Darryl Toerien

Active 2 days, 13 hours agoRole: Head of Inquiry-Based Learning

Town/City: Guernsey

Country: United Kingdom

Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

24th June 2025 at 1:08 pm in reply to: Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86956

On Thursday, 19 June, we held our third annual Year 9 Signature Work Inquiry Celebration.

As I explained to parents, the Signature Work poster is similar to an article’s Abstract, in that it both summarises a larger body of work and reflects a learning journey that is itself embodied and situated.

This year I gave parents an overview of what this learning journey entailed: deeply thoughtful reading into a personally-chosen topic related to the theme; a 1-minute speech in English; a 2-minute speech in Geography; a 750-word essay plan overview; an essay plan; a handwritten draft essay; a typed re-draft; a typed re-draft in response to feedback, and; cue cards for the 5-minute speech in English.

As is customary, one student was chosen to represent Year 9 with their speech, and this year we could not be prouder of Flo.

24th June 2025 at 11:42 am in reply to: Year 2 (Grade 1) Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86951

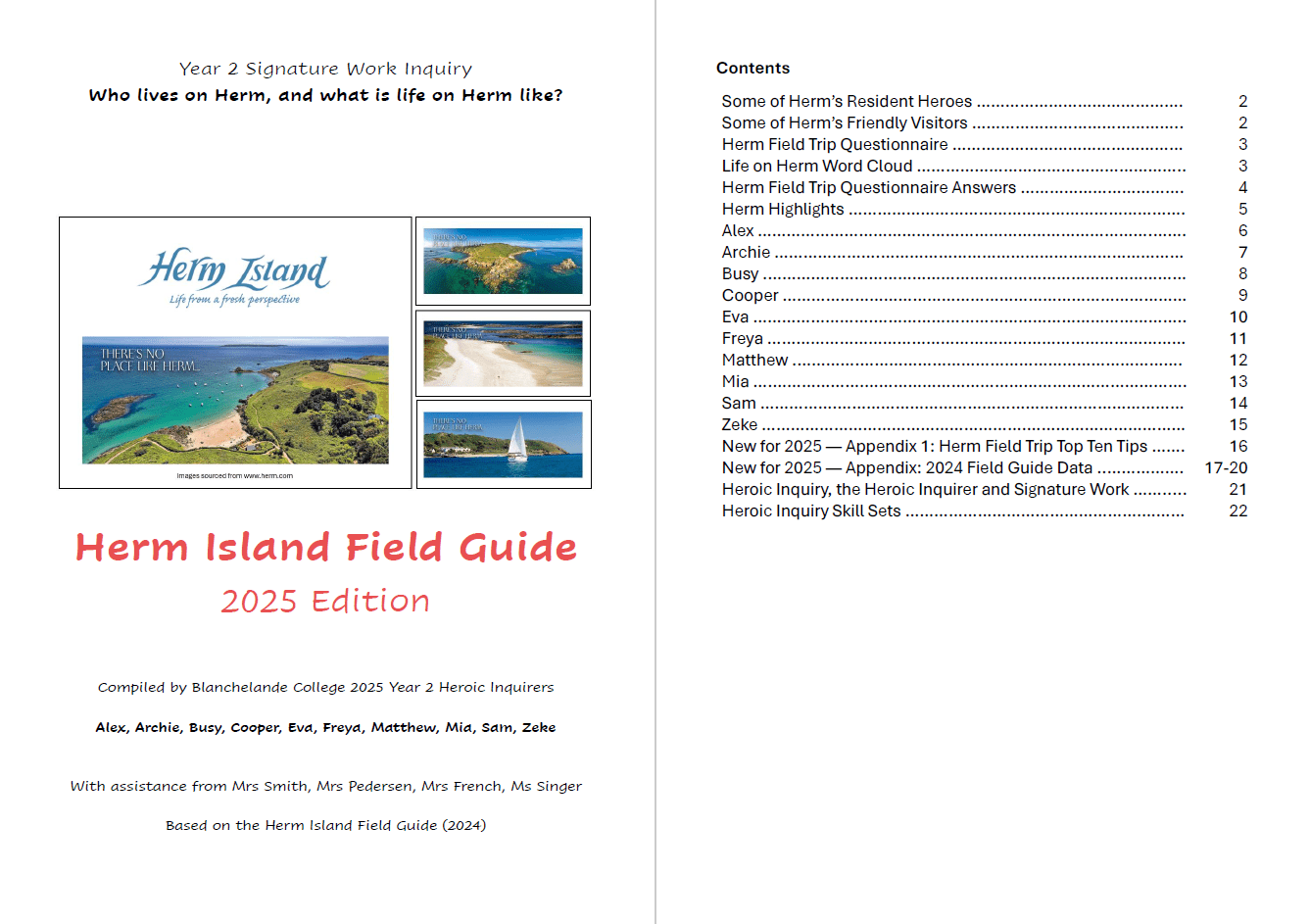

24th June 2025 at 11:42 am in reply to: Year 2 (Grade 1) Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #86951On Wednesday, 18 June, we held our second annual Year 2 Signature Work Inquiry Celebration.

Herm is a very special place, made more so by the very special people who live and work there, and the purpose of the Year 2 Signature Work Inquiry is to build knowledge and understanding of what life on Herm is like, for both residents and visitors.

We were delighted to be joined by Shaun McDonald, General Manager of The White House Hotel, and Alison Veitch, Head Chef.

I realise now, to my shame, that I did not share highlights from last year’s Field Guide; however, I share highlights from this year’s Field Guide instead. The Field Guide is published by the Library and presented to staff and students who took part in the Field Trip, as well as the residents who we met.

Thanks, Ruth and Elizabeth.

I’ve just read a very interesting article by Peter Michael Gratton, called The Banality of Complicity: Arendt’s Guide to Moral Resistance in the Age of Trump, in which he discusses Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963) and subsequent lecture in 1964, Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship.

Gratton observes that Arendt’s lecture “is uncanny in precisely identifying the psychological and moral patterns of capitulation [to] and cooperation [with authoritarian systems] we see playing out today,” and it struck me that there are parallels with the uncritical and wholesale embrace of AI. For example:

Equally troubling [to the alarming speed with which moral standards can be inverted overnight] is Arendt’s insight into how readily people surrender individual judgment to systems. … The lecture isn’t [however] some grandstanding harangue about the need for heroism. Instead, she makes clear that resistance begins not with heroic action but with the simple refusal to participate in the regime and its lies, as well as the comfortable self-deceptions that make complicity possible. … Having knocked down the last of the excuses of the complicit—what else was I to do?—Arendt can move to the central claim of the lecture: that “obedience” always amounts to support, no matter what we tell ourselves to sleep at night. … What makes Arendt’s [lecture] so profound is that she locates resistance not in grand gestures requiring extraordinary heroism, but in preserving one’s capacity to think independently and refuse complicity in evil even when everyone else has capitulated. We cannot control the circumstances we inherit—so many never asked for this—but we always retain the power to withhold our support from systems that violate human dignity. And in that vital first act of defiance lies the seeds for resisting the reality in which we find ourselves today.

Edit:

I would say that reality is what we have to deal with, and that success is dealing with reality, which is not to say that dealing with reality doesn’t alter the reality we have to deal with.

From the conclusion to my article, “the revolution, and the unfolding resistance that must now precede it, will not be televised brothers and sisters, because the revolution will be live.”

11th March 2025 at 3:05 pm in reply to: Year 9 (Grade 8) Interdisciplinary Signature Work Inquiry @ Blanchelande College #85777In Defence of the Essay

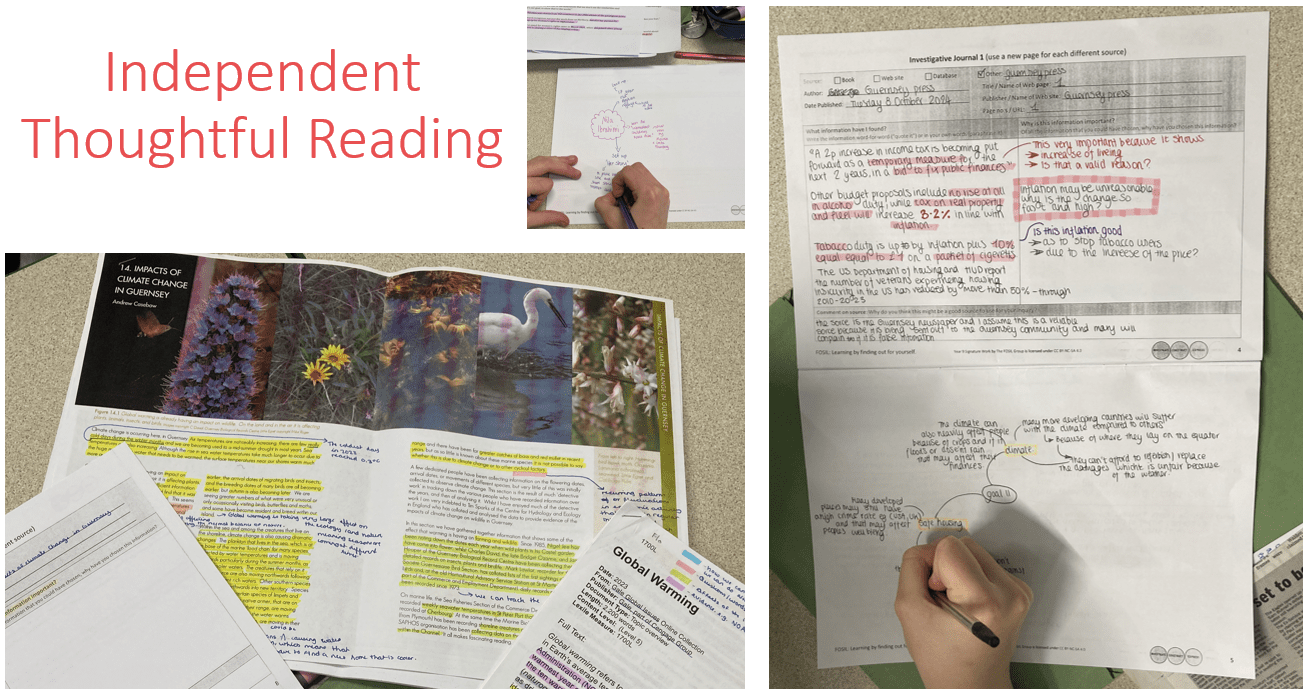

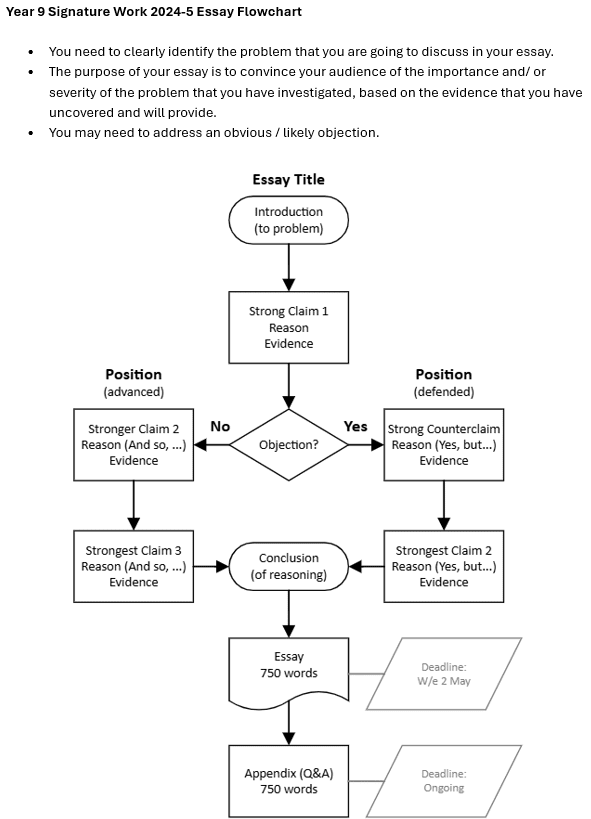

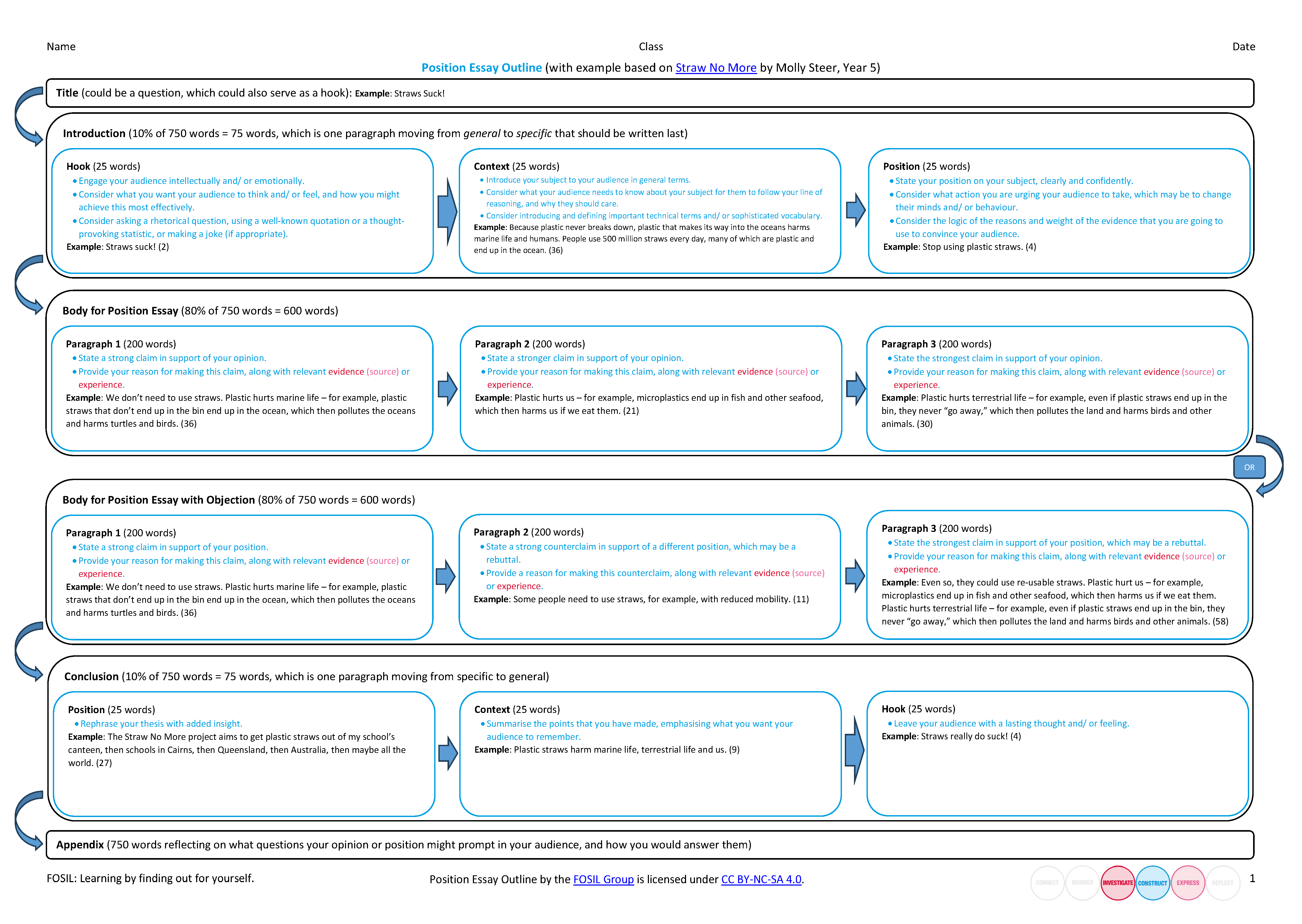

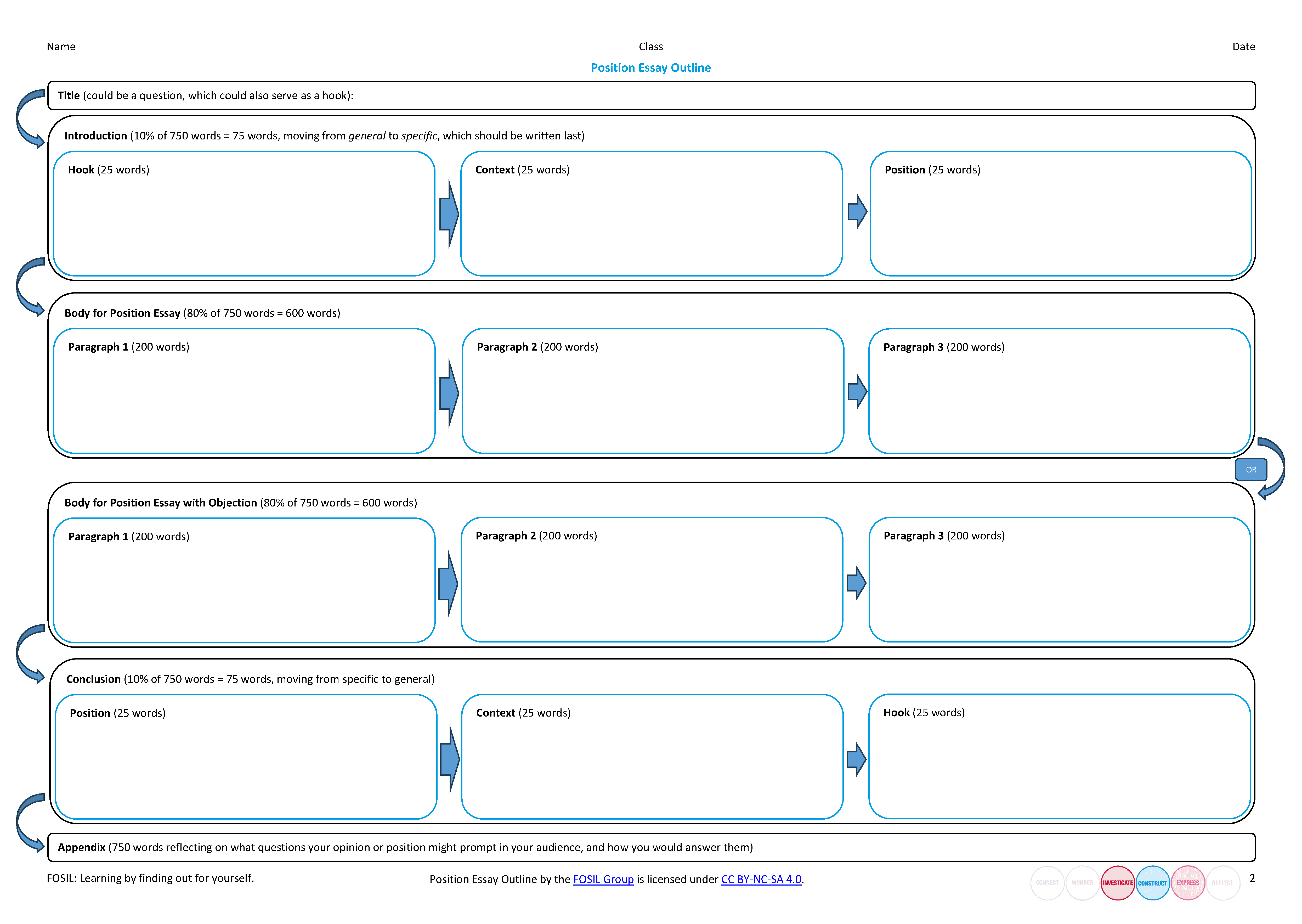

We have reached the point in the Year 9 Signature Work inquiry where we shift our focus from thoughtful reading to thoughtful writing, which will take the form of a 750-word essay in which students will (a) clearly identify and define the problem that they intend to discuss, and (b) attempt to convince their audience of the importance and/ or severity of the problem based on evidence that they uncovered during their investigation and will present in their essay.

Why, one might ask, as some do, teach students to write an essay if AI can write a better essay? Now while there may be more to this question than at first appears, it is, as asked, a question that demands an answer.

The simple answer is that we are not, in fact, teaching students how to write an essay, but to think, with the essay in this case being a tool to think with, and a particularly powerful one at that.

This distinction may seem pedantic, but is, in fact, profound, especially as AI intrudes its way into every aspect of our lives.

As Christopher Newfield (2025) writes:

My root worry about AI has always been that while it was making machine learning better, it was also making human learning worse. I am not alone in this. Teachers, who are responsible for helping students think, were increasingly furious about what AI was doing to the student brain.

A week before ChatGPT was released, Jane Rosenzweig, director of Harvard College’s Writing Center, made what should be an obvious point: “Writing—in the classroom, in your journal, in a memo at work—is a way of bringing order to our thinking or of breaking apart that order as we challenge our ideas. If a machine is doing the writing, then we are not doing the thinking.”

…

I draw several conclusions here.

…

Second, the high-value economic benefits of AI require fully empowered human use of AI as tools. Benefits will depend on society devoting much more effort than it now does to the expansion of human capabilities, rather than seeing technology as rescuing society from the self-inflicted enshittification of its human systems. The rigourous teaching of writing and thinking is more essential than ever.

Students have now spent a term investigating a SDG-related problem that they have identified and defined, which is a distinguishing feature of Signature Work inquiry. I have been deeply impressed by how purposefully many students in this cohort have used their Investigative Journals as tools to think with.

The next step, however, is daunting, even for university-level students, which is why there is real value in helping students with this in school. As Newfield (cited above) explains:

I learned during my decades of teaching university-level writing that students can mostly find a general topic that interests them. But they struggle with the next question: what do you want to say about your topic? What’s your thesis, your claim, about it? This stage turns out to be very hard, and the simple reason is that it’s where independent thinking has to happen. It’s where the student diverges, however slightly, from what has already been said. If a GPT product is available, the student—or anyone, myself included—will be tempted to use it to skip this thinking stage.

To help students with this last year, I developed the Opinion Essay and Position Essay flowchart and graphic organiser (see post #83043 above). This year I have simplified the flowchart and graphic organiser slightly (see below), and also added an example to the graphic organiser based on the Straw No More presentation by Molly Steer at TEDxJCUCairns (2017), which we looked at in class.

This is the critical moment, as Newfield highlights above, when students become more fully themselves, or less, as they face twofold temptation of letting the machine [and its programmers] think for them and speak for them–as Janet Salmons (2025, emphasis added) warns, “the implicit message [of AI offering to (re)write for you] is less than subtle: use the words we tell you to use, in the style we tell you to use, to say what we tell you to say, in the voice we tell you to use,” which is bringing about a “‘flattening’ of contemporary writing.” This is when I must trust that I have sufficiently “encouraged [my] students to engage in the process of acquiring knowledge, which is a very difficult process, [without which] all you get is memorisation and reproduction in tests” (Young, 2022), or in this case, copy & paste. This encouragement to engage–to Connect–takes time and energy, to be sure, but time and energy well spent on enabling my students to develop as engaged and empowered inquirers, increasingly willing and able to learn for themselves.

My confidence is high.

References

- Newfield, C. (2025, March 4). The Fight About AI. Retrieved from Independent Social Science Foundation: https://isrf.org/blog/the-fight-about-ai

- Salmons, J. (2025, January 28). Finding Your Voice in a Ventriloquist’s World – AI and Writing. Retrieved from The Scholarly Kitchen: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2025/01/28/guest-post-finding-your-voice-in-a-ventriloquists-world-ai-and-writing/

- Young, M. (2022, September 21). What we’ve got wrong about knowledge & curriculum. (G. Duoblys, Interviewer) Tes Magazine.

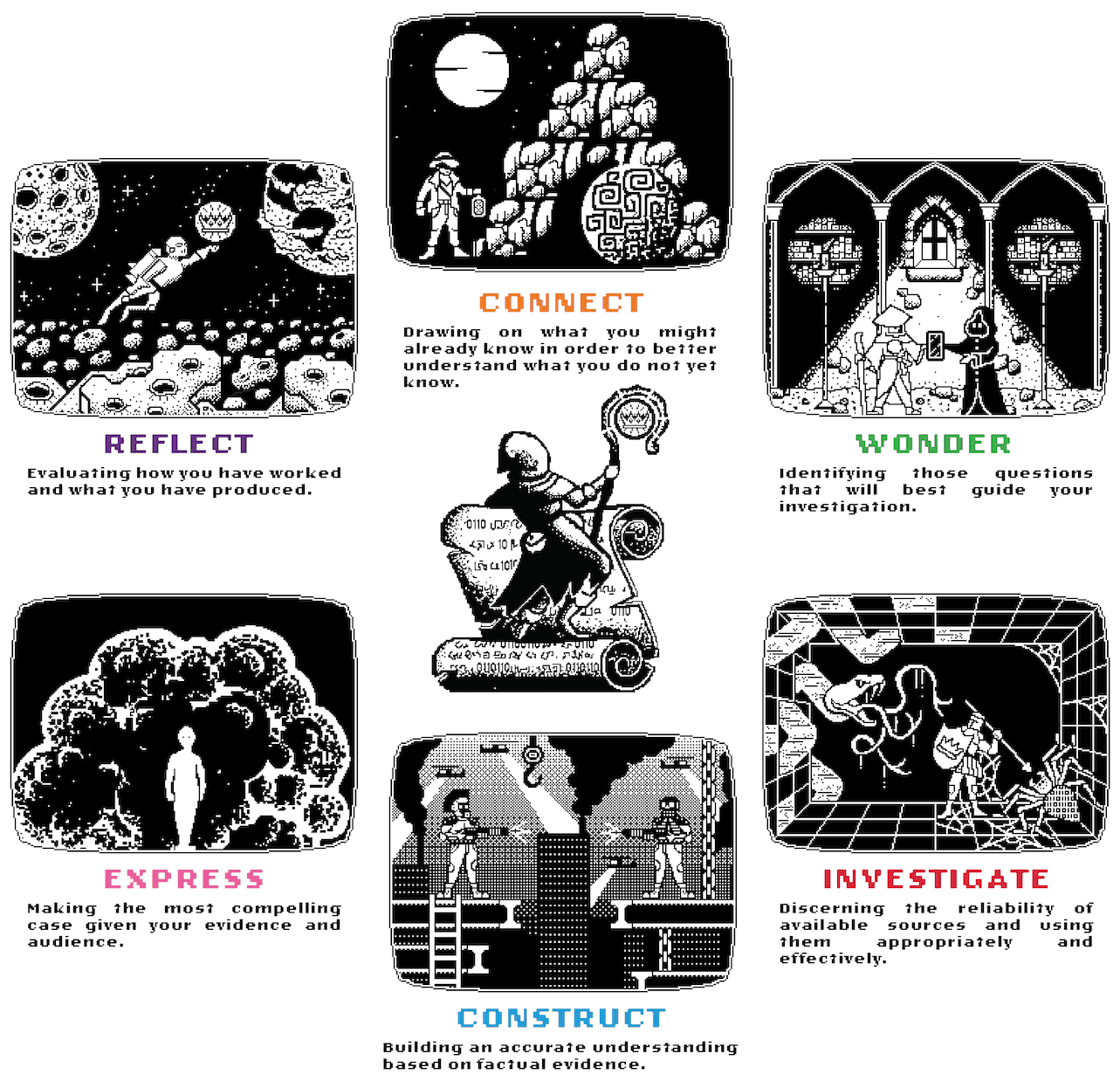

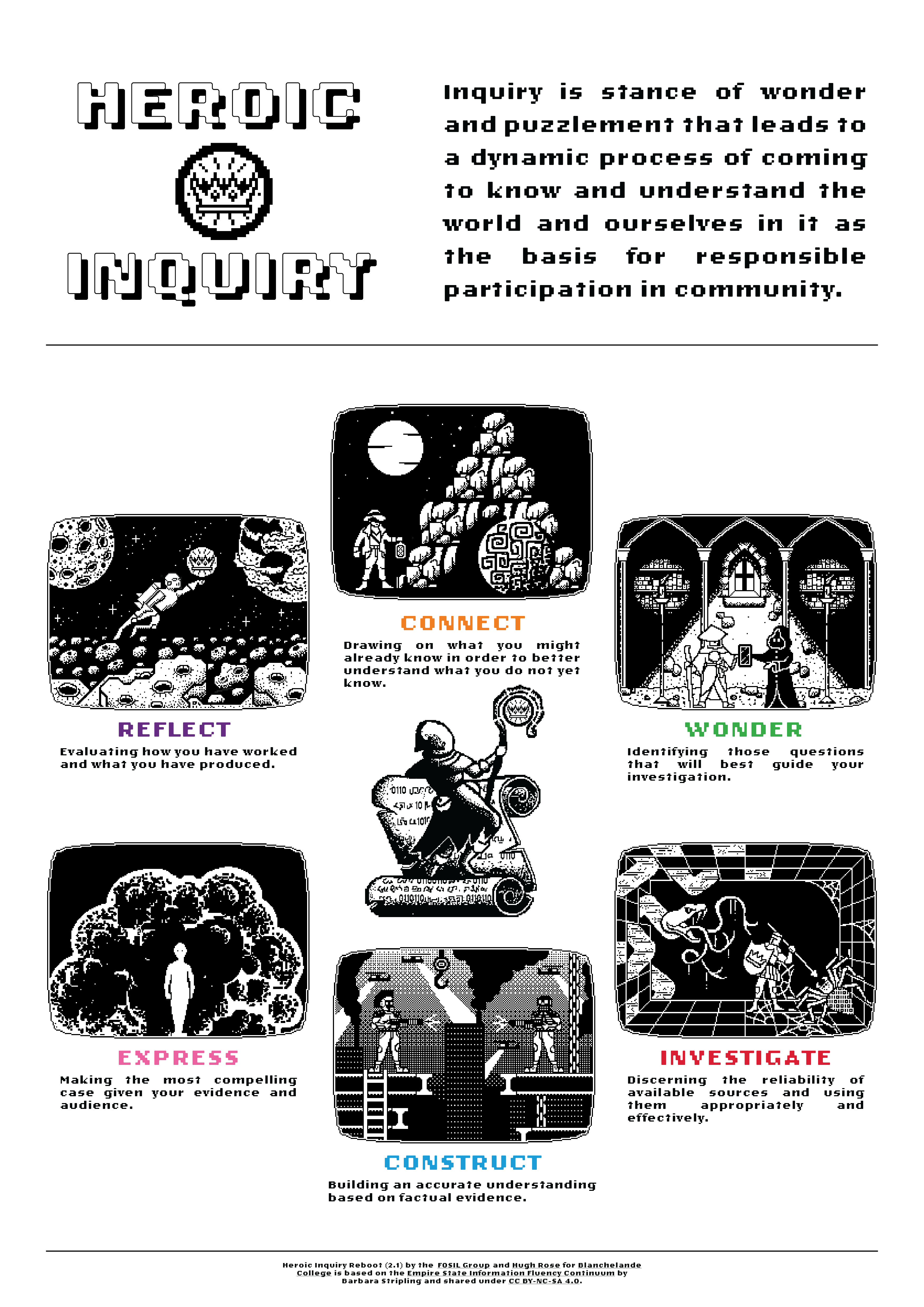

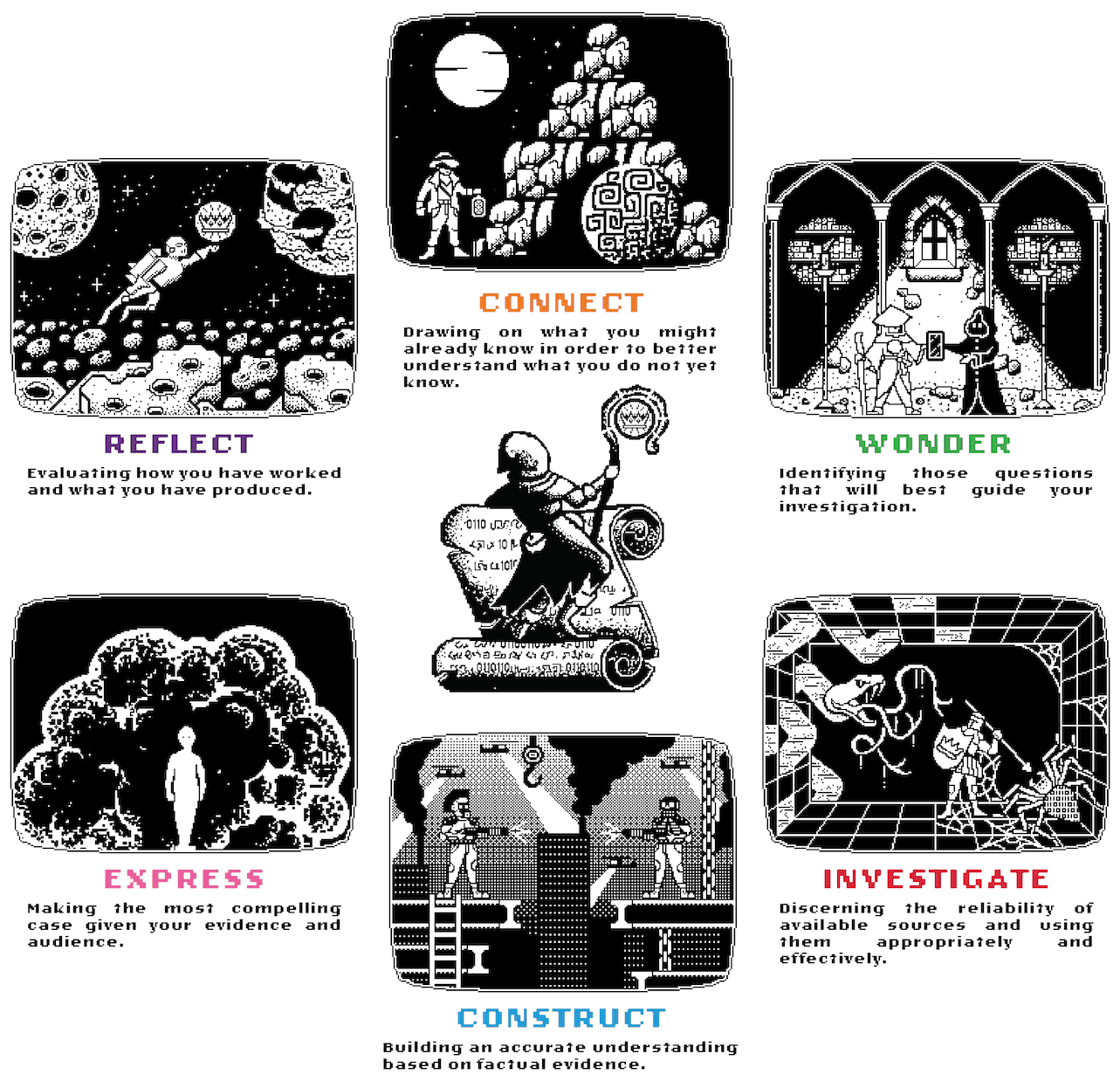

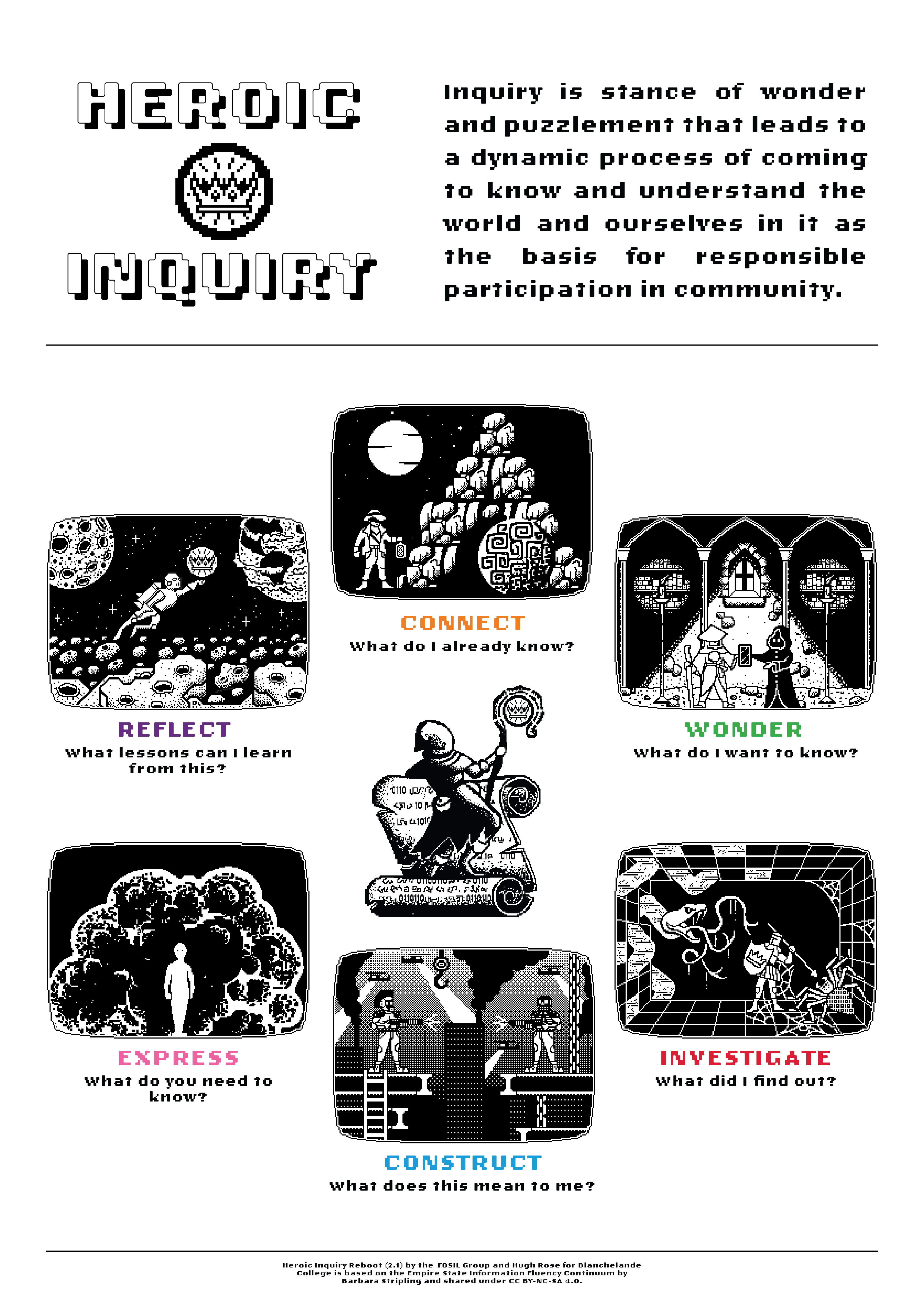

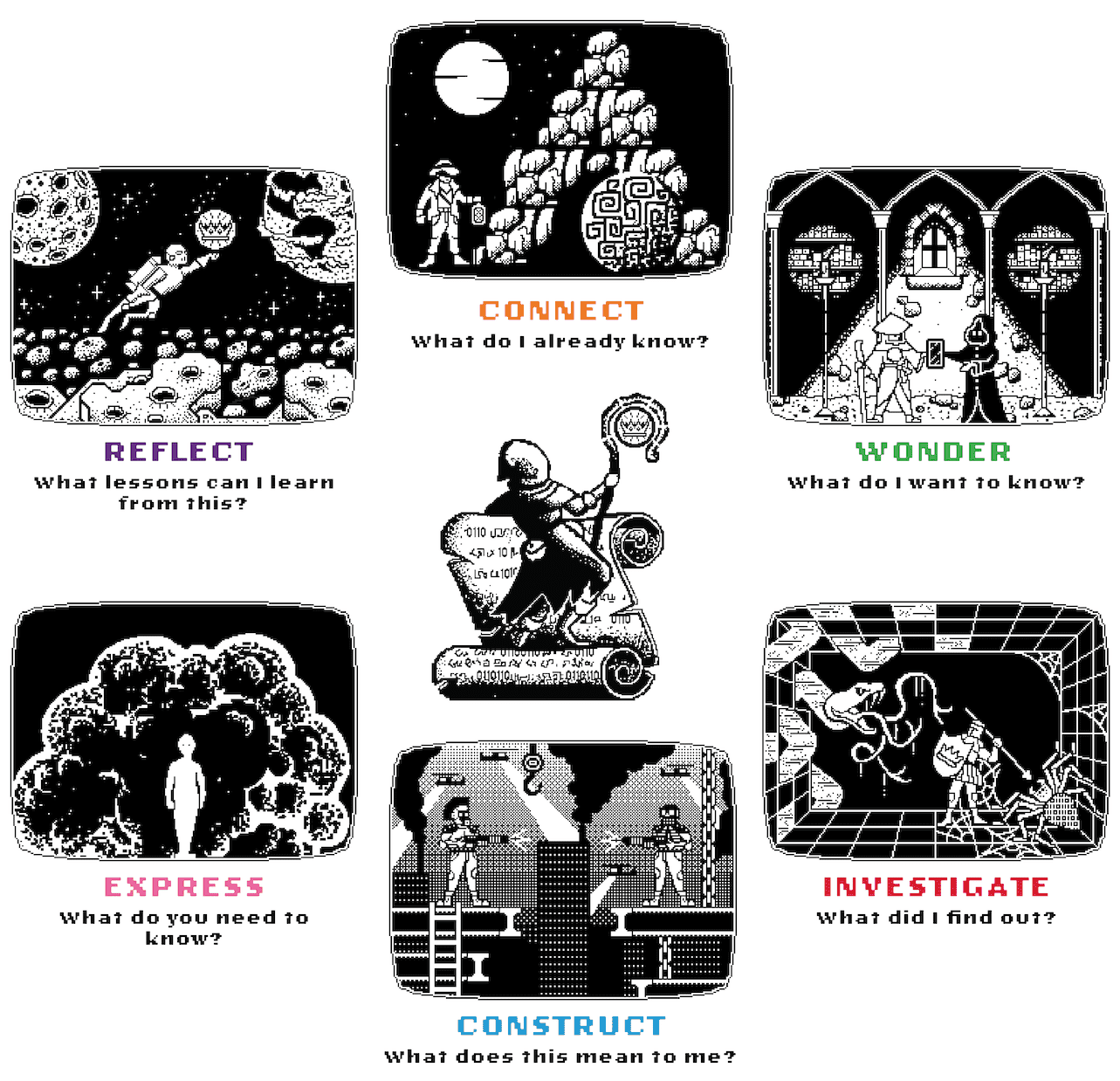

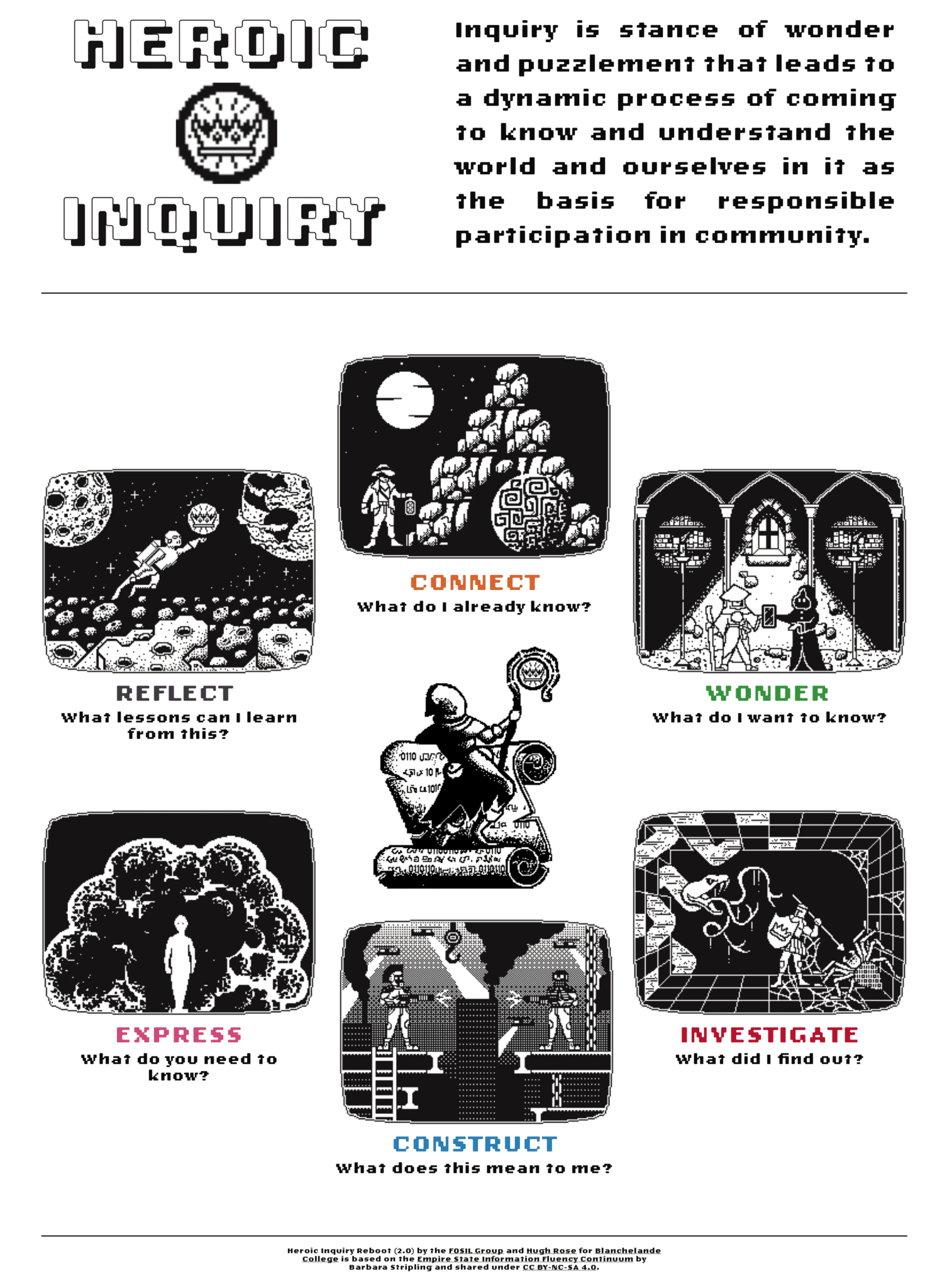

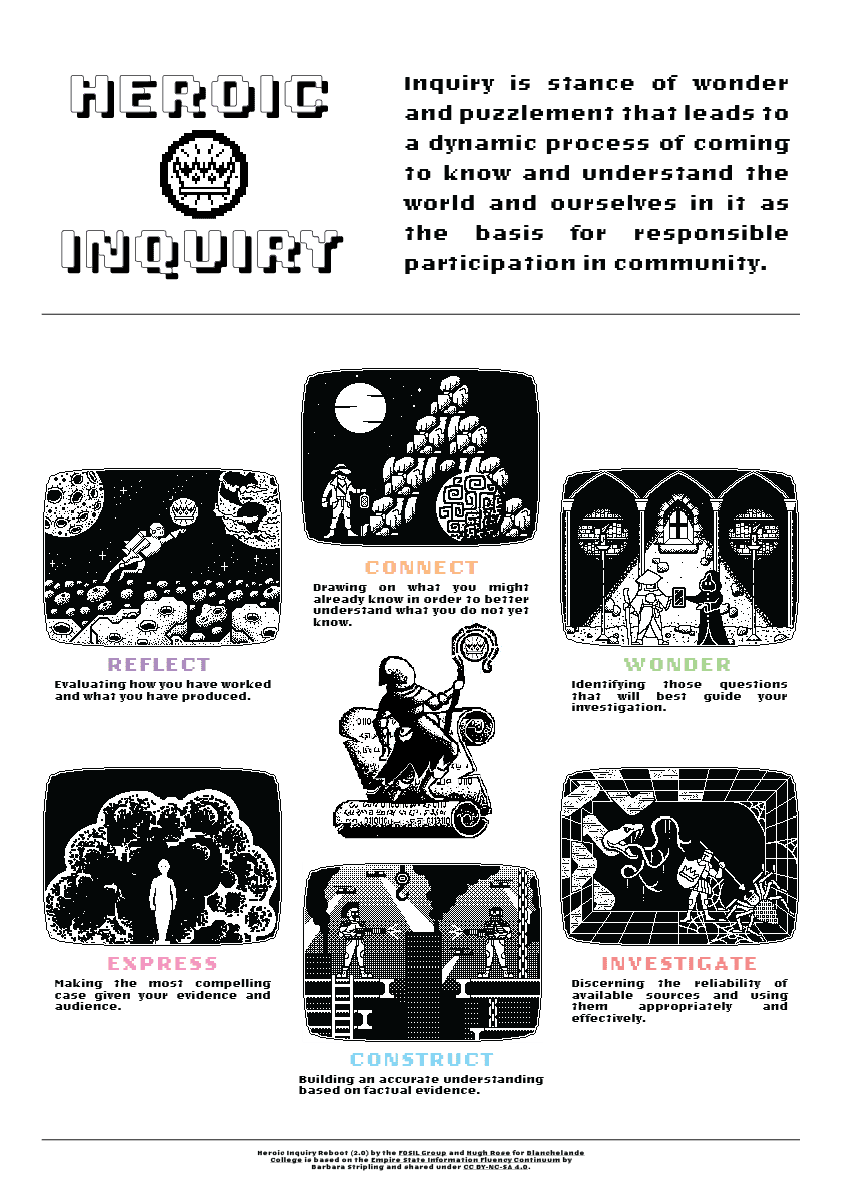

28th February 2025 at 10:35 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85696The CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 stable release of Heroic Inquiry (2.1) is now available for download:

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

- Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

The Heroic Inquiry (2.1) icons are also available for individual download:

- 0. Central Heroic Inquirer (download PNG)

- 1. Connect (download PNG)

- 2. Wonder (download PNG)

- 3. Investigate (download PNG)

- 4. Construct (download PNG)

- 5. Express (download PNG)

- 6. Reflect (download PNG)

—

—

—

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Poster (download PDF or PNG)

—

Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short stage descriptions | Cycle (download PNG)

27th February 2025 at 3:25 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85660

27th February 2025 at 3:25 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85660Endorsement received from Dr David Loertscher, Professor at San Jose State University | School of Information.

25th February 2025 at 10:30 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85654

25th February 2025 at 10:30 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85654The stable release of the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 reboot of Heroic Inquiry (2.1) in Resources is now imminent.

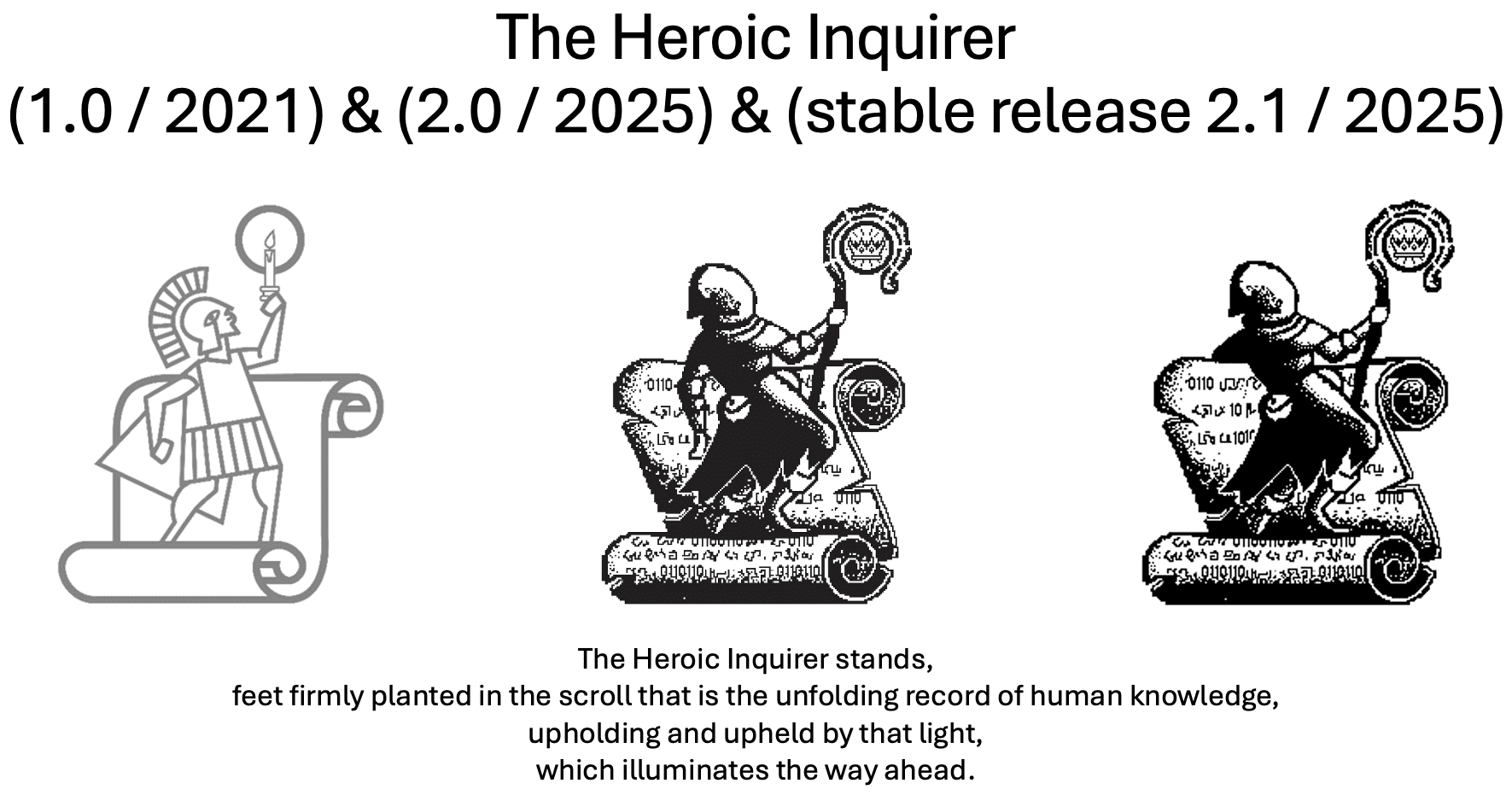

Firstly, the stable release of the central Heroic Inquirer (2.1) has the Heroic Inquirer’s left hand reaching over the top of the scroll/ record, suggesting more active use of the scroll/ record to engage in the Heroic Inquiry process.

Secondly, the stable release Heroic Inquirer (2.1) has been incorporated into the stable release of Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Short (below) and Heroic Inquiry (2.1) Long. Furthermore, the stage colours are now FOSIL Standard Dark. The posters, cycles and icons will be uploaded to Resources shortly.

15th February 2025 at 12:27 pm in reply to: Session 3a: Ruth Maloney (Tonbridge Grammar School) #85570

15th February 2025 at 12:27 pm in reply to: Session 3a: Ruth Maloney (Tonbridge Grammar School) #85570Thank you for posting this, Ruth, which appears to be an encouraging development, and I have taken the liberty of adding your image to your post for ease of reference.

This is one of the frustrations that I had with the IB Diploma Programe (IBDP), and then the Middle Years Programme (IBMYP), before we left Oakham.

As Anthony Tilke (2011, p. 5) points out, “inquiry, as a curriculum stance, pervades all [IB] Programmes,” so why not (1) use a robust model of the inquiry process, and then (2) locate the desired inquiry skills within the appropriate stages of the inquiry process? Which is what Barbara did, and on of the main reasons why based FOSIL on her models and framework of skills – this makes the world of difference to both teaching the skills and learning with the skills.

Moreover, as the IB (2019, p. 9) points, “Libraries are where most forms of inquiry, not just academic ones, begin…and the librarian is responsible for energizing and maintaining the inquiry process. Ideally, the librarian is trained in many ways of creating conditions for inquiry within and beyond the classroom … Inquiry is more expansive than research, and facilitating it requires expertise beyond research methods (Callison, 2015 and Levitov, 2016).” It is, in my opinion, confusing and unhelpful to make this distinction so clearly in one place, and then then to blur that distinction elsewhere.

What transformed the IBDP Extended Essay (EE) for us at Oakham, which we had 13 years of experience with, for both teachers and students, was viewing and approaching the EE as an inquiry process rather than a research process. The main difference was that we moved almost immediately from requiring students to start with questions, which they then narrowly attempted to answer, to students starting with a topic that they then investigated/ researched, in order to formulate a question that emerged from their investigation/ research and the evidence that they had uncovered.

I would not hesitate to use FOSIL (or any other legitimate model of the inquiry process), in place of the Big6 (or any other research/ information problem solving model), even if, as you rightly rightly point out, it gets things the wrong way round, because it is an opportunity that the IB has given you to actually do things the right way round. Perhaps broader change is possible, and an opportunity exists for a revolutionary school to take the lead in this.

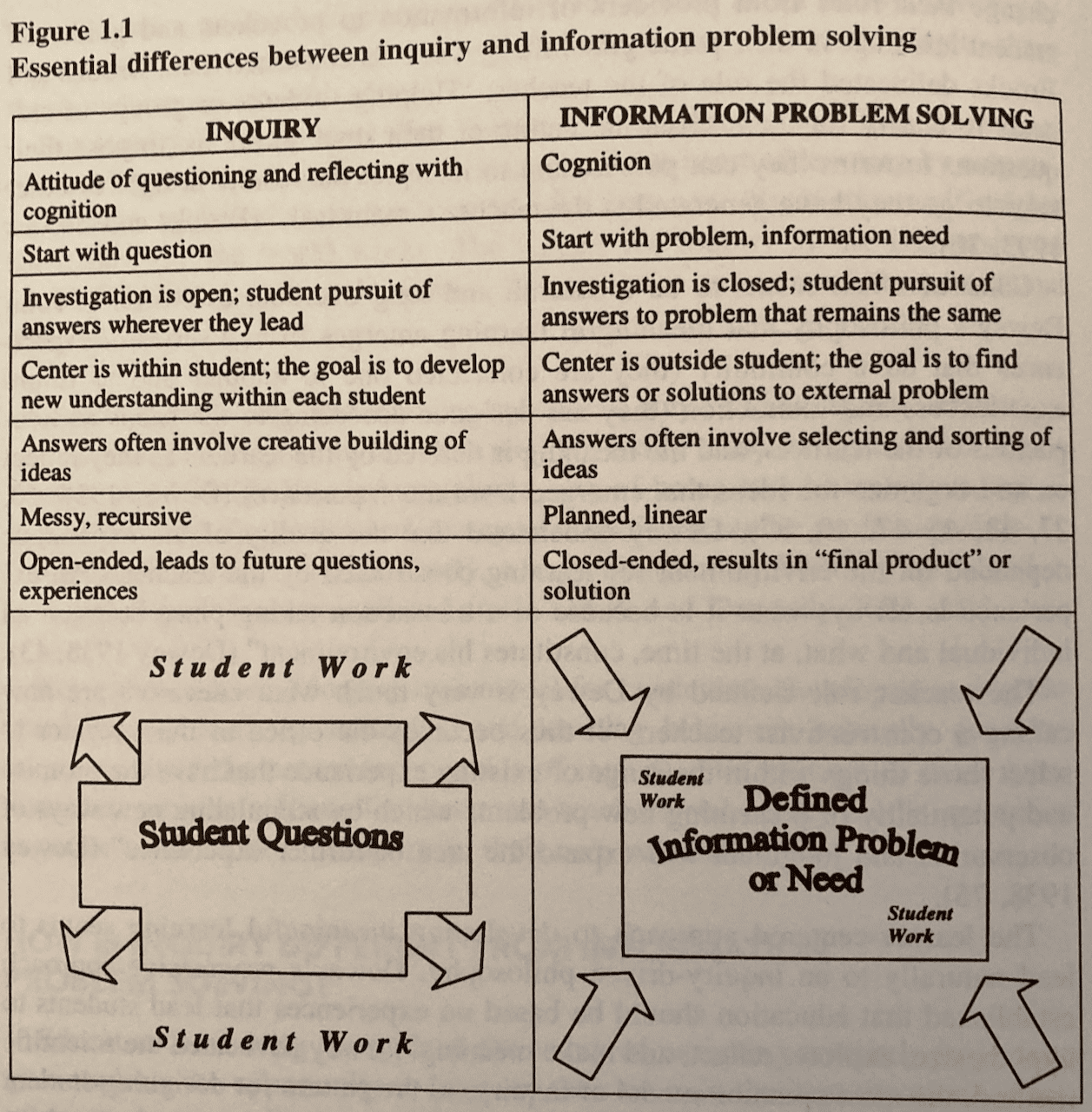

The choice of the Big6 as an example is an interesting, because it is an information problem solving process rather than an inquiry process – Barbara addressed this distinction in How is Inquiry Different From Information Problem Solving, in her chapter on Inquiry-Based Learning, in Curriculum Connections Through the Library (2003, pp. 4-6).

The differences are summarised in the following table (p. 6) – note that the starting question in inquiry is not the same as the final/ formal question that emerges from the investigation:

Also, like most/ all information problem solving/ research process models, it appears that the Big6 is no longer being actively developed and supported, and is/ was proprietary. This reflects the broader shift from research process models to inquiry process models – see, for example, the first (2002) and second (2015) editions of the IFLA School Library Guidelines – and means that it is unlikely that schools adopting it will be part of a vital, supportive community of inquiry/ practice.

References

- IBO. (2019). Ideal libraries: A guide for schools. Cardiff: International Baccalaureate Organisation.

- Stripling, B. K., & Hughes-Hassell, S. (Eds.). (2003). Curriculum Connections Through the Library. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Tilke, A. (2011). The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program and the School Library: Inquiry-Based Education. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

12th February 2025 at 1:36 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85738Endorsements received from Dr Luisa Marquardt, Professor at Roma Tre University | Department of Education and Chair of the School Libraries Section | IFLA

—

11th February 2025 at 3:01 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85528

11th February 2025 at 3:01 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85528I share the following for completeness of the proceedings, but please note that I am waiting for a minor adjustment to the stage colours, after which we will make the posters, stages and images available in Resources.

—

—

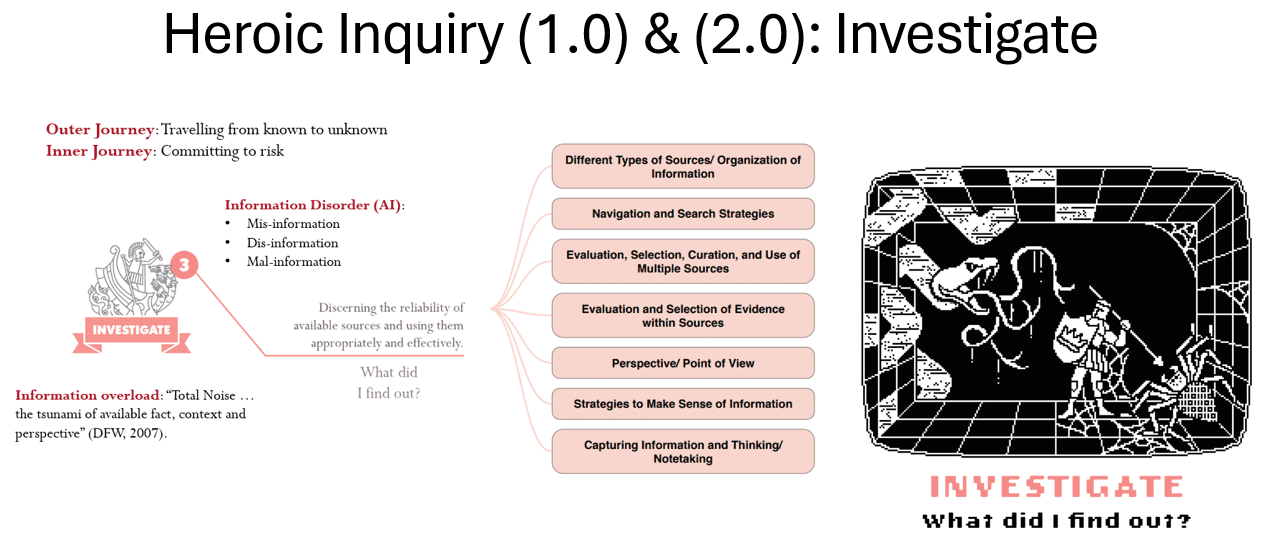

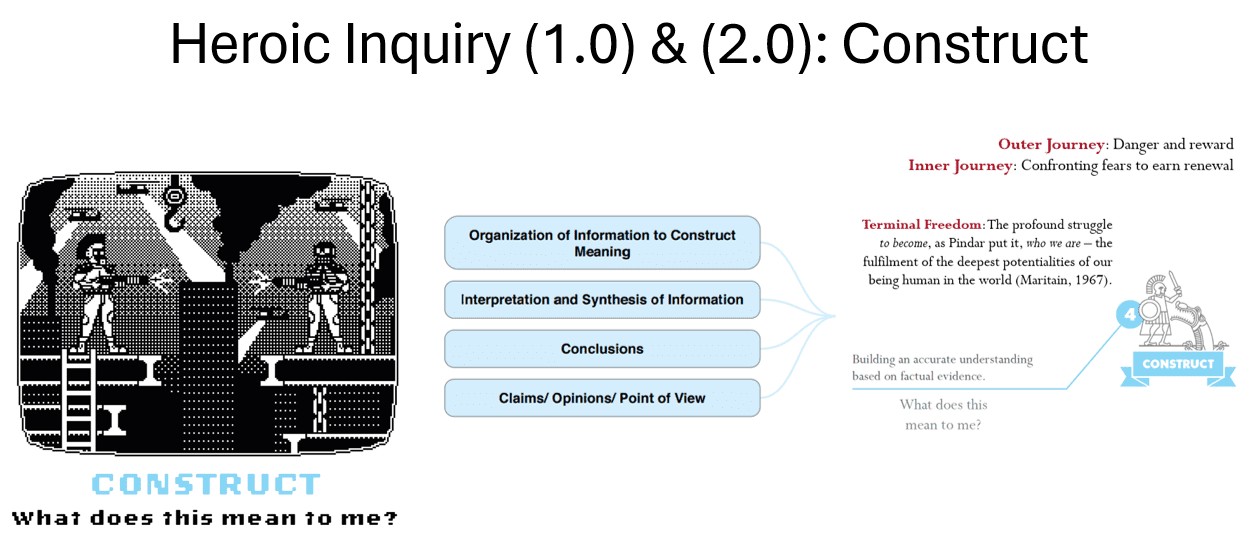

A reminder of of what is going on in Investigate and Construct.

11th February 2025 at 12:22 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85523

11th February 2025 at 12:22 pm in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85523The work with Hugh Rose on the Creative Commons (CC) reboot of Heroic Inquiry will require the most time to discuss, but I don’t want to delay making the link to proceedings live. Therefore, and for now, I will make the following observations:

- The ‘classical’ version of Heroic Inquiry (1.0) was produced in collaboration with Hugh Rose in 2021 while he was working at Blanchelande College under the previous Principal, whose influence on the images was strongly felt. This is appropriate, given the centuries-long educational tradition in Guernsey that Blanchelande is rooted in.

- Because this iconography is so closely associated with Blanchelande, opportunities to share our unfolding understanding of the embodiment of the inquiry stance and process in the Heroic Inquirer and through the Heroic Inquiry journey were constrained. Moreover, as the current Principal, Alexa Yeoman, noted in her address, being rooted in this rich tradition does not trap us in the past, given Blanchelande’s commitment to providing an outstanding contemporary liberal education, of which inquiry is a distinguishing feature. This forward-looking educational stance enables us to equip our students for their futures as engaged and empowered independent learners and active citizens, as our Director of Studies, Jane Grange, noted in her address.

- Growing interest in Heroic Inquiry, combined with a growing need to reconceptualise Heroic Inquiry in contemporary terms that spoke more directly to the reality our students need to deal with, created the conditions for the CC reboot of Heroic Inquiry in 2024-5.

- This posed a number of challenges, not least of which were that Hugh no longer worked at Blanchelande, I had a limited budget for FOSIL-related development and we had a very tight deadline if we were to share the CC reboot during the FOSIL Symposium. I am indebted to our then-Acting Principal, Mike Elward, who immediately saw the importance and value of this work, as well as freely sharing it under a CC licence, and to our Bursar, Mark Lewis, for approving an out-of-budget expense. My meetings with Hugh were limited to evenings and weekends, and many emails.

- This led to technical difficulties that will become apparent. In order to make the reboot as inclusive and diverse as possible within the constraints above, and without resorting to forced stereotypes, we decided to approach the Heroic Inquiry stages in the style of a video game (although there are also cinematic references), in which character creation and identification is natural. While we did not have time to investigate deeply, a cursory investigation confirmed that this combination of video game style with cinematic references appealed equally to boys and girls. The settings of the stages gave us further opportunities for inclusion and diversity. The pixelated style created exciting possibilities, but also imposed technical limitations that I do not fully understand – especially considering that we deliberately chose not to use colour (except for the stage names, which will print fine without) – but can appreciate.

- Additionally, we used the following for racial/ethnic reference, although this aspect was even more difficult to respectfully address: National Center for Education and Statistics, Definitions for New Race and Ethnicity Categories (2025).

- While we did not hold any formal consultations during the design process, we did not work in isolation, and sought and acted on feedback from a relatively diverse audience, which included both boys and girls of school-going age, and from different nationalities. Hugh shared the following thoughts with me following his presentation: “I encourage educators to look at this poster as a storytelling tool. It is up to them to tell the story and bring it alive for their students. The images have been carefully designed to allow the use of various pronouns and indeed cultural references. I hope everyone has fun creating their own epic stories with the framework we have created!“

- An unexpected budgetary difficulty that we ran into was that I had not accounted for the central Heroic Inquirer, so Jenny and are the proud ‘owners’ of this image!

We are proud to share the final design under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, and encourage colleagues to adopt or adapt as needed, and to share their experiences. I will reflect on the stages and images from my perspective in due course.

11th February 2025 at 11:12 am in reply to: Session 2b: Darryl Toerien & Hugh Rose (Heroic Inquiry) #85522Every inquiry, whether formal or informal, is a heroic journey.

Broadly, inquiry is a movement – intellectual,certainly, but also, and equally important, physical, emotional and social – from the comfort of the known into the discomfort of the unknown, there to wrestle knowledge from information and understanding from knowledge. There lurks real danger here, for being even somewhat misguided can lead far astray, and so discerning those who would help from those who would hinder, or even harm, is vital. From this now-enlightened place to return, enlivened and alive to possibilities heretofore unimagined. And so to set off again.

This heroic journey of inquiry is the story of those who have stretched the boundaries of human knowledge and understanding in one or more of the fields of study in which they laboured, and those who labour there still. It is this unfolding story that we are inviting our students to identify with and, in learning to stretch the boundaries of their own knowledge and understanding, add their voice to and so find their place in.

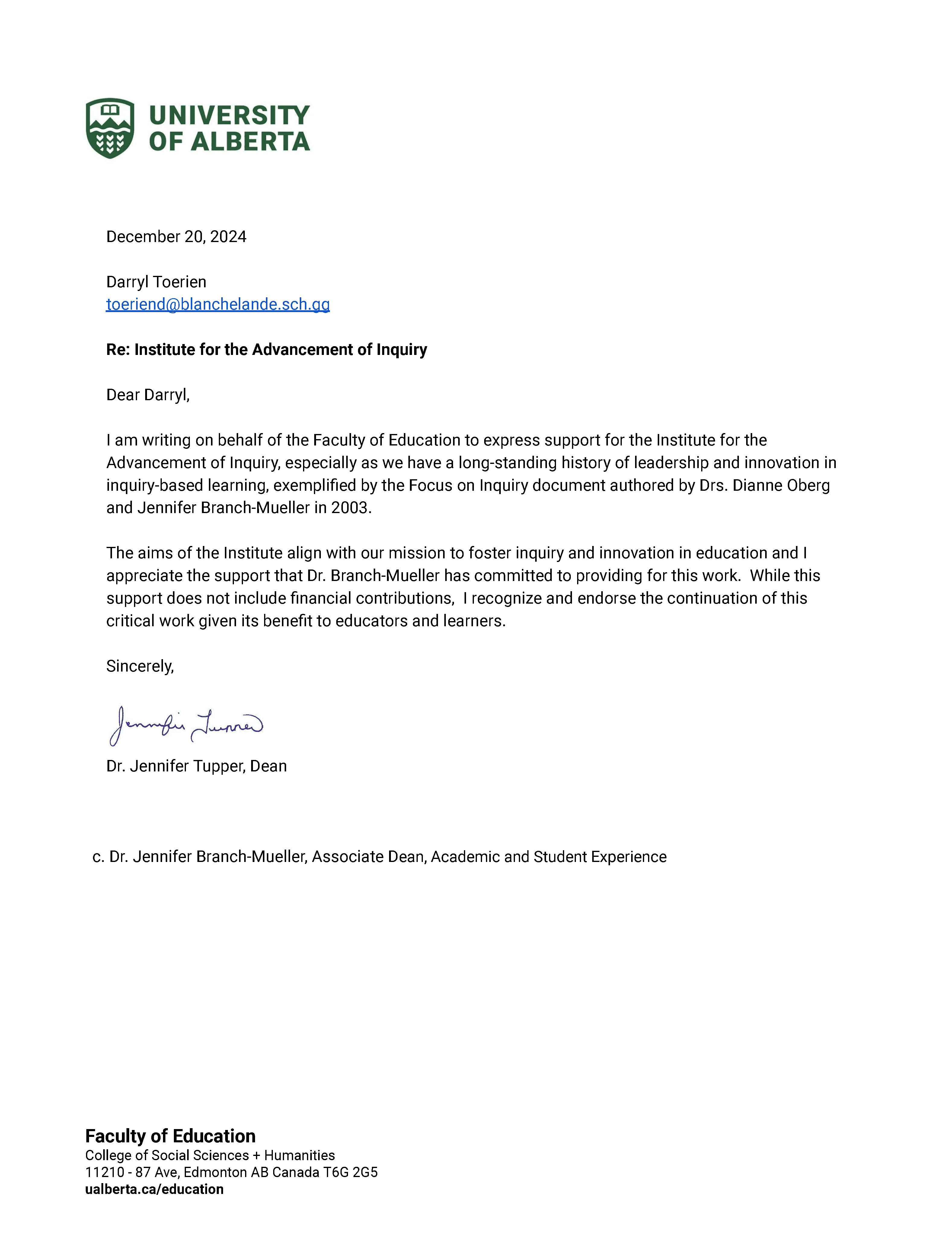

11th February 2025 at 10:00 am in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85521Endorsing the Institute

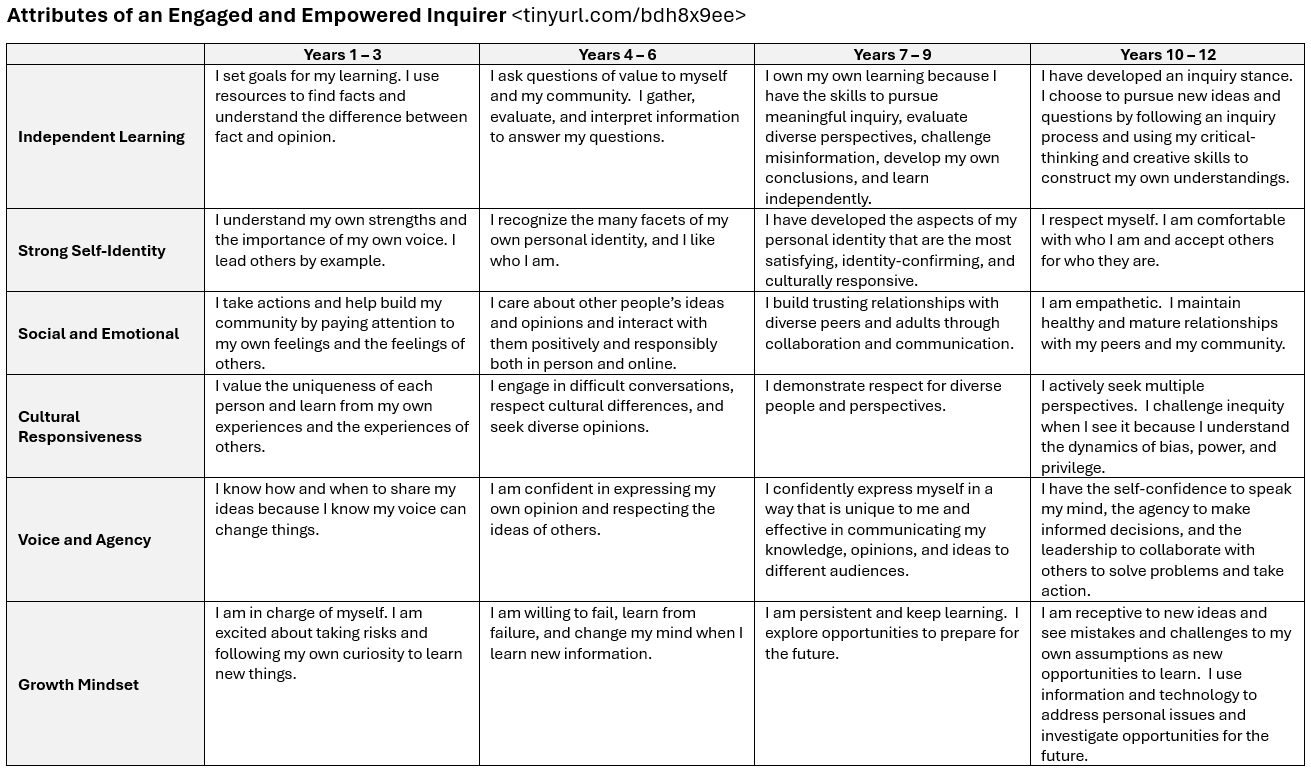

The foundation of the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry – the purpose of which is to initiate and support efforts, formal and informal, that foster the development of school-age children as engaged and empowered inquirers, which both enables them to fulfil the deepest potentialities of their being human in the world, and strengthens the liberal-democratic fabric of society – is clearly necessary and urgent.

This is evident from the extraordinary interest in and contribution to the FOSIL Symposium, which was not limited in focus to FOSIL.

It is also evident in the heartening endorsements of the Institute that I have already received, which I include below in chronological order.

—

Dr Barbara Stripling, Professor Emerita at Syracuse University | School of Information Studies first helped me to set this work in motion more than a year ago (23 January 2024):

I wholeheartedly support the establishment of an institute to support the school library field in developing inquiry-based libraries and schools. The reasons for creating a culture of inquiry in every school are numerous, but they all revolve around the essential core – the empowerment of young people to follow their own sense of wonder, navigate the world, and pursue their own paths of learning.

School librarians across the world are grappling with the complexities of transforming their libraries and schools into centers of inquiry. An online institute would provide open access to relevant research, practical strategies, success stories, adaptable models and frameworks, professional development, and a network of colleagues who are engaged in this important work. An online institute would also provide an incubator for new ideas and planning for the future.

I would be honored to collaborate with Darryl Toerien in developing and contributing to an inquiry institute.

Pending Endorsements

- Dr David Loertscher, Professor at San Jose State University | School of Information

- Dr Luisa Marquardt, Professor at Roma Tre University | Department of Education Science and Chair of the School Libraries Section | IFLA

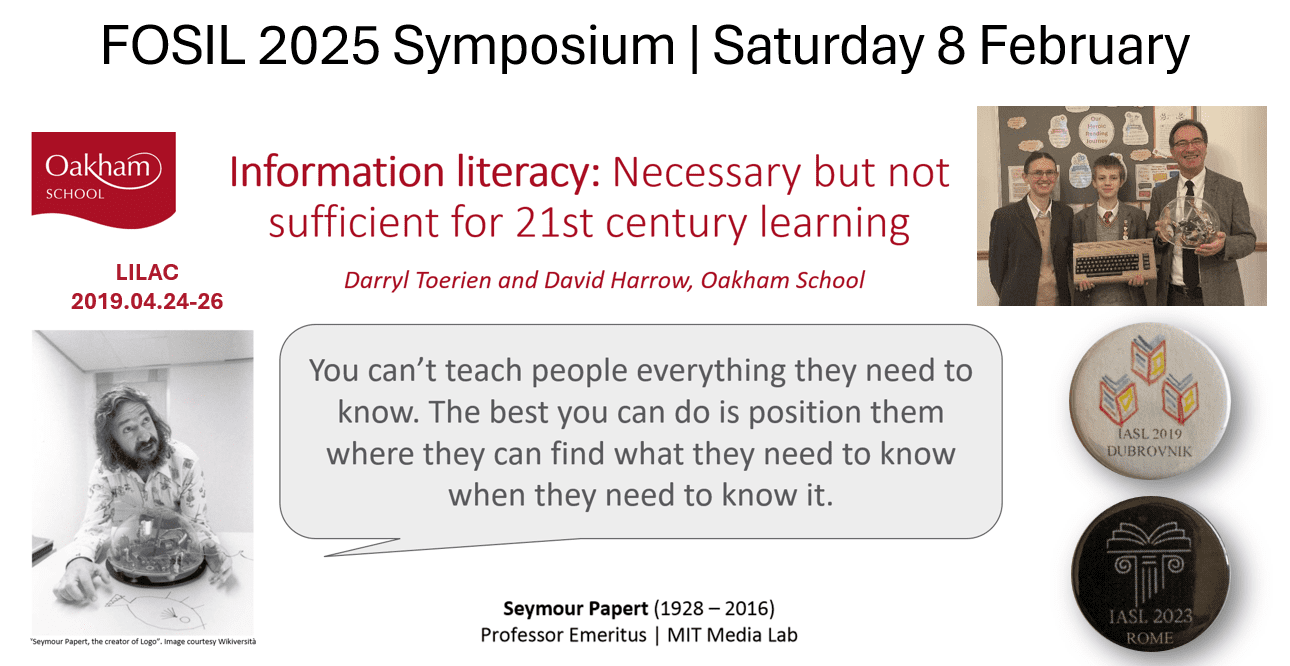

11th February 2025 at 8:05 am in reply to: Session 1a: Elizabeth Hutchinson & Darryl Toerien (Welcome) #85511Because of the structure of the day and time constraints, I did not share my full introductory remarks, which are, in fact, a welcome. I have, therefore, included them here in full, both for context and the record.

—

I have longed for this day since announcing the FOSIL Group in a presentation at LILAC 2019 and am overjoyed to be in such fine company – more than 200 colleagues from more 25 countries.

Apart from its historical significance, the title slide from this presentation encapsulates much, if not all, of what draws us together today. The picture of Jenny, Reuben and me – along with a genuine Edinburgh Turtle and Commodore 64 – is from this morning, because we have had the privilege of meeting many of you, and some of you have asked after Reuben, who is doing very well thank you, and who has grown quite tall for someone who still has 6 months to go until his 12th birthday.

So, while I could spend all of my time today drawing this significance out, I will highlight only the following:

- I was blessed to meet Seymour Papert, who profoundly influenced my understanding of how we learn, and in learning, the use of technology as tools to think with.

- I was blessed to discover a genuine Edinburgh Turtle, which was developed by the University of Edinburgh’s Artificial Intelligence Department to work with Seymour Papert’s Logo programming language, which is what the LEGO Mindstorms robotics platform was based on.

- I was blessed to grow up during the microcomputer revolution of the 1980s, which placed an extraordinarily powerful tool to think with in the hands of school-age children, hence my modest collection of 8- and 16-bit microcomputers. My most formative years at school were spent, therefore, in Computer User Group meetings, which embodied the hacker spirit at MIT, out of which the microcomputer revolution grew, and where Seymour Papert co-founded the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory with Marvin Minsky.

The culture of the various Computer User Groups was radically inclusive – all that was required to join one was an interest in computers, and joining one wasn’t even necessary to attend their meetings, which were free and open, and often held in school halls, where if you needed to learn something you found someone to teach you, and if you knew more than someone else you taught them. They were also, therefore, radically diverse, to the extent that it was possible in Apartheid South Africa, and contributed in some part to undermining that wicked regime.

This culture profoundly influenced me, and the hacker spirit – figuring things out for yourself with help from wherever you could find it, and sharing what you’ve learnt with whoever was interested, which is the spirit of inquiry – animated me, and this is how I approached the development of FOSIL and the FOSIL Group. More on this later.

Conventional wisdom has it that you shouldn’t start a communication with an apology – so, sorry for starting with an apology.

If what I say sounds scripted, that is because it is. The reason for this is that your time is precious, and the best way for me to honour your generous gift of time is for me to be as purposeful and deliberate as possible with what I say. Having said that, countless hours over many sleepless nights was not quite enough to finish things as I would have liked, so you will find me rough but ready in some places.

Thank you, then, for being here today, especially those in other time zones, whose sacrifice of time is greater than most, which means that it is accurate to say good morning, good afternoon and good evening to you. Thank you especially to those dear colleagues who are sharing with us today, and without whom we would not be here, and to Elizabeth for technically the same reason. We, and certainly I, would not be here without Jenny, who, as many of you will know, was an exceptional classroom teacher, but who, in my opinion, is an even more exceptional Teacher Librarian, and much of the foundational work on the FOSIL Group website that we still depend on was done by her. I would also like to thank the UK School Library Association, who have supported the work of the FOSIL Group through the FOSIL Group website since its foundation.

Perhaps most significantly for today, we would not be here except for a Principal of a school who understood that a fully human education required the library to be a unique kind of learning space, and the school librarian to be a unique kind of teacher. When I serendipitously wandered out of the classroom and into the library, Richard Blake and Jean Warwick created the conditions in which I could ask, and still continue to ask, what kind of learning space, and what kind of teacher? They created an enabling inquiry environment for me as an inquirer that continues to shape my work today, which is what I and we strive to do for students every day.

The earliest reference that I have to FOSIL is from 2010, which means that 2025 marks 15 years of thoughtful development of FOSIL, and since 2020 in weekly discussion with Barbara Stripling, whose work is foundational to FOSIL.

This brings me to the first major FOSIL development, which is the book that Barbara and I have been contracted to write for Bloomsbury Libraries Unlimited, titled, Teaching Inquiry as Conversation: Bringing Wonder to Life. This book, which we will finish by the end of August, enables us to draw our work together more closely, and to develop it more fully.

So, with the benefit of 15 years of hindsight, insight and foresight, what is FOSIL, bearing in mind that we understand inquiry to be a stance of wonder and puzzlement that leads to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it as the basis for responsible participation in community?

Firstly, FOSIL is an evolving response to the question, “What is school for?”

The answer to this question is neither as obvious nor as simple as it at first appears.

Jacques Maritain, who is proving to be especially helpful in this regard, considers that “the chief task of education is above all to … guide the evolving dynamism through which a person forms themself as a person” (1943/ 1971, p. 1), or, in other words, to enable our students to realise their full potential as human beings in relation to each other in the world.

This requires them to know and understand things about the world and themselves and each other, to be sure, but it also requires them to be able to come to know and understand those things, or, in other words, to know how to acquire knowledge and understanding of those things, and many more besides. This is more than mere memorisation and reproduction.

Secondly, then, FOSIL is an evolving response to the question, “How does school enable this human awakening in a coherent way?”

For Maritain, “education is fully human education only when it is a [contemporary] liberal education, preparing the youth to exercise their power to think in a genuinely free and liberating manner — that is to say, when it equips them for truth and makes them capable of judging according to the worth of evidence, of enjoying truth and beauty for their own sake, and of advancing, when they have become adults, toward wisdom and some understanding of those things which bring to them intimations of immortality” (1962/ 1967, pp. 47-48).

A distinguishing feature of a contemporary liberal education is inquiry, especially in the form of Signature Work (AAC&U, 2020), which is a learning stance and process, encapsulated by C.S. Peirce (1955) in his first, and in one sense only, rule of reason: “In order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so doing not be satisfied with what you already incline to think” (p. 4).

Inquiry, then, in forms appropriate to its subject matter, is responsible for what we know and understand about the world as reflected in the various disciplinary bodies of knowledge that cohere into a meaningful and interdisciplinary whole. This is why inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning matters, because inquiry is fundamentally how we come to know and understand the world and ourselves in it – reality – which is the basis for responsible participation in community, and which is ultimately the only true measure of human success.

Consequently, as Maritain (1952, p. 3) puts it: “Nothing is more important than the events which occur within that invisible universe which is the mind of [a person]. And the light of that universe is knowledge. If we are concerned with the future of civilization we must be concerned primarily with a genuine understanding of what knowledge is, its value, its degrees, and how it can foster the inner unity of the human being.”

Viewing and approaching the acquisition of knowledge in this way, and to this end, requires purposeful and effectual collaboration between classroom-based teachers and library-based teachers. The library is, after all, as Douglas Knight (1968) reflected, a uniquely creative meeting place for minds and ideas, and then the active extension of those ideas in the minds of our students, which depends for this essential function on the vital collaboration between those who teach the mind to inquire and those who teach the mind how to inquire (pp. vi-ix).

Thirdly, then, FOSIL is an evolving community of inquiry formed in response to the question, “What, in my specific educational context, does inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning look like?” My response to the question – FOSIL – led eventually to the formation of the FOSIL Group in 2019, which is a shared approach to this educational imperative, and is what brings us together today. The response to this question, however, is broader than FOSIL. I have already mentioned my debt to Barbara, whose Empire State Information Fluency Continuum is distinct from FOSIL, even though they have essential features in common, and who brings today’s proceedings to a close. I am equally delighted that Dianne and Jennifer opened proceedings today, because their deeply thoughtful and highly influential Alberta Model of Inquiry, which is central to Focus on Inquiry: A Teacher’s Guide to Implementing Inquiry-based Learning was formative for me and is indicative of the FOSIL Group’s broader concern with inquiry (see Focus on Inquiry in the FOSIL Group Forum, and also E&L Memo 2 | Focus on Inquiry: Reflections on Developing a Model of Inquiry by Dianne). It is worth noting that Stripling’s Model of Inquiry (2003), which is central to the Empire State Information Fluency Continuum, FOSIL (2010), and the Alberta Inquiry Model (2004) account for three of the five models included in the IFLA / De Gruyter book, Global Action for School Libraries: Models of Inquiry (2022).

This brings me to the second major FOSIL development, which is the foundation of the [school-based] Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry [in PK-12 education].

Jonathan Rauch, in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (2021), highlights how our existential crisis is epistemological in nature – a breakdown in the knowledge-building process, which is the inquiry process. The Constitution of Knowledge – liberal democracy’s “epistemic operating system: our social rules for turning disagreement into knowledge” – depends on the vitality of a “reality-based community of error-seeking inquirers” (p. 15). This community has been severely weakened by the almost total failure of schools to equip students for their role in strengthening this community, a failure to enable inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning in PK-12 education. And it is precisely because school “is the one institution in our society that is inflicted on [almost] everybody,” that Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner (1969/ 1971) forewarned that “what happens in school makes a difference – for good or ill” (p. 12).

As today demonstrates, concern with these questions, and responses worthy of our serious consideration, is broader than FOSIL. This is healthy, and is the rationale for the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry, which is to support and provoke thoughtful effort to enable inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning in PK-12 education regardless of model, and this for the purpose of developing a reality-based community of engaged and empowered inquirers.

This brings me to the third major FOSIL development, which is the Creative Commons reconceptualization of the Heroic Inquiry Cycle for a contemporary liberal education, which I first developed with Hugh Rose at Blanchelande College in 2021. Hugh and I will share this later.

10th February 2025 at 2:54 pm in reply to: Session 2a: Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry (Blanchelande College) #85486Founding the Institute by Darryl Toerien

This brings me to the second major FOSIL development, which is the foundation of the [school-based] Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry [in PK-12 education].

Jonathan Rauch, in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (2021), highlights how our existential crisis is epistemological in nature – a breakdown in the knowledge-building process, which is the inquiry process. The Constitution of Knowledge – liberal democracy’s “epistemic operating system: our social rules for turning disagreement into knowledge” – depends on the vitality of a “reality-based community of error-seeking inquirers” (p. 15). This community has been severely weakened by the almost total failure of schools to equip students for their role in strengthening this community, a failure to enable inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning in PK-12 education. And it is precisely because school “is the one institution in our society that is inflicted on [almost] everybody,” that Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner (1969/ 1971) forewarned that “what happens in school makes a difference – for good or ill” (p. 12).

As today demonstrates, concern with these questions, and responses worthy of our serious consideration, is broader than FOSIL. This is healthy, and is the rationale for the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry, which is to support and provoke thoughtful effort to enable inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning in PK-12 education regardless of model, and this for the purpose of developing a reality-based community of engaged and empowered inquirers.

The Institute has been incorporated in these terms:

The purpose of the Institute is to initiate and support efforts, formal and informal, that foster the development of school-age children as engaged and empowered inquirers. This both enables them to fulfil the deepest potentialities of their being human in the world, and strengthens the liberal-democratic fabric of society.

To this end, the Institute will collaborate with partners who are aligned with its purpose, both in terms of research into and development of inquiry as a method of instruction and an environment for formalised learning, and in terms of funding. The Institute will provide a public service to educators that is free at the point of need, but it is anticipated that additional funding will come from consultancy engagements and standalone training events.

The Institute has been established with the assistance of Mark Le Page, who is joined on the Board by Barbara Stripling, Dianne Oberg and Luisa Marquardt, Professor at Roma Tre University and Chair of the IFLA School Libraries Section.

—

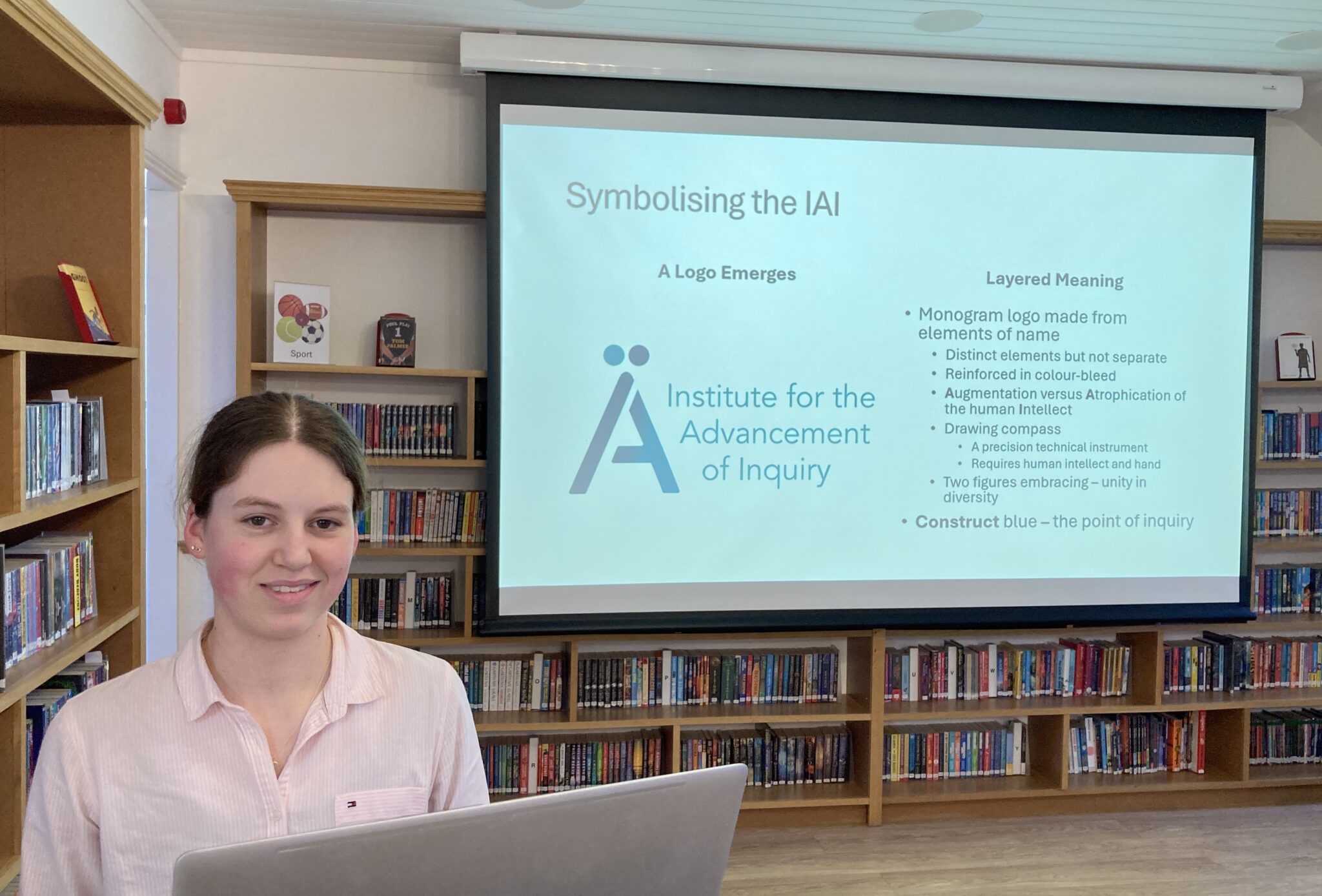

Symbolizing the Institute by Lara Stanford (Year 13 / Grade 12 Student at Blanchelande College)

Please note that there are two minor adjustments to the logo that need to be before it is finalized.

Within the broader context of the relationship between humans and their machines, each letter in this monogram logo – the IAI – is distinct, but not separate, reflecting the fact that inquiry cannot be meaningfully separated from digital age tools within a digital environment.

This dynamic relationship is reinforced with the colour gradient between the letters.

It therefore also reflects the tension between augmenting human intelligence and the atrophication of human intellect through the misuse of digital-age tools, such as Artificial Intelligence, threatening to replace the need for inquiry and learning altogether.

It can also be interpreted as two figures embracing.

This reflects the principle of ‘unity in diversity’, an ancient phrase expressing harmony and unity between individuals. This relates to the Institute as it aims to be a forum for collaboration and sharing different ideas amongst educators of all kinds, with the shared intent to advance inquiry for students and their ability to pursue learning on their own, using a wide range of digital-age tools to augment human intelligence rather than to diminish it.

After designing the logo and reflecting on it, we discovered that the shape of this logo could also signify a drawing compass, which is a precision instrument for technical use, requiring both human mind and body. This seems fitting because it illustrates the purposeful use of human tools to serve human ends.

Finally, on our choice of colour. Blue has significant symbolism as it represents a critical stage of the FOSIL inquiry cycle – the Construct stage. This is where knowledge is transformed into understanding, and students develop their own ideas based on their investigation and the evidence they have found. It seemed fitting, therefore, that Construct blue would be the colour for the face of the institute, knowing that, as Jacques Maritain stated, “nothing is more important than the events which occur within that invisible universe which is the mind of [a person], the light of which is knowledge.”

—

Integrating the Institute by Jane Grange

Here at Blanchelande College, inquiry is not just a teaching method—it’s a culture. By integrating the work of the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry, we aim to create a reality-based community of engaged and empowered learners. As Darryl has noted, this requires purposeful collaboration between classroom teachers and library-based educators, ensuring inquiry is embedded throughout the curriculum.

A key feature of integrating inquiry into our practical approach is Signature Work—structured inquiry projects that equip students with essential skills at key developmental stages. Our youngest learners in Years 1 and 2 begin with inquiries such as Why visit Guernsey? and Who lives on Herm?, fostering curiosity and community engagement. By Year 6, students undertake an interdisciplinary inquiry, which spans Theology, Science, English, Art, Maths, and ICT, earning them a CREST Bronze Award and empowering them to campaign for causes they care about. Last year, they raised over £570 and even inspired the Lieutenant Governor to plant a tree at our school. This year, we’re strengthening these community connections by inviting local charities to engage directly with students.

In the upper years, inquiry deepens. Year 9’s Signature Work, now a timetabled subject, develops speaking and research skills for their GCSE English assessment, while Year 12’s Interrobang!? project introduces them to AI and inquiry-based learning, often leading to the Extended Project Qualification (EPQ). These qualifications challenge students across all abilities—whether they are researching humanitarian issues in Syria or designing a drone.

Beyond set projects, inquiry is being embedded across subjects—Maths, Geography, English, Business Studies, and beyond—while our new Scholars’ Society provides the most able students with an inquiry approach to externally-focused opportunities, including national competitions and the TeenTech Awards.

Through these initiatives, we are not only advancing inquiry learning but fostering critical thinking, creativity, and community engagement—empowering students to become independent learners and active citizens. We look forward to the further collaborative opportunities and outward looking inquiries that the Institute will bring.

—

Hosting the Institute by Alexa Yeoman

Blanchelande College has educational roots in Guernsey that reach back to the 1100s. This centuries-long commitment to enabling children to realise their full potential as human beings is reflected in our Mission and our Aims. Drawing nourishment from this rich tradition does not trap us in the past. Rather, an education in this tradition has as its end students who can think in a genuinely free and liberating manner, using the full range of tools at their disposal, which is the hallmark of a contemporary liberal education at Blanchelande.

In FOSIL, we have we have a powerful tool for developing engaged and empowered inquirers, students who are willing and increasingly able to learn for themselves, which is the surest way to equip them for their future.

In the FOSIL Group we belong to a growing international community of exceptionally dedicated and thoughtful educators who are using FOSIL to engage and empower students as inquirers, as today clearly demonstrates, and we are proud to play a central role in this.

In the Institute for the Advancement of Inquiry, we recognise the outstanding efforts of a wider, international community of engaged and empowered inquirers, and are honoured to be able to facilitate this collaborative work.

—

Valuing the Institute by Mark Le Page

Mark referenced a BBC interview with Bertand Russell, which is developed more fully below.

In April of 1959 the British philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell sat down with John Freeman of the BBC program Face to Face for a brief but wide-ranging and candid interview. … In answering the question [of what message he would offer to people living a thousand years hence], Russell balances the two great spheres that occupied his life.

“I should like to say two things, one intellectual and one moral:

The intellectual thing I should want to say to them is this: When you are studying any matter or considering any philosophy, ask yourself only what are the facts and what is the truth that the facts bear out. Never let yourself be diverted either by what you wish to believe or by what you think would have beneficent social effects if it were believed, but look only and solely at what are the facts. That is the intellectual thing that I should wish to say.

{This is the intellectual dimension of inquiry, and pertains to the first part of our definition of inquiry as “a stance of wonder and puzzlement that gives rise to a dynamic process of coming to know and understand the world and ourselves in it….“}

The moral thing I should wish to say to them is very simple. I should say: Love is wise, hatred is foolish. In this world, which is getting more and more closely interconnected, we have to learn to tolerate each other. We have to learn to put up with the fact that some people say things that we don’t like. We can only live together in that way, and if we are to live together and not die together we must learn a kind of charity and a kind of tolerance which is absolutely vital to the continuation of human life on this planet.”

{This is the moral dimension of inquiry, which is the outworking of the intellectual dimension, in that knowledge and understanding of things as they actually are – reality – is necessary if we are to deal with things as they actually are, which is the only true measure of success, and pertains to the second part of our definition of inquiry: “…as the basis of responsible participation in community.”}

These two things lead to the third, which is the international nature of the Institute, which makes Guernsey ideal as its base.

-

AuthorPosts