Jenny Toerien

Active 2 days, 16 hours agoRole: Librarian and EPQ/HPQ Co-ordinator

Town/City: Guernsey

Country: United Kingdom

Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

14th February 2026 at 4:02 pm in reply to: FOSIL in a Standalone Middle School Media Skills Course #89309

Hi Matthew. Thank you for sharing your work on this – and congratulations for managing to achieve your goal of integrating your media skills into cotaught units. We’ll all be really interested to hear how that goes, which subjects you are collaborating with and what you find works better and what less well when coteaching. We’ve generally tended towards integrating inquiry into classroom subjects where possible because we have found that it is easier for students to see the importance and relevance of what they are doing when it is embedded in another subject* – and it is a good opportunity to help colleagues to integrate inquiry into their own practice, even beyond the collaboration. However it does come with its own challenges (such as shared ownership of classes and needing to negotiate time, learning objectives and assessment). Once you get going we would love to hear how your experience of shifting work that you have developed in a stand alone course into co-taught units, and perhaps how the opportunity to develop some of the lessons and ideas in your standalone course first feeds into your collaboration.

(*the main exception for me being EPQ and HPQ, where inquiry IS the subject in its own right, but is leant direction and purpose by the qualification at the end).

16th February 2025 at 2:06 pm in reply to: Session 3a: Ruth Maloney (Tonbridge Grammar School) #85594Hi Ruth,

I’m with you both here – let’s get FOSIL in there and THEN get them to reverse the order. Just think if over time you could persuade them to call this skillset “Inquiry Skills” and give FOSIL as an example of “An organised process for conducting an inquiry”… While they are using fuzzy language here, we are all on a journey and have to start where we find ourselves. After all, the first iteration of FOSIL (many years ago) was “Framework for Oakham School Information Literacy“. We have come a very long way in our understanding of inquiry since then, arriving at the Framework Of Skills for Inquiry Learning, but if Darryl hadn’t started out looking for an information literacy model we would never have arrived at an inquiry model. The IB are interested in the research process, so work with them to show them that inquiry gives them the model they need and so much more besides.

On a separate note, I’ve been thinking since last week about your excellent Sixth Form inquiry focussing on Investigate that tried to slow them down and stop them jumping to conclusions. You said that they struggled with the idea of no concrete Express phase and I wondered if you could give them an Express that didn’t focus on conclusions. How about imagining they are a reference librarian or perhaps a parliamentary researcher, and their job isn’t to find an answer to the question (or even necessarily to find the question) but to collect a balanced set of reputable resources that address their topic from a range of angles to allow the client to draw their own conclusions? This way they have a concrete product that explicitly precludes drawing conclusions. They could produce a briefing paper/leaflet/poster for their client that summarises the main areas of argument and gives resources for further study for each. (Briefing paper might be the wrong phrase here as those usually propose solutions I think, and we don’t want them to do that. I’m not sure what the correct phrase would be).

What you are doing sounds like such an excellent idea, I think you were saying that it just needs some focus for the students so they know what they are aiming for at the end.

11th February 2025 at 1:08 am in reply to: Programme, contents list and video playlist for the 2025 FOSIL Symposium #85491Links to forum topics with discussion, presentations and videos:

- General discussion of the event

- Session 1a: Welcome | Elizabeth Hutchinson (with additional written remarks by Darryl Toerien)

- Session 1b: Revolutionary musing | Dianne Oberg

- Session 1c: The revolution will not be televised | Lee FitzGerald and Joanne Bleby

- Session 2a: FOSIL Developments Part 1: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (IAI)

- Founding the Institute | Darryl Toerien

- Symbolising the Institute | Lara Stanford

- Integrating the Institute | Jane Grange

- Hosting the Institute | Alexa Yeoman

- Valuing the Institute | Mark Le Page

- Session 2b: FOSIL Developments Part2:

- Conceptualising Heroic Inquiry | Darryl Toerien

- Reconceptualising Heroic Inquiry | Hugh Rose, Illustrator of Traditional Stories

- Session 2c: Revolutionary musing | Mary-Rose Grieve

- Session 3a: The revolution will not be televised | Ruth Maloney

- Session 3b: The revolution will not be televised | Jannath Khanom

- Session 4a: The revolution will not be televised | David Harrow, Faye Marland, and Nick O’Loughlin

- Session 4b: Concluding revolutionary musing | Barbara Stripling

- Session 4c: Farewell | Elizabeth Hutchinson

10th February 2025 at 10:23 pm in reply to: Programme, contents list and video playlist for the 2025 FOSIL Symposium #85490

—

Full video playlist is below. Links to the presentations and opportunities to comment are in the relevant topics in this forum:

27th January 2025 at 9:28 pm in reply to: Year 6 (Grade 5) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #85330P.S. I did ask Dorling Kindersley whether we could share the version of the English booklet (Central Inquiry Journal) with the single double page spread from their book Dorling Kindersley (2018) How Science Works. p.118-9 and unfortunately they said no because it would be freely available to anyone, rather than behind a paywall. Even though is is just two pages of a seven year old book.

Anna Claybourne (author of Claybourne, A. (2013) My First Book of Science. P.44-5) said she would happily give permission to use her work if she held the copyright, but she thought we would need the publisher’s permission too. Unfortunately the original publisher no longer exists and I can’t work out who they might have sold the rights to…

So the upshot is that I have had to remove the comprehension texts from the forum uploads and just leave the questions. If you want to reconstruct a similar journal you would need to use texts that your school owns, which can then be copied under fair use copyright.

27th January 2025 at 9:11 pm in reply to: Year 6 (Grade 5) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #85325I will post more as we move through the inquiry, but as we enter the fourth year of the Y6 Signature Work I can really see the benefits of running and refining an inquiry over a number of years. Key developments this year:

- I’ve set up a Team to manage all our communications (and saved copies of all the files into the associated SharePoint). With ten members of staff involved across about six months, this has helped to keep everyone in step.

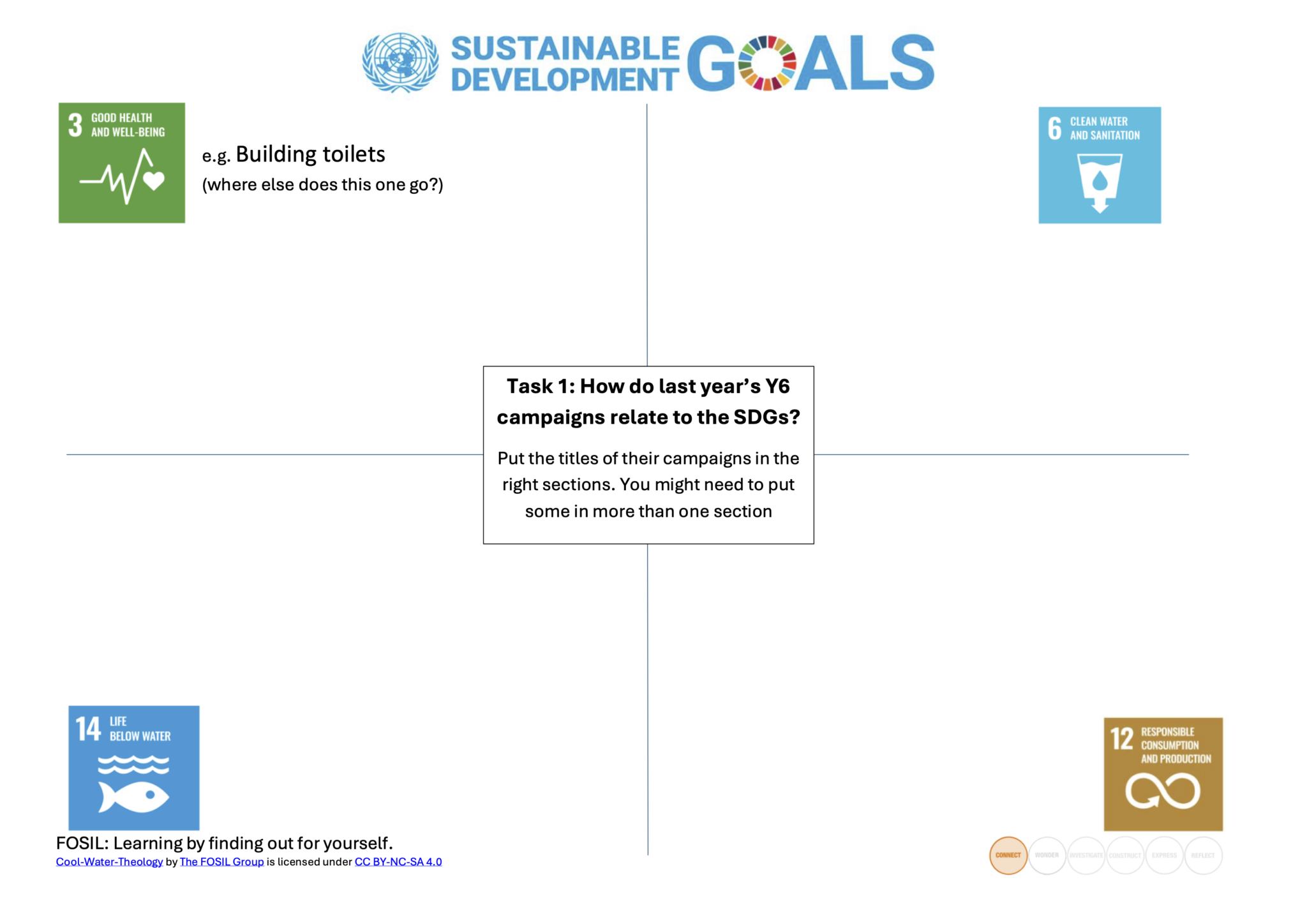

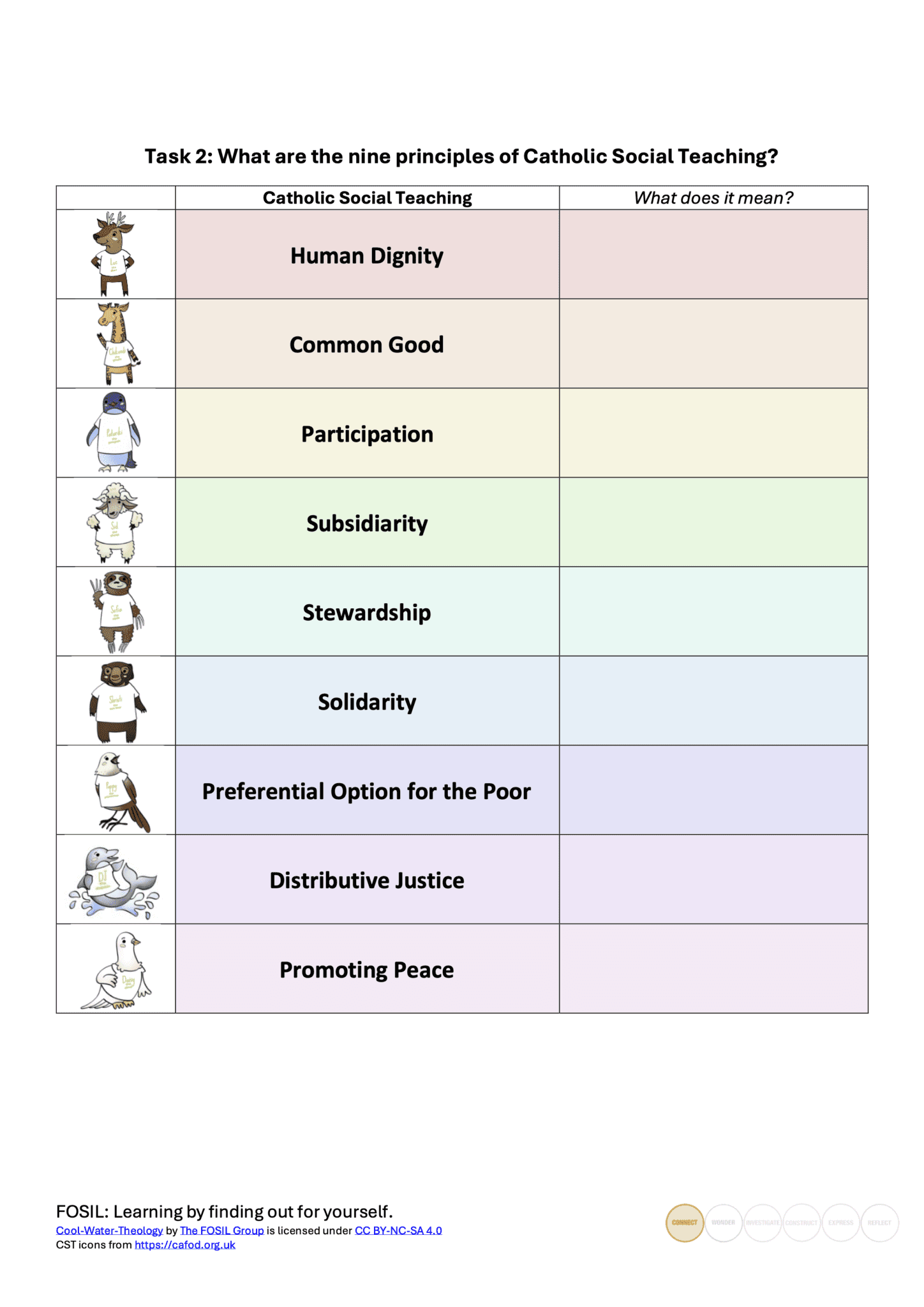

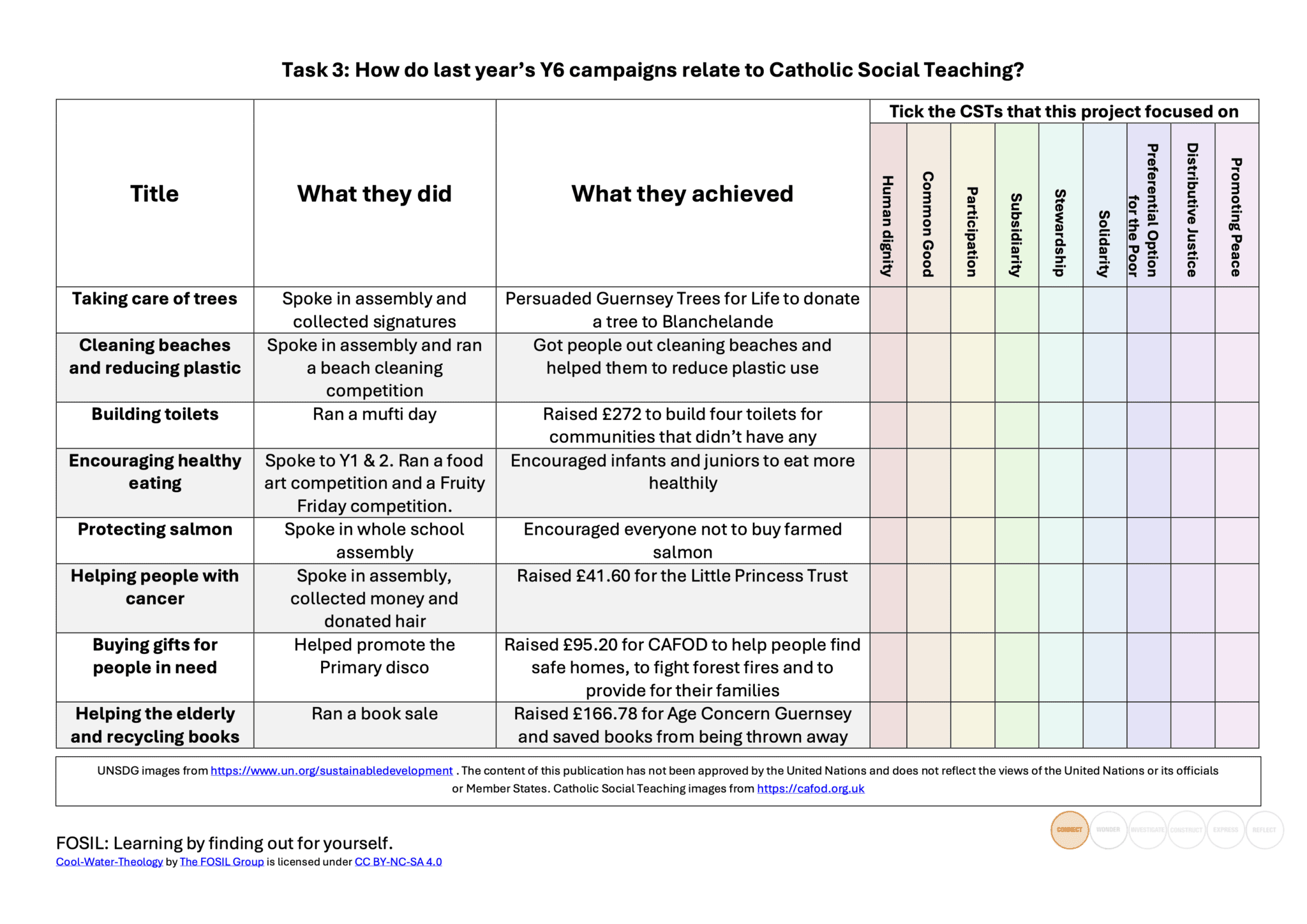

- We added an introductory Theology lesson (we are a Catholic School and our Y6 do Catholic Social Teaching in the Christmas term, which fits in perfectly with the campaigns). We looked at how last year’s campaigns fitted in with Catholic Social Teaching and my plan is to incorporate some of this into this year’s campaign planning. You could do a similar thing with citizenship, or with a different Religious Studies curriculum. I have also mentioned it to the Geography teacher who is going to mention Responsible Production and Consumption as part of her unit on Everest.

- I am in the process of inviting local charities in to a marketplace event to help Y6 choose which causes thye want to support after half term. I am really excited about this development, which is a natural extension of some of the connections last year’s groups made with some local charities.

There have also been a couple of key changes to the structure. I was asked to move the spine of the inquiry to ICT rather than English because of pressure on the English curriculum time, but with some additional lessons in English at important points when English skills are the focus. When we were in the process of developing the project I taught all of the spine lessons (in part because I hadn’t yet developed it fully enough to confidently explain to someone else where it was going), but this year I have been able to hand control of certain parts of the spine over to one of the English teachers who is also the ICT teacher. We still team teach these lessons, but he takes the lead now.

It is such a priviledge to work with talented colleagues like this, and handing these lessons over has reminded me how important the subject specialist is in inquiry. As a Y6 English specialist, he has done a much better job that I did of teaching the skills of understanding and interrogating a non-fiction text at the right level for this age-group, and I think this year’s group understand the Science they have learnt from these texts better than last year’s (even though I am a Science specialist). Although we have continued to use all the materials I developed over the last few years, his understanding of their reading ability and what kind of scaffolding they need to access these kind of texts has really brought this part of the unit to life.

As the Science teachers are more used to the unit I have also felt able to let go a bit there (which has helped as one group’s Science lessons are timetabled at the same time as the other’s ICT lessons and I can’t be in both places at once!), although I did cover one of these lessons last week when the teacher couldn’t be there and I pop in when I can to lemd a hand.

The water bottle covers are evolving in Art (they are using some screen printing techiques this year), and I’m looking forward to dropping in to help out a bit with needle threading for some of the sewing lessons this week.

Although I do still co-ordinate the inquiry and play an important part in helping it to run smoothly, every year it is more of a community effort – which means the students benefit from a wide range of expertise, and as staff get more comfortable with it, inquiry ideas and practices are more likely to seep out into their other teaching. It also means that, although I am still an important part of the inquiry team, it does not absorb all my attention in quite the same way as it did in previous years, leaving me time to work with other teachers on other inquiries (e.g. Y8 Theology, Y4&5 Geography).

This intense focus on flagship inquiries (involving communities of colleagues) which, once set up and running, require decreasing amounts of attention from me every year, allowing me to turn my attention to new projects, possibly with different colleagues, feels like a sustainable model for inquiry growth within our school.

Thanks Matt. That’s a really interesting reflection on NotebookLM as a Construct tool, and I think I agree with you – it is a tool I am only really comfortable using with material that I already know quite a lot about. A tool for thinking with. Like having a conversation with a friend or colleague who has read the same material that you have and isn’t an infallible source, but helps you to kick ideas around. My problem with introducing it to students is that I’m not sure that the time it would take to teach them to use it properly is worth it (particularly given the pace with which the AI field is changing and I can never tell what will be monetized next).

I am also not convinced that most of my students yet have either the maturity or motivation to appreciate the difference between using a tool like this to help them get their own thoughts in order (in Construct) rather than to do their thinking for them (in Investigate). That being said, we do need to engage with AI; ignoring it completely is not an option. Given that, maybe introducing NotebookLM during Construct is one option for them to play in a safe kind of way with it, where they largely know the sources it is drawing on. I say largely because my experience with the Battle of Hastings experiment suggests that for at least some of NotebookLM’s functions it is drawing on the wider internet (even though it claims not to).

The other sticky issue with using a tool like this in coursework/EE/EPQ is the JCQ guidelines on AI use in assessments which state very clearly that:

“where students use AI, they must acknowledge its use andshow clearly how they have used it” (p6)

“The student must retain a copy of the question(s) andcomputer-generated content for reference and authentication purposes, in a non-editable format (such as a screenshot) and provide a brief explanation of how it has been used.” (p6)

“Students should also be reminded that if they use AI so that they have notindependently met the marking criteria, they will not be rewarded.” (p6)

An example is given of this on p16 “However, for the section in the work in which the candidate discusses some key points and differences between three historical resources, the candidate has relied solely uponan AI tool. This use has been appropriately acknowledged and a copy of the input to and output from the AI tool has been submitted with the work. As the candidate has not independently met the marking criteria they cannot be rewarded for this aspect of the descriptor (i.e. the third bullet point above).”

So not only does the candidate have the onerous task of keeping screenshots of all conversations they have with the AI and submitting them with the work, but if the AI is deemed to have played a significant role in helping them to construct their ideas then they may lose significant higher level reasoning marks. This seems like too high a level risk to me, given the relatively minimal reward available. It is a shame because the adult world is increasingly adopting AI in all sorts of areas and it probably would be a good idea for schools to be able to give students safe and (relatively!) ethical ways to practise this. But I’m not sure the current JCQ regulations make this worth the risk.

Of course, given that with this use of NotebookLM the student is doing the final writing not the AI, their AI use in the end product is pretty much undetectable so students could do this and not acknowledge and there is next to no chance that they would be caught. But academic integrity is about following the letter and the spirit of the rules just because it is the right thing to do, not because you think you might be caught, so there is absolutely no way that I could suggest that course of action to my students.

Which leaves us back where we started…

(Very happy to chat about the podcast Elizabeth)

2nd December 2024 at 8:25 pm in reply to: FOSIL and the IB Diploma Programme Extended Essay (EE) #85069JCS are planning a revision of my 15 January 2021 article The role of the librarian in the IBDP and have kindly allowed me to preserve the original below. Bear in mind that this is a historical post. I am no longer in an IB school – my Level 3 focus now is the Extended Project Qualification and our support for that is very different. However, I think some of the lessons we learnt along the way are still valid and worth reflecting on.

“The role of the librarian in the IBDP

This guest post is by Jennifer Toerien. Jennifer is Curriculum Librarian for Upper School at Oakham School, where students have the option to study in International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IBDP). It was originally published on the Investigating Knowledge blog [no longer running] on 02 December 2020 and has been republished with permission.

If you are reading this you are probably in an International Baccalaureate (IB) school – which means you are very lucky because you almost certainly have a school librarian to support you. But what is the unique role that a librarian should have in your education, and how can you make the most of what your librarian is offering?

It’s not all about the books!

School libraries around the world are under threat (BBC, 2017; ABC news, 2017; Citylab, 2019). As school budgets are being squeezed, many regard a professional librarian (and often even a library) as a luxury they can’t afford rather than an educational necessity. The problem is largely one of definition, and of understanding (both among school leaders and librarians themselves) of what a school librarian does. And that is why the situation is often different in IB schools. The traditional definition of a librarian is “a person in charge of or assisting in a library” (1), where a library is “a building or room containing collections of books, periodicals, and sometimes films and recorded music for use or borrowing by the public or the members of an institution” (2).

In a world where so much information is freely available online, ebooks are on the rise and many print books are cheap to buy, some have even suggested that libraries should be replaced by a well-known online retail giant (Guardian, 2018). But regardless of the arguments about the importance of books in education (and I am convinced they are still very important), the real problem often lies in school librarians grounding their identity in books and reading, not in education. The central purpose of schools is education and that should be the central purpose of school librarians too. If “they aren’t buying what we’re selling” then maybe the problem is with us, not them!

Fortunately, the IB recognises this and has published a document entitled Ideal libraries (IBO, 2018) explaining (3) what you should be able to expect from your school library. It defines (school) libraries as “combinations of people, places, collections and services that aid and extend learning and teaching.” (p.2). Notice that books aren’t mentioned at all – not because they aren’t an important and valuable part of our job, but because they are a tool we use to achieve our purpose, not the reason we exist. This astonishing and inspiring document goes on to explain the key roles of the librarian, and I am going to use it to explain what you should be expecting from your school librarian, and why they are a fundamental part of your IB education.

So what does a school librarian do?

The IBO says in Ideal Libraries that:

Library/ians act as curators of information, caretakers of content and people, catalysts of people and services, and connectors to sources of information, multiliteracies, and reading. Librarians’ responsibilities are inspired by the learning environments they engage with, and in that capacity, they are co-creators of information with the school and the wider community. They challenge learners to seek appropriate information, to use sound methods of inquiry and research, and teach them to question the information they find and use. (p.5)

In short, your librarian is the person to know if you want to learn how to access and work with information to generate and/or answer an inquiry question. You might expect your librarian to have the skills to locate and access information on whatever obscure topic you may have chosen for your EE (or IA), but our role goes far beyond that. It’s our job to be able to teach you to understand how to journey from the vague stirrings of an interest in a topic all the way through to a carefully researched, tightly argued and appropriately sourced and referenced essay answering a thoughtfully worded inquiry question within the space of about nine months, reflecting as you go. In short, it is our job to turn you into an academic researcher (although we prefer the term inquirer).

Shaping the IB Extended Essay process

Your teachers and supervisors are subject specialists, but your librarian is the specialist in inquiry. “Inquiry is an approach to learning whereby students find and use a variety of sources of information and ideas to increase their understanding of a problem, topic or issue. It requires more of them than simply answering questions or getting a right answer.” (Kuhlthau, 2007, p. 2). More broadly, “inquiry is a dynamic process of being open to wonder and puzzlement and coming to know and understand the world, [and] as such, it is a stance that pervades all aspects of life and is essential to the way in which knowledge is created” (Galileo Educational Network).

The Extended Essay may be your first major step into the type of inquiry where you have real freedom to choose your own topic, so it makes sense that it should be guided by someone who really understands the process. At Oakham School, our journey with inquiry began with an examination of the EE process and how it could be reshaped to support our students more effectively. In 2010 Darryl Toerien, the Head of Library, had been developing his understanding of inquiry through the work of Carol Kuhlthau and Barbara Stripling. He realised that the EE process that he had inherited when he joined the school in 2008 was largely driven by an administrative need to make sure that students met certain deadlines rather than by a deep understanding of the inquiry process and what it would take for them to get there.

[Image to add later: Oakham School’s first EE timetable (2001-3 cohort)]

Most glaringly, students were expected to select their research question within four weeks of their first introduction to the EE, but were then only given dedicated off-timetable time to work on the EE six months later, a week before their first draft was due. While they were expected to start gathering research materials much earlier, there was no real expectation of any substantial reading until EE “research week”, when they needed to do their reading and writing together in a fairly short concentrated space of time.

From his understanding of Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process, Darryl realised that the inquiry question only emerges from a deep understanding of the topic, achieved by using resources to investigate the topic and build understanding. You go into your investigation with an idea and a direction, and emerge with an understanding of an appropriate question to answer. He also realised that the most challenging, transformative and important work of the EE is not what is often called the “research” – finding resources and reading them – or even writing the essay. It is what comes in between those two – constructing a new (to you) understanding of your topic based on what you have read. This is what changes you and equips you to write an original, evidence-based essay, rather than a disjointed patchwork of other people’s thoughts. But this takes time and support.

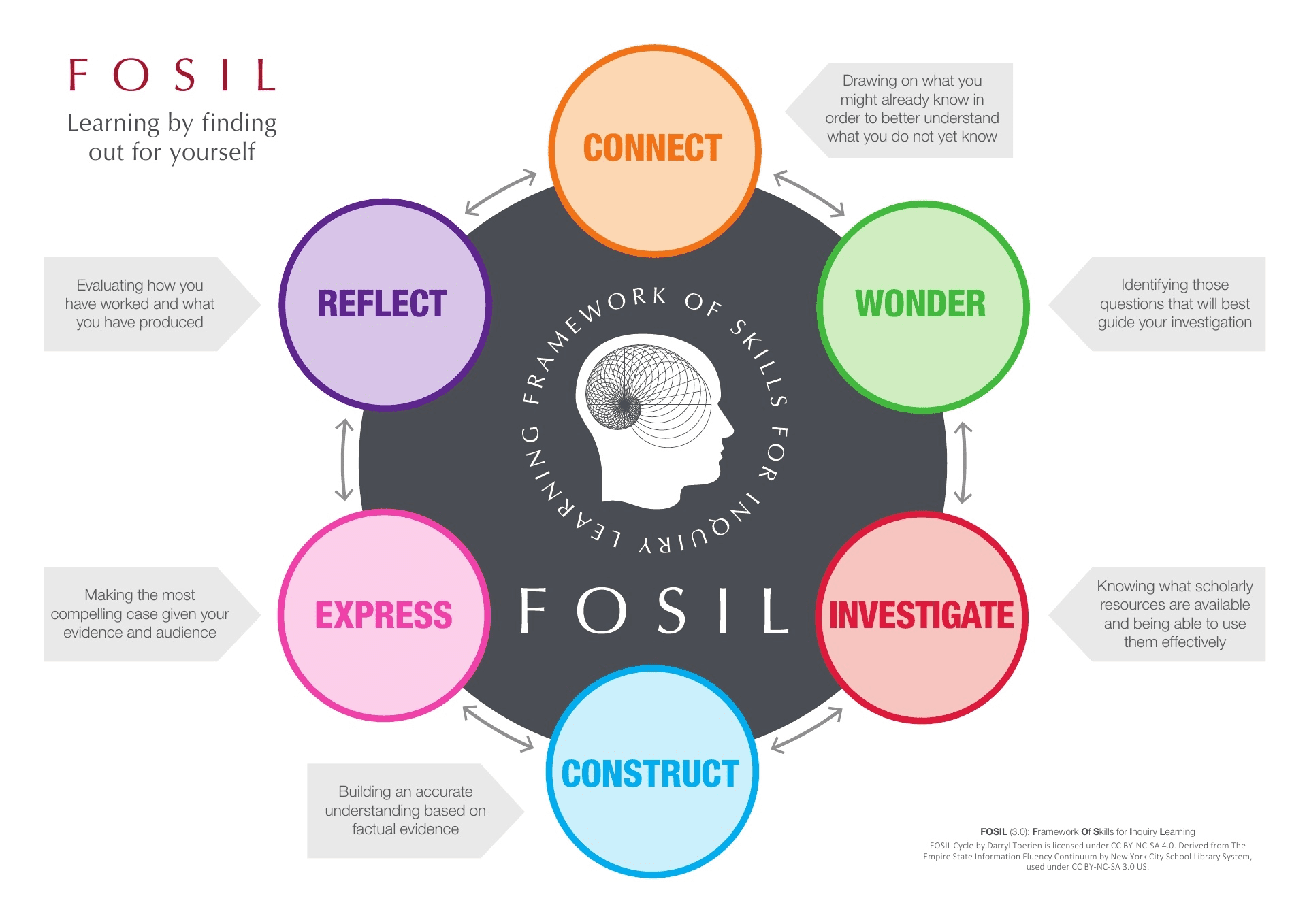

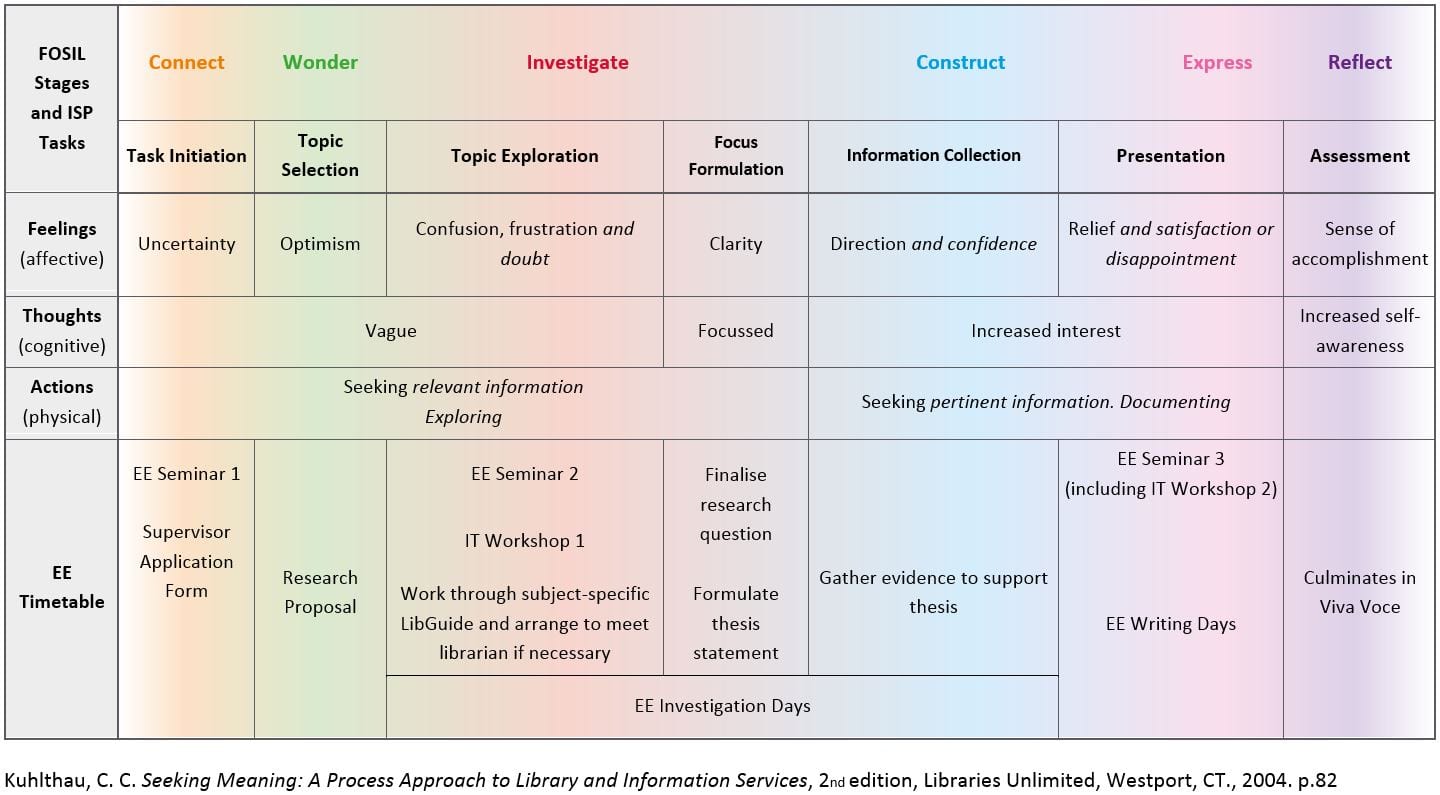

Our current timetable is based on a blend of Information Search Process and The FOSIL Cycle, developed by Darryl based on the Stripling Model of Inquiry within the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum.

The FOSIL cycle is a clear description of all the stages of inquiry, resting on a foundation of decades of research and it would require a blog post of its own to explain how the cycle works and the impact it has on teaching and learning – if you are interested visit the The FOSIL Group website for more information about the cycle, free downloadable resources and a community of educators sharing their ideas in our forum.

By understanding how the inquiry process works, we can guide our students more effectively through it. In this particular case we realised that students had almost no time for Connect and Wonder (the background research and exploration required to understand a topic well enough to ask good questions) and often skipped Construct (building understanding) altogether as they jumped from Investigate (finding out) to Express (writing).

Adding Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process, which described what students might be thinking, doing and feeling at each stage, into the timetable was the final piece of the puzzle.

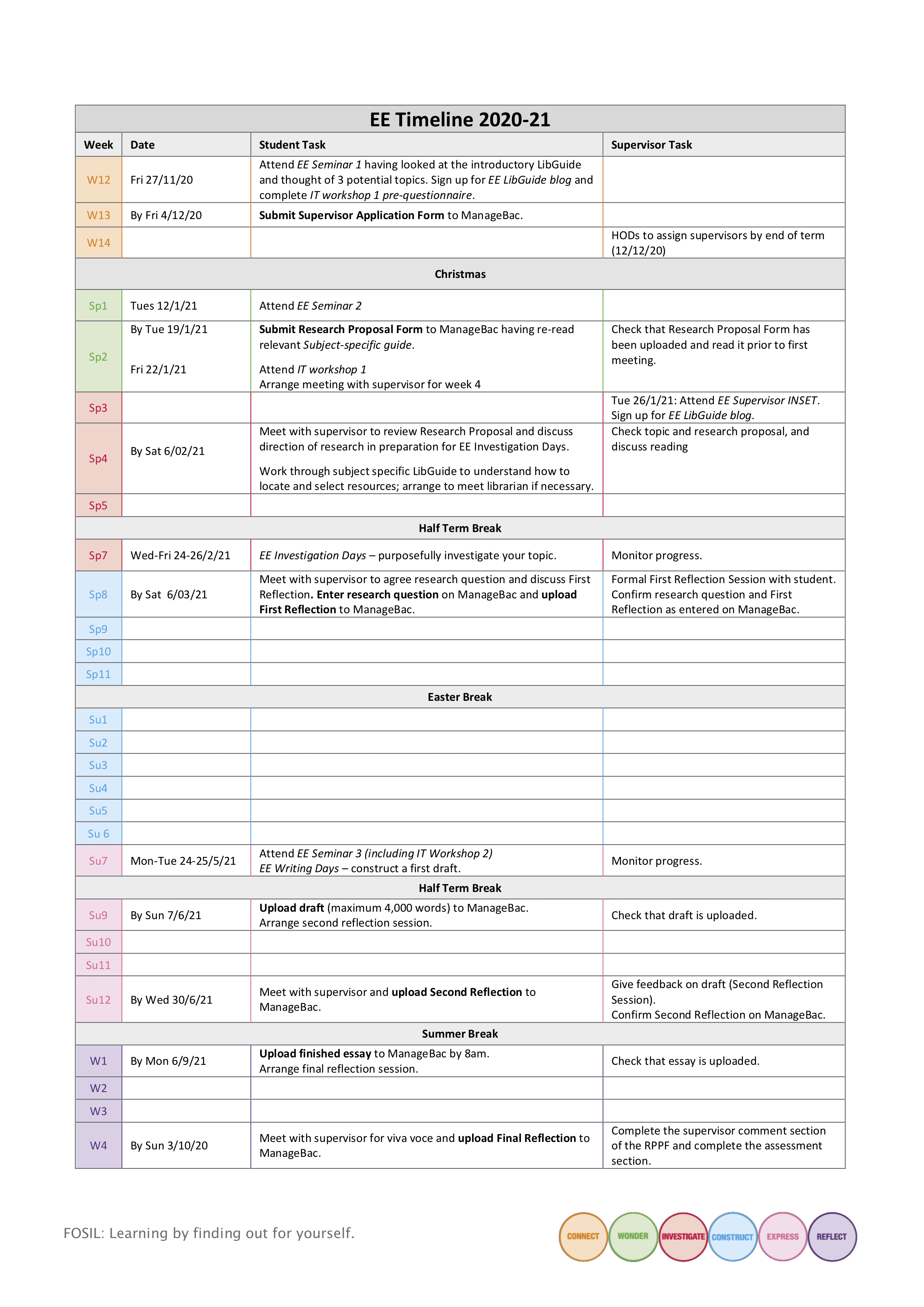

We began to understand how students might be feeling at different stages of the process and when the most appropriate times to offer support were. In terms of structured support (provided centrally to the whole cohort, as opposed to that provided by supervisors) we went from just one seminar at the start of the process to three, backed up by two dedicated IT workshops. We also split the Research Days into two chunks, giving students three Investigation Days off timetable to find resources and start working with them quite early in the process (February), with plenty of time to continue reading, follow up leads and acquire new resources, think through what they had read and discuss it with their supervisors in between that and the Writing Days (June). This Construct time is critical to helping students find their own voices. This is what the new timetable looks like in practice:

Hopefully you can see that this timetable is now informed by an understanding of the inquiry process and the student experience, rather than an administrative need for students to reach certain goals. The Library is also now integral to the EE process, not peripheral. This is the value of involving the Librarian in shaping the EE process.

Supporting the EE process

We now support the EE process through:

- Offering three compulsory targeted seminars at appropriate intervention points.

- Offering two compulsory targeted IT workshops at appropriate intervention points. As our provision has improved further down the school, we are finding more students arriving in the sixth form able to use the tools in Word to cite and reference and generate contents lists. This year we plan to offer parallel sessions for those who have never used these tools before and those who feel reasonably confident and just need a reminder.

- Supporting students in small groups and individually during the Investigation and Writing Days. It’s amazing how often students who thought they were pretty good at searching come out of these seminars surprised at how much they have learnt – if your library offers similar seminars it would be worth attending.

- Providing a web-based support resource (in our case a LibGuide) supporting students at every stage of the process. Our new EE LibGuide absolutely transformed our EE support last year, empowering students to access the support they need whenever they need it, moving through the process at their own pace. Having launched the resource in December 2019 with no idea of what was to come, the guide also enabled us to provide our strongest support ever, despite the coronavirus shutdown. We may continue to use some of the strategies we developed last year even after life returns to normal – for example using video tutorials for IT skills enables students to differentiate and self-pace and revisit in a way that live workshops do not, and allows them to choose PC or Mac based tutorials.

- Offering individual support as requested. We welcome individual requests by email or (before lockdown!) in person, and students often contact us for help finding resources on obscure topics and on citing different types of resources.

- Providing a broad and rich range of print and subscription resources, and purchasing new resources (or suggesting suitable alternatives) on request. Which leads us on to the third strand of the library service – and perhaps the one that springs to mind for most people when they think of the role of the library:

Resourcing the EE process

We have always emphasised using a wide variety of resources for in-depth research like the EE.

I. Books are perfect both for breadth – for reading around, becoming an expert in your topic and putting it into context. They are often (but not always) good academic sources, particularly when from well-known publishers, but you do still have to watch out for bias. Their biggest issue is the publishing time lag, which can mean it is harder to find a range of books about emerging issues, and the cost for niche academic texts.

II. Online journal articles often give very narrowly focussed depth (and can be very current) but have to be used carefully at this level because they can be too focused if you don’t have appropriate grounding in that area. Our most commonly used databases for the EE are EBSCO Advanced Placement source and JSTOR – and both have also proved invaluable last year for the range of ebooks they have during lockdown when the physical library was closed. We also saw increasing use of the Oxford Very Short Introductions ebooks, which offer the quality and depth of print books combined with the searchable convenience of online resources.

III. We have other subscription databases as well, and a third important category is targeted databases aimed directly at students at this level, which are increasingly starting to include video as well as print resources. We picked up the fantasticIdeas Roadshow’s IBDP Portal resource quite late in the process last year, when many of our students were already quite far into the investigation and were moving towards writing. As we approach the start of our EE process this year, I am confident that this innovative and exciting resource will really come into its own during the Connect stage of the FOSIL Cycle.

The short clips and compilations (each of which comes with an accompanying 1-page PDF providing lots of helpful information related to each video, including citing instructions) and the longer, in-depth conversations with world-leading researchers are ideal for students with a vague idea of the subject and perhaps topics they are interested in, but no clear direction. They are perfect for browsing and stimulating interest – and students who discover a line of inquiry that inspires them are assured of a one-hour detailed conversation with an expert in the field (with an accompanying PDF e-book) underpinning each clip or compilation to kick off their investigation!

Shaping you

As you can see from the above, although my role as a librarian does involve the traditional “librarian” activities of acquiring and curating resources, and helping my students to navigate them, it is actually so much bigger than that. I see my role directly as an educator. Perhaps more than anyone else in the school, it is the librarian’s job to nurture, enable and empower life-long learners because our subject is inquiry. I am not constrained by the need to teach my students to pass a Chemistry or Latin or Sports Science exam as well as teaching them how to think and learn independently – how to find, access, interrogate, assimilate, evaluate information and transform it into knowledge for themselves.

Not for me, not for the IB, not for the EE, not for their parents or their teachers. For themselves.

My students think I am supporting them through the EE, but my goal is so much larger. Done properly an EE can be a life changing experience that transforms a young person’s relationship with information and knowledge. It may well be the first time in your life when you realise that you have the power to turn yourself into an expert – when you realise that you know more about an academic topic than anyone around you, including your teachers, and that your thoughts and ideas matter.

I want to empower young people to question the narratives the world offers them, and to have the tools to seek authentic answers to those questions. I believe that the skills and attitudes that you learn through a relationship with your Library/ians during your school career will be vital for your success, not just at university but through the rest of your life.

As Ideal Libraries puts it:

“Libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin. The school may set the conditions for inquiry, encourage inquiry, and to some extent direct it, but learners must initiate inquiry for it to happen.”

You may think librarians spend all day hiding away in the library waiting patiently for someone to come in and ask for a book, but actually we’re hard at work (often late into the night) on changing the world, student by student. As the author and film-maker Michael Moore said of librarians back in 2002:

“They are subversive. You think they’re just sitting there at the desk, all quiet and everything. They’re like plotting the revolution, man. I wouldn’t mess with them.”

1) Oxford University Press. (2010) Librarian. In Oxford Dictionary of English, edited by Stevenson, Angus. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001/m_en_gb0468920

2) Oxford University Press. (2010) Library. In Oxford Dictionary of English, edited by Stevenson, Angus. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001/m_en_gb0468930

3) IBO (2018) Ideal libraries: a guide for schools. Cardiff: IBO. Retrieved 12 June, 2020, from: https://uaeschoollibrariansgroup.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/ideal-libraries-for-ib.pdf “

Post above edited to include an MP3 link to the audio of the Deep Dive conversation – the original link only worked if you already had a Notebook LM login.

Notebook LM

(This is the second of two posts – the first (above) is more generally about how I’m trying to deal with AI in school at the moment, this one is my experience of Notebook LM)

One of my issues with students using AI for revision and research is that AI still tends to hallucinate, and it can be difficult to tell where it gets its information from (although Google Gemini and Bing are better at providing examples of sources containing information similar to their answers than Chat GPT). If you don’t already know a fair bit about your topic it can be hard to tell whether the answer Is trustworthy – and if you did know a lot about the topic you probably wouldn’t be doing the research in the first place!

So Google’s Notebook LM felt like a bit of a gamechanger in this respect because initial claims suggested that you could upload a source (or several) and it would find answers just from those sources. A number of reviewers I saw enthused about its ability to synthesise sources and to spot patterns and trends. It seemed like it would be a safe bet for students wanting to do some revision by uploading their revision notes, or trying to understand a long, tricky research paper, so I thought I would give it a go.

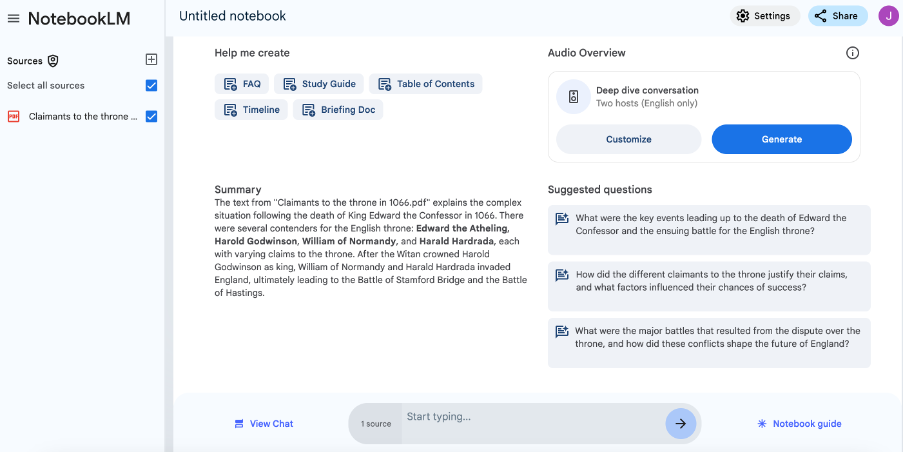

On first glance it is really impressive. I tried it with some notes from BBC Bitesize on the Norman Conquest for my Y7 son’s History revision. It offers options to produce FAQ, a study guide, table of contents, briefing document, timeline and a deep dive conversation (which is a podcast style conversational walk through of the source). It also generates a summary and suggested questions and you can have a chatbot conversation about your source. See image below. This was a fairly simple test of its abilities and all of the study notes looked pretty good – the kind of thing a student might produce for themselves but perhaps better (although I would argue that part of the value in producing these kind of revision notes is the work you do to produce them, so I’m not sure how helpful it would be for revision if the computer did it for you).

Where it started to get a little weird was the Deep Dive Conversation option. My 11-year-old son and I initially found it a little creepy how real this sounded, but he was very engaged and it was a new way to get him to interact with this revision material, with two ‘hosts’ having a very chatty conversation about the lead up to the Battle of Hastings. I was starting to feel more comfortable with this as a tool…until suddenly towards the end of the conversation it started to wander off the material I had given it. There was nothing obviously inaccurate (this is a very well-known topic so I wouldn’t expect glaring errors) but it started to mention events that were not in the text I had provided (my text ended with the Battle of Stamford Bridge, but the conversation went on to discuss the Battle of Hastings) and it was very clear that the conversation was not fully generated from that text I had given it alone.

This was a real concern for me, as part of the draw of Notebook LM was originally that I could be sure where the information was coming from, so I tried it on something trickier and fed it our newly revamped school library webpage to see what it made of that: https://www.blanchelande.co.uk/senior/academic/libra/

Again the results were impressive. It produced an accurate summary and briefing notes. The timeline was pretty weird and inaccurate – but it would be because this material is not at all suited for producing a timeline, so that was easy to spot. The 20 minute Deep Dive conversation that it produced caused me some serious concerns though. In some ways this had a certain comedy value, as the hosts became enthusiastic cheerleaders for our school in particular and inquiry in general, it was also weirdly impressive how they appeared to ‘grasp’ the value of inquiry learning in a way that many of our sector colleagues still have not done – and this went beyond just parroting phrases I had used.

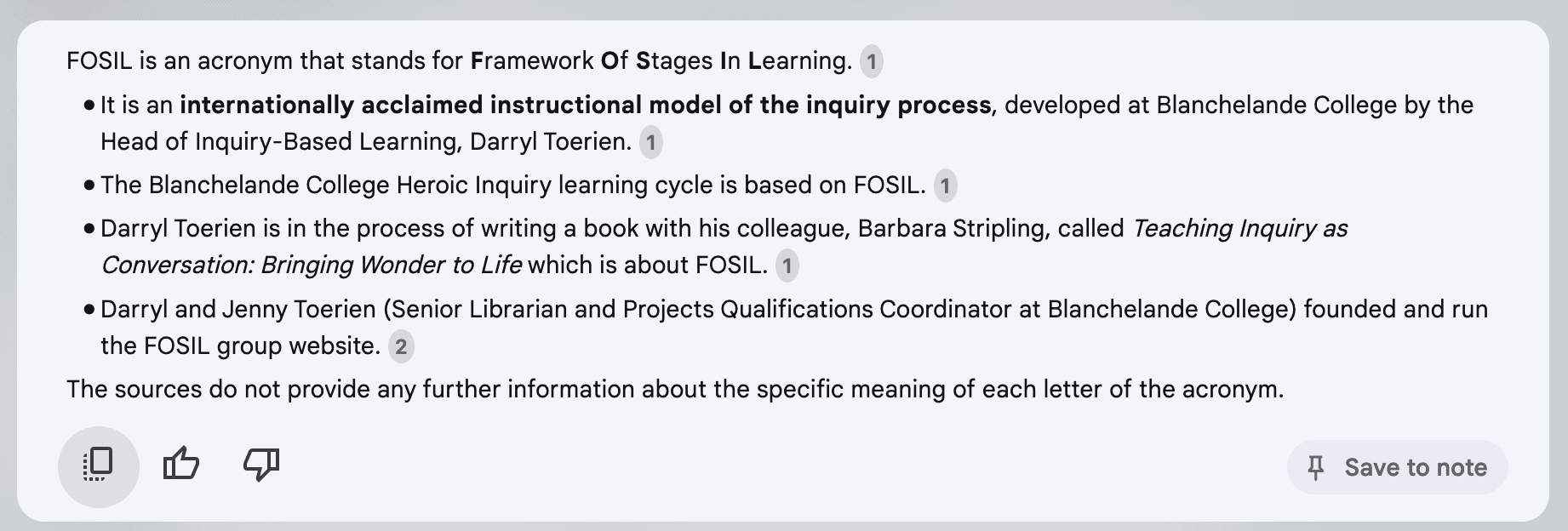

What REALLY troubled me though was that, because the page never actually said what FOSIL stood for, the AI completely made it up.

And it did it really well (try listening to the audio below from around about 2 minutes in). If we hadn’t known that it was talking complete nonsense there would have been no way to tell. According to Notebook LM, FOSIL stands for Focus, Organise, Search, Interpret and Learn (actually, as I am sure any regulars on this forum will know, it is Framework of Skills for Inquiry Learning). The AI then proceeded to give a detailed breakdown of this set of bogus FOSIL stages mapped onto the Hero’s Journey (which is mentioned on the site but I don’t give any details so that is also clearly drawn from outside). And it was really plausible – I might almost describe it as ‘thoughtful’ or ‘insightful’. But it was completely made up. Note also, that again, the final quarter of the conversation went way beyond the source I had provided and turned into a chat about how useful inquiry could be in everyday life beyond school. Very well done, and nothing too worrying in the content, but well off track from the original source.

EDIT: Deep Dive Conversation link – https://fosil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Blanchelande-Library-1.mp3 (original link required users to have a Notebook LM login. This one is just an MP3 file).

It is this blend of reality and highly plausible fantasy that makes AI a really dangerous learning tool. What if a student were using this for revision, and reproduced those made up FOSIL stages on a test? Or if we were using it to summarise, analyse or synthesise research papers? How could we spot the fantasy, unless we already knew the topic so well that we didn’t really need the AI tool anyway?

I tried asking in the chat what FOSIL stood for because with the Norman Conquest source the chat had proved more reliable and wouldn’t answer questions beyond the text. This time though it said :

Which is also subtly wrong but in a different way.

I wanted to love Notebook LM because I thought it had solved the hallucination problem, and the problem of using unreliable secondary sources, but it turns out that it hasn’t.

Caveat emptor.

(Speaking of buyer beware – Google says “NotebookLM is still in the early testing phase, so we are not charging for access at this time.” and I’ve seen articles about a paid version for businesses and universities on the horizon, so I don’t expect it to remain free for too long. It’s just in its testing phase where Google needs lots of willing people to try it out and help them to improve it before they can market it. So, to complete my cliché bundle – “if you aren’t paying for it, you are not the customer but the product”. I’m aware how ironic it is that I am saying this on a free website, but my defence is that we are all volunteers who are part of a community that is building something together, and not a for-profit company! No customers here, only colleagues and friends.)

Hi everyone, I’ve been meaning to return to this thread for a while. Ruth’s comment about Librarians being part of the conversation on AI is so important, and we do have to keep working to make sure our voices are heard here, with everything moving so fast.

Note that I’ve done so much thinking in the meantime that I’ve ended up with two quite long posts. One day I will learn to drop my thoughts in along the way to facilitate conversation better!

I still find trying to keep up with developments in AI exhausting (and often distracting), and I think part of the problem is that as information professionals we have a responsibility to think through the practicalities and ethics of AI in a way that early adopter classroom colleagues don’t always seem to. It’s relatively easy to throw out a cool new toy for your class to play with, but much more time intensive to work out how trustworthy, ethical and effective that tool actually is (even down to just making sure that the age limits on the tool you are recommending are appropriate for the class you are recommending it to).

I’m also finding the rate at which new tools get monetised frustrating – for example we designed a Psychology inquiry using Elicit last year, but just as the inquiry launched they changed their model and put certain features behind paywalls, which ruined large parts of the inquiry. So I’m a bit wary of recommending or designing anything that uses specific AI tools because the market is still evolving very fast.

So how to deal with AI (which we must – our students are growing up in a world where it has become the norm, so we can’t just ignore it!)? We’ve gone down the route of general principles, teaching healthy scepticism and trying to help students to navigate what it is actually good at and what it appears superficially good at but isn’t.

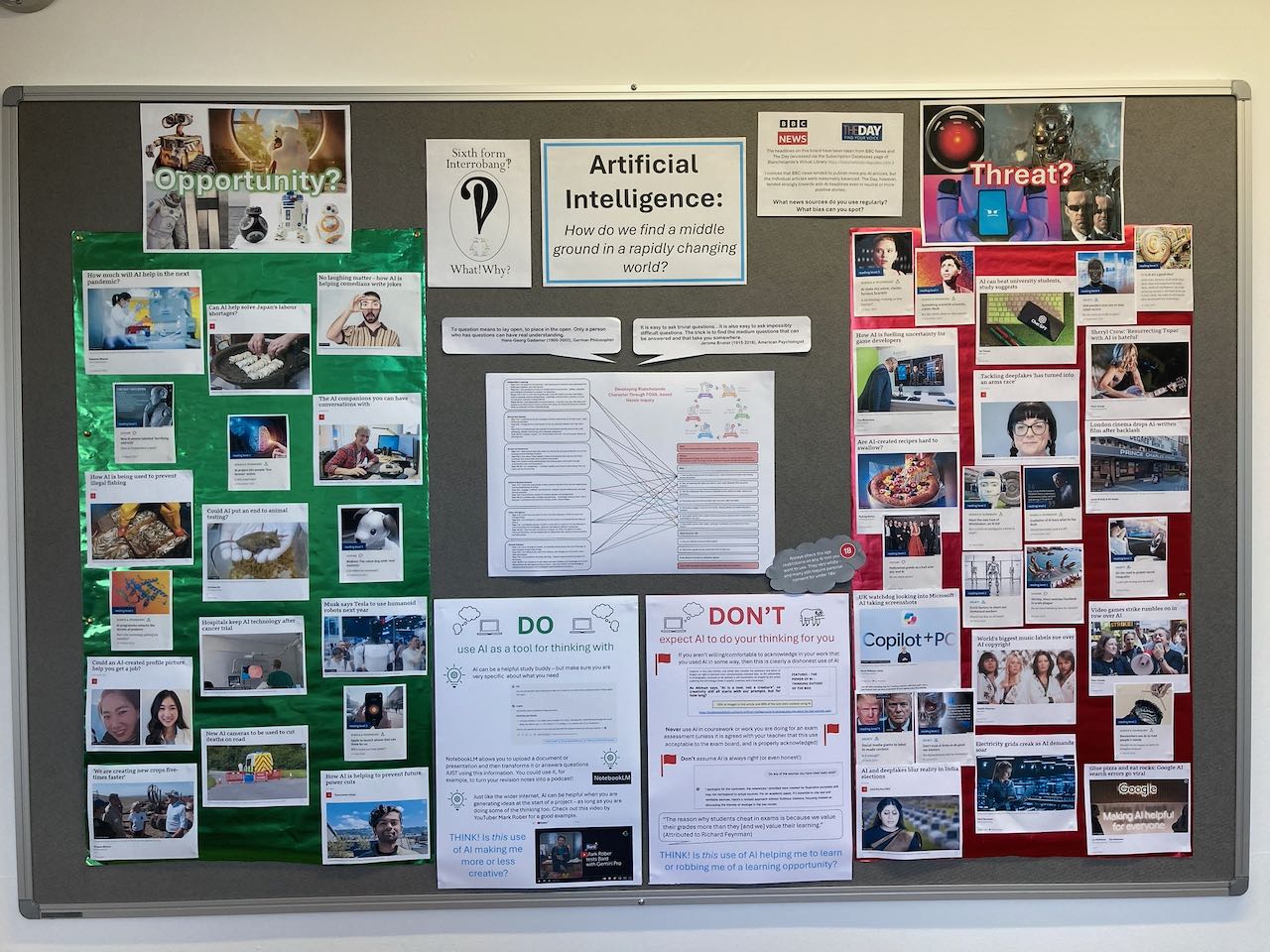

The image below shows a display I made at the start of term to support our Y12 Interrobang!? (inquiry-based Sixth Form induction) course. This is a six week course intended to prepare students for A-level study, and this year our inquiry focus was on AI and how the worlds of the different subjects they were studying were being impacted (positively and negatively) by AI.

If you zoom in, you’ll see that my advice on using AI tools boils down to:

- Do use AI as a tool for thinking with

- Don’t expect AI to do your thinking for you

- Ask yourself:

- Is this use of AI making me more or less creative?

- Is this use of AI helping me to learn or robbing me of a learning opportunity?

- Would I be comfortable to admit this use of AI (or might it get me into trouble)?

That last one is something I will also say to staff when we run a twilight INSET on AI in the classroom in a couple of weeks. As educators we have a duty to be transparent with students and parents, so if a teacher uses a site like Magic School AI to help them to write a letter about a school trip, or asks ChatGPT to generate some exam style questions then they should publically declare that. If we are embarrassed to admit our own use of AI then that is a clear indicator that we should not be using AI for that task. We cannot tell students that they are cheating if they use AI without declaring it, but then not hold ourselves to the same standard. These are the opportunities we need to be embracing to open up the conversation about how AI works and what it is good for (or not).

One example I would give of a potential positive use of AI is for a student who is making a website as an HPQ artefact. He isn’t particularly artistic, and art is not the focus of the website but he does need some copyright cleared images he can use to make his site more attractive and fit for purpose. I think that an AI image generator might be a good source for those images. The images are important to his product, but he is not being assessed on his ability to produce them himself, and he knows his topic well enough to know whether the images he produces are appropriate, and to adjust them if not. This use of AI would make him more creative than he could be on his own, is part of his learning experience and would be fully acknowledged.

Another example that I really wanted to love, but find myself feeling very ambivalent about is Notebook LM, which I will address in the next post.

Matt has started a series of posts about his exciting work on FOSIL and the AtL skills in his school in Stuttgart on this thread: https://fosil.org.uk/forums/topic/teachers-and-librarians-working-collaboratively . If you want to be part of that conversation, please continue it there.

Matt has continued posting about his exciting work on FOSIL and the AtL skills in his school in Stuttgart on this thread: https://fosil.org.uk/forums/topic/teachers-and-librarians-working-collaboratively . If you want to be part of that conversation, please continue it there. For other uses of FOSIL outside a full inquiry, do feel free to continue the conversation here.

Thanks for the update Matt – there is a great deal of exciting work here to delve into and we look forward to hearing where it goes. For those just joining this thread, there are two other historical threads that may be of interest:

- Integrating FOSIL with the MYP ATLs where Darryl and I documented our original attempt to do this at Oakham School

- Using FOSIL outside a full inquiry where Matt originally mentioned his school’s large-scale project to collaborate with teachers on the AtL skills

The five skill bands you have chosen to focus on are very important, and are clearly very much the province of the library, and I think that chosing to focus on these gives you a very clearly defined scope to your project that both makes it feel more achievable and helps you to track and measure your impact more effectively. The only caution I would give (that I am sure you are fully aware of and don’t need me to tell you!) is that these focus skills don’t exist in isolation. For example, we would always look at the Investigate skill of “Capturing information and thinking/notetaking” alongside Construct skills like “Claims/opinion and point of view” and “Interpretation and synthesis of information”. You’ll see this in the Investigative Journal and Cornell notetaking sheet. What you are doing is very sophisticated, Matt, so I’m sure you are well aware of this – the fact that you are focusing on one skill doesn’t mean you are ignoring the others. I’m really just flagging this for anyone who is reading this who is new to the process.

This is one of the key differences between information literacy and inquiry teaching. Information literacy is very focussed on individual skills, whereas inquiry acknowledges that these skills only really make sense as part of a framework of skills within a process, embedded within units with authentic learning outcomes (which might be subject based or extra-curricular but are never just skills for the sake of skills). This is exactly what you are talking about above, Matt, it’s just that your library is particularly invoved with certain skill sets.

What I am really interested in is your goal of monitoring student progress with these key skills, as up to now our particular focus has been embedding inquiry units within the curriculum all the way up our school, from Primary to Sixth Form, with particular focus on Signature Work inquiries where library staff are involved throughout the design (and sometimes teaching) so that we know that all children in key yeargroups have been exposed to a full inquiry cycle and had the chance to practise age-appropriate skills that can then be used in other subjects. This is quite a ‘top down’ planning approach. I am really interested in your ‘bottom up’ approach of tracking certain skills with individual students and determining who needs intervention, and would love to hear more about how this goes. You might find the New York State Infomation Fluency Continuum Priority Skills assessments helpful for this (although I know there are particular assessment points within the MYP which will also help). FOSIL is based on the NYSIFC, and these priority skills assessments inform our graphic organisers. Part of the difference is that the FOSIL graphic organisers focus on stages of the process, and often combine several skills in one organiser, while the NYSIFC organisers are focused on one skill per organiser, which may be more what you are looking for at the moment.

I definitely agree with your approach of being happy to work with any teacher on any unit where a skill is being addressed rather than waiting for the perfect unit. This has always been our approach, and often leads to wider collaboration further down the line. The more we can get involved with individual teachers in small ways, the more we can spread and support inquiry skills throughout the curriculum. Skills need reinforcement little and often, rather than just the odd big ‘project’ (although full inquiries are really important and we can’t abandon them entirely).

We’re really excited to see where your work goes. If you are looking for tools further down the line to help you to track skills across different units and to track student self-assessment I would recommend having a look at Mondrian Wall and didbook. (This is an entirely personal recommendation – we don’t do sponsored recommendations on this site!). We spent a lot of time working with Kevin Heppell, the director of the the parent company, Sequential Systems, when we were at Oakham and he is someone who is really passionate about education and young people and creating tools to help schools and students to develop and understand their educational identity. You can see a presentation he did to the IFLA School Libraries Section 2022 Midyear meeting here, about creating a dynamic curriculum map. This is a whole school tool, and your school may not want or need something like this yet, but what you are doing is very sophisticated and has huge potential so it is worth being aware at the outset that a tool like this exists so that you can start including it in your conversations with senior management if it might be helpful.

Please do keep us all posted about your progress. Building this sort of evidence-base to demonstrate impact is such important work.

Lessons vs seminars

My background is in Science teaching and, even since becoming a Librarian, I have been to a lot of teachmeets, so I understand how to structure a lesson – that you need planned changes of activity including ‘led-from-the-front’ discussion, group and paired work and individual work, and transitions between these. Plenty of opportunitues for modelling, discussion, practice, feedback and reflection.

My mistake going into EPQ lessons was that I was coming out of an IB EE system where in total over the course of the whole year I only had three one hour seminars (for the whole cohort at once, which was around 100 students) and two half hour ICT workshops with smaller groups. Of necessity these sessions tended to be lecture-style, pointing students to the resources they needed and hoping they would access them later. For the EPQ I had a one hour ‘lesson’ every week with just 4 or 5 students. However, I think (possibly partly because it was such a small group) I initially treated that as more of a lecture/conversation-based seminar rather than a more structured lesson. This meant we could go over a lot more content (still supported by a LibGuide that they could look back at in their prep time) but I was frustrated by how little of the skills and techniques we had discussed in lessons they seemed to be carrying over into their projects. I think I expected them to be able to apply what we had done in the lesson to their own projects in their prep time, in a way that perhaps I wouldn’t have expected as a Physics teacher if I hadn’t given opportunities to practise in the lesson.

The breakthrough for me in terms of how I view my lessons was starting the HPQ. I had a slightly larger group of younger pupils than the EPQ, and my lessons (for timetable reasons) were structured as two half hour sessions a week rather than a single one-hour session. One was in the Library during tutor time and the second was in a classroom with computers during the lunch hour. For this second session, the students tended to arrive at very different times so it rapidly became clear that it could not be a group teaching session and instead would need to be time for them to apply what we had been learning to their own projects, with me around to support and encourage them. This was the point at which I discovered how hard they found this, and how much individual ‘coaching’ was necessary. It’s important to say at this point that this in no way impacted on the independent nature of the qualification – they still needed to make their own decisions, find their own resources and shape the direction of their own projects, but I was able to play the role of coach and critical friend (note: I supervise all the HPQ students, but the EPQ students have their own supervisors – I am the co-ordinator and deliver the taught course for both groups).

Seeing how well this worked for the HPQ, I also started to scale back the amount of content in my EPQ lessons and tried to make sure there was time in the second half of the lesson for students to work on their own projects. This allowed for more individual conversations and really helped the students to understand how to apply the skills we had been learning to their own projects. It was an important reminder to me of one of the vital principles of inquiry (and good teaching generally) – the students should be working at least as hard as the teacher during the lessons. I also tried to incorporate more group tasks into the first half of the lesson, based on ‘dummy’ projects I had set up. E.g. for a lesson on refining the research question, the group are given the titles of a number of articles relating to a fictional research question and need to work together to group them by topic, put these topics in a logical order and then decide whether the research was really answering the original question or whether the question needed to be refined. Students find this much easier with a fictional topic than with their own, because the emotional investment isn’t there, so they are less attached to the initial question.

A couple of very successful lessons I have had this year have also been entirely self-paced (using a combination of the LibGuide and Teams). In one case this was because my son was ill and I was at home taking care of him, so was running the lesson remotely (flashback to COVID days!), and in another because I knew the students had very different skill levels for that particular topic so I wanted to let them work at different paces. Co-incidentally these lessons were the two that we used to run ICT workshops for for the IB EE students (citing and referencing, and setting up a Word template for the final report). The self-paced lessons were much more sucessful than ‘from the front’ guided workshops and I was much more confident that the students had practised and understood the necessary skills. It also meant they could revisit them at any point. If I ever had to deliver the EE ICT workshops again I would do them like this! I’ll provide more detail in a future post in case that is helpful for anyone.

So, in summary, the first lesson I have learnt is not to try to pack too much into each session, to vary activities and particularly to allow structured and supervised time for students to work out how to apply the lesson to their own projects.

-

AuthorPosts