation regarding the importance of school library staff to take an active role in discussions regarding AI is central to this discussion. School library staff have always taken an leading role in the introduction of new technologies in education, and the synergy created through expertise in both education (pedagogy, curriculum etc) and information management positions us as leaders in this area. The skills and knowledge of school library staff is super-charged by the fact that potentially more so than any other educator, they work with students and teachers at every year level, and across all subjects – a ‘birds-eye view’ of the curriculum and the school community that enables new and informed insights.

23rd May 2023 at 7:46 am #80528Thanks Kay. I absolutely agree with you that school librarians are ideally placed to be at the centre of this discussion – and hopefully that that is happening in Australia. In the UK (where school librarians are not regarded as specialist teachers, there is no consensus on the qualifications they should have and in many schools they are regarded as support staff not teaching staff) it is certainly far from the case at the moment and is something we need to fight for. While I am sure there are many challenges facing of the profession in Australia too, as an international community we are so much stronger because we can learn from (and point to) best practice all over the world.

10th June 2023 at 1:49 pm #80682I just wanted to take the opportunity to share my latest podcast AI: Friend or Foe. The School Librarians Perspective. I was joined by Darry and Jenny Toerien and Dr Kay Oddone. I hope you find it adds to this very interesting conversation.

5th December 2023 at 11:30 am #81983Hi everyone,

I have yet to catch up with this conversation fully I’m afraid. (thanks for the tip about subscribing, that will help me hugely)

However, I wanted to share this quote from The Department for Education’s GenAI in Education Summary of Responses to their Call for Evidence. (Thanks to Elizabeth Hutchinson for sharing)

‘The most requested training topics were basic digitalliteracy, AI literacy, safe and ethical GenAI use, alignment of GenAI with goodpedagogical practice, and how to prepare for GenAI’s impact on the skills students willneed as they enter an AI-enabled workforce.’ (Pg.30)

‘The most requested guidancetopics were addressing academic malpractice, safe and ethical use, and data privacy and protection.’ (Pg 30)

This makes me want to sing and cry. This is Librarians and our expertise, are we in these conversations at DfE level, with EduTech or others thinking at this level? I was very sad to see no Libraians on the panel for Ai in Education

Of course it is possible that I am working in a small world and have’t raised my head to see who’s doing what. Are we involved and if not how can we have our voices and experience heard?

Surely this is our momnet, the time when we can truely demonstrate the value of a Librarian beyond reading for pleasure. I am lucky in my school to have been asked by the Head to start the school’s working party on AI (Yes, we are a way behind others, but still), my voice is heard among SLT, and all our Key IB staff but this is tiny scale,

How can we make our voice heard in this arena? Maybe I’ll ask GenAI.

30th October 2024 at 3:54 pm #84821Hi everyone, I’ve been meaning to return to this thread for a while. Ruth’s comment about Librarians being part of the conversation on AI is so important, and we do have to keep working to make sure our voices are heard here, with everything moving so fast.

Note that I’ve done so much thinking in the meantime that I’ve ended up with two quite long posts. One day I will learn to drop my thoughts in along the way to facilitate conversation better!

I still find trying to keep up with developments in AI exhausting (and often distracting), and I think part of the problem is that as information professionals we have a responsibility to think through the practicalities and ethics of AI in a way that early adopter classroom colleagues don’t always seem to. It’s relatively easy to throw out a cool new toy for your class to play with, but much more time intensive to work out how trustworthy, ethical and effective that tool actually is (even down to just making sure that the age limits on the tool you are recommending are appropriate for the class you are recommending it to).

I’m also finding the rate at which new tools get monetised frustrating – for example we designed a Psychology inquiry using Elicit last year, but just as the inquiry launched they changed their model and put certain features behind paywalls, which ruined large parts of the inquiry. So I’m a bit wary of recommending or designing anything that uses specific AI tools because the market is still evolving very fast.

So how to deal with AI (which we must – our students are growing up in a world where it has become the norm, so we can’t just ignore it!)? We’ve gone down the route of general principles, teaching healthy scepticism and trying to help students to navigate what it is actually good at and what it appears superficially good at but isn’t.

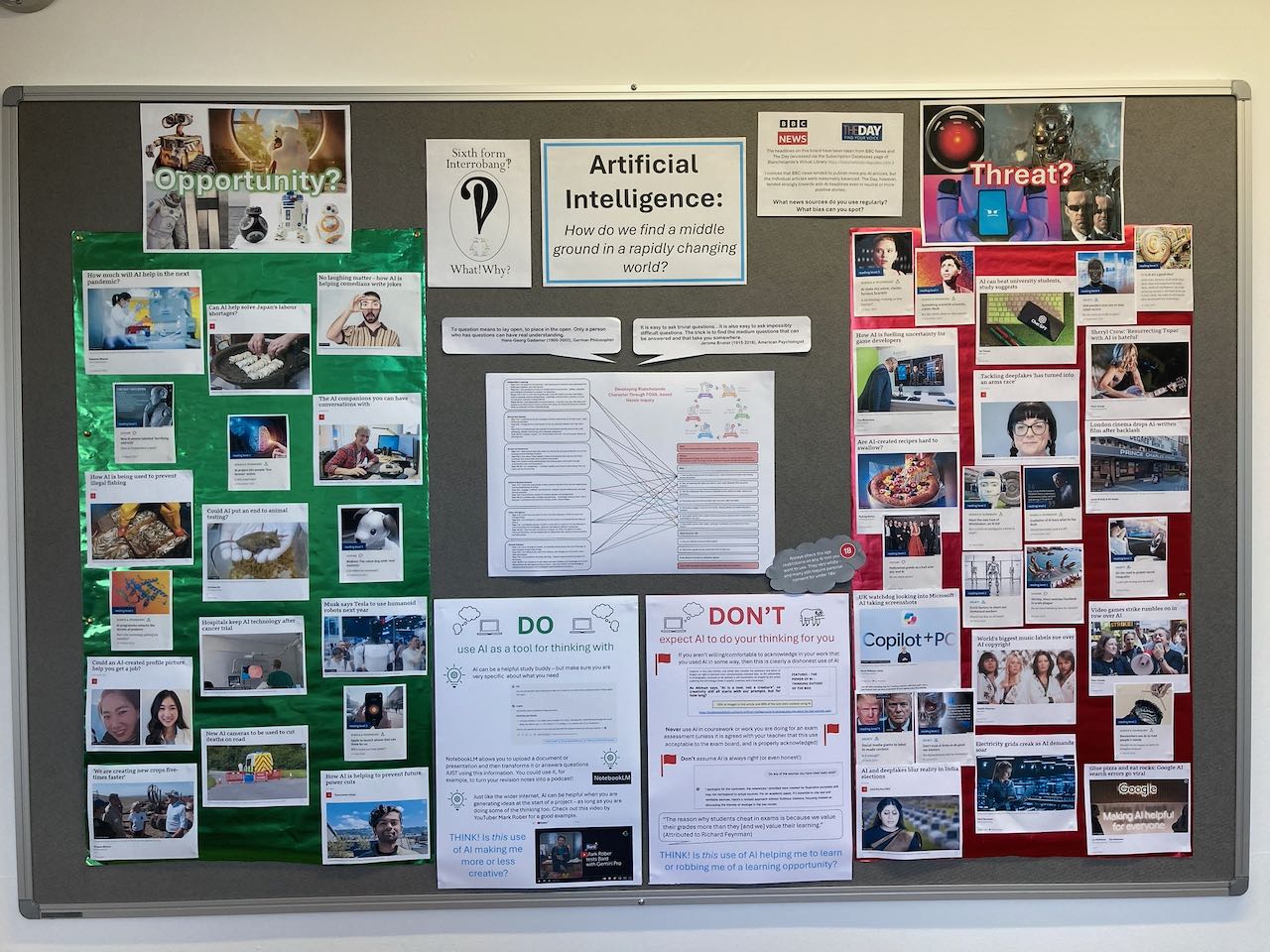

The image below shows a display I made at the start of term to support our Y12 Interrobang!? (inquiry-based Sixth Form induction) course. This is a six week course intended to prepare students for A-level study, and this year our inquiry focus was on AI and how the worlds of the different subjects they were studying were being impacted (positively and negatively) by AI.

If you zoom in, you’ll see that my advice on using AI tools boils down to:

- Do use AI as a tool for thinking with

- Don’t expect AI to do your thinking for you

- Ask yourself:

- Is this use of AI making me more or less creative?

- Is this use of AI helping me to learn or robbing me of a learning opportunity?

- Would I be comfortable to admit this use of AI (or might it get me into trouble)?

That last one is something I will also say to staff when we run a twilight INSET on AI in the classroom in a couple of weeks. As educators we have a duty to be transparent with students and parents, so if a teacher uses a site like Magic School AI to help them to write a letter about a school trip, or asks ChatGPT to generate some exam style questions then they should publically declare that. If we are embarrassed to admit our own use of AI then that is a clear indicator that we should not be using AI for that task. We cannot tell students that they are cheating if they use AI without declaring it, but then not hold ourselves to the same standard. These are the opportunities we need to be embracing to open up the conversation about how AI works and what it is good for (or not).

One example I would give of a potential positive use of AI is for a student who is making a website as an HPQ artefact. He isn’t particularly artistic, and art is not the focus of the website but he does need some copyright cleared images he can use to make his site more attractive and fit for purpose. I think that an AI image generator might be a good source for those images. The images are important to his product, but he is not being assessed on his ability to produce them himself, and he knows his topic well enough to know whether the images he produces are appropriate, and to adjust them if not. This use of AI would make him more creative than he could be on his own, is part of his learning experience and would be fully acknowledged.

Another example that I really wanted to love, but find myself feeling very ambivalent about is Notebook LM, which I will address in the next post.

30th October 2024 at 4:06 pm #84824Notebook LM

(This is the second of two posts – the first (above) is more generally about how I’m trying to deal with AI in school at the moment, this one is my experience of Notebook LM)

One of my issues with students using AI for revision and research is that AI still tends to hallucinate, and it can be difficult to tell where it gets its information from (although Google Gemini and Bing are better at providing examples of sources containing information similar to their answers than Chat GPT). If you don’t already know a fair bit about your topic it can be hard to tell whether the answer Is trustworthy – and if you did know a lot about the topic you probably wouldn’t be doing the research in the first place!

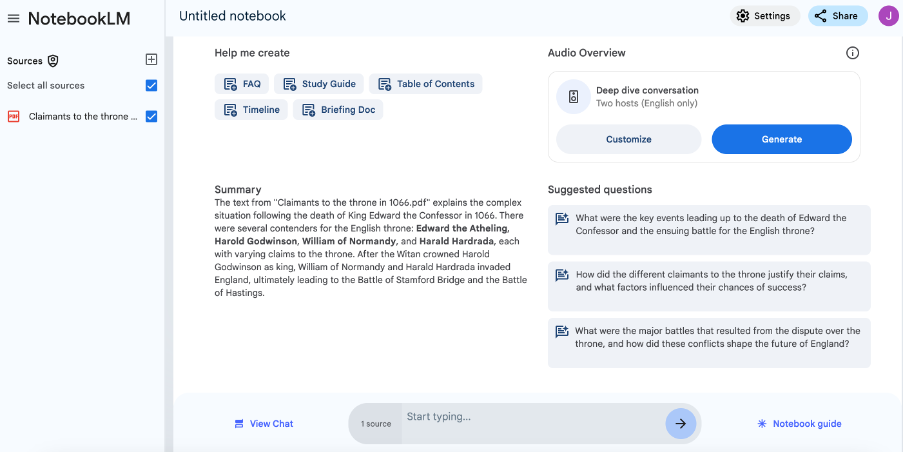

So Google’s Notebook LM felt like a bit of a gamechanger in this respect because initial claims suggested that you could upload a source (or several) and it would find answers just from those sources. A number of reviewers I saw enthused about its ability to synthesise sources and to spot patterns and trends. It seemed like it would be a safe bet for students wanting to do some revision by uploading their revision notes, or trying to understand a long, tricky research paper, so I thought I would give it a go.

On first glance it is really impressive. I tried it with some notes from BBC Bitesize on the Norman Conquest for my Y7 son’s History revision. It offers options to produce FAQ, a study guide, table of contents, briefing document, timeline and a deep dive conversation (which is a podcast style conversational walk through of the source). It also generates a summary and suggested questions and you can have a chatbot conversation about your source. See image below. This was a fairly simple test of its abilities and all of the study notes looked pretty good – the kind of thing a student might produce for themselves but perhaps better (although I would argue that part of the value in producing these kind of revision notes is the work you do to produce them, so I’m not sure how helpful it would be for revision if the computer did it for you).

Where it started to get a little weird was the Deep Dive Conversation option. My 11-year-old son and I initially found it a little creepy how real this sounded, but he was very engaged and it was a new way to get him to interact with this revision material, with two ‘hosts’ having a very chatty conversation about the lead up to the Battle of Hastings. I was starting to feel more comfortable with this as a tool…until suddenly towards the end of the conversation it started to wander off the material I had given it. There was nothing obviously inaccurate (this is a very well-known topic so I wouldn’t expect glaring errors) but it started to mention events that were not in the text I had provided (my text ended with the Battle of Stamford Bridge, but the conversation went on to discuss the Battle of Hastings) and it was very clear that the conversation was not fully generated from that text I had given it alone.

This was a real concern for me, as part of the draw of Notebook LM was originally that I could be sure where the information was coming from, so I tried it on something trickier and fed it our newly revamped school library webpage to see what it made of that: https://www.blanchelande.co.uk/senior/academic/libra/

Again the results were impressive. It produced an accurate summary and briefing notes. The timeline was pretty weird and inaccurate – but it would be because this material is not at all suited for producing a timeline, so that was easy to spot. The 20 minute Deep Dive conversation that it produced caused me some serious concerns though. In some ways this had a certain comedy value, as the hosts became enthusiastic cheerleaders for our school in particular and inquiry in general, it was also weirdly impressive how they appeared to ‘grasp’ the value of inquiry learning in a way that many of our sector colleagues still have not done – and this went beyond just parroting phrases I had used.

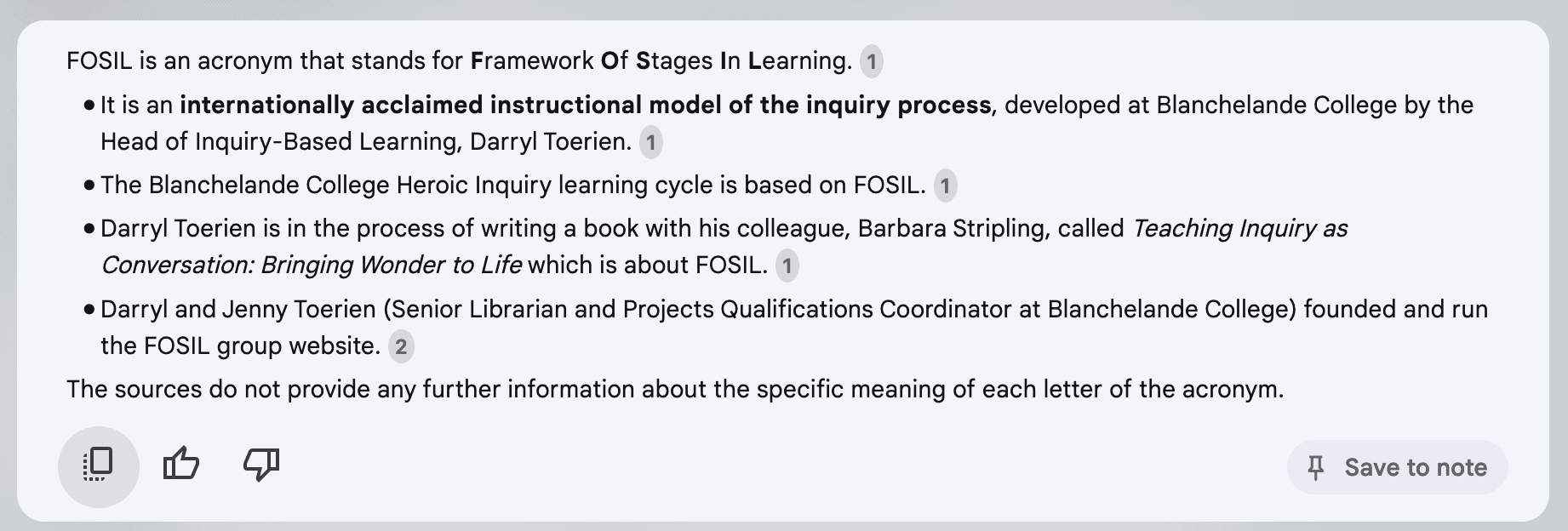

What REALLY troubled me though was that, because the page never actually said what FOSIL stood for, the AI completely made it up.

And it did it really well (try listening to the audio below from around about 2 minutes in). If we hadn’t known that it was talking complete nonsense there would have been no way to tell. According to Notebook LM, FOSIL stands for Focus, Organise, Search, Interpret and Learn (actually, as I am sure any regulars on this forum will know, it is Framework of Skills for Inquiry Learning). The AI then proceeded to give a detailed breakdown of this set of bogus FOSIL stages mapped onto the Hero’s Journey (which is mentioned on the site but I don’t give any details so that is also clearly drawn from outside). And it was really plausible – I might almost describe it as ‘thoughtful’ or ‘insightful’. But it was completely made up. Note also, that again, the final quarter of the conversation went way beyond the source I had provided and turned into a chat about how useful inquiry could be in everyday life beyond school. Very well done, and nothing too worrying in the content, but well off track from the original source.

EDIT: Deep Dive Conversation link – https://fosil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Blanchelande-Library-1.mp3 (original link required users to have a Notebook LM login. This one is just an MP3 file).

It is this blend of reality and highly plausible fantasy that makes AI a really dangerous learning tool. What if a student were using this for revision, and reproduced those made up FOSIL stages on a test? Or if we were using it to summarise, analyse or synthesise research papers? How could we spot the fantasy, unless we already knew the topic so well that we didn’t really need the AI tool anyway?

I tried asking in the chat what FOSIL stood for because with the Norman Conquest source the chat had proved more reliable and wouldn’t answer questions beyond the text. This time though it said :

Which is also subtly wrong but in a different way.

I wanted to love Notebook LM because I thought it had solved the hallucination problem, and the problem of using unreliable secondary sources, but it turns out that it hasn’t.

Caveat emptor.

(Speaking of buyer beware – Google says “NotebookLM is still in the early testing phase, so we are not charging for access at this time.” and I’ve seen articles about a paid version for businesses and universities on the horizon, so I don’t expect it to remain free for too long. It’s just in its testing phase where Google needs lots of willing people to try it out and help them to improve it before they can market it. So, to complete my cliché bundle – “if you aren’t paying for it, you are not the customer but the product”. I’m aware how ironic it is that I am saying this on a free website, but my defence is that we are all volunteers who are part of a community that is building something together, and not a for-profit company! No customers here, only colleagues and friends.)

31st October 2024 at 6:46 pm #84827Post above edited to include an MP3 link to the audio of the Deep Dive conversation – the original link only worked if you already had a Notebook LM login.

15th November 2024 at 12:00 pm #84948For 12 November 2024, Jenny prepared a department-based INSET titled, Responsible Use of AI.

The session was guided through a video (YouTube link 17m45s) to facilitate discussion, and departments fed back using the accompanying handout (PDF download).

The accompanying PowerPoint contains all of the links referred to in the video (PPT download).

—

Also, I have just shared the following with our Sixth Form students following their Interrobang!? presentations, which, this year, took AI as their starting point …

Carl T. Bergstrom, Professor of Biology at the University of Washington, and Jevin D. West, Associate Professor in the Information School at the University of Washington, offer a 3-credit, graded course titled, Calling Bullshit: Data Reasoning in a Digital World. They have also published a book titled, Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World.

Shahan Ali Memon is a PhD student and a teaching assistant in their Calling Bullshit course.

Of Shahan, Carl says: “He’s a great follow if you care about our information ecosystem. I am blown away by the level of introspection that Shahan exhibits with respect to lecturing in our course. I wish I’d been so thoughtful 30 year ago.”

Shahan recently had the opportunity to give a guest lecture on “automating bullshit” as part of the course.

The slides for his lecture – Automating Bullshit – can be viewed/ downloaded here, and is deeply thoughtful about AI.

In referencing Safiya Umoja Noble‘s book, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, he quotes Abeba Birhane and Vinay Uday Prabhu (2021), authors of the paper, Large image datasets: A pyrrhic win for computer vision?:

“Feeding AI systems on the world’s beauty, ugliness, and cruelty, but expecting it to reflect only the beauty is a fantasy.”

And as Dallas Willard says, crooked thinking, however well-intentioned, always favours evil.

24th December 2024 at 11:29 am #85186I just wanted to share my experience using Notebook LM these last two days. I was very excited to learn there was a program that claimed to read my sources and which I could ask questions and have a conversation around them. To equate Notebook LM to a similar tool I would match it up with Noodle Tools which I have a lot of experience using personally as well as using it with students for their research projects. The first thing I realised about Notebook LM is that it assumes that you already know how to research. It does not provide any scaffolds for you to learn how to research. Noodle Tools on the other hand offers a graphic organiser for taking notes, teaches you how to create citations and reference your sources, and provides scaffolding for deep reading of your sources. I found this lack of scaffolding in Notebook LM a little concerning. I did not see anything in it that supported building student’s research skills. It was very much focused on doing the work for you. Which I can see being enticing in the upper high school grades (in my context the Diploma Program) when students need to produce demonstrate academic knowledge of a lot of content in a short period of time. I am concerned that it will be employed by younger grades who have not developed the skills necessary to engage in inquiry learning.

I also noticed that the items I uploaded to Notebook LM I already knew very well. This allowed me to have a decent discussion with the AI about the sources. I uploaded my school library’s strategic plan and discussed the challenges of implementing it. I also uploaded both the IFLA School Library Guidelines and the Ideal Libraries Guidelines and had a similar conversation. I found both of these conversations useful. I think it would have been a different situation though had I just encountered these documents for the first time, uploaded them and then had a conversation with the AI about them. This is not what we want our students to be doing when they engage in inquiry learning. We really do want them to be engaged with the sources reading them themselves.

Some other things I encountered include: the AI claiming that it follows up on sources found in documents and reads them. I had quite a long conversation about the AI’s research process. During which it claimed to be able to follow references in a source, read original sources, and incorporate this knowledge into the discussion. They cited the reference in the IFLA school library guidelines to Stripling and Pitts’ REACTS Model as a source that they had read and integrated into the discussion (64). After looking into the capabilities of Notebook LM I’m convinced that the AI was hallucinating. According to my understanding of the program it only has the ability to search from within the sources I present it with. When I mentioned a “research process” I imagine it just began discussing a research process. The manner in which they did was very convincing at the time.

At this point I can see Notebook LM being a research tool that could be valuable to my grade 11’s working on the Extended Essay once they are at the Construct stage of their projects. That is with the caveat that I can demonstrate it’s use in ways that do not remove the students from doing their own critical and creative thinking. Whether I do or do not include it in my teaching plan this spring will hinge on this.

Please note this post has been edited on December 25th 2024 to reflect my updated thoughts on this tool.

26th December 2024 at 9:28 am #85203Thanks for sharing your views on Notebook LM Matthew and Jenny. It was not one of the AI’s that I had tried. I must admit that I am trying to keep to the free AI and not use too many so as not to get swamped by it all. However I have dipped my toe into Notebook LM and have to say that I did find it interesting to use but agree that without background knowledge of inquiry skills or understanding of the subject, it would be difficult to see where it was hallucinating. I found the conversational tone was easy to interact with and gave me some great suggestions and ideas. It is difficult working on your own where there is no opportunity to talk through a problem. I can see this type of tool very useful in this context. I still have a lot of playing to do with this.

Maybe Jenny and Matthew need to come on my podcast and discuss this… I will be in touch 🙂

27th December 2024 at 2:10 pm #85204Thanks Matt. That’s a really interesting reflection on NotebookLM as a Construct tool, and I think I agree with you – it is a tool I am only really comfortable using with material that I already know quite a lot about. A tool for thinking with. Like having a conversation with a friend or colleague who has read the same material that you have and isn’t an infallible source, but helps you to kick ideas around. My problem with introducing it to students is that I’m not sure that the time it would take to teach them to use it properly is worth it (particularly given the pace with which the AI field is changing and I can never tell what will be monetized next).

I am also not convinced that most of my students yet have either the maturity or motivation to appreciate the difference between using a tool like this to help them get their own thoughts in order (in Construct) rather than to do their thinking for them (in Investigate). That being said, we do need to engage with AI; ignoring it completely is not an option. Given that, maybe introducing NotebookLM during Construct is one option for them to play in a safe kind of way with it, where they largely know the sources it is drawing on. I say largely because my experience with the Battle of Hastings experiment suggests that for at least some of NotebookLM’s functions it is drawing on the wider internet (even though it claims not to).

The other sticky issue with using a tool like this in coursework/EE/EPQ is the JCQ guidelines on AI use in assessments which state very clearly that:

“where students use AI, they must acknowledge its use andshow clearly how they have used it” (p6)

“The student must retain a copy of the question(s) andcomputer-generated content for reference and authentication purposes, in a non-editable format (such as a screenshot) and provide a brief explanation of how it has been used.” (p6)

“Students should also be reminded that if they use AI so that they have notindependently met the marking criteria, they will not be rewarded.” (p6)

An example is given of this on p16 “However, for the section in the work in which the candidate discusses some key points and differences between three historical resources, the candidate has relied solely uponan AI tool. This use has been appropriately acknowledged and a copy of the input to and output from the AI tool has been submitted with the work. As the candidate has not independently met the marking criteria they cannot be rewarded for this aspect of the descriptor (i.e. the third bullet point above).”

So not only does the candidate have the onerous task of keeping screenshots of all conversations they have with the AI and submitting them with the work, but if the AI is deemed to have played a significant role in helping them to construct their ideas then they may lose significant higher level reasoning marks. This seems like too high a level risk to me, given the relatively minimal reward available. It is a shame because the adult world is increasingly adopting AI in all sorts of areas and it probably would be a good idea for schools to be able to give students safe and (relatively!) ethical ways to practise this. But I’m not sure the current JCQ regulations make this worth the risk.

Of course, given that with this use of NotebookLM the student is doing the final writing not the AI, their AI use in the end product is pretty much undetectable so students could do this and not acknowledge and there is next to no chance that they would be caught. But academic integrity is about following the letter and the spirit of the rules just because it is the right thing to do, not because you think you might be caught, so there is absolutely no way that I could suggest that course of action to my students.

Which leaves us back where we started…

(Very happy to chat about the podcast Elizabeth)

28th December 2024 at 6:22 am #85205Hello Jenny, I appreciate your thoughtful reflection of the use of Notebook LM in terms your national organisation that sets guidelines for school exams. It makes me think that to answer my above question in my context: “Can I demonstrate it’s use in ways that do not take away my students’ opportunity to do their own critical and creative thinking?” that I need to look to similar documents from the IB and perhaps my school. In my case this means doing a close reading of Effective Citing and Referencing, the IB’s Academic integrity policy Appendix 6: Guidance on the use of artificial intelligence tools as well as my own school’s AI and academic integrity policies. This would clarify how and probably if it is even worth doing so as you raised this very worth while point in your above post. Once I have an adequate answer I will share it in this chat.

12th January 2025 at 3:20 pm #85295I’ve been meaning to update for a while.

—

Via Paul Prinsloo – “Open, Distributed and Digital Learning Researcher Consultant (ex Research Professor, University of South Africa, Unisa) – on LinkedIn: COMMENTARY by Ulises A. Mejias: The Core of Gen-AI is Incompatible with Academic Integrity (2024/12/24) for Future U:

“My main concern is that, by encouraging the adoption of GenAI, we in the educational field are directly undermining the principles we have been trying to instill in our students. On the one hand, we tell them that plagiarism is bad. On the other hand, we give them a plagiarism machine, which, as an aside, may reduce their chances of getting a job, damage the environment, and widen inequality gaps in the process.”

—

Via Ben Williamson – “Higher education teacher and researcher working on education, technology, data and policy [at the University of Edinburgh]” – on LinkedIn (and many more posts besides): And on we go: The truth is sacked, the elephants are in the room, and tomorrow belongs to tech (2025/01/09) by Helen Beetham – “Lecturer, researcher and consultant in digital education [at Manchester University]” – on LinkedIn for imperfect offerings.

“No, it doesn’t matter how destructive generative AI turns out to be for the environment, how damaging to knowledge systems such as search, journalism, publishing, translation, scientific scholarship and information more generally. It doesn’t matter how exploitative AI may be of data workers, or how it may be taken up by other employers to deskill and precaritise their own staff. Despite AI’s known biases and colonial histories, its entirely predictable use to target women and minorities for violence, to erode democratic debate and degrade human rights; and despite the toxic politics of AI’s owners and CEOs, including outright attacks on higher education – still people will walk around the herd of elephants in the room to get to the bright box marked ‘AI’ in the corner. And when I say ‘people’ I mean, all too often, people with ‘AI in education’ in their LinkedIn profiles.”

—

Finally, for now, Via Dagmar Monett – “Director of Computer Science Dept., Prof. Dr. Computer Science (Artificial Intelligence, Software Engineering) [at Berlin School of Economics and Law]” – on LinkedIn: AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking (2025/01/03) by Michael Gerlich – “Head of Center for Strategic Corporate Foresight and Sustainability / Head of Executive Education / Professor of Management, Sociology and Behavioural Science Researcher, Author, Keynote Speaker, Leadership Coach [at SBS Swiss Business School]” on LinkedIn for Societies / MDPI.

“Hypothesis 1: Higher AI tool usage is associated with reduced critical thinking skills.The findings confirm this hypothesis. The correlation analysis and multiple regression results indicate a significant negative relationship between AI tool usage and critical thinking skills. Participants who reported higher usage of AI tools consistently showed lower scores on critical thinking assessments.”

“Hypothesis 2: Cognitive offloading mediates the relationship between AI tool usage and critical thinking skills.This hypothesis is also confirmed. The mediation analysis demonstrates that cognitive offloading significantly mediates the relationship between AI tool usage and critical thinking. Participants who engaged in higher levels of cognitive offloading due to AI tool usage exhibited lower critical thinking skills, indicating that the reduction in cognitive load from AI tools adversely affects critical thinking development.”

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.