Darryl Toerien

Active 3 days, 3 hours agoRole: Head of Inquiry-Based Learning

Town/City: Guernsey

Country: United Kingdom

Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

28th October 2025 at 9:49 am in reply to: SJSU 2025 | Leap 2 | Teaching Inquiry as Conversation #87920

Unfortunately, I was not able to make it across, but Barbara said that the presentation was very well received, and that all the sessions were very good.

Like with Leap 1, I hope that they will make the proceedings available online, which I will share here if they do.

For an informative overview of Leap 1, see Leap into the Future of School Libraries International Conference by Charlene Petersen for the Canadian School Libraries Journal.

27th October 2025 at 3:09 pm in reply to: SJSU 2025 | Leap 2 | Teaching Inquiry as Conversation #87918Our presentation — Teaching Inquiry as Conversation: Brining Wonder to Life — is now available as a free PPT download.

—

24th June 2025 at 1:08 pm in reply to: Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86956

24th June 2025 at 1:08 pm in reply to: Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86956On Thursday, 19 June, we held our third annual Year 9 Signature Work Inquiry Celebration.

As I explained to parents, the Signature Work poster is similar to an article’s Abstract, in that it both summarises a larger body of work and reflects a learning journey that is itself embodied and situated.

This year I gave parents an overview of what this learning journey entailed: deeply thoughtful reading into a personally-chosen topic related to the theme; a 1-minute speech in English; a 2-minute speech in Geography; a 750-word essay plan overview; an essay plan; a handwritten draft essay; a typed re-draft; a typed re-draft in response to feedback, and; cue cards for the 5-minute speech in English.

As is customary, one student was chosen to represent Year 9 with their speech, and this year we could not be prouder of Flo.

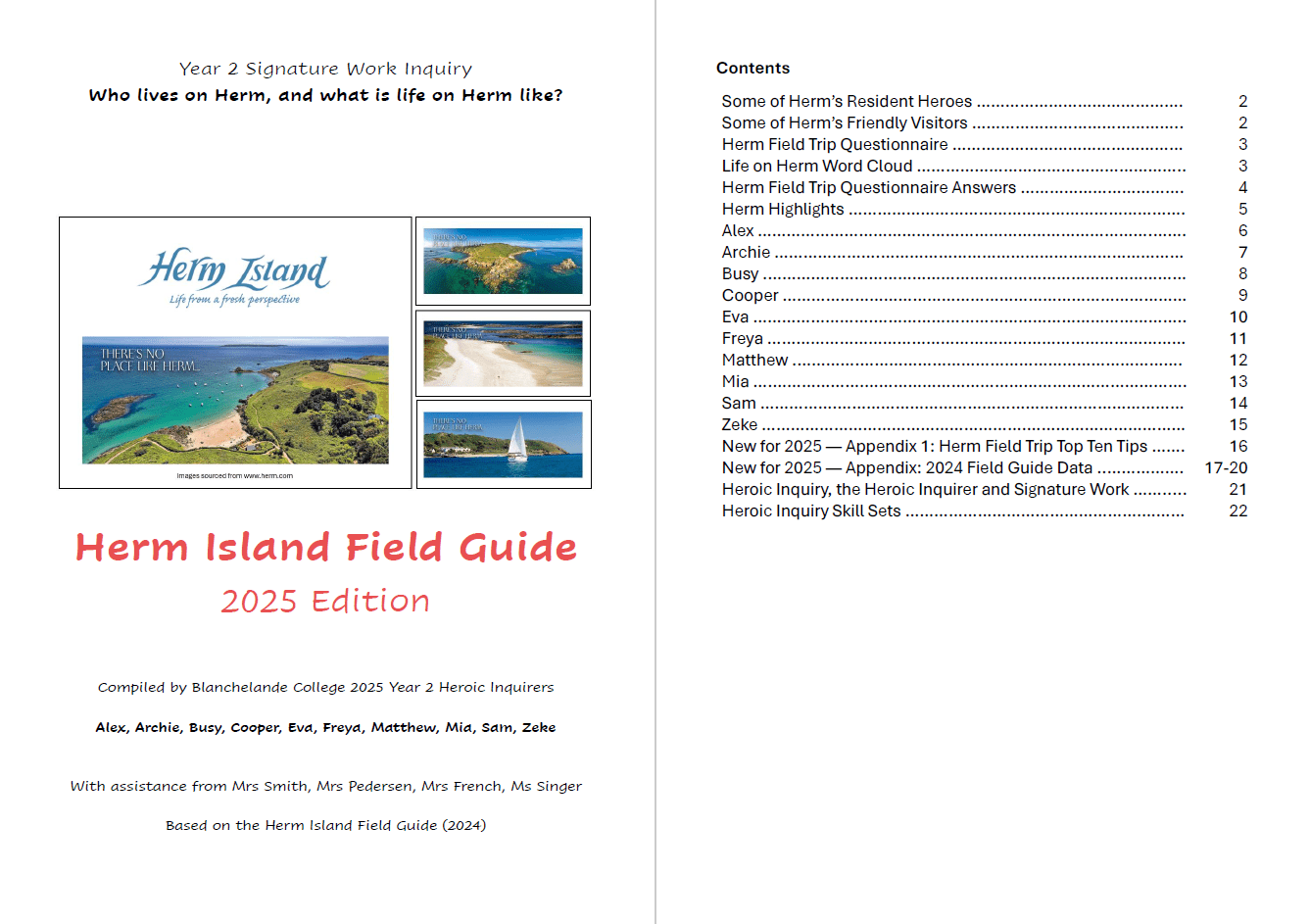

24th June 2025 at 11:42 am in reply to: Year 2 (Grade 1) Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86951

24th June 2025 at 11:42 am in reply to: Year 2 (Grade 1) Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86951On Wednesday, 18 June, we held our second annual Year 2 Signature Work Inquiry Celebration.

Herm is a very special place, made more so by the very special people who live and work there, and the purpose of the Year 2 Signature Work Inquiry is to build knowledge and understanding of what life on Herm is like, for both residents and visitors.

We were delighted to be joined by Shaun McDonald, General Manager of The White House Hotel, and Alison Veitch, Head Chef.

I realise now, to my shame, that I did not share highlights from last year’s Field Guide; however, I share highlights from this year’s Field Guide instead. The Field Guide is published by the Library and presented to staff and students who took part in the Field Trip, as well as the residents who we met.

Thanks, Ruth and Elizabeth.

I’ve just read a very interesting article by Peter Michael Gratton, called The Banality of Complicity: Arendt’s Guide to Moral Resistance in the Age of Trump, in which he discusses Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963) and subsequent lecture in 1964, Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship.

Gratton observes that Arendt’s lecture “is uncanny in precisely identifying the psychological and moral patterns of capitulation [to] and cooperation [with authoritarian systems] we see playing out today,” and it struck me that there are parallels with the uncritical and wholesale embrace of AI. For example:

Equally troubling [to the alarming speed with which moral standards can be inverted overnight] is Arendt’s insight into how readily people surrender individual judgment to systems. … The lecture isn’t [however] some grandstanding harangue about the need for heroism. Instead, she makes clear that resistance begins not with heroic action but with the simple refusal to participate in the regime and its lies, as well as the comfortable self-deceptions that make complicity possible. … Having knocked down the last of the excuses of the complicit—what else was I to do?—Arendt can move to the central claim of the lecture: that “obedience” always amounts to support, no matter what we tell ourselves to sleep at night. … What makes Arendt’s [lecture] so profound is that she locates resistance not in grand gestures requiring extraordinary heroism, but in preserving one’s capacity to think independently and refuse complicity in evil even when everyone else has capitulated. We cannot control the circumstances we inherit—so many never asked for this—but we always retain the power to withhold our support from systems that violate human dignity. And in that vital first act of defiance lies the seeds for resisting the reality in which we find ourselves today.

Edit:

I would say that reality is what we have to deal with, and that success is dealing with reality, which is not to say that dealing with reality doesn’t alter the reality we have to deal with.

From the conclusion to my article, “the revolution, and the unfolding resistance that must now precede it, will not be televised brothers and sisters, because the revolution will be live.”

11th March 2025 at 3:05 pm in reply to: Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #85777In Defence of the Essay

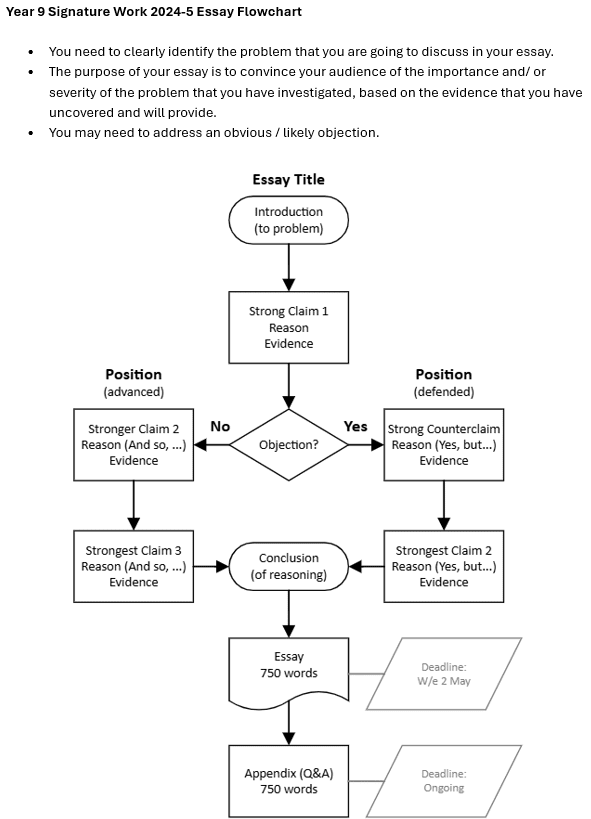

We have reached the point in the Year 9 Signature Work inquiry where we shift our focus from thoughtful reading to thoughtful writing, which will take the form of a 750-word essay in which students will (a) clearly identify and define the problem that they intend to discuss, and (b) attempt to convince their audience of the importance and/ or severity of the problem based on evidence that they uncovered during their investigation and will present in their essay.

Why, one might ask, as some do, teach students to write an essay if AI can write a better essay? Now while there may be more to this question than at first appears, it is, as asked, a question that demands an answer.

The simple answer is that we are not, in fact, teaching students how to write an essay, but to think, with the essay in this case being a tool to think with, and a particularly powerful one at that.

This distinction may seem pedantic, but is, in fact, profound, especially as AI intrudes its way into every aspect of our lives.

As Christopher Newfield (2025) writes:

My root worry about AI has always been that while it was making machine learning better, it was also making human learning worse. I am not alone in this. Teachers, who are responsible for helping students think, were increasingly furious about what AI was doing to the student brain.

A week before ChatGPT was released, Jane Rosenzweig, director of Harvard College’s Writing Center, made what should be an obvious point: “Writing—in the classroom, in your journal, in a memo at work—is a way of bringing order to our thinking or of breaking apart that order as we challenge our ideas. If a machine is doing the writing, then we are not doing the thinking.”

…

I draw several conclusions here.

…

Second, the high-value economic benefits of AI require fully empowered human use of AI as tools. Benefits will depend on society devoting much more effort than it now does to the expansion of human capabilities, rather than seeing technology as rescuing society from the self-inflicted enshittification of its human systems. The rigourous teaching of writing and thinking is more essential than ever.

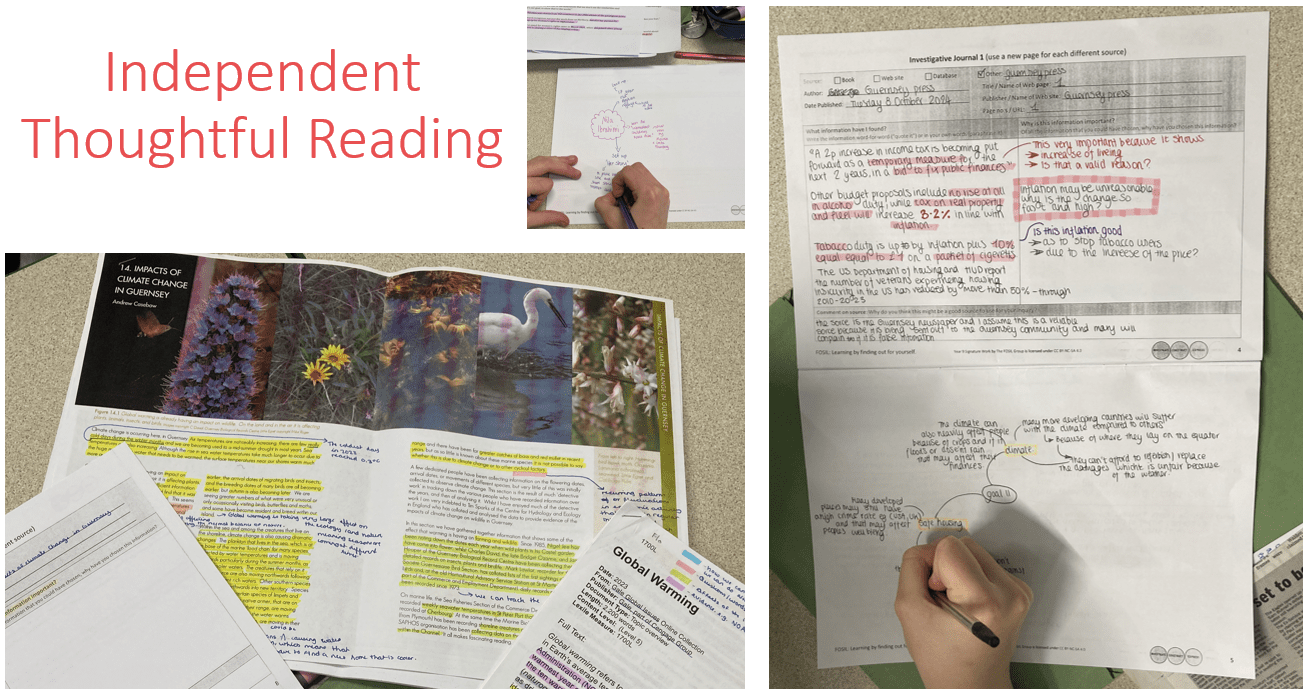

Students have now spent a term investigating a SDG-related problem that they have identified and defined, which is a distinguishing feature of Signature Work inquiry. I have been deeply impressed by how purposefully many students in this cohort have used their Investigative Journals as tools to think with.

The next step, however, is daunting, even for university-level students, which is why there is real value in helping students with this in school. As Newfield (cited above) explains:

I learned during my decades of teaching university-level writing that students can mostly find a general topic that interests them. But they struggle with the next question: what do you want to say about your topic? What’s your thesis, your claim, about it? This stage turns out to be very hard, and the simple reason is that it’s where independent thinking has to happen. It’s where the student diverges, however slightly, from what has already been said. If a GPT product is available, the student—or anyone, myself included—will be tempted to use it to skip this thinking stage.

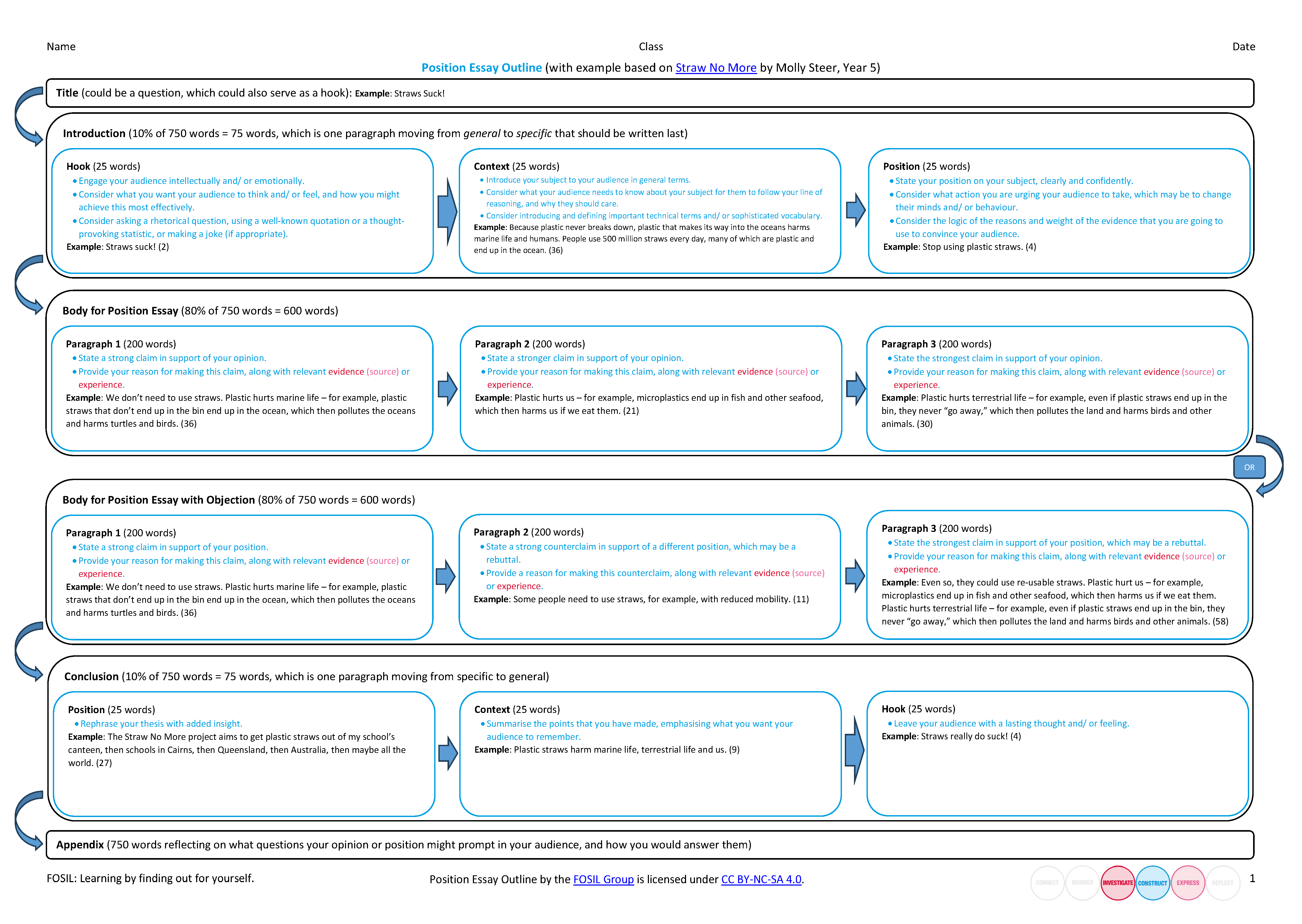

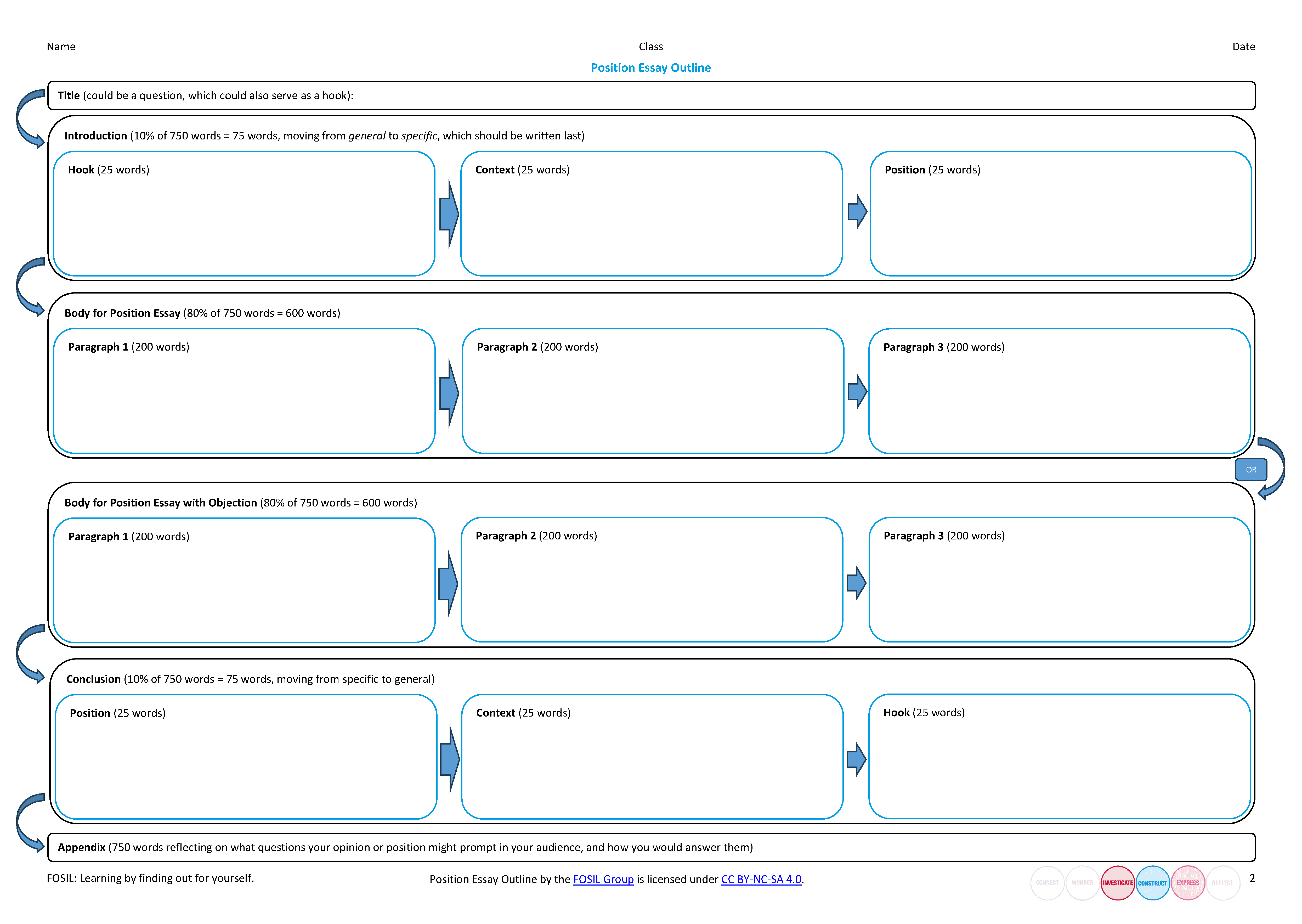

To help students with this last year, I developed the Opinion Essay and Position Essay flowchart and graphic organiser (see post #83043 above). This year I have simplified the flowchart and graphic organiser slightly (see below), and also added an example to the graphic organiser based on the Straw No More presentation by Molly Steer at TEDxJCUCairns (2017), which we looked at in class.

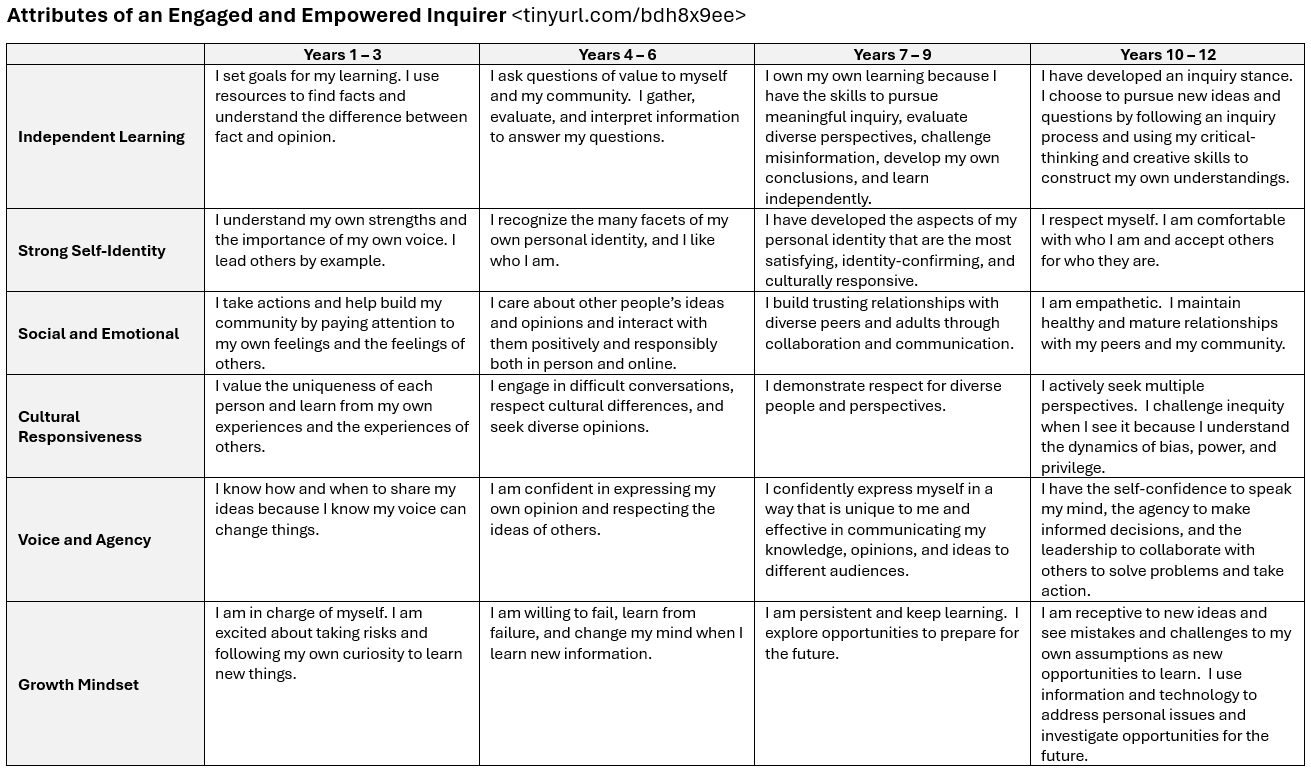

This is the critical moment, as Newfield highlights above, when students become more fully themselves, or less, as they face twofold temptation of letting the machine [and its programmers] think for them and speak for them–as Janet Salmons (2025, emphasis added) warns, “the implicit message [of AI offering to (re)write for you] is less than subtle: use the words we tell you to use, in the style we tell you to use, to say what we tell you to say, in the voice we tell you to use,” which is bringing about a “‘flattening’ of contemporary writing.” This is when I must trust that I have sufficiently “encouraged [my] students to engage in the process of acquiring knowledge, which is a very difficult process, [without which] all you get is memorisation and reproduction in tests” (Young, 2022), or in this case, copy & paste. This encouragement to engage–to Connect–takes time and energy, to be sure, but time and energy well spent on enabling my students to develop as engaged and empowered inquirers, increasingly willing and able to learn for themselves.

My confidence is high.

References

- Newfield, C. (2025, March 4). The Fight About AI. Retrieved from Independent Social Science Foundation: https://isrf.org/blog/the-fight-about-ai

- Salmons, J. (2025, January 28). Finding Your Voice in a Ventriloquist’s World – AI and Writing. Retrieved from The Scholarly Kitchen: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2025/01/28/guest-post-finding-your-voice-in-a-ventriloquists-world-ai-and-writing/

- Young, M. (2022, September 21). What we’ve got wrong about knowledge & curriculum. (G. Duoblys, Interviewer) Tes Magazine.

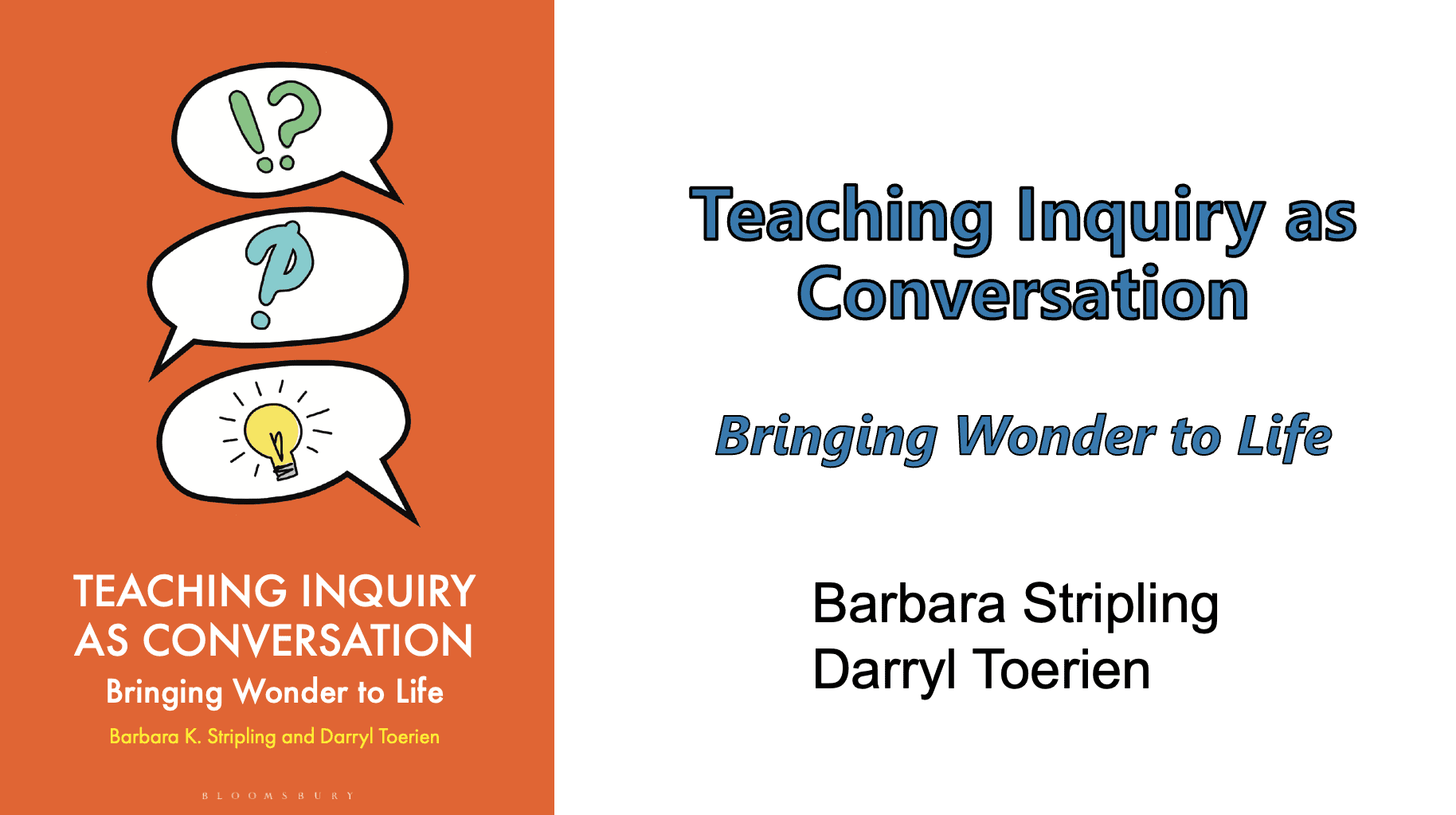

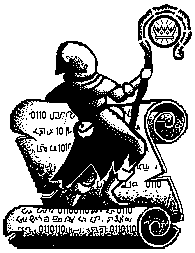

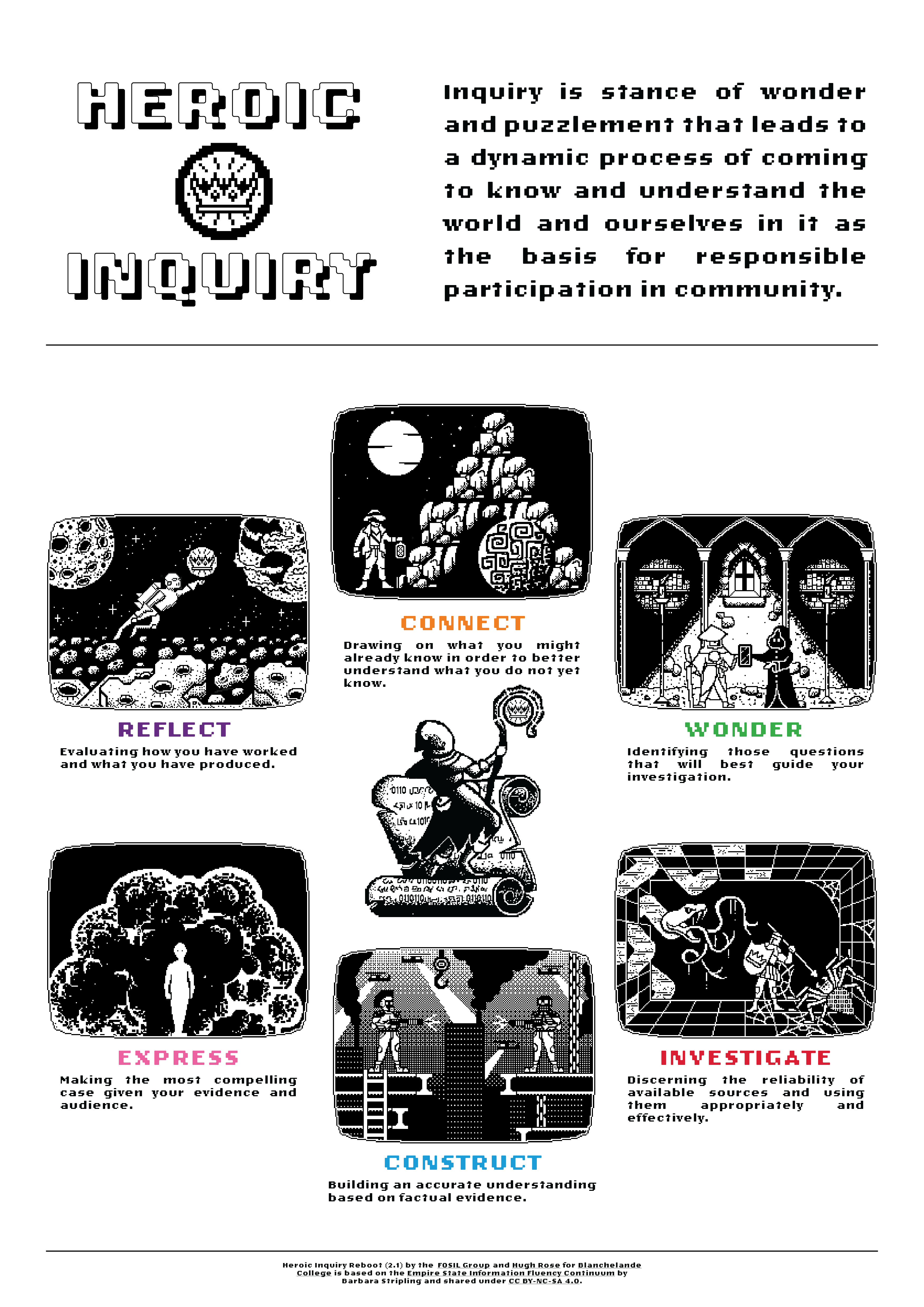

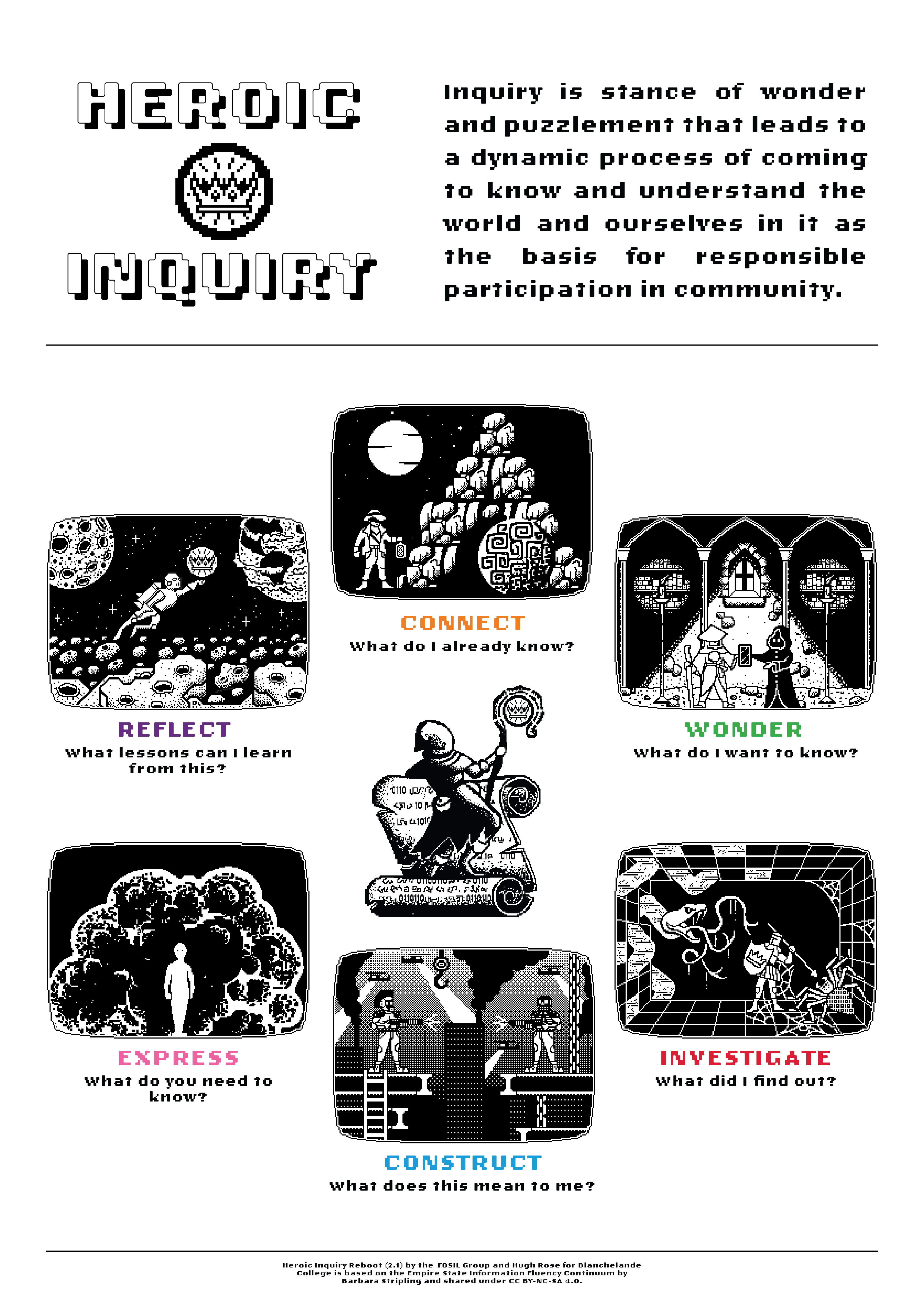

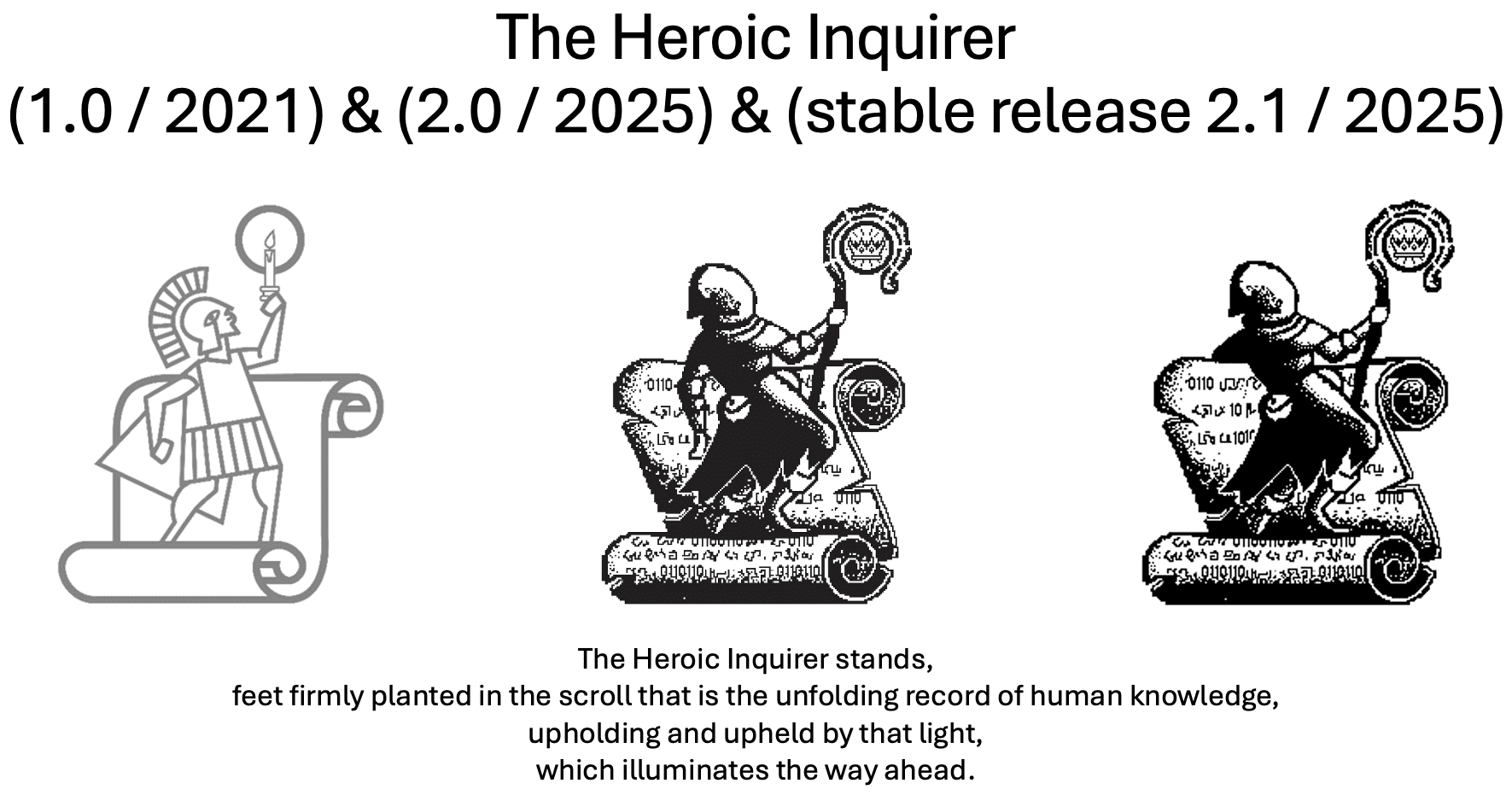

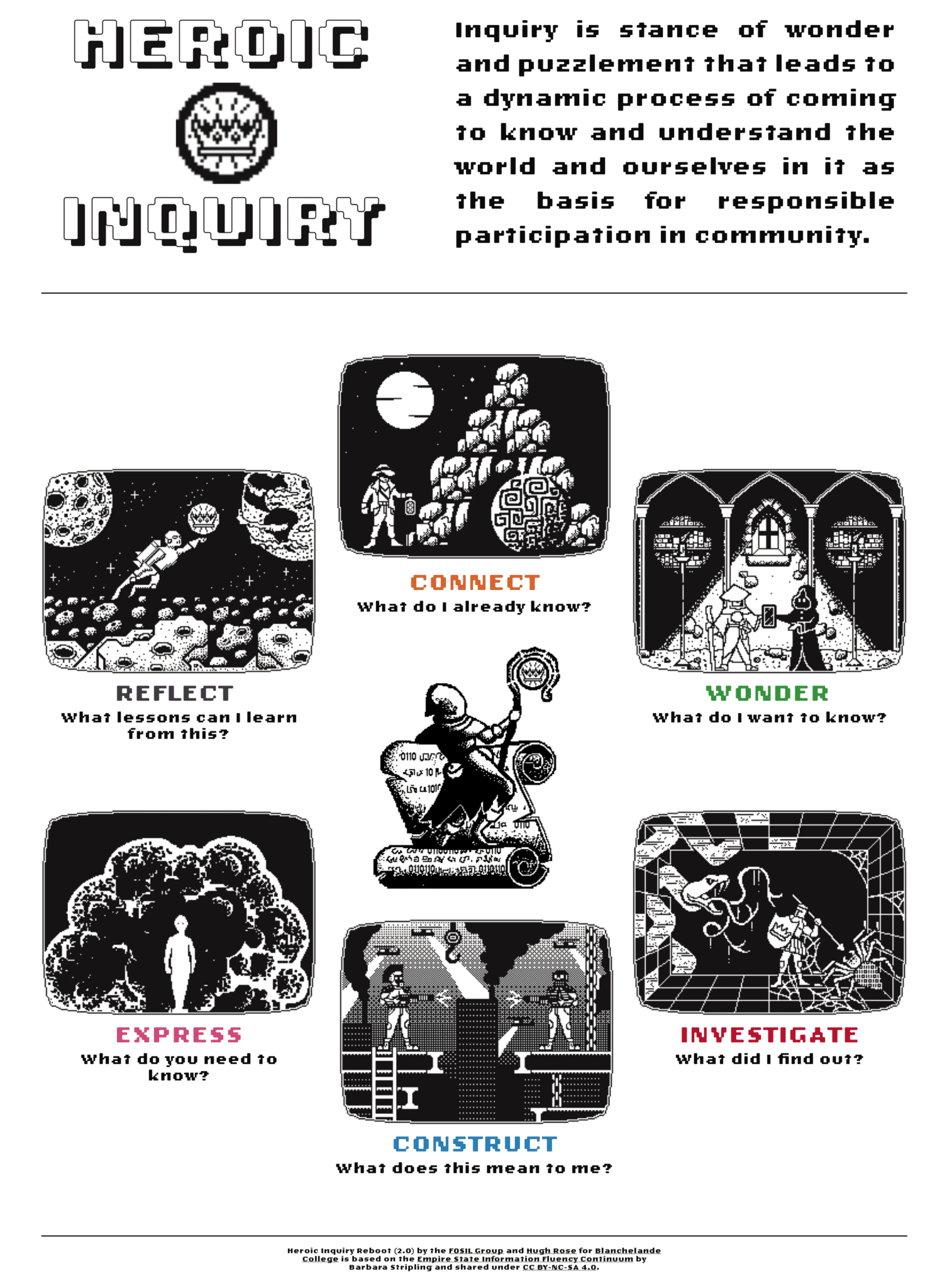

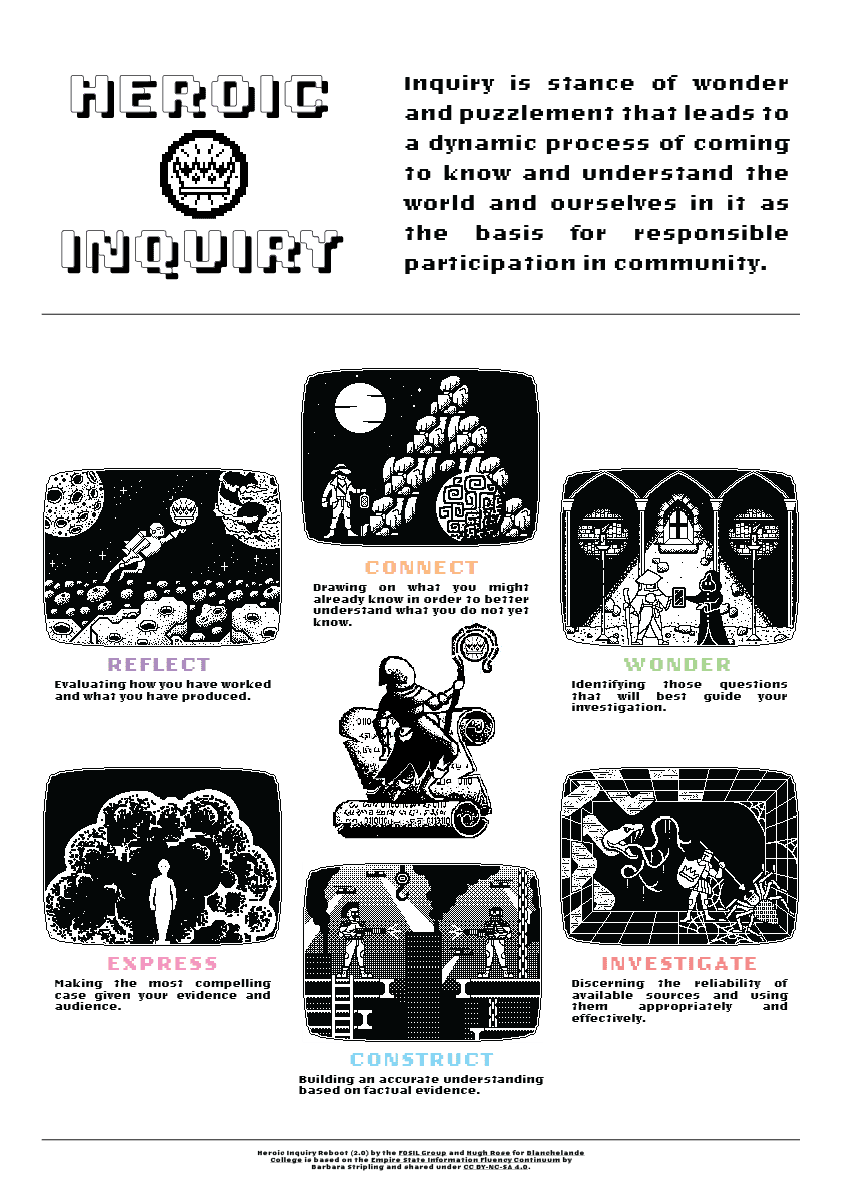

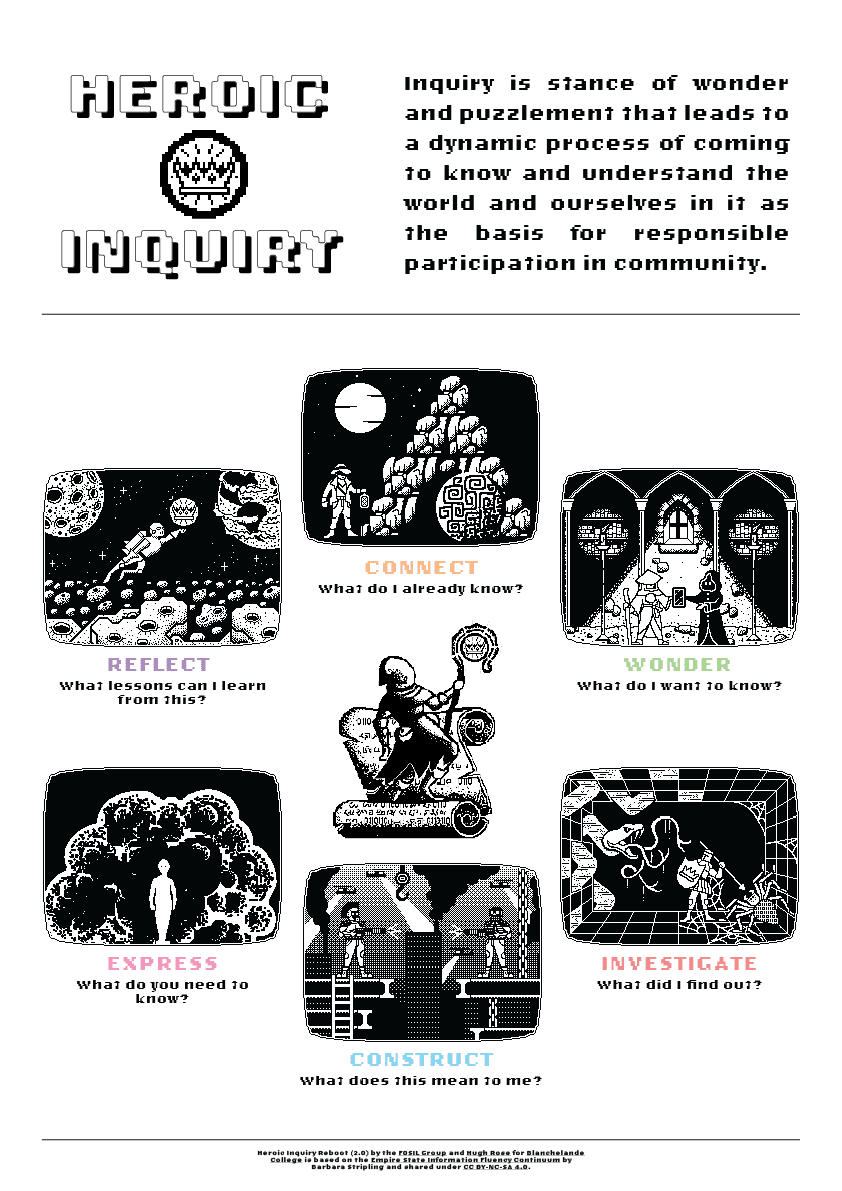

28th February 2025 at 10:35 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85696The CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 stable release of Heroic Inquiry (2.1) is now available for download:

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

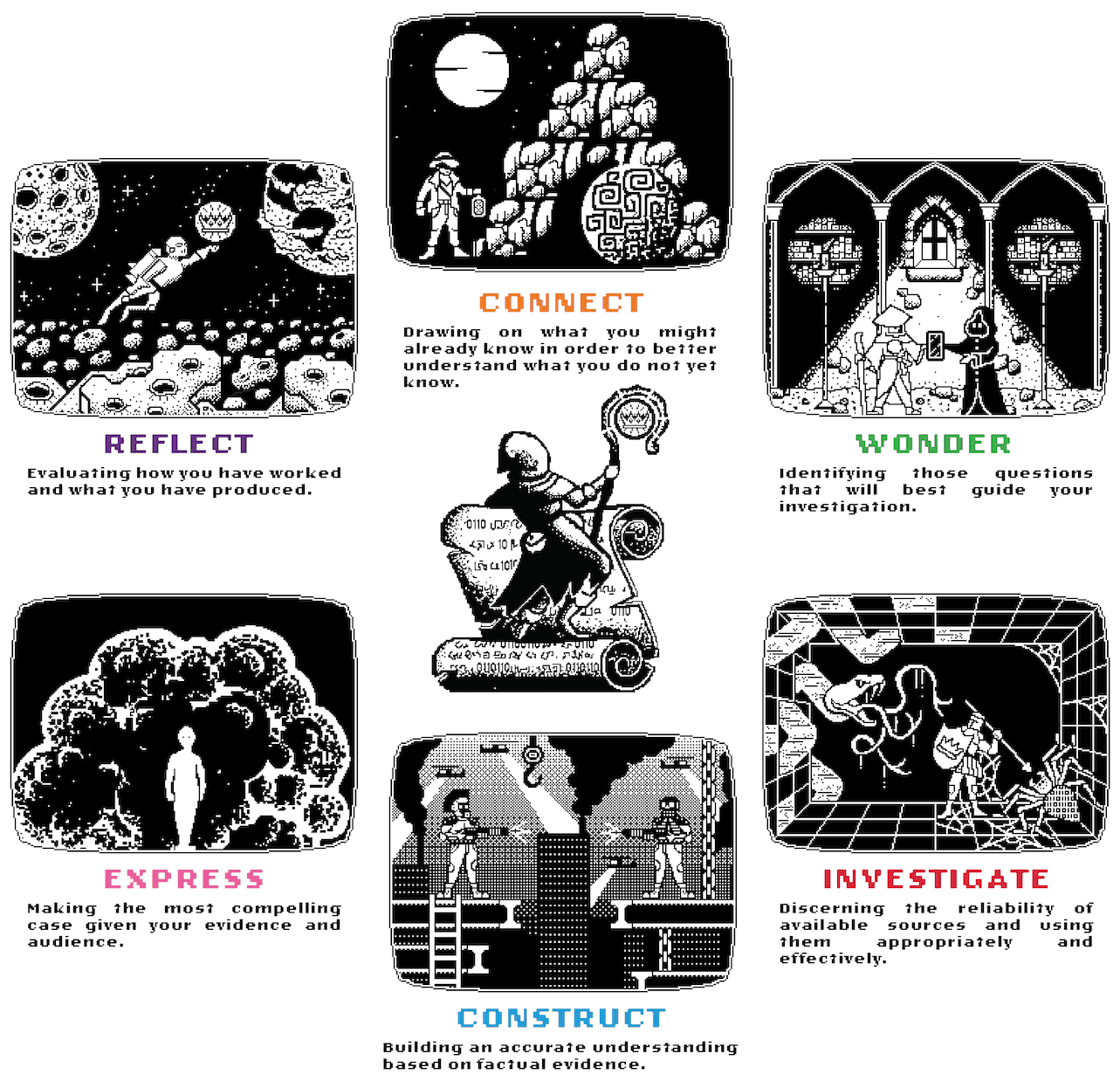

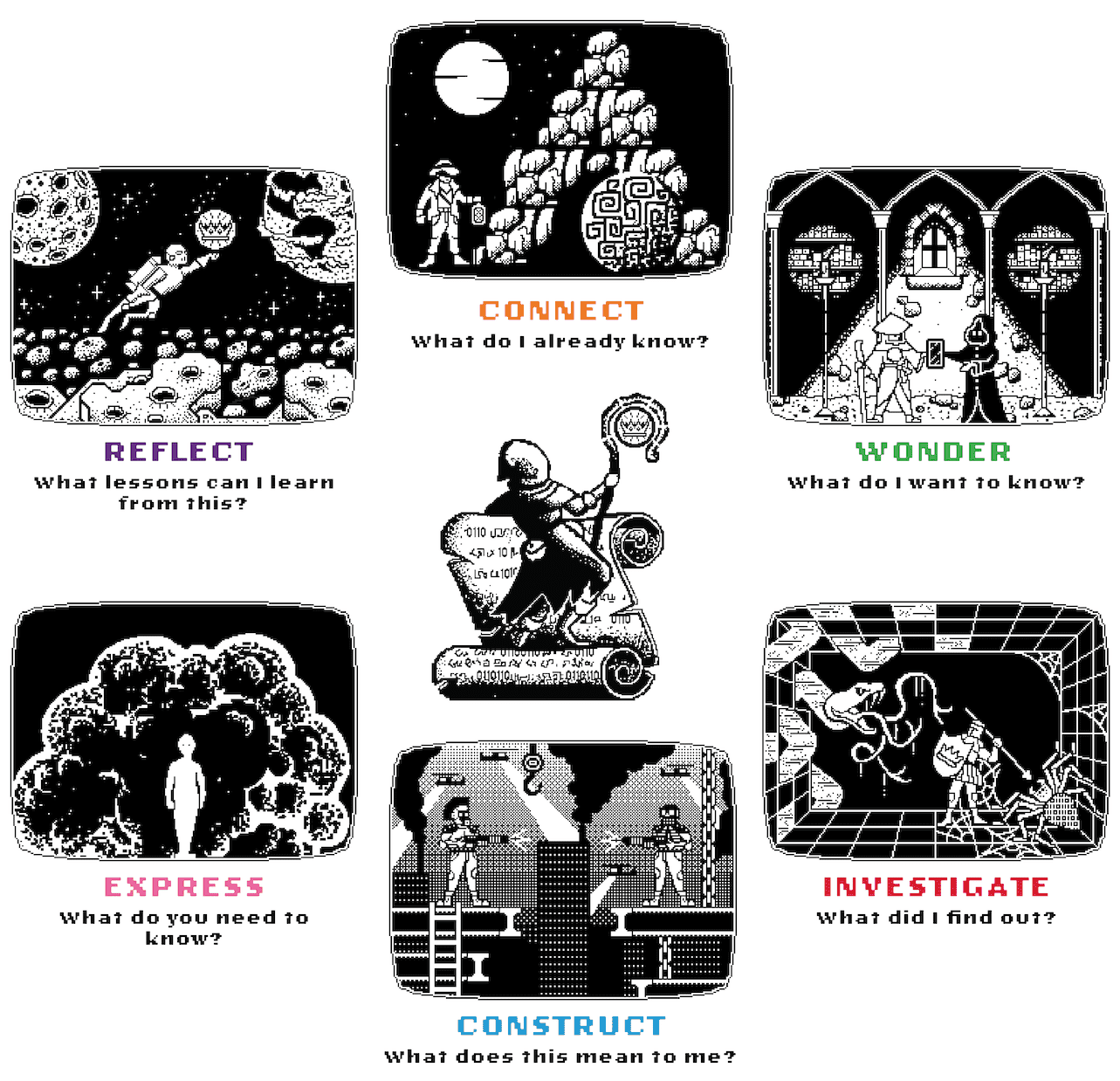

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

The Heroic Inquiry (2.1) icons are also available for individual download:

- 0. Central Heroic Inquirer (download PNG)

- 1. Connect (download PNG)

- 2. Wonder (download PNG)

- 3. Investigate (download PNG)

- 4. Construct (download PNG)

- 5. Express (download PNG)

- 6. Reflect (download PNG)

—

—

—

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

27th February 2025 at 3:25 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85660

27th February 2025 at 3:25 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85660Endorsement received from Dr David Loertscher, Professor at San Jose State University | School of Information.

25th February 2025 at 10:30 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85654

25th February 2025 at 10:30 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85654The stable release of the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 reboot of Heroic Inquiry (2.1) in Resources is now imminent.

Firstly, the stable release of the central Heroic Inquirer (2.1) has the Heroic Inquirer’s left hand reaching over the top of the scroll/ record, suggesting more active use of the scroll/ record to engage in the Heroic Inquiry process.

Secondly, the stable release Heroic Inquirer (2.1) has been incorporated into the stable release of Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short (below) and Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long. Furthermore, the stage colours are now FOSIL Standard Dark. The posters, cycles and icons will be uploaded to Resources shortly.

15th February 2025 at 12:27 pm in reply to: Session 3a: Ruth Maloney (Tonbridge Grammar School) #85570

15th February 2025 at 12:27 pm in reply to: Session 3a: Ruth Maloney (Tonbridge Grammar School) #85570Thank you for posting this, Ruth, which appears to be an encouraging development, and I have taken the liberty of adding your image to your post for ease of reference.

This is one of the frustrations that I had with the IB Diploma Programe (IBDP), and then the Middle Years Programme (IBMYP), before we left Oakham.

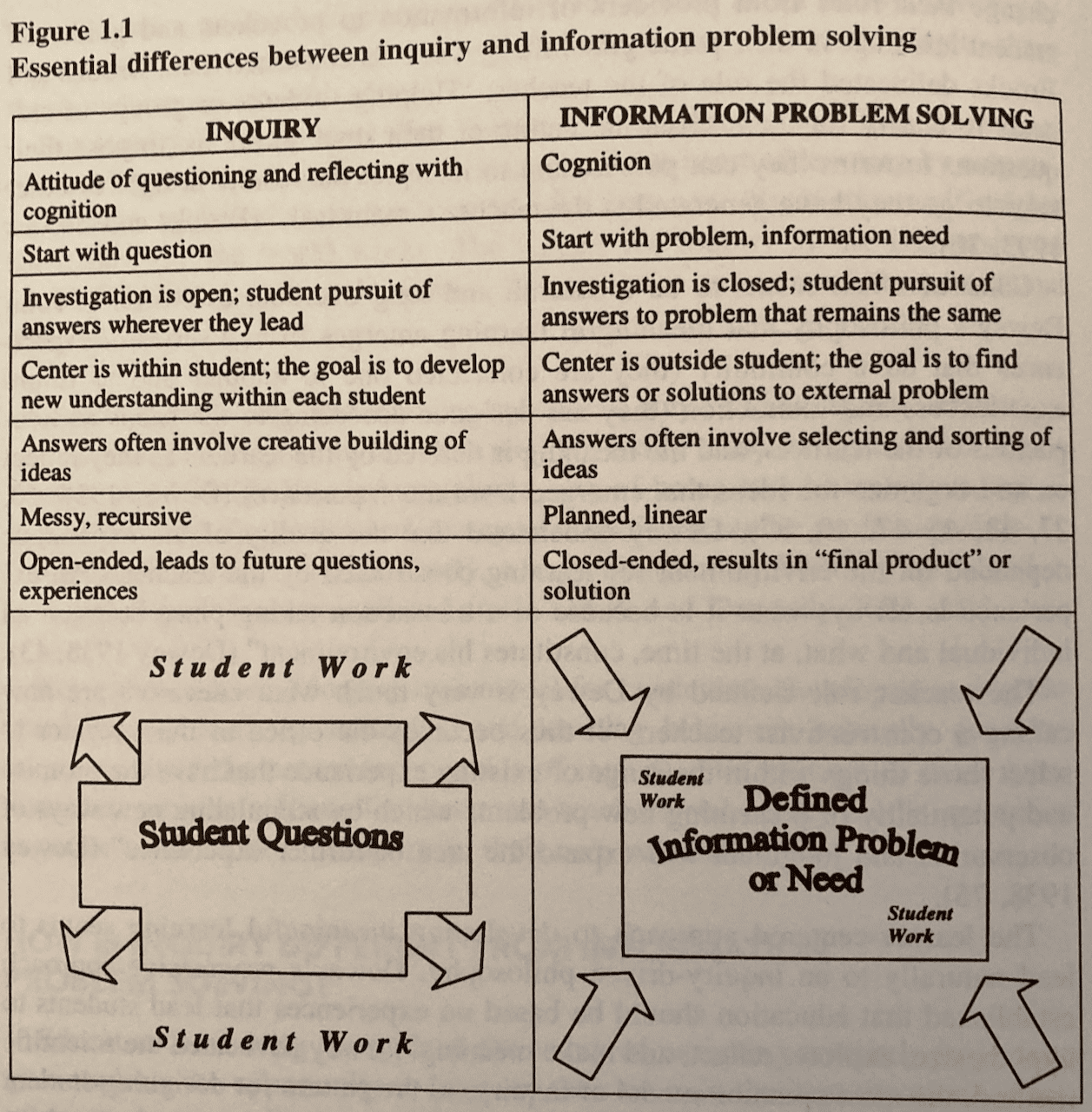

As Anthony Tilke (2011, p. 5) points out, “inquiry, as a curriculum stance, pervades all [IB] Programmes,” so why not (1) use a robust model of the inquiry process, and then (2) locate the desired inquiry skills within the appropriate stages of the inquiry process? Which is what Barbara did, and on of the main reasons why based FOSIL on her models and framework of skills – this makes the world of difference to both teaching the skills and learning with the skills.

Moreover, as the IB (2019, p. 9) points, “Libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin…and the librarian is responsible for energizing and maintaining the inquiry process. Ideally, the librarian is trained in many ways of creating conditions for inquiry within and beyond the classroom … Inquiry is more expansive than research, and facilitating it requires expertise beyond research methods (Callison, 2015 and Levitov, 2016).” It is, in my opinion, confusing and unhelpful to make this distinction so clearly in one place, and then then to blur that distinction elsewhere.

What transformed the IBDP Extended Essay (EE) for us at Oakham, which we had 13 years of experience with, for both teachers and students, was viewing and approaching the EE as an inquiry process rather than a research process. The main difference was that we moved almost immediately from requiring students to start with questions, which they then narrowly attempted to answer, to students starting with a topic that they then investigated/ researched, in order to formulate a question that emerged from their investigation/ research and the evidence that they had uncovered.

I would not hesitate to use FOSIL (or any other legitimate model of the inquiry process), in place of the Big6 (or any other research/ information problem solving model), even if, as you rightly rightly point out, it gets things the wrong way round, because it is an opportunity that the IB has given you to actually do things the right way round. Perhaps broader change is possible, and an opportunity exists for a revolutionary school to take the lead in this.

The choice of the Big6 as an example is an interesting, because it is an information problem solving process rather than an inquiry process – Barbara addressed this distinction in How is Inquiry Different From Information Problem Solving, in her chapter on Inquiry-Based Learning, in Curriculum Connections Through the Library (2003, pp. 4-6).

The differences are summarised in the following table (p. 6) – note that the starting question in inquiry is not the same as the final/ formal question that emerges from the investigation:

Also, like most/ all information problem solving/ research process models, it appears that the Big6 is no longer being actively developed and supported, and is/ was proprietary. This reflects the broader shift from research process models to inquiry process models – see, for example, the first (2002) and second (2015) editions of the IFLA School Library Guidelines – and means that it is unlikely that schools adopting it will be part of a vital, supportive community of inquiry/ practice.

References

- IBO. (2019). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organisation.

- Stripling, B. K., & Hughes-Hassell, S. (Eds.). (2003). Curriculum Connections Through the Library. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Tilke, A. (2011). The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program and the School Library: Inquiry-Based Education. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

12th February 2025 at 1:36 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85738Endorsements received from Dr Luisa Marquardt, Professor at Roma Tre University | Department of Education and Chair of the School Libraries Section | IFLA

—

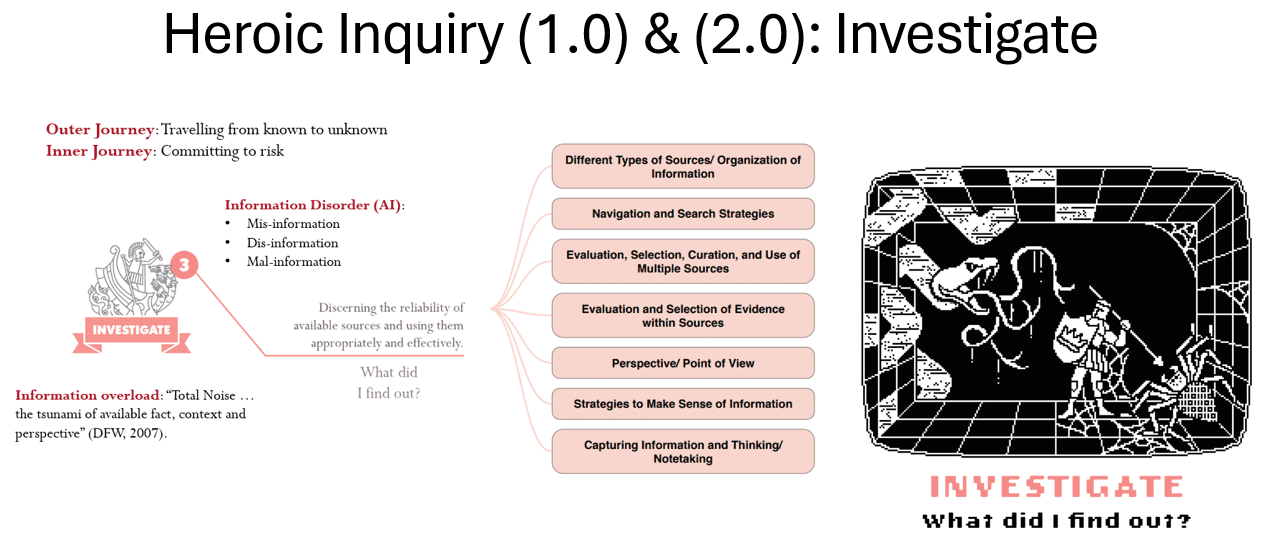

11th February 2025 at 3:01 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85528

11th February 2025 at 3:01 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85528I share the following for completeness of the proceedings, but please note that I am waiting for a minor adjustment to the stage colours, after which we will make the posters, stages and images available in Resources.

—

—

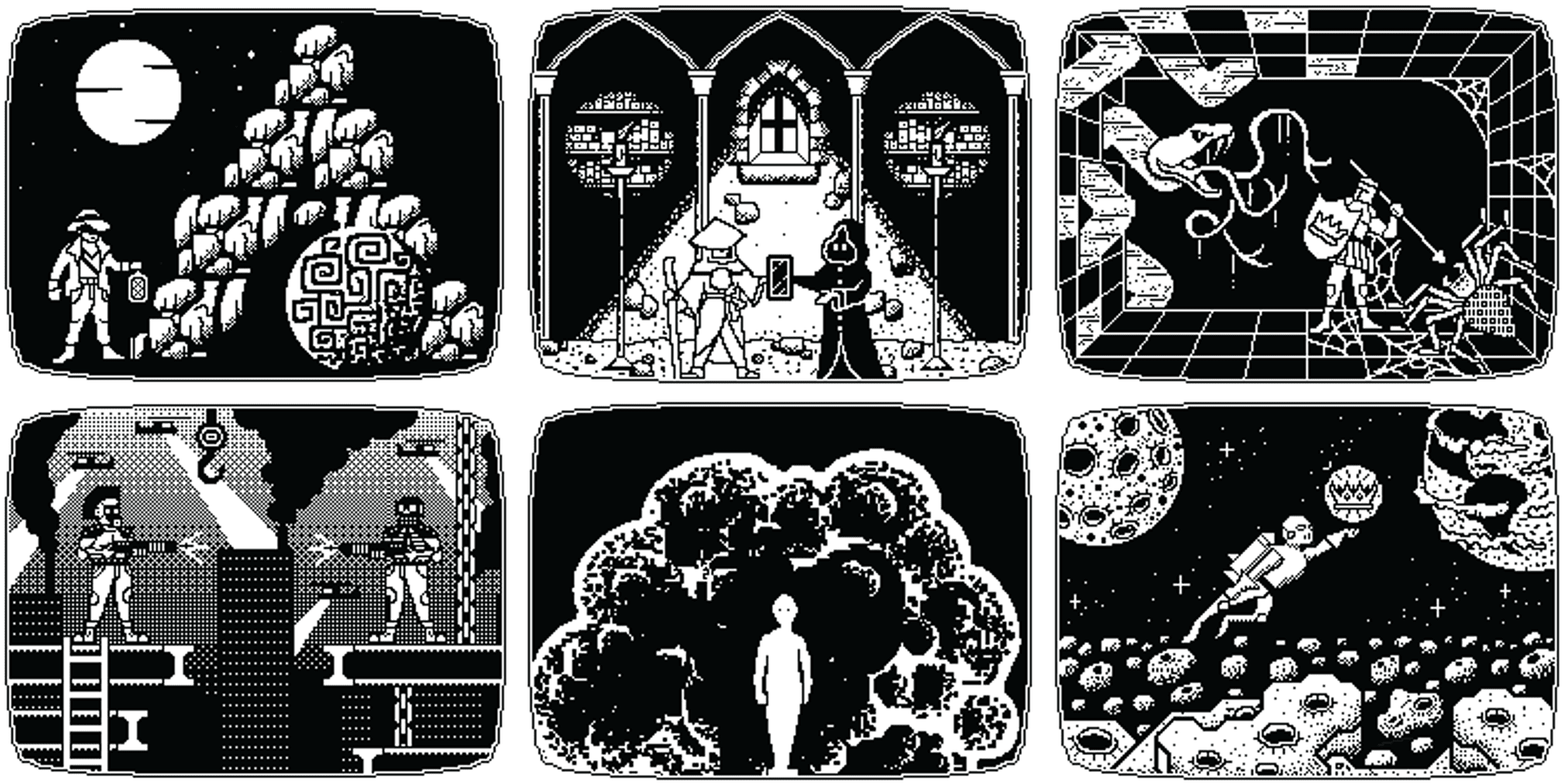

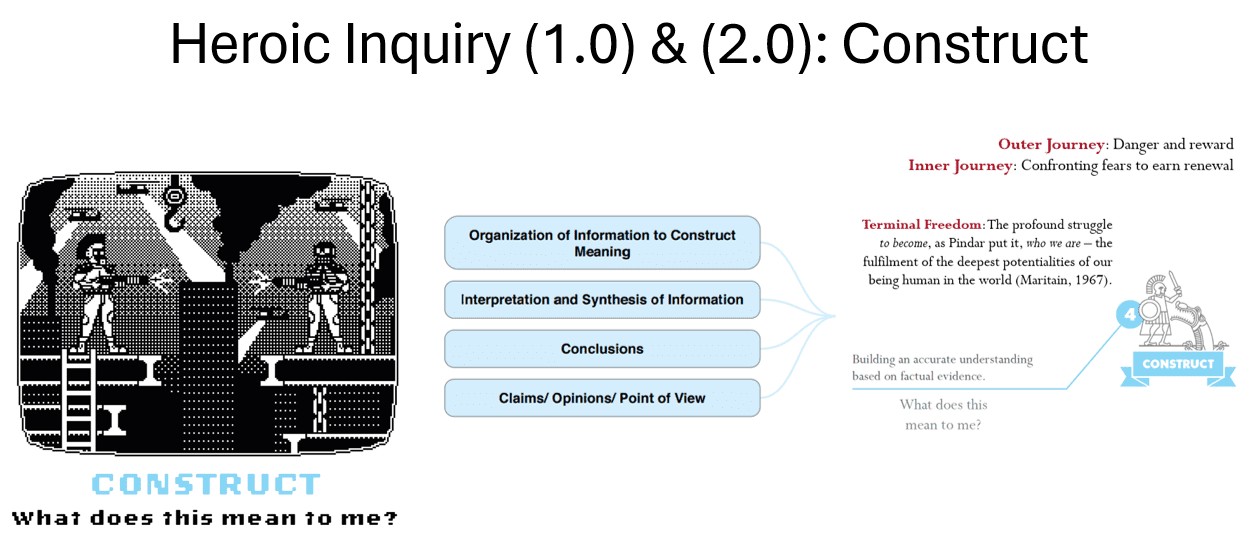

A reminder of of what is going on in Investigate and Construct.

11th February 2025 at 12:22 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85523

11th February 2025 at 12:22 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85523The work with Hugh Rose on the Creative Commons (CC) reboot of Heroic Inquiry will require the most time to discuss, but I don’t want to delay making the link to proceedings live. Therefore, and for now, I will make the following observations:

- The ‘classical’ version of Heroic Inquiry (1.0) was produced in collaboration with Hugh Rose in 2021 while he was working at Blanchelande College under the previous Principal, whose influence on the images was strongly felt. This is appropriate, given the centuries-long educational tradition in Guernsey that Blanchelande is rooted in.

- Because this iconography is so closely associated with Blanchelande, opportunities to share our unfolding understanding of the embodiment of the inquiry stance and process in the Heroic Inquirer and through the Heroic Inquiry journey were constrained. Moreover, as the current Principal, Alexa Yeoman, noted in her address, being rooted in this rich tradition does not trap us in the past, given Blanchelande’s commitment to providing an outstanding contemporary liberal education, of which inquiry is a distinguishing feature. This forward-looking educational stance enables us to equip our students for their futures as engaged and empowered independent learners and active citizens, as our Director of Studies, Jane Grange, noted in her address.

- Growing interest in Heroic Inquiry, combined with a growing need to reconceptualise Heroic Inquiry in contemporary terms that spoke more directly to the reality our students need to deal with, created the conditions for the CC reboot of Heroic Inquiry in 2024-5.

- This posed a number of challenges, not least of which were that Hugh no longer worked at Blanchelande, I had a limited budget for FOSIL-related development and we had a very tight deadline if we were to share the CC reboot during the FOSIL Symposium. I am indebted to our then-Acting Principal, Mike Elward, who immediately saw the importance and value of this work, as well as freely sharing it under a CC licence, and to our Bursar, Mark Lewis, for approving an out-of-budget expense. My meetings with Hugh were limited to evenings and weekends, and many emails.

- This led to technical difficulties that will become apparent. In order to make the reboot as inclusive and diverse as possible within the constraints above, and without resorting to forced stereotypes, we decided to approach the Heroic Inquiry stages in the style of a video game (although there are also cinematic references), in which character creation and identification is natural. While we did not have time to investigate deeply, a cursory investigation confirmed that this combination of video game style with cinematic references appealed equally to boys and girls. The settings of the stages gave us further opportunities for inclusion and diversity. The pixelated style created exciting possibilities, but also imposed technical limitations that I do not fully understand – especially considering that we deliberately chose not to use colour (except for the stage names, which will print fine without) – but can appreciate.

- Additionally, we used the following for racial/ethnic reference, although this aspect was even more difficult to respectfully address: National Center for Education and Statistics, Definitions for New Race and Ethnicity Categories (2025).

- While we did not hold any formal consultations during the design process, we did not work in isolation, and sought and acted on feedback from a relatively diverse audience, which included both boys and girls of school-going age, and from different nationalities. Hugh shared the following thoughts with me following his presentation: “I encourage educators to look at this poster as a storytelling tool. It is up to them to tell the story and bring it alive for their students. The images have been carefully designed to allow the use of various pronouns and indeed cultural references. I hope everyone has fun creating their own epic stories with the framework we have created!“

- An unexpected budgetary difficulty that we ran into was that I had not accounted for the central Heroic Inquirer, so Jenny and are the proud ‘owners’ of this image!

We are proud to share the final design under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, and encourage colleagues to adopt or adapt as needed, and to share their experiences. I will reflect on the stages and images from my perspective in due course.

11th February 2025 at 11:12 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85522Every inquiry, whether formal or informal, is a heroic journey.

Broadly, inquiry is a movement – intellectual,certainly, but also, and equally important, physical, emotional and social – from the comfort of the known into the discomfort of the unknown, there to wrestle knowledge from information and understanding from knowledge. There lurks real danger here, for being even somewhat misguided can lead far astray, and so discerning those who would help from those who would hinder, or even harm, is vital. From this now-enlightened place to return, enlivened and alive to possibilities heretofore unimagined. And so to set off again.

This heroic journey of inquiry is the story of those who have stretched the boundaries of human knowledge and understanding in one or more of the fields of study in which they laboured, and those who labour there still. It is this unfolding story that we are inviting our students to identify with and, in learning to stretch the boundaries of their own knowledge and understanding, add their voice to and so find their place in.

11th February 2025 at 10:00 am in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85521Endorsing the Institute

The foundation of the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry – the purpose of which is to initiate and support efforts, formal and informal, that foster the development of school-age children as engaged and empowered inquirers, which both enables them to fulfil the deepest potentialities of their being human in the world, and strengthens the liberal-democratic fabric of society – is clearly necessary and urgent.

This is evident from the extraordinary interest in and contribution to the FOSIL Symposium, which was not limited in focus to FOSIL.

It is also evident in the heartening endorsements of the Institute that I have already received, which I include below in chronological order.

—

Dr Barbara Stripling, Professor Emerita at Syracuse University | School of Information Studies first helped me to set this work in motion more than a year ago (23 January 2024):

I wholeheartedly support the establishment of an institute to support the school library field in developing inquiry-based libraries and schools. The reasons for creating a culture of inquiry in every school are numerous, but they all revolve around the essential core – the empowerment of young people to follow their own sense of wonder, navigate the world, and pursue their own paths of learning.

School librarians across the world are grappling with the complexities of transforming their libraries and schools into centers of inquiry. An online institute would provide open access to relevant research, practical strategies, success stories, adaptable models and frameworks, professional development, and a network of colleagues who are engaged in this important work. An online institute would also provide an incubator for new ideas and planning for the future.

I would be honored to collaborate with Darryl Toerien in developing and contributing to an inquiry institute.

Pending Endorsements

- Dr David Loertscher, Professor at San Jose State University | School of Information

- Dr Luisa Marquardt, Professor at Roma Tre University | Department of Education Science and Chair of the School Libraries Section | IFLA

-

AuthorPosts